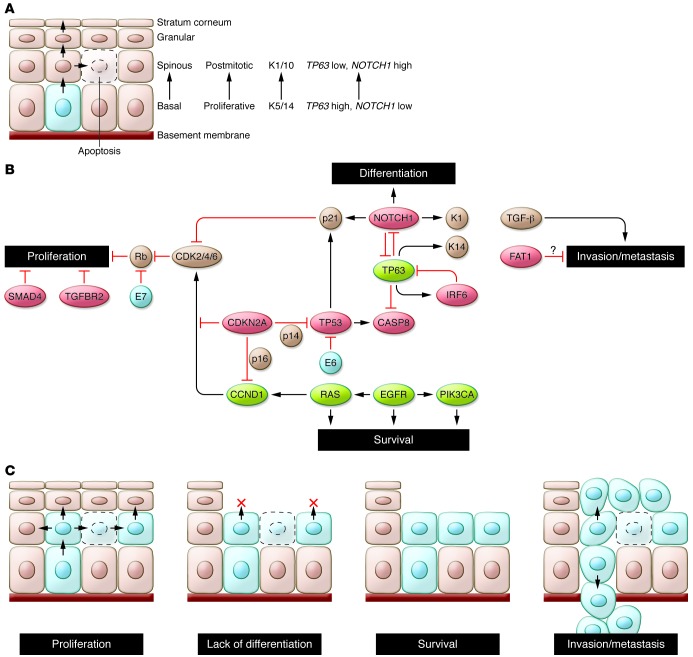

Figure 1. Hallmarks of head and neck squamous tumorigenesis.

(A) The normal process of squamous morphogenesis in the adult mucosa is controlled in part by TP63 and NOTCH1. The former is expressed in keratinocytes of the basal layer, where it maintains their proliferative potential and controls expression of basal markers (e.g., keratins 5/14 [K5/14]); expression of the latter results in terminal differentiation into cells of the spinous (K1/10) and granular layers. Rare stem cells in the basal layer (light blue) undergo terminal differentiation through asymmetric cell division. Abnormal proliferation is prevented primarily by differentiation-associated cell cycle exit and by apoptosis. (B) Pathways altered in HNSCC pathogenesis identified in whole-exome sequencing studies. Red: putative and established tumor suppressors; green: oncogenes; brown: other relevant genes/proteins; blue: viral proteins. Loss of TP53 and CDKN2A, amplification of CCND1, and loss of TGFBR2/SMAD4 permit abnormal proliferation and decrease apoptosis. However, abnormal cell cycling may still be restrained by intact differentiation and apoptotic programs. Loss of NOTCH1 and/or abnormal expression of TP63, together with alterations in “survival” genes (e.g., CASP8, PIK3CA, EGFR), may remove additional barriers to tumor cell proliferation and survival. Loss of cell adhesion genes (e.g., FAT1) could permit release of cells from the mucosal lining, while invasion through the basement membrane is promoted by TGFB1 (and SMAD3). (C) Schematic of HNSCC hallmarks. The precise order of acquisition of distinct alterations is not clear. In addition, several genes (e.g., TP53, TP63, NOTCH1) may contribute to more than one hallmark.