Abstract

Mature dendritic cells (DC), activated lymphocytes, mononuclear cells and neutrophils express CD83, a surface protein apparently necessary for effective DC-mediated activation of naïve T-cells and T-helper cells, thymic T-cell maturation and the regulation of B-cell activation and homeostasis. Although a defined ligand of CD83 remains elusive, the multiple cellular subsets expressing CD83, as well as its numerous potential implications in immunological processes suggest that CD83 plays an important regulatory role in the mammalian immune system. Lately, nucleocytoplasmic translocation of CD83 mRNA was shown to be mediated by direct interaction between the shuttle protein HuR and a novel post-transcriptional regulatory element (PRE) located in the CD83 transcript’s coding region. Interestingly, this interaction commits the CD83 mRNA to efficient nuclear export through the CRM1 protein translocation pathway. More recently, the cellular phosphoprotein and HuR ligand ANP32B (APRIL) was demonstrated to be directly involved in this intracellular transport process by linking the CD83 mRNA:HuR ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with the CRM1 export receptor. Casein kinase II regulates this process by phosphorylating ANP32B. Here, we identify another RNA binding protein, AUF1 (hnRNP D) that directly interacts with CD83 PRE. Unlike HuR:PRE binding, this interaction has no impact on intracellular trafficking of CD83 mRNA-containing complexes; but it does regulate translation of CD83 mRNA. Thus, our data shed more light on the complex process of post-transcriptional regulation of CD83 expression. Interfering with this process may provide a novel strategy for inhibiting CD83, and thereby cellular immune activation.

INTRODUCTION

The transmembrane glycoprotein CD83 belongs to the Ig-superfamily and was shown to be highly expressed on mature dendritic cells (DC) (1–4), and moderately expressed on activated B and T lymphocytes (5–7), macrophages (8,9) and neutrophils (10). Thus, the CD83 protein serves as a surface marker for fully matured DC (2,11). Although its exact function is still unknown (12), multiple independent findings suggested that CD83 plays a crucial role in regulating several immune responses, such as thymic T-cell development (13,14), activation of T lymphocytes by DC (3,4) and several important functions in B lymphocyte biology (15).

Besides the expression of membrane-bound CD83, which is strongly upregulated during DC maturation, soluble forms of CD83 generated by alternative splicing (16) are found in the supernatants of DC and B cells (17) and at elevated levels in the serum of patients suffering from certain haematological malignancies or from rheumatoid arthritis (18). Interestingly, soluble CD83 completely abrogates DC-mediated allogenic T-cell activation in vitro and in vivo, a process that interferes with the development of autoimmune disorders or the rejection of allografts in several mice models (19–23).

CD83, therefore, seems to be an important player in regulating the adoptive immune response. However, despite intense research during the past decade, neither a defined CD83 receptor or CD83 ligand nor the respective signal transduction pathways involved have been elucidated. Nevertheless, CD83 seems to orchestrate a multitude of functions on various immune cells, for example, mediating the activation of naïve CD4+ T cells and CD8+ cells by DC (4,24–26), the thymic maturation of CD4+ single positive lymphocytes (14) and the activation, as well as homoeostasis of B lymphocytes in mice (15).

For these reasons, it was of particular interest to investigate the regulation of CD83 expression in more detail, at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level (27,28). Initially, Kruse et al. (28) provided evidence that the CD83 transcript is transported from the site of transcription in the nucleus to the cytoplasmic site of translation through an unexpected and uncommon route, engaging the nuclear export receptor CRM1. This was in strong contrast to the established notion that metazoan mRNAs are transported through the NXF1/TAP nuclear export pathway [for reviews on nuclear mRNA export see (29,30)]. A subsequent systematic analysis of potential CRM1-regulated mRNAs then demonstrated that a small subset of cellular transcripts, including the CD83 mRNA, are indeed transported across the nuclear envelope by CRM1 in activated T lymphocytes (31). This unusual export of CD83 mRNA was subsequently confirmed in independent studies (7,32,33).

CRM1 is the major nuclear export receptor for proteins, interacting with their leucine-rich nuclear export signals (NES), it is responsible for the nucleocytoplasmic translocation of a large variety of proteins and non-coding RNAs in a Ran-GTP dependent manner (34,35). Interestingly, a detailed analysis of the CD83 transcript revealed a highly structured cis-active RNA element located in the coding region of this mRNA, called the post-transcriptional regulatory element (PRE), which serves as a binding site for the cellular shuttling protein HuR (32).

