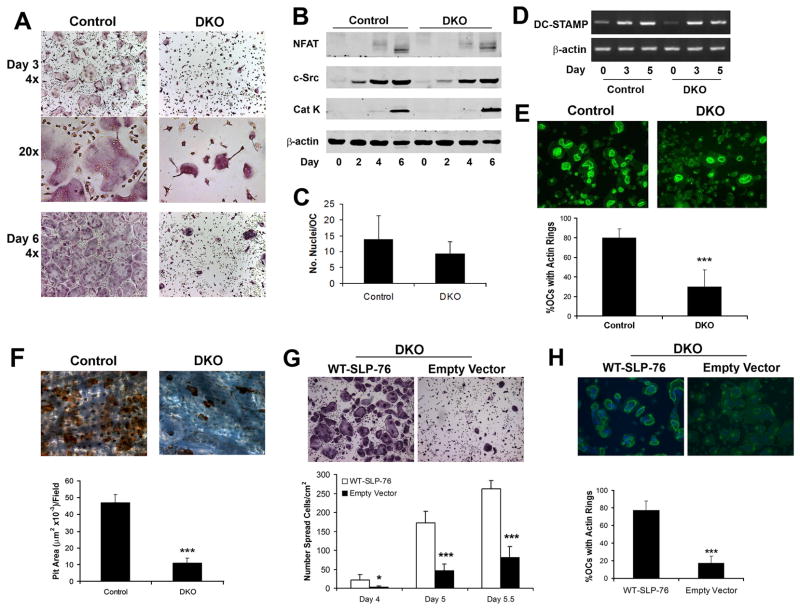

Figure 3. DKO OCs normally differentiate but are dysfunctional.

(A–B) Control (SLP-76+/− BLNK−/−) and DKO BMMs were cultured in M-CSF and RANKL, with time, fixed and (A) stained for TRAP activity (top and bottom panels, 40x, middle panel, 200x) or (B) immunoblotted for c-Src, NF-AT1c and cleaved cathepsin K (Cat K) as markers of OC differentiation. β-actin serves as loading control. (C) The number of nuclei per OC was quantified in day 5 TRAP stained cultures. (D) DKO and control BMMs were cultured in M-CSF and RANKL, with time. DC-STAMP mRNA was assessed by RT-PCR. Actin serves as loading control. (E, F) Control and DKO BMMs were cultured on bone in RANKL and M-CSF for five days. (E) The cells were fixed and labeled with FITC-phalloidin to visualize actin rings or (F) removed and the resorptive pits stained with WGA-peroxidase-conjugated lectin (200x). Resorptive area per field was histomophometrically determined. (G, H) DKO BMMs were transduced with WT-SLP-76 or empty vector. Following selection with blasticidin the transduced cells were plated on (G) plastic or (H) bone in M-CSF and RANKL. Five days later, the number of (G) spread OCs and (H) the percentage of OCs exhibiting actin rings were determined. (*p<0.05 and ***p<0.001)