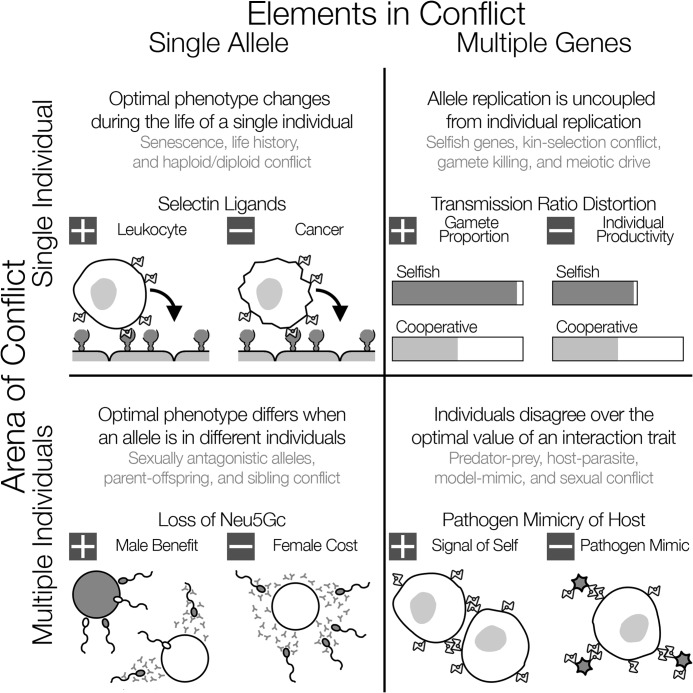

FIGURE 1.

Evolutionary conflicts between alleles and individuals. For single allele-single individual, single alleles conflict with themselves when their positive effects in one context cause negative effects in another. Selectins on epithelial cells bind glycans on leukocytes and guide them to sites of inflammation; this can also be exploited by cancer cells (72). Regulatory or functional changes that separate conflicting tasks are expected to evolve in response. For single allele-multiple individuals, conflicts can extend across individuals that share an allele. Females that lack Neu5Gc raise antibodies against it. Males that lack Neu5Gc have higher rates of fertilization, and females have lower rates (14). Individual-specific regulation could resolve these conflicts. For multiple genes-single individual, selfish alleles can bias reproduction in their favor at the cost of individual reproduction, causing conflict with other genes in the genome. Mutant PMM2 alleles are passed to children more often than expected but increase the risk of congenital disorders of glycosylation (79). Other genes are selected to suppress the selfish allele, often by modification of chromosomal recombination and linkage. For multiple genes-multiple individuals, molecular markers of self cause cells to direct benefits toward identical genetic relatives, but they can be exploited by pathogen mimics. Co-evolution is a common outcome, as hosts develop more reliable markers of self, and pathogens develop more effective molecular mimics (8, 86).