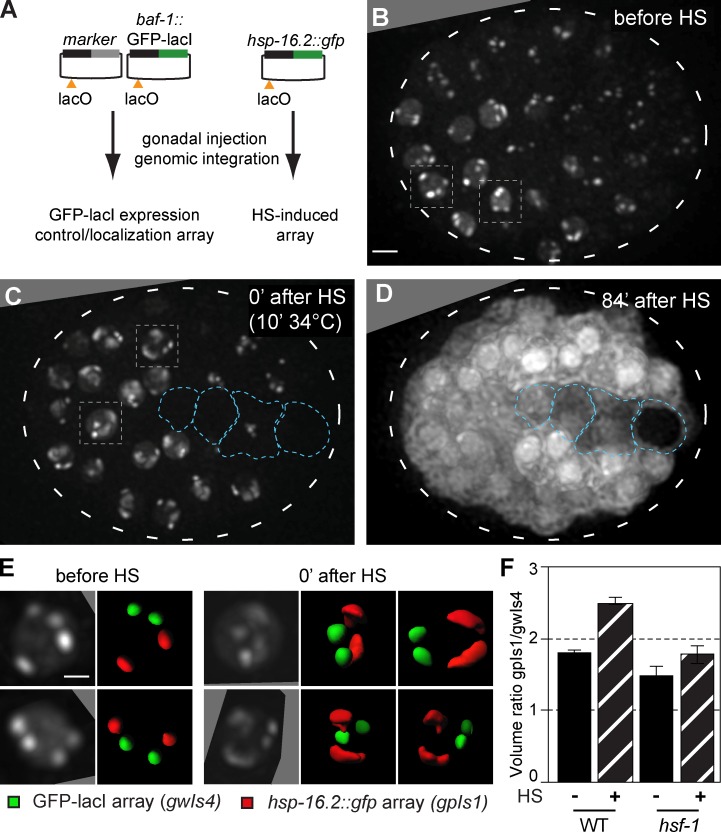

Figure 1.

HS-induced transcription leads to peripheral decondensation of large, HS-inducible arrays. (A) Plasmids used to create large arrays by gonadal injection, bearing either baf-1::GFP-lacI with a muscle-specific marker (gwIs4) or the hsp-16.2 promoter driving GFP (gpIs1), and a single lacO site per plasmid. Arrays contain 250–500 plasmid copies. (B) Fluorescence from an embryo of a strain carrying both gwIs4 and gpIs1 is shown, before HS induction. Four spots reflecting the large integrated gene arrays are located at the nuclear periphery (Meister et al., 2010b; Towbin et al., 2012). Boxed nuclei are enlarged in E. See Fig. S1. Bar, 5 µm. (C) Fluorescence from the same embryo in B after 10 min at 34°C. Boxed nuclei, enlarged in E, show decondensation of two of the arrays. Blue encircled nuclei do not respond to HS. (D) Pervasive cytoplasmic fluorescence from the same embryo in B and C captured 84 min after HS, showing hsp-16.2::gfp induction from the gpIs1 array. Entire embryos are encircled by broken lines. (E) Enlarged nuclei from the embryo in B and C, with two 90° rotations for C. Array volume rendering shows no shift in subnuclear localization of gwIs4 (green) or gpIs1 (red), decondensed at 0 min after HS. Bar, 2 µm. (F) Array volume was quantified using the GFP-lacI signals in WT and hsf-1 mutant worms, presented as the ratio of gwIs4 and HS-activated gpIs1 before and 0 min after HS (WT; n = 100, 11; hsf-1 mutant; n = 3, 6). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.