Abstract

Diverse preconditioning (PC) stimuli protect against a wide variety of neuronal insults in animal models, engendering enthusiasm that PC could be used to protect the brain clinically. Candidate clinical applications include cardiac and vascular surgery, after subarachnoid hemorrhage, and prior to conditions in which acute neuronal injury is anticipated. However, disappointments in clinical validation of multiple neuroprotectants suggest potential problems translating animal data into successful human therapies. Thus, despite strong promise of preclinical PC studies, caution should be maintained in translating these findings into clinical applications. The Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) working group and the National institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS) proposed working guidelines to improve the utility of preclinical studies that form the foundation of therapies for neurological disease. Here, we review the applicability of these consensus criteria to preconditioning studies and discuss additional considerations for PC studies. We propose that special attention should be paid to several areas, including 1) safety and dosage of PC treatments; 2) meticulously matching preclinical modeling to the human condition to be tested; and 3) timing of both the initiation and discontinuation of the PC stimulus relative to injury ictus.

Keywords: translational research, preconditioning, ischemic tolerance, STAIR, remote ischemic preconditioning

Introduction

First described in heart (Murry, Jennings et al. 1986), preconditioning (PC) describes a phenomenon whereby a stimulus upregulates mechanisms in a tissue that protect against a subsequent more severe injury. Thus, in brain, prior exposure to a short duration of ischemia protects against a longer duration of ischemia, so-called ischemic PC (Obrenovitch 2008; Fairbanks and Brambrink 2010; Keep, Wang et al. 2010). This effect can be also be induced pharmacologically by a wide range of agents, so-called pharmacological PC (Obrenovitch 2008; Dirnagl, Becker et al. 2009; Gidday 2010). The original heart studies showed biphasic protection with an effect soon after the PC stimulus (classical or early PC) and an effect that takes hours to develop (delayed PC) relying on new protein production. In animal models of transient or permanent cerebral ischemia, the protective effects of delayed PC are marked. The early protective effects of PC are more variable, but have been shown in multiple studies (Obrenovitch 2008; Keep, Wang et al. 2010).

The marked protective effects of PC have led to debate about how to translate these findings to the clinic. Three major issues have arisen in such discussions. 1) Safety. PC stimuli generally, if not always, act as a stressor to induce the protective response. This raises issues as to whether these can safely be given (and titrated) in patients. 2) Which neurological condition should PC be examined in? As the PC stimulus is given before the injury, there is a need to know when an injurious event will or might occur. 3) Multiple neuroprotectants have failed in clinical trial suggesting that either there are deficiencies in the animal stroke modeling or that there are problems with how the preclinical data is translated to the clinic. There is, therefore, a desire to learn from those failures in relation to any PC trial, particularly as failure of a PC clinical trial could significantly impact this promising line of investigation. This third point is the main focus of this paper. It should be noted that there are similar concerns in the cardiac literature where there have been many preclinical studies showing the efficacy of PC, but these have not translated to the clinic (Ludman, Yellon et al. 2010).

This discussion is particularly pertinent now because of the finding that transient ischemia in a distant tissue can induce PC in brain and other tissues, so-called remote ischemic preconditioning (RIPC; (Hausenloy and Yellon 2008; Kharbanda, Nielsen et al. 2009; Fairbanks and Brambrink 2010)). Thus, for example, periods of limb ischemia protect against cerebral ischemia (Dave, Saul et al. 2006; Ren, Gao et al. 2008; Jensen, Loukogeorgakis et al. 2011; Malhotra, Naggar et al. 2011). This potentially greatly reduces PC-related safety concerns and has led to two pilot clinical studies examining RIPC in relation to the delayed cerebral ischemia that occurs in subarachnoid hemorrhage (NCT01158508; NCT01110239; (Koch, Katsnelson et al. 2011; Bilgin-Freiert, Dusick et al. 2012)).

Neuroprotection and the STAIR/RIGOR criteria

A discussion of clinical application of PC of the brain requires some reflection on the vast experience gleaned from trials of neuroprotectants for treatment of ischemic stroke. Neuroprotection against ischemic stroke has occupied the front line of basic and clinical efforts over the last several decades. Basic scientific advances have highlighted the potential of using pharmaceutical and biological agents to reduce ischemic brain damage. Because of impressive preclinical results, many neuroprotective strategies have undergone clinical trial.

At least 1026 neuroprotective stategies have been studied in preclinical work. In total, over 120 clinical trials of neuroprotectants for ischemic stroke have been conducted using an impressively diverse array of treatments. Notwithstanding laboratory successes, none of these lines of investigation have resulted in approved stroke treatments (extensively documented in multiple reviews including (Ginsberg 2008; Green 2008; Tymianski 2010; Sutherland, Minnerup et al. 2012)). The lack of translational success in ischemic stroke prompted several thought leaders in the field to create in 1999 a set of guidelines that could be used to help select from the impressive number of promising preclinical agents that could be taken into clinical trials (1999).

These guidelines, written by the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) working group, included the recommendations that preclinical stroke research determine: 1) Dose response curves. 2) Therapeutic time windows in good animal models. 3) Outcomes from blinded, physiologically controlled studies. 4) Both histology and functional outcomes. 5) Responses in gyrencephalic species. 6) Treatment effects in both transient and permanent occlusion stroke models.

The potential importance of these guidelines has been suggesting in several retrospective analyses. For example, a systematic review of over a thousand stroke experiments revealed poor overall adherence to STAIR principles (O'Collins, Macleod et al. 2006). Moreover, in an update to the original STAIR statement (Fisher, Feuerstein et al. 2009), the committee noted that there was a significant trend that increased apparent efficacy of the same drug was found in studies that did not adhere to STAIR criteria, particularly in blinding of outcomes and randomization. A marked inverse correlation between adherence to quality metrics of preclinical testing and effect sizes have been observed for a number of neuroprotective strategies (Macleod, O'Collins et al. 2005; van der Worp, Sena et al. 2007; Crossley, Sena et al. 2008; Macleod, van der Worp et al. 2008). As such, it has been proposed that the failure of clinical trials of neuroprotectants may be due to overestimates of effect sizes in suboptimal preclinical experiments.

Further improvements to the STAIR criteria have been discussed (Feuerstein, Zaleska et al. 2008) and in 2009 (Fisher, Feuerstein et al. 2009), the STAIR committee updated their recommendations to include: 1) Emphasis on randomization and reporting of exclusion of animals in studies, power calculations, better blinding of studies. 2) Inclusion of animals with comorbidities similar to aging human stroke patients (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia). 3) Inclusion of male and female animals and consideration of interactions between treatments and common medications. 4) Establishment of biomarkers that can be obtained in human trials to indicate that specific therapeutic targets have indeed been modified.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS) has also recognized a disconnect between preclinical data and clinical trial success and has recently proposed guidelines for evaluating preclinical data. These guidelines, sometimes referred to as RIGOR (DOI 10.1007/s12975-012-0209-2), are meant to improve the quality of preclinical studies to increase likelihood of success of similar studies in humans and are meant to reflect similar summary recommendations from the clinical research community (Schulz, Altman et al. 2010). Peer reviewers that advise NINDS on funding decisions for preclinical study support have been encouraged to consider the following recommendations: 1) Strict attention to model selection, endpoints, controls, and route, timing, and dosing of interventions with rigorous sample size and power calculations using explicit statistical methods for analysis; 2) Minimization of bias by blinding, randomization, reporting of excluded data; 3) Independent validation of results, dose response reporting, and verification that intervention reached and engaged the target; 4) Adequate discussion of alternative interpretations, relevant literature review, estimate of clinical effect, and potential conflicts of interest.

An important addition of the RIGOR statement is that both positive and negative data for a therapeutic modality should be reported; this would certainly allow more rational choice of the best therapeutic candidates, assuming that publication bias is adequately avoided in a universal fashion. Significantly, for investigators, this statement signals that a major federal funding agency that has supported preclinical neuroprotection studies is explicitly encouraging adherence to STAIR-like criteria for funding decisions.