The human HuR protein is a ubiquitously expressed member of a family of RNA-binding proteins, and it is related to the Drosophila ELAV (embryonic lethal abnormal vision) protein (36–39). HuR is a multifunctional regulator involved in the post-transcriptional processing of specific mRNA subsets by affecting their stability, transport or translation [reviewed in (40–42)]. HuR is mostly known for stabilizing otherwise highly unstable early response gene mRNAs (ERG) by binding to so-called AU-rich elements (AREs), which are commonly located in the untranslated regions of these ERG transcripts (43).

However, HuR binding to the coding region PRE in CD83 mRNA does not affect the stability of this message, but commits this mRNA to CRM1-mediated nuclear export (32–34). As HuR itself lacks a binding site for CRM1 (i.e. an NES), the NES-containing adaptor ANP32B, also called APRIL, connects the HuR:CD83 mRNA complex to CRM1 (44). This shuttling capacity of ANP32B is regulated by phosphorylation of its threonine-244 by casein kinase II (45).

Besides HuR, a number of ARE-binding proteins that have various impacts on the post-transcriptional processing of transcripts have been described previously (46). One cellular protein binding to ARE is AUF1, which has been reported to oppose the function of HuR in the post-transcriptional processing of ERG-mRNAs (47–49). AUF1, also called hnRNP D, is expressed in four isoforms, p37, p40, p42 and p45, by alternative splicing of a single precursor mRNA (50,51). The majority of cell culture studies correlated the overexpression of AUF1 with rapid degradation of ARE-containing mRNAs (51–55). Consequently, knock-down of AUF1 in a mouse model provoked endotoxic shock because of the failure to degrade ARE-containing pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNAs, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α transcripts (56).

The fact that both, AUF1 and HuR, bind to AREs prompted us to investigate whether AUF1, like HuR (32), also interacts with the CD83 transcript. Here, we identified AUF1 as a potent binding partner of the CD83 mRNA PRE. Furthermore, we analysed the impact of this interaction on the fate of CD83 mRNA by various experimental approaches and identified AUF1 as a pivotal regulator of CD83 mRNA translation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular clones

The plasmids pBC12/CMV/CAT, pBC12/CMV/luc, p3CD83-PRE (nucleotides 466–615), p3TNF-α-ARE, pGEM-rev response element (RRE), p3CD83PREΔSubL1 (CD83 coding sequence (CDS) deletion, nucleotides 498–537), p3CD83PREΔSubL2 (CD83 CDS deletion, nucleotides 543–555), p3CD83ΔSubL3 (CD83 CDS deletion, nucleotides 561–594), p3 untranslated region (UTR)-CD83, p3UTR-CD83ΔSubL1-3 (CD83 CDS deletion, nucleotides 498–594), pGAPDH and pUHC-UTR-CD83 were published previously (32,33). The reporter construct pBC12/CMV/luc/PRE is identical with the vector pBC12/CMV/luc/SL2 reported earlier (32).

The expression plasmids used for purifying the GST-fusion proteins, pGex-AUF1p37, pGex-AUF1p40, pGex-AUF1p42 and pGex-AUF1p45 were constructed by ligating the respective polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-generated AUF1-derived fragments between the BamHI and XhoI site of the vector pGex-5X-1 (Pharmacia Biotech). Likewise, the eukaryotic expression vectors pBC12/CMV-AUF1p37, pBC12/CMV-AUF1p40, pBC12/CMV-AUF1p42 and pBC12/CMV-AUF1p45 were constructed by ligating the respective AUF1 fragments omitting stop-codons in frame with sequences encoding the FLAG-tag between the BamHI and XbaI site of the pBC12/CMV vector (57).

For knock-down studies, the lentiviral vectors pLKO.1-puro-AUF1#1, pLKO.1-puro-AUF1#2 and pLKO.1-puro-SD were obtained from Sigma (Mission™ shRNA) encoding shRNA targeting the following sequences: 5′-TCGAAGGAACAATATCAGCAA-3′ (siAUF#1); 5′-AGAGTGGTTATGGGAAGGTAT-3′ (siAUF#2); 5′-CGTACGCGGAATACTTCGAAA-3′ (scrambled duplex, SD).

