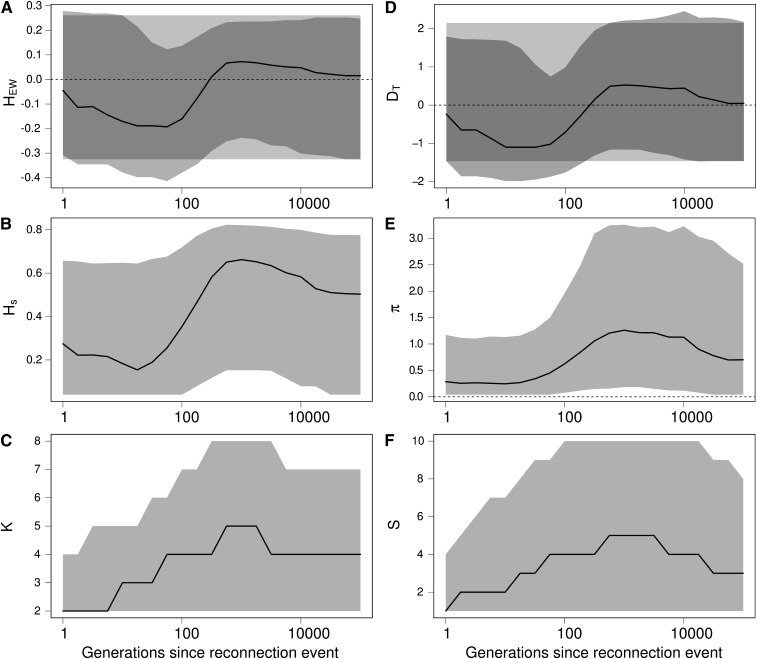

Figure 6.

Effect of a reconnection event on Ewens–Watterson and Tajima’s D neutrality tests and on related summary statistics. (A) Ewens–Watterson statistics (HEW), (B) genetic diversity (Hs), (C) number of alleles (K), (D) Tajima’s D (DT), (E) number of pairwise differences (π), and (F) number of segregating sites (S). For each statistics, the solid line represents the median of the distribution, and the light shading represents the 97.5% and 2.5% quantiles of the distribution, as a function of the number of generations t after the isolation event. Dark shading in A and D represent the expected distribution of the statistics in an isolated equilibrium population. Values of HEW and D after a reconnection event are first skewed toward negative values (signature of a population expansion or balancing selection) and then toward positive values (signature of a bottleneck or directional selection), while there was no change in the size of the population. K and S first increase more quickly than Hs and π because immigrants bring rare alleles, and then Hs and π reach a higher value because immigrant alleles increase in frequency. Finally, alleles are eliminated by genetic drift until the statistics reach their expected equilibrium value when populations are connected. Coalescence simulations of a 1 kb locus with a mutation rate of 2 × 10−8 per bp, where 4 populations of size 2500 isolated during 25,000 generations are reconnected with a migration rate m = 0.002; 5000 replicates.