Both the STAIR criteria and the NINDS RIGOR recommendations are rational guidelines for prioritizing preclinical targets for ischemic stroke trials. But these criteria have yet to make a recognizable impact on clinical translation or trials. In fact, the clinical trials that followed preclinical work that has most faithfully adhered to the STAIR criteria did not fulfill the promise of experimental models (including the negative phase III NXY-059 trial (Savitz 2007)). This indicates that additional criteria may be needed for optimizing preclinical testing before clinical trials are performed for an intervention.

Conversely, it may be argued that every STAIR and RIGOR recommendation may not apply directly to PC. For example, in RIPC, ischemic stress to the limb experimentally protects the brain from stroke. At least in animals, the intervention that shows benefit fails to reach and engage the target organ. The RIGOR criteria, in this case, would discourage the use of drugs that indirectly affect the brain or act on circulating cells and peripheral organs that secrete circulating substances that provide endogenous benefit. Similarly, there are potential PC clinical targets whose pathophysiology is not driven exclusively by ischemia (see below). For those, clearly, the stroke-specific components of the STAIR criteria (e.g. use of transient and permanent ischemia models) will not apply.

Where are we in PC preclinical testing?

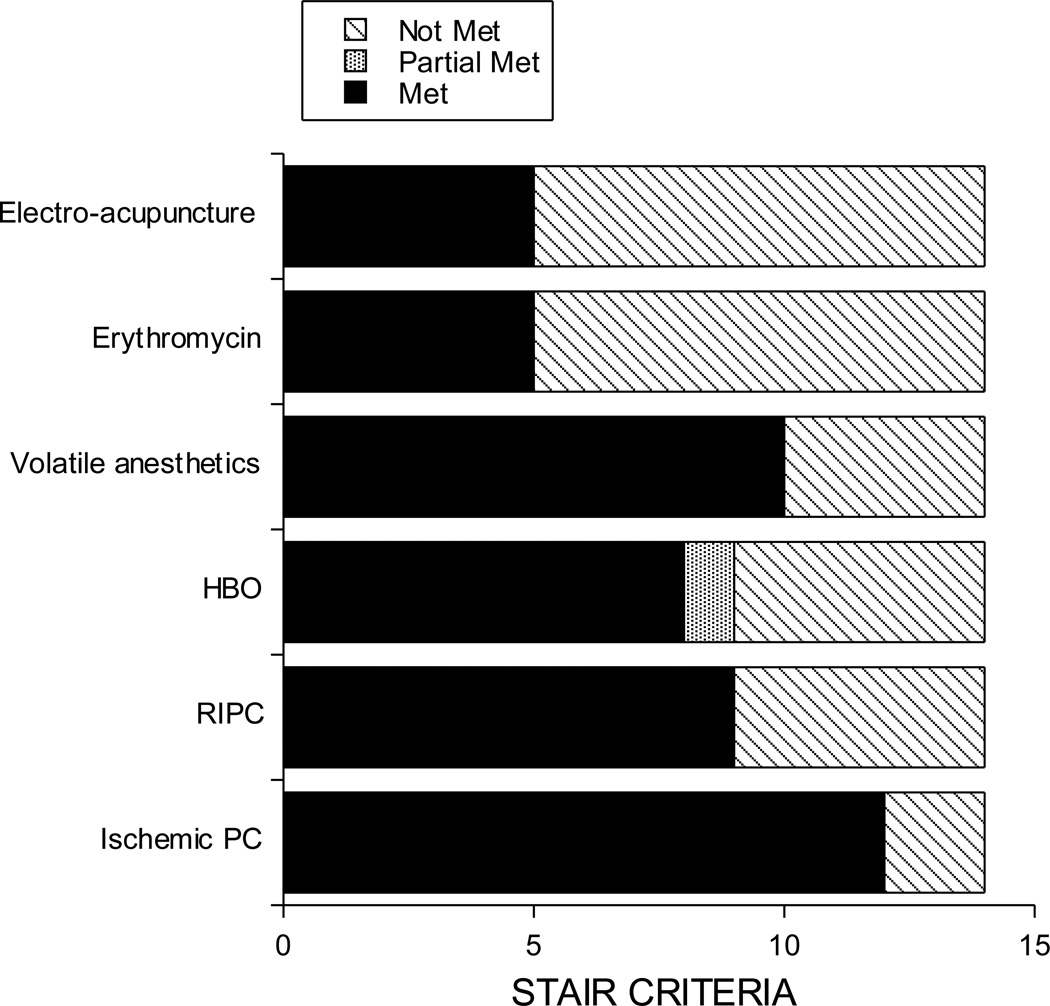

Although there is a mass of preclinical data supporting the effectiveness of PC stimuli in reducing ischemic brain damage, the extent of that data and potential deficiencies (with respect to STAIR criteria) varies with particular stimuli. For PC stimuli that are currently in clinical trials, many, but not all of the STAIR criteria have been tested in preclinical models of disease (Table 1). The criteria that have been addressed well include time window determination, histological/functional outcome assessment, and blinding, and randomization. Other criteria, such as examination of PC effects in aged or hypertensive animals, have only been addressed for a small number of PC stimuli. Overall, satisfaction of the STAIR criteria for protection in ischemic stroke models ranges from 36 to 86%, depending on the stimulus (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Pre-clinical data on different forms of preconditioning in relation to STAIR criteria

| Ischemic PC | RIPC | HBO | Volatile anesthetics |

Erythromycin | Electro-acupuncture | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | (Kirino, Nakagomi et al. 1996; Gidday 2006; Steiger and Hanggi 2007; Obrenovitch 2008; Dirnagl, Becker et al. 2009; Keep, Wang et al. 2010) | (Dave, Saul et al. 2006; Ren, Gao et al. 2008; Saxena, Bala et al. 2009; Hahn, Manlhiot et al. 2011; Jensen, Loukogeorgakis et al. 2011; Xu, Gong et al. 2011) | (Miljkovic-Lolic, Silbergleit et al. 2003; Matchett, Martin et al. 2009; Yamashita, Hirata et al. 2009; Keep, Wang et al. 2010; Cheng, Ostrowski et al. 2011) | (Nasu, Yokoo et al. 2006; Wang, Traystman et al. 2008; Li and Zuo 2009; Keep, Wang et al. 2010; Yung, Wei et al. 2012) | (Brambrink, Koerner et al. 2006; Koerner, Gatting et al. 2007) | (Xiong, Lu et al. 2003; Wang, Xiong et al. 2005; Wang, Peng et al. 2009; Wang, Li et al. 2011; Wang, Wang et al. 2012) |

| Dosing | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Time window | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Histology + function | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Both genders | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Multiple species (incl. gyrencephalic species) |

Rat, mouse, gerbil, rabbit (yes) |

Rat, pig (yes) |

Mouse, rat, gerbil (no) |

Mouse, rat dog (yes) |

Rat (no) |

Rat (no) |

| Aging | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hypertension | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Diabetes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hyperlipidemia | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Permanent ischemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Transient ischemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Multiple laboratories | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Blinding | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Randomization | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The extent to which pre-clinical testing of different preconditioning (PC) stimuli meets the STAIR criteria for treatment of ischemic stroke. It should be noted that for remote ischemic PC (RIPC), there have been far more studies examining protection of tissues other than brain. This Table is limited to PC stimuli that have been or are being studied in humans. The list of references gives examples or reviews of studies on a particular form of PC. For the notes on blinding/randomization, a ‘yes’ indicates that some studies have met those criteria. Some PC studies do not mention whether studies were performed on randomized animals or whether measurements were made by blinded observers. HBO = hyperbaric oxygen.

Figure 1.