Protein purifications and RNA gel shift assays

GST fusion proteins were expressed in E scherichia coli BL21 and were purified from crude extracts by affinity chromatography on glutathione–Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia) as described previously (58). RNA gel-retardation assays were performed using in vitro-transcribed [32P]-labelled CD83-derived probes, MS2 competitor RNA and GST fusion proteins as described in detail (59), except that RNA:protein complexes were separated on 4 or 6% native polyacrylamide gels.

In vitro transcription

Labelled and non-labelled RNA was obtained by in vitro transcription with or without [α-32P] UTP (Hartmann Analytic GmbH) using a commercial T7 RNA polymerase-based kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega).

Cell culture

The cell line COS7 (ATCC CRL-1651) and HeLa-tTA (60), which constitutively expresses a Tet repressor-VP16 transactivator fusion protein, were maintained as previously described (61,62). The mononuclear cell line MonoMac6 (63) was cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% of fetal calf serum (FCS). The cells were activated by serum depletion for 12 h and by addition of 10% serum for 3 h, followed by addition of 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and 1 µM of ionomycin (both from Sigma) for up to additional 3.5 h before further analysis.

For analysis of CD83 RNA synthesis and subcellular distribution, 2.5 × 105 COS7 cells were transfected with 250 ng of either p3UTR-CD83 or p3UTR-CD83ΔSubL1-3 vector, using DEAE-dextran and chloroquine as previously described (32). Likewise, 750 ng of the pBC12/CMV-AUF1 expression vectors were co-transfected with 250 ng of either the p3UTR-CD83 or p3UTR-CD83ΔSubL1-3 vector. For analyses of RNA stability, the transcriptional pulsing strategy was performed as previously described in detail (32).

For analysis of AUF1-mediated reporter gene activation, COS7 cells (2.5 × 105) were co-transfected with 250 ng of either pBC12/CMV (negative control) or pBC12/CMV/AUF1 in combination with 125 ng of pBC12/CMV/CAT (internal control) and 250 ng of pBC12/CMV/luc expression vector using DEAE-dextran and chloroquine as described previously (64). At 60 h post-transfection, cell lysates were prepared, and the levels of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase activity were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Roche Applied Science). These values were subsequently used to determine the amount of cell extract to be assayed for luciferase activity using a commercially available assay system (Promega Corp.). DNA input levels were kept constant in all of these experiments by inclusion of parental pBC12/CMV vector DNA.

For transduction with lentiviral particles, the cells were spinoculated with an MOI of 1.0 and 2 µg/ml polybrene at 650 g for 30 min at ambient temperature. After 6 h of incubation at 37°C, supernatants were discarded, the cells were kept in culture and transduced cells were selected with puromycin.

RNA isolation and PCR analyses

Total cellular RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). For isolation of cytoplasmic and nuclear RNAs, 2 × 105 cells were lysed on ice for 1 min using 100 µl NP40 buffer (10 mM of HEPES–KOH pH 7.8, 10 mM of KCl, 20% of glycerol, 1 mM of DTT, 0.25% of NP40). Subsequently, the lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 470g for 5 min at 4°C. Cytoplasmic RNA was isolated from 80 µl of the supernatant using TRIzol reagent. The nuclei were washed again in 100 µl of NP40 buffer to deplete residual cytoplasmic RNA. Afterwards, the nuclear RNA was prepared by using TRIzol reagent. DNAse treatment of the RNA samples was performed. Selected RNA samples were reverse transcribed using the first strand cDNA (AMV) synthesis kit for reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Subsequently, RT products were assayed by PCR. For detection of GAPDH sequences, the following primers were used: forward, 5′-TGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGT-3′; reverse, 5′-CATGTGGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC-3′. The amplification profile involved 25 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 56°C for 1 min and primer extension at 72°C for 2 min. CD83 mRNAs were detected by using the following primer pairs: forward, 5 GGTGAAGGTGGCTTGCTCCGAAG-3′; reverse, 5′-GAGCCAGCAGCAGGACAATCTCC-3′. The amplification profile involved 25 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 56°C for 1 min and primer extension at 72°C for 1 min. Real-time PCR was performed in an ABI PRISM 7700 detector (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Amplification was monitored by SYBR green fluorescence. Standard curves were derived by serial dilution of p3UTR-CD83 and pGAPDH, and RNAs were normalized by amplification of GAPDH.

Protein analyses and metabolic labelling

Western blot analyses of cell extracts was performed as described previously (28) using rabbit anti-AUF1 polyclonal antiserum (kindly provided by Dr Hermann Gram, Novartis Pharma AG), anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (clone DM1A; Sigma) and anti-CD83 monoclonal antibody (clone HB15a; Acris).