The extent to which pre-clinical testing of different PC stimuli meets the STAIR criteria. It should be noted that for remote ischemic PC (RIPC), there have been far more studies examining protection of tissues other than brain. This figure is limited to PC stimuli that have been or are being studied in humans.

Three examples are given below of stimuli that have or are being examined in the clinic. It should be noted that while it may be possible to translate data from one form of PC to another, that is no means certain, e.g. if one form of PC is effective in a large gyrencephalic species, does that mean all forms of PC will be effective?

Direct ischemic PC (where the target tissue is made transiently ischemic) is the most widely studied PC stimulus (Gidday 2006; Obrenovitch 2008; Fairbanks and Brambrink 2010; Keep, Wang et al. 2010). It has been studied in different models of cerebral ischemia (permanent and transient; Keep, 2010 #48}) using different endpoints (behavior and histology). Effectiveness has been demonstrated by multiple groups in multiple species, although there is little data on gyrencephalic species (Keep, Wang et al. 2010). Yeh et al. reported ischemic PC in the gyrencephalic rabbit (Yeh, Wang et al. 2004) and Ara et al. reported hypoxic PC in the pig (Ara, Fekete et al. 2011). Although most studies have examined males, there is evidence for ischemic PC in female animals (Dowden and Corbett 1999; Abe and Nowak 2004). There has been a considerable amount of work done on the duration of ischemia (with or without repetition) required to induce PC and the time course of that induction (e.g.(Chen, Graham et al. 1996)), although there may be some difficulties in directly translating that data to humans (see below). One concern raised by the preclinical efficacy studies is that there is some evidence that stroke co-morbidities, hypertension and aging, can impact the effectiveness of ischemic PC (Purcell, Lenhard et al. 2003; He, Crook et al. 2005; Schaller 2007).

However, how to induce direct ischemic PC safely and minimally invasively remains the major concern of using this approach clinically. This has led to considerable interest in the use of RIPC. However, there have been far fewer preclinical studies and these have been predominantly in rat. They have shown RIPC protection against global (Dave, Saul et al. 2006; Saxena, Bala et al. 2009; Xu, Gong et al. 2011) and focal cerebral ischemia (Ren, Gao et al. 2008; Malhotra, Naggar et al. 2011; Wei, Ren et al. 2012). There have, though, been studies showing protection against global ischemia in mouse (Rehni, Shri et al. 2007) and pig (Jensen, Loukogeorgakis et al. 2011). Groups have shown both histological and neurological protection (Malhotra, Naggar et al. 2011; Wei, Ren et al. 2012). The parameters to induce protection (length and frequency of RIPC) have been examined in those studies although, as with direct ischemic PC, caution may be needed in translating that data to human (see below). In addition, there have not been studies looking at the effects of gender and co-morbidities in RIPC (at least with respect to cerebral ischemia).

Another form of PC stimulus is that induced by the volatile anesthetics, isoflurane, sevoflurane, xenon and halothane (Clarkson 2007; Wang, Traystman et al. 2008; Dirnagl, Becker et al. 2009; Gidday 2010). The PC effects of volatile anesthetics has been shown by multiple groups against global cerebral ischemia (Blanck, Haile et al. 2000; Payne, Akca et al. 2005; Zhang, Yuan et al. 2010) as well as transient (Kitano, Young et al. 2007; Codaccioni, Velly et al. 2009; Li and Zuo 2009) and permanent (Kapinya, Lowl et al. 2002; Zheng and Zuo 2004; Li, Peng et al. 2008). Histological and behavioral endpoints have been used (e.g. (Limatola, Ward et al. 2010; Yu, Chu et al. 2011)) and several species have been studied (Keep, Wang et al. 2010), including the gyrencephalic dog (Blanck, Haile et al. 2000). The effects of isoflurane-induced PC may be less in female rats (Kitano, Young et al. 2007) although the effects of xenon-induced PC were reported to be gender independent (Limatola, Ward et al. 2010). This requires further investigation, as do the effects of stroke co-morbidities on efficacy. A major advantage of using volatile anesthetics for PC is that anesthesia can be used as a biomarker to indicate that appropriate drug levels have been reached in the brain.

Pre-clinical Data for Preconditioning: Special Requirements?

From the above description, it is evident that there is considerable pre-clinical evidence on PC with respect to the STAIR criteria. However, although the current STAIR (Fisher, Feuerstein et al. 2009) and RIGOR criteria broadly apply to PC studies, there are issues that require different emphasis (compared to other neuroprotectants), as discussed below.

-

Dosing/Safety. The STAIR criteria for neuroprotectants notes that preclinical studies should determine a minimum effective and a maximum tolerated dose (Fisher, Feuerstein et al. 2009) and that such studies should allow determination of a target concentration and whether such a concentration (at the target tissue) may be reached during clinical administration. This raises several issues with respect to PC. First, the range between minimum effective and maximum tolerated dose may be very narrow. PC stimuli mostly act by inducing cellular stress, raising the question of whether they may be causing some effect on cellular function, even if they do not cause permanent damage. Thus, for example, while a short duration of focal ischemia used to induce PC in the rat did not cause an infarct it did cause behavioral deficits (Hua, Wu et al. 2005). Second, some PC stimuli are not pharmacological raising the question of how to titrate the stimuli ‘dose’ between species? For ischemic PC, should the duration of transient vascular occlusion to induce PC be the same across species as it may well vary with collateral flow for both the duration required to induce PC and the duration that will cause injury?

Third, matters are even more complicated with RIPC where the safety issue is thought to mostly reside in the limb being made transiently ischemic but the efficacy is at a remote site, the brain. A maximum tolerated exposure to RIPC can be determined (number of ischemic events and duration of those events) by examining tissue parameters and, in humans, by direct patient communication (Koch, Katsnelson et al. 2011; Bilgin-Freiert, Dusick et al. 2012). However, determining whether a particular form of RIPC will be sufficient to cause protection is more problematic without actually performing efficacy trials. It is tempting to translate data (number and duration of ischemic events) from animal studies to human. However, it should be noted that apart from other potential dissimilarities, the ratio of limb size to body weight can vary greatly between species. More data is needed on RIPC requirements across species. In addition, one method of potentially addressing this issue would be the development of biomarkers, e.g. are there factors in blood that can monitor the relative impact of RIPC regimens across species and in humans?

Translation of data between different forms of PC. While studies demonstrating that multiple types of PC stimuli can protect the brain from injury serve to underline the therapeutic potential of PC, they do raise important questions. How do PC stimuli compare in terms of efficacy, ease of application and safety? In general, there is a lack of direct data on this issue. Pera et al. (Pera, Zawadzka et al. 2004) found that ischemic PC caused a greater reduction in infarct volume after transient focal cerebral ischemia than PC with 3-nitroproprionic acid, but Puisieux et al. (Puisieux, Deplanque et al. 2000) found a similar degree of protection with ischemic- and lipopolysaccharide-induced PC. Comparisons of the effects of remote and direct ischemic PC would be very useful preclinical data for justifying RIPC use in clinical trials. The relative safety and ease of application are major factors driving the use of RIPC. Given the diversity of PC modalities and wide range of merits and potential safety concerns, studies that directly compare different PC treatments in the same injury model would be highly informative.

Therapeutic time window. One consideration in the STAIR criteria is the therapeutic time window, i.e. for how long after a stroke can treatment be given and still be protective, and for how long should a drug be administered (Fisher, Feuerstein et al. 2009). For PC there are different ‘time’ considerations that should be examined for a potential stimulus. First, does the PC stimulus cause early and/or delayed PC? Clinically, the former would be easier to implement (e.g. administration just prior to surgery rather than requiring patient access a day earlier), although that might be offset if delayed PC provides greater efficacy. The second is how long do the effects of PC last? One potential use of PC is as a prophylactic in patients who are risk of a stroke (such as patients with a recent stroke; (Keep, Wang et al. 2010)). The utility of such an approach depends on the duration of protection and, depending on the length of protection required, whether a PC stimulus can be re-administered and still be effective. Due to the considerable influence of timing on the efficacy of PC in animal models, it is essential that more sophisticated studies of onset and offset of PC treatments are performed; the breadth of these timing studies will very likely go beyond what is conventionally expected in the STAIR recommendations.

-

Comorbidities. One of the major recommendations of the STAIR criteria is the testing of potential therapeutics in models expressing relevant comorbidities. For example, for ischemic stroke, these include using aged, hypertensive and diabetic animals. There are concerns co-morbidities may reduce therapeutic effectiveness, concerns that also apply to PC. Thus, there is evidence that aging and hypertension blunt the protective effects of ischemic PC in brain (Purcell, Lenhard et al. 2003; He, Crook et al. 2005; Schaller 2007) and, in heart, there is evidence that hypercholesterolemia, obesity and diabetes reduce the effectiveness of PC (Przyklenk 2011; Sack and Murphy 2011).

There is also a concern that a comorbid condition may of itself cause an upregulation of endogenous defense mechanisms so that a further PC stimulus is unable to cause further protection. While this has not been directly examined in brain, there is evidence that some pathophysiological changes may induce PC. Thus, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion can act as a PC stimulus protecting against a later stroke (Kim, Kim et al. 2008) and there is also some evidence that transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) may have the same effect (Wegener, Gottschalk et al. 2004). Similarly, in a rat periodontitis model, the mild systemic inflammation protects against a later transient focal cerebral ischemia (Petcu, Kocher et al. 2008).

Surgical interventions. The potential use of PC in relation to surgical interventions raises another issue that should be examined in pre-clinical studies, that is whether the current surgical practice may contain elements that may already act as a PC stimulus, thus negating the need (or effect) of another PC stimulus. For example, there is considerable evidence that volatile anesthetics (e.g. isoflurane) can induce PC (Kapinya, Lowl et al. 2002). It is also possible that transient applied vascular occlusions during surgery may also cause PC. It is, therefore, important to examine the effects of a PC stimulus in preclinical models that mimic as closely as possible any surgical intervention.

-

Translation between different ‘ischemia models’. The effects of different PC stimuli have been examined in multiple pre-clinical models of cerebral ischemia. Thus, for example, ischemic PC has shown protection in global, transient focal and permanent focal cerebral ischemia (Gidday 2006; Obrenovitch 2008; Gidday 2010; Keep, Wang et al. 2010). However, a question arises over whether those results can be translated to other conditions where there is an ischemic component to brain damage? For example, in traumatic brain injury, ischemia is thought to play a role in tissue damage but the injury mechanisms are multifactorial (e.g. involving direct physical damage and hemorrhage; (Maas, Stocchetti et al. 2008)). Thus it is important to examine the effects of PC directly in preclinical traumatic brain injury models and there have been limited studies along those lines (Perez-Pinzon, Alonso et al. 1999; Longhi, Gesuete et al. 2011).

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is another condition with an ischemic component. There is an initial ischemic event at the time of hemorrhage and a delayed cerebral ischemia that develops days later in many patients. The use of PC to ameliorate this delayed ischemic injury has been the subject of two pilot clinical trials using RIPC (NCT01158508; NCT01110239; (Koch, Katsnelson et al. 2011; Bilgin-Freiert, Dusick et al. 2012)). It should be noted that we are using the term PC because the stimuli is being given before the delayed ischemic event although it is being given after the initial SAH. Using RIPC in SAH addresses two of the major concerns about PC, safety and how to know when an ischemic event will occur. RIPC is thought to be generally safe and the effects on the ischemic limb can be monitored (Gonzalez and Liebeskind 2011; Koch, Katsnelson et al. 2011; Bilgin-Freiert, Dusick et al. 2012) and delayed cerebral ischemia is known to occur in a subset of SAH patients (~30%) during the first two weeks (Vergouwen and Participants in the International Multi-Disciplinary Consensus Conference on the Critical Care Management of Subarachnoid 2011). However, there is very limited preclinical data on the effects of PC on SAH (Ostrowski, Colohan et al. 2005; Ostrowski, Tang et al. 2006; Chang, Wu et al. 2010; Vellimana, Milner et al. 2011) and the use of PC in this condition raises some specific issues. When the PC stimulus is given after the ictus, there is the possibility of the stimulus, usually a stressor, impacting and potentially worsening the initial injury. This requires further investigation. There is also some evidence that PC impacts the coagulation cascade with increased bleeding times (Stenzel-Poore, Stevens et al. 2003; He, Karabiyikoglu et al. 2012). Although the effects are fairly small, the impact of PC on the chances of potential re-hemorrhaging requires further investigation. As noted above, the SAH often causes an initial ischemia which is then followed by a delayed ischemic event. It is possible that the initial ischemic event may induce protective mechanisms which serve to ameliorate the later ischemia, i.e. it may act as a PC stimulus. This may limit the ability of a further exogenous PC stimulus to induce protection.

Ischemia and intracerebral hemorrhage. As well as the plethora of preclinical data on the effects of PC on ischemic brain injury, there is also evidence that some PC stimuli may also protect against intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain damage (Xi, Hua et al. 2000; Qin, Song et al. 2007; Gigante, Appelboom et al. 2011). However, interestingly, a recent study of remote ischemic post-conditioning found no protective effect against intracerebral hemorrhage (Geng, Ren et al. 2012) although that paradigm protects against ischemic brain damage. While it may not be essential to have preclinical data on whether a particular PC stimulus protects against both ischemia- and hemorrhage-induced brain injury, such data may extend the usefulness of that PC stimulus. For example, PC might be considered before a neurosurgical intervention that carries a risk of hemorrhage and ischemia or in patients with ‘mixed cerebrovascular disease’ where both ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebrovascular disease co-exist (Fisher, Vasilevko et al. 2012).

Overall, PC studies are distinguished from ischemic stroke neuroprotection research in a number of respects which necessitate added rigor in PC investigations. Foremost, in any clinical trial of neurological disease, safety is of utmost concern. Since PC generally induces cell stress responses that could damage a vulnerable brain, the therapeutic dosing window may be small and differ markedly across species.

Unlike neuroprotection studies for ischemic stroke, the menu of possible PC disease state targets is wide-ranging; this is evident from the enormous range of target under preliminary investigation (see below). Variant experimental models of each of these disease states have been described, presenting an enormous challenge to interpretation of pre-clinical experiments. It is tempting to speculate that disease states with an ischemic pathophysiology are similar, but PC effects will likely differ in unexpected ways, and thus minor variations between a disease model and the human condition could jeopardize the value of clinical outcomes studies.

Finally, the bimodal temporal dependency of PC that is broadly seen in neurological and non-neurological injury, makes the therapeutic menu complex. When does one start and stop PC to derive maximal effects? Do different doses of PC have different time windows of efficacy? All of these questions bring up issues that go beyond the STAIR recommendations for ischemic stroke.

Where are we with clinical testing?

A small number of human PC studies have now been reported for neurological conditions. Faries et al. has reported that a small number of patients undergoing carotid stenting who had ischemic symptoms after balloon occlusion of the carotid artery were able to tolerate subsequent occlusion just before stenting (Faries, DeRubertis et al. 2008). While observations like this are intriguing, data from randomized trials directly testing the effects of PC are few. A small number of preliminary trial results have been reported. Chan et al. (Chan, Boet et al. 2005) tested the effects of a brief two minute artery occlusion prior to cerebral aneurysm clipping on brain tissue pO2 and pH; ischemic PC was found to benefit physiological parameters, suggesting a potential benefit. Alex et al. (Alex, Laden et al. 2005) tested whether hyperbaric oxygen before CABG could prevent cognitive deficits after cardiac bypass and reported beneficial effects. A biomarker study by Li et al. has examined release of serum indicators of cardiac and neuronal injury after HBO preconditioning for CABG (Li, Dong et al. 2011).

Recently, a number of clinical studies of RIPC have been reported. Walsh et al. (Walsh, Nouraei et al. 2010) have performed a safety-phase trial of RIPC using lower limb ischemia before carotid endarterectomy; no statistically significant differences were seen in a surrogate neurological outcome (delayed saccades), but the procedure appeared safe and viable for further testing. Hoole and colleagues found that RIPC prior to coronary artery stenting significantly decreased a combined cardiac and cerebral adverse effect endpoint (Hoole, Heck et al. 2009). Hu performed a study of RIPC (arm cuff) to prevent perioperative injury in cervical cord decompression. This study demonstrated decreased serum markers of neuronal injury and increase rate of recovery but did not show differences in electrophysiological transmission through the cord (Hu, Dong et al. 2010). Recently, Koch and colleagues performed a phase Ib trial of RIPC after SAH and found that critically ill patients could tolerate lower limb ischemic procedures (Koch, Katsnelson et al. 2011); this study may lead into larger, definitive trials.

According to ClinicalTrials.org, 23 clinical trials are currently being conducted for PC against neurological outcomes (Table 2). There is international interest in application of this concept, as multiple trials are listed in North America, Europe, and Asia. A vast majority (17 of 23) of the clinical trials are using RIPC, perhaps driven by theoretical safety of this treatment compared to unknown risks of pharmacologic agents which may stress the brain directly. Hyperbaric oxygen and sevoflurane are being used in two pairs of trials, and another involves acupuncture. The diseases/conditions studied are heterogeneous, and include cardiac bypass surgery (the most common target; 11 of 23 trials), carotid surgery, coronary artery stenting, SAH, aneurysm treatment, cervical decompression surgery, and abdominal surgery. Many of the trials for cardiac surgery will measure both cardiac and neurological outcome (as either a primary, combined, or secondary outcome).

Table 2.

Ongoing and unpublished trials of preconditioning with neurological outcome measures

| Intervention | Condition | Neurological outcomes* |

NCT number | Contact | Trial name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | Neurological events and vasospasm (1) | NCT01158508 | NR Gonzalez | Remote Ischemic Preconditioning in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (RIPC-SAH) |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | Tolerability and safety (1) | NCT01110239 | S Koch | Preconditioning for Aneurismal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Secondary stroke prevention | MRI lesions (1) | NCT01321749 | X Ji | The Neuroprotective Effect of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning on Ischemic Cerebral Vascular Disease |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Symptomatic cerebral artery disease | Safety and feasibility and serum markers (1) | NCT01570231 | X Ji | Feasibility, Safety and Efficacy of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning for Symptomatic Intracranial Arterial Stenosis in Octogenarians |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Ischemic stroke after tPA | Infarct growth on MRI (1) | NCT00975962 | G Andersen | New Acute Treatment for Stroke - The Effect of Remote PERconditioning |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Carotid stenting | Cognition, serum markers, MRI lesions (1) | NCT01175876 | X Ji | The Effect Of Remote Limb Ischemic Preconditioning For Carotid Artery Stenting |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Coronary artery bypass grafting | Stroke (1) | NCT01247545 | DJ Hausenloy | Effect of Remote Ischaemic Preconditioning on Clinical Outcomes in CABG Surgery (ERICCA) |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Coronary artery bypass grafting or valve surgery | Serum markers (1) | NCT01231789 | H Dong | The Neuroprotection of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning (RIPC) on Cardiac Surgery in Multicenter |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Cardiac or vascular surgery | Multiple Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) (1) | NCT01328912 | DM Payne | Remote Ischemic Preconditioning in High Risk Cardiovascular Surgery Patients |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Cardiac surgery | Stroke and others (1) | NCT00997217 | YS Jeon | The Effect of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning in the Cardiac Surgery (RIPC) |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Cardiac surgery with bypass | Multiple Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) (1) | NCT01067703 | P Meybohm | Remote Ischaemic Preconditioning for Heart Surgery (RIPHeart-Study) |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Cardiac surgery | Stroke (2) | NCT01071265 | M Walsh | Remote Ischemic Preconditioning in Cardiac Surgery Trial (Remote IMPACT) |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Coronary artery bypass grafting | Stroke (2) | NCT01500369 | A Lotfi | Effect of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning on Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Coronary stenting | Multiple Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) (1) | NCT01078272 | E Haag | The Saint Francis Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Trial (SaFR) |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Percutaneous coronary intervention | Multiple Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) (2) | NCT00435266 | TT Nielsem | Remote Ischemic Preconditioning in Primary PCI |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Cervical decompression surgery | Serum markers (1) | NCT00778323 | L Xiong | Clinical Trial of Remote Preconditioning in Patients Undergoing Cervical Decompression Surgery |

| Remote ischemic preconditioning | Abdominal surgery | Multiple Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) (1) | NCT01340742 | R Lavi | Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Before Abdominal Surgery |

| Hyperbaric oxygen | Coronary artery bypass grafting | Cognition (1) | NCT00817791 | L Xiong | Preconditioning With Hyperbaric Oxygen in Cardiovascular Surgery |

| Hyperbaric oxygen | Coronary artery bypass grafting | Cerebrovascular complications (2) | NCT00623142 | JZ Yogaratnam | The Protective Effects Of Treatment With Hyperbaric Oxygen Prior To Bypass Heart Surgery |

| Sevoflurane | Coronary artery bypass grafting or valve surgery | Stroke (2) | NCT01477151 | PM Jones | Randomized Isoflurane and Sevoflurane Comparison in Cardiac Surgery (RISCCS) |

| Sevoflurane | Aneurysm surgery | Serum markers (1) | NCT01204268 | H Dong | The Neuroprotection of Sevoflurane Preconditioning on Perioperative Ischemia-reperfusion Injury During Intracranial Aneurysm Surgery |

| Erthyromycin | Coronary artery bypass grafting | Serum markers and brain oxygen (1) | NCT01274754 | G Vretzakis | Neuroprotection With Erythromycin in Cardiac Surgery |

| Electroaccupuncture | Aortic or mitral valve surgery | Cerebrovascular events (1) | NCT01020266 | A Weng | Neuroprotective Study of Electroacupuncture Pretreatment in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery |

Search terms: “Preconditioning AND brain,” “Preconditioning AND CNS,” “Preconditioning AND stroke,” “Preconditioning AND Hemorrhage,” “Remote conditioning AND brain,” “Remote conditioning AND stroke” were used on Clinicaltrials.org on 7/29/12. Ongoing and completed studies with neurological outcomes whose results have not been reported are listed.

We only list neurological outcomes of each trial. We denote primary outcomes with (1); if there are no neurological primary outcomes, we list the neurological secondary outcomes denoted with (2).

Clinical targets that have not yet entered clinical trials but have previously been considered as potential targets (Keep, Wang et al. 2010) include: conditions in which traumatic brain injury is likely (combat, sports), general neurosurgical procedures of the brain, seizure-induced injury, inflammatory conditions (meningitis and multiple sclerosis).

Relative strengths and limitations exist for all possible PC targets. In SAH, for example, neurological deficits and mortality is high, possibly reducing the number of subjects needed to test in clinical trials. On the other hand, PC stimuli must be applied to patients who have already experienced brain injury and, thus, some conditioning stimuli could actually be detrimental.

Cardiac surgery and carotid artery interventions, which impose a risk of cognitive impairment and stroke, are common procedures performed in a large number of centers, which potentially allows for large multicenter clinical trials that could accelerate study enrollment. Moreover, since surgery is planned in advance, careful pre-assessment of function using detailed cognitive profiles and advanced image could permit detection followed by post-procedure reassessment may enable sensitive detection of incremental changes after surgery. But a potential limitation of cardiac and carotid surgery as PC targets is that the procedures have matured to the point where the complication rates are now low (Ferguson, Hammill et al. 2002; Silver, Mackey et al. 2011). This limits the power of a study and may necessitate a larger number of enrolled subjects.

Several trials are currently enrolling patients undergoing aneurysm repair. In one study, experimental PC with a mechanism based peptide inhibitor of NMDA-induced neuronal injury is being tested for efficacy in prevention of radiological and functional damage after preplanned aneurysm treatment (Tymianski 2010). Investigators are measuring both clinical outcome measures and MRI lesions that may not be apparent using clinical examination. As a preplanned procedure, a within-subject comparison of cognitive function and MRI is possible. Such studies could potentially be limited by the modest frequency of clinically apparent adverse consequences (5%) but are balanced by the relatively high reported frequency of MRI lesions seen in this clinical context. The availability of even more sensitive biomarkers, made possible by advances in brain imaging, could improve the power of this and other PC studies.

Conclusion

In summary, preclinical studies have reproducibly revealed the potential of PC to prevent neuronal injury induced by multiple disease models. Application of this knowledge to clinical scenarios will be challenging, given the difficulties encountered in translational neuroprotection research. This past history of negative clinical studies, in combination with special requirements for fully characterizing PC treatments, has made it difficult for many to accept that PC is ready for large clinical trials.

A vote of attendants at the 2011 Translational Preconditioning Meeting at the University of Miami revealed a divergence of opinions about whether PC was ready to be tested in clinical trials. Some wondered, might equivocal or failed clinical studies based on incomplete preclinical data taint the water and reduce enthusiasm and funding for an otherwise promising field? Notwithstanding, a real world assessment of ongoing trials indicates that human trials are well-underway. As the research community analyzes the results of these ongoing investigations, regardless of outcome, future studies will need to be conducted. A critical assessment of current preclinical data followed by design of new experiments that bring rigor and improved clinical relevance, which are now, more than ever, being stressed by the scientific community, will likely play a major role in the design of larger, pivotal studies.

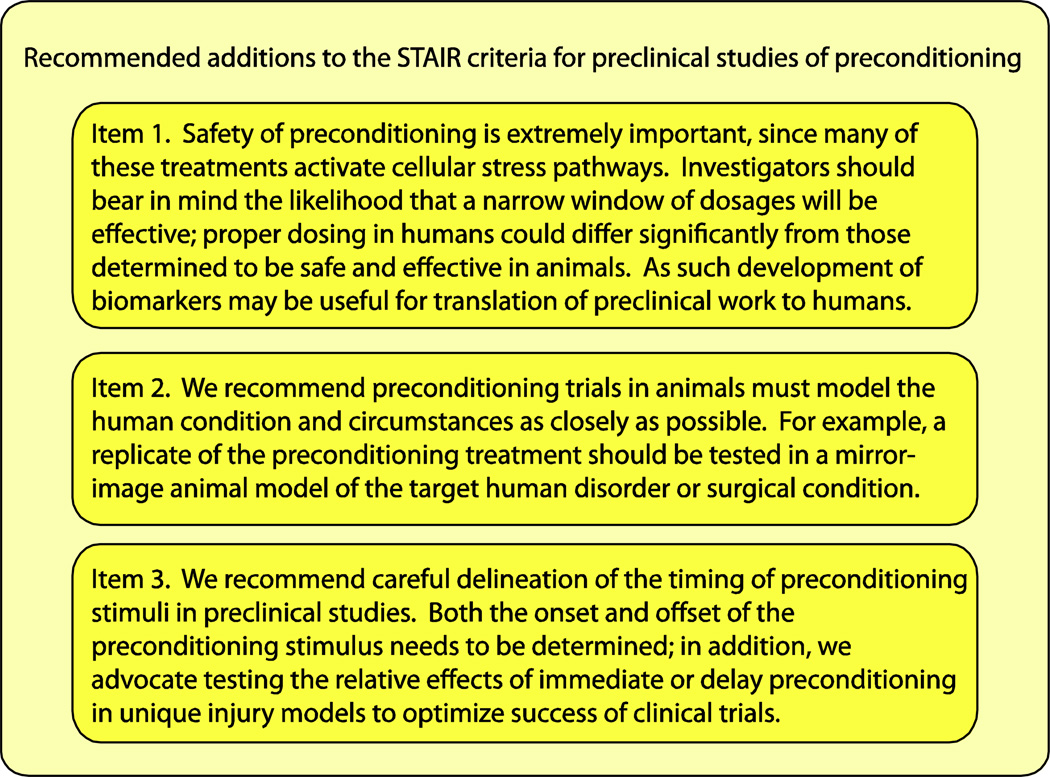

The STAIR and NINDS RIGOR criteria present rational guides for translation of PC to the clinical arena, but we suggest that PC requires a number of additional considerations. In view of the importance of key differences between stroke neuroprotection and PC, we summarize our core recommendations in Figure 2. Among these, the three priority areas for special attention in pre-clinical PC experimentation include: 1) safety and dosage concerns; 2) choice of model to be tested and matching these models to a narrow clinical target; and 3) establishing critical time point information for maximal PC efficacy. We hope that attention to these factors will increase the probability that PC treatments will ultimately succeed at the bedside.

Figure 2.

In addition to the STAIR criteria, three additional emphases of preclinical studies of preconditioning are discussed here. These directions of study are required because of differences between neuroprotection and preconditioning. The latter induces stress pathways and exhibits a biphasic temporal window of efficacy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants NS054724 (MMW), NS039866 (GX), NS34709 (RFK). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

- Abe H, Nowak TS., Jr Induced hippocampal neuron protection in an optimized gerbil ischemia model: insult thresholds for tolerance induction and altered gene expression defined by ischemic depolarization. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24(1):84–97. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000098607.42140.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alex J, Laden G, et al. Pretreatment with hyperbaric oxygen and its effect on neuropsychometric dysfunction and systemic inflammatory response after cardiopulmonary bypass: a prospective randomized double-blind trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(6):1623–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ara J, Fekete S, et al. Hypoxic-preconditioning induces neuroprotection against hypoxia-ischemia in newborn piglet brain. Neurobiology of Disease. 2011;43(2):473–485. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin-Freiert A, Dusick JR, et al. Muscle micodialysis to confirm sublethal ischemia in the induction of remote ischemic preconditioning. Trans. Stroke Res. 2012;3:266–272. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanck TJ, Haile M, et al. Isoflurane pretreatment ameliorates postischemic neurologic dysfunction and preserves hippocampal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in a canine cardiac arrest model. Anesthesiology. 2000;93(5):1285–1293. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200011000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambrink AM, Koerner IP, et al. The antibiotic erythromycin induces tolerance against transient global cerebral ischemia in rats (pharmacologic preconditioning) Anesthesiology. 2006;104(6):1208–1215. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MTV, Boet R, et al. Effect of ischemic preconditioning on brain tissue gases and pH during temporary cerebral artery occlusion. Acta Neurochirurgica - Supplement. 2005;95:93–96. doi: 10.1007/3-211-32318-x_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-Z, Wu S-C, et al. Atorvastatin preconditioning attenuates the production of endothelin-1 and prevents experimental vasospasm in rats. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2010;152(8):1399–1406. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0652-3. discussion 1405-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Graham SH, et al. Stress proteins and tolerance to focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16(4):566–577. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng O, Ostrowski RP, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 mediates hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning in the rat model of transient global cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2011;42(2):484–490. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson AN. Anesthetic-mediated protection/preconditioning during cerebral ischemia. Life Sciences. 2007;80(13):1157–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codaccioni J-L, Velly LJ, et al. Sevoflurane preconditioning against focal cerebral ischemia: inhibition of apoptosis in the face of transient improvement of neurological outcome. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(6):1271–1278. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a1fe68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley NA, Sena E, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in the design of experimental stroke studies: a metaepidemiologic approach. Stroke. 2008;39(3):929–934. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.498725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave KR, Saul I, et al. Remote organ ischemic preconditioning protect brain from ischemic damage following asphyxial cardiac arrest. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;404(1–2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, Becker K, et al. Preconditioning and tolerance against cerebral ischaemia: from experimental strategies to clinical use. Lancet Neurology. 2009;8(4):398–412. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowden J, Corbett D. Ischemic preconditioning in 18- to 20-month-old gerbils: long-term survival with functional outcome measures. Stroke. 1999;30(6):1240–1246. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.6.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks SL, Brambrink AM. Preconditioning and postconditioning for neuroprotection: the most recent evidence. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Anaesthesiology. 2010;24(4):521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faries PL, DeRubertis B, et al. Ischemic preconditioning during the use of the PercuSurge occlusion balloon for carotid angioplasty and stenting. Vascular. 2008;16(1):1–9. doi: 10.2310/6670.2008.00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TB, Jr, Hammill BG, et al. A decade of change--risk profiles and outcomes for isolated coronary artery bypass grafting procedures, 1990–1999: a report from the STS National Database Committee and the Duke Clinical Research Institute. Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(2):480–489. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03339-2. discussion 489–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein GZ, Zaleska MM, et al. Missing steps in the STAIR case: a Translational Medicine perspective on the development of NXY-059 for treatment of acute ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(1):217–219. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, et al. Recommendations for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development. Stroke. 1999;30(12):2752–2758. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Feuerstein G, et al. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2244–2250. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Vasilevko V, et al. Mixed Cerebrovascular Disease and the Future of Stroke Prevention. Transl Stroke Res. 2012;3(Suppl 1):39–51. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0185-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng X, Ren C, et al. Effect of remote ischemic postconditioning on an intracerebral hemorrhage stroke model in rats. Neurological Research. 2012;34(2):143–148. doi: 10.1179/1743132811Y.0000000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidday JM. Cerebral preconditioning and ischaemic tolerance. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(6):437–448. doi: 10.1038/nrn1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidday JM. Cerebral preconditioning and ischaemic tolerance. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7(6):437–448. doi: 10.1038/nrn1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidday JM. Pharmacologic Preconditioning: Translating the Promise. Transl Stroke Res. 2010;1(1):19–30. doi: 10.1007/s12975-010-0011-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigante PR, Appelboom G, et al. Isoflurane preconditioning affords functional neuroprotection in a murine model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochirurgica - Supplement. 2011;111:141–144. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg MD. Neuroprotection for ischemic stroke: past, present and future. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55(3):363–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez NR, Liebeskind DS. Letter by Gonzalez and Liebeskind regarding article, "remote ischemic limb preconditioning after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a phase Ib study of safety and feasibility". Stroke. 2011;42(9):e553. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.622464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AR. Pharmacological approaches to acute ischaemic stroke: reperfusion certainly, neuroprotection possibly. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S325–S338. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn CD, Manlhiot C, et al. Remote ischemic per-conditioning: a novel therapy for acute stroke? Stroke. 2011;42(10):2960–2962. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.622340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Remote ischaemic preconditioning: underlying mechanisms and clinical application. Cardiovascular Research. 2008;79(3):377–386. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YD, Karabiyikoglu M, et al. Ischemic Preconditioning Attenuates Brain Edema After Experimental Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Translational Stroke Research. 2012;3:S180–S187. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0171-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Crook JE, et al. Aging blunts ischemic-preconditioning-induced neuroprotection following transient global ischemia in rats. Current Neurovascular Research. 2005;2(5):365–374. doi: 10.2174/156720205774962674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoole SP, Heck PM, et al. Cardiac Remote Ischemic Preconditioning in Coronary Stenting (CRISP Stent) Study: a prospective, randomized control trial. Circulation. 2009;119(6):820–827. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.809723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Dong HL, et al. Effects of remote ischemic preconditioning on biochemical markers and neurologic outcomes in patients undergoing elective cervical decompression surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2010;22(1):46–52. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181c572bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Y, Wu J, et al. Ischemic preconditioning procedure induces behavioral deficits in the absence of brain injury? Neurol Res. 2005;27(3):261–267. doi: 10.1179/016164105X25270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen HA, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Remote ischemic preconditioning protects the brain against injury after hypothermic circulatory arrest. Circulation. 2011;123(7):714–721. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen HA, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Protects the Brain Against Injury After Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest. Circulation. 2011;123(7):714–721. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapinya KJ, Lowl D, et al. Tolerance against ischemic neuronal injury can be induced by volatile anesthetics and is inducible NO synthase dependent. Stroke. 2002;33(7):1889–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020092.41820.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keep RF, Wang MM, et al. Is There A Place For Cerebral Preconditioning In The Clinic? Transl Stroke Res. 2010;1(1):4–18. doi: 10.1007/s12975-009-0007-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keep RF, Wang MM, et al. Is there a place for preconditioning in the clinic? Trans. Stroke Res. 2010;1:4–18. doi: 10.1007/s12975-009-0007-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharbanda RK, Nielsen TT, et al. Translation of remote ischaemic preconditioning into clinical practice. Lancet. 2009;374(9700):1557–1565. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Kim EH, et al. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion protects against acute focal ischemia, improves motor function, and results in vascular remodeling. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2008;5(1):28–36. doi: 10.2174/156720208783565627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino T, Nakagomi T, et al. Ischemic tolerance. Advances in Neurology. 1996;71:505–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H, Young JM, et al. Gender-specific response to isoflurane preconditioning in focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(7):1377–1386. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch S, Katsnelson M, et al. Remote ischemic limb preconditioning after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a phase Ib study of safety and feasibility. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1387–1391. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner IP, Gatting M, et al. Induction of cerebral ischemic tolerance by erythromycin preconditioning reprograms the transcriptional response to ischemia and suppresses inflammation. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(3):538–547. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200703000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Peng L, et al. Isoflurane preconditioning increases B-cell lymphoma-2 expression and reduces cytochrome c release from the mitochondria in the ischemic penumbra of rat brain. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;586(1–3):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning improves short-term and long-term neurological outcome after focal brain ischemia in adult rats. Neuroscience. 2009;164(2):497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Dong H, et al. Preconditioning with repeated hyperbaric oxygen induces myocardial and cerebral protection in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011;25(6):908–916. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limatola V, Ward P, et al. Xenon preconditioning confers neuroprotection regardless of gender in a mouse model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neuroscience. 2010;165(3):874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhi L, Gesuete R, et al. Long-lasting protection in brain trauma by endotoxin preconditioning. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2011;31(9):1919–1929. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludman AJ, Yellon DM, et al. Cardiac preconditioning for ischaemia: lost in translation. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2010;3(1–2):35–38. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas AI, Stocchetti N, et al. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(8):728–741. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod MR, O'Collins T, et al. Systematic review and metaanalysis of the efficacy of FK506 in experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25(6):713–721. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod MR, van der Worp HB, et al. Evidence for the efficacy of NXY-059 in experimental focal cerebral ischaemia is confounded by study quality. Stroke. 2008;39(10):2824–2829. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.515957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra S, Naggar I, et al. Neurogenic pathway mediated remote preconditioning protects the brain from transient focal ischemic injury. Brain Research. 2011;1386:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchett GA, Martin RD, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy and cerebral ischemia: neuroprotective mechanisms. Neurological Research. 2009;31(2):114–121. doi: 10.1179/174313209X389857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miljkovic-Lolic M, Silbergleit R, et al. Neuroprotective effects of hyperbaric oxygen treatment in experimental focal cerebral ischemia are associated with reduced brain leukocyte myeloperoxidase activity. Brain Research. 2003;971(1):90–94. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry CE, Jennings RB, et al. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74(5):1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasu I, Yokoo N, et al. The dose-dependent effects of isoflurane on outcome from severe forebrain ischemia in the rat. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2006;103(2):413–418. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000223686.50202.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Collins VE, Macleod MR, et al. 1,026 experimental treatments in acute stroke. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):467–477. doi: 10.1002/ana.20741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrenovitch TP. Molecular physiology of preconditioning-induced brain tolerance to ischemia. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(1):211–247. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrenovitch TP. Molecular physiology of preconditioning-induced brain tolerance to ischemia. Physiological Reviews. 2008;88(1):211–247. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski RP, Colohan ART, et al. Mechanisms of hyperbaric oxygen-induced neuroprotection in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2005;25(5):554–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski RP, Tang J, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen suppresses NADPH oxidase in a rat subarachnoid hemorrhage model. Stroke. 2006;37(5):1314–1318. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217310.88450.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne RS, Akca O, et al. Sevoflurane-induced preconditioning protects against cerebral ischemic neuronal damage in rats. Brain Research. 2005;1034(1–2):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pera J, Zawadzka M, et al. Influence of chemical and ischemic preconditioning on cytokine expression after focal brain ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78(1):132–140. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Alonso O, et al. Induction of tolerance against traumatic brain injury by ischemic preconditioning. Neuroreport. 1999;10(14):2951–2954. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199909290-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petcu EB, Kocher T, et al. Mild systemic inflammation has a neuroprotective effect after stroke in rats. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2008;5(4):214–223. doi: 10.2174/156720208786413424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przyklenk K. Efficacy of cardioprotective 'conditioning' strategies in aging and diabetic cohorts: the co-morbidity conundrum. Drugs & Aging. 2011;28(5):331–343. doi: 10.2165/11587190-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puisieux F, Deplanque D, et al. Differential role of nitric oxide pathway and heat shock protein in preconditioning and lipopolysaccharide-induced brain ischemic tolerance. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;389(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00893-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell JE, Lenhard SC, et al. Strain-dependent response to cerebral ischemic preconditioning: differences between spontaneously hypertensive and stroke prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;339(2):151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01476-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z, Song S, et al. Preconditioning with hyperbaric oxygen attenuates brain edema after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosurgical Focus. 2007;22(5):E13. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.5.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehni AK, Shri R, et al. Remote ischaemic preconditioning and prevention of cerebral injury. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 2007;45(3):247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C, Gao X, et al. Limb remote-preconditioning protects against focal ischemia in rats and contradicts the dogma of therapeutic time windows for preconditioning. Neuroscience. 2008;151(4):1099–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack MN, Murphy E. The role of comorbidities in cardioprotection. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2011;16(3–4):267–272. doi: 10.1177/1074248411408313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz SI. A critical appraisal of the NXY-059 neuroprotection studies for acute stroke: a need for more rigorous testing of neuroprotective agents in animal models of stroke. Exp Neurol. 2007;205(1):20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena P, Bala A, et al. Does remote ischemic preconditioning prevent delayed hippocampal neuronal death following transient global cerebral ischemia in rats? Perfusion. 2009;24(3):207–211. doi: 10.1177/0267659109346902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena P, Bala A, et al. Does remote ischemic preconditioning prevent delayed hippocampal neuronal death following transient global cerebral ischemia in rats? Perfusion-Uk. 2009;24(3):207–211. doi: 10.1177/0267659109346902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller BJ. Influence of age on stroke and preconditioning-induced ischemic tolerance in the brain. Experimental Neurology. 2007;205(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251. e1000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver FL, Mackey A, et al. Safety of stenting and endarterectomy by symptomatic status in the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy Versus Stenting Trial (CREST) Stroke. 2011;42(3):675–680. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.610212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger HJ, Hanggi D. Ischaemic preconditioning of the brain, mechanisms and applications. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2007;149(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00701-006-1057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel-Poore MP, Stevens SL, et al. Effect of ischaemic preconditioning on genomic response to cerebral ischaemia: similarity to neuroprotective strategies in hibernation and hypoxia-tolerant states. Lancet. 2003;362(9389):1028–1037. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland BA, Minnerup J, et al. Neuroprotection for ischaemic stroke: Translation from the bench to the bedside. Int J Stroke. 2012;7(5):407–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymianski M. Can molecular and cellular neuroprotection be translated into therapies for patients?: yes, but not the way we tried it before. Stroke. 2010;41(10 Suppl):S87–S90. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Worp HB, Sena ES, et al. Hypothermia in animal models of acute ischaemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 12):3063–3074. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellimana AK, Milner E, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase mediates endogenous protection against subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced cerebral vasospasm. Stroke. 2011;42(3):776–782. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergouwen MDI H. Participants in the International Multi-Disciplinary Consensus Conference on the Critical Care Management of Subarachnoid. Vasospasm versus delayed cerebral ischemia as an outcome event in clinical trials and observational studies. Neurocritical Care. 2011;15(2):308–311. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9586-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SR, Nouraei SA, et al. Remote Ischemic Preconditioning for Cerebral and Cardiac Protection During Carotid Endarterectomy: Results From a Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2010;44(6):434–439. doi: 10.1177/1538574410369709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Traystman RJ, et al. Inhalational anesthetics as preconditioning agents in ischemic brain. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2008;8(1):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li X, et al. Activation of epsilon protein kinase C-mediated anti-apoptosis is involved in rapid tolerance induced by electroacupuncture pretreatment through cannabinoid receptor type 1. Stroke. 2011;42(2):389–396. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Peng Y, et al. Pretreatment with electroacupuncture induces rapid tolerance to focal cerebral ischemia through regulation of endocannabinoid system. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2157–2164. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Wang F, et al. Electroacupuncture pretreatment attenuates cerebral ischemic injury through alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated inhibition of high-mobility group box 1 release in rats. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Xiong L, et al. Rapid tolerance to focal cerebral ischemia in rats is induced by preconditioning with electroacupuncture: window of protection and the role of adenosine. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;381(1–2):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener S, Gottschalk B, et al. Transient ischemic attacks before ischemic stroke: preconditioning the human brain? A multicenter magnetic resonance imaging study. Stroke. 2004;35(3):616–621. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000115767.17923.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei DT, Ren CC, et al. The Chronic Protective Effects of Limb Remote Preconditioning and the Underlying Mechanisms Involved in Inflammatory Factors in Rat Stroke. Plos One. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi G, Hua Y, et al. Induction of colligin may attenuate brain edema following intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochirurgica - Supplement. 2000;76:501–505. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6346-7_105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Lu Z, et al. Pretreatment with repeated electroacupuncture attenuates transient focal cerebral ischemic injury in rats. Chinese Medical Journal. 2003;116(1):108–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Gong Z, et al. Remote ischemic preconditioning protects neurocognitive function of rats following cerebral hypoperfusion. Medical Science Monitor. 2011;17(11):BR299–BR304. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita S, Hirata T, et al. Repeated preconditioning with hyperbaric oxygen induces neuroprotection against forebrain ischemia via suppression of p38 mitogen activated protein kinase. Brain Research. 2009;1301:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C-H, Wang Y-C, et al. Ischemic preconditioning or heat shock pretreatment ameliorates neuronal apoptosis following hypothermic circulatory arrest. Journal of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgery. 2004;128(2):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Chu M, et al. Sevoflurane preconditioning protects blood-brain-barrier against brain ischemia. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2011;3:978–988. doi: 10.2741/e303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung LM, Wei Y, et al. Sphingosine kinase 2 mediates cerebral preconditioning and protects the mouse brain against ischemic injury. Stroke. 2012;43(1):199–204. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H-P, Yuan L-b, et al. Isoflurane preconditioning induces neuroprotection by attenuating ubiquitin-conjugated protein aggregation in a mouse model of transient global cerebral ischemia. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2010;111(2):506–514. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e45519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning induces neuroprotection against ischemia via activation of P38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;65(5):1172–1180. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]