For metabolic labelling, the cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline and incubated with cysteine/methionine-free medium containing 10% of dialysed FCS for 1 h. The cells were metabolically labelled for up to 1 h using 200 μCi of Tran35S-label (MP Biochemicals; 1175 Ci/mmol). Afterwards, the cultures were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline and harvested. For pulse chase experiments, the radioactive label containing culture medium was replaced by Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% of FCS for indicated periods before cell harvest. For deglycosylation of CD83, crude cellular extracts were incubated with PNGase F (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses

For flow cytometry analyses, phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD83 monoclonal antibody (clone HB15e; Pharmingen) was used. The phycoerythrin-conjugated IgG1-isotype control was obtained from Pharmingen and was run in parallel. Cell populations were analysed on a FACS-Canto™ instrument (BD Biosciences). Non-viable cells were gated-out on the basis of their light scattering properties.

RESULTS

Cytoplasmic accumulation, but diminished translation, of PRE-deleted CD83 mRNA

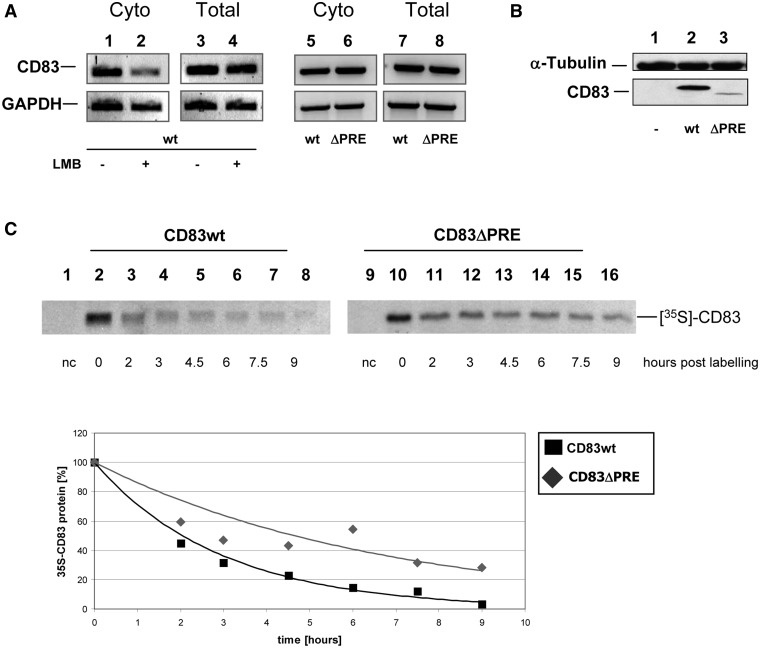

Previously, it was shown that CD83 mRNA can exit the nucleus in a CRM1-dependent manner (7,32,33). This central finding was first reconfirmed (Figure 1A; lanes 1–4). Nuclear export of CD83 mRNA depends on HuR protein binding directly to PRE, a structured RNA sequence located in the coding region of the CD83 transcript (32,33). Interestingly, mutational analysis of the CD83 mRNA demonstrated that the deletion of the PRE does not result in trapping the CD83 mRNA in the nucleus, but instead redirects this transcript from the CRM1-specific to the TAP/NXF1-specific nuclear export pathway (33). In agreement with this interpretation and as shown before, both the CD83 wild-type (wt) sequence (Figure 1A; lanes 5 and 7) and PRE-deleted (ΔPRE) CD83 mRNA (Figure 1A; lanes 6 and 8) accumulated to a comparable extent in the cytoplasm. Unexpectedly, however, western blot analysis revealed strongly reduced protein synthesis for the ΔPRE construct, suggesting that the PRE also affects subsequent translation of CD83 mRNA (Figure 1B). As demonstrated by a pulse-chase experiment, this effect is not caused by lower protein stability of the ΔPRE construct (Figure 1C). In sharp contrast to the steady state levels, the half-life of the CD83ΔPRE protein seems to be increased (t 1/2: ∼4.6 h) as compared with the wt protein (t 1/2: ∼2.1 h) (Figure 1C; lower panel).

Figure 1.

CD83 mRNA with a PRE deletion is transcribed and translocated into the cytoplasm, but is translated inefficiently. (A) Full length CD83 (lanes 1–4, 5 and 7) or a CD83ΔPRE mutant construct (lanes 6 and 8) were transfected into COS7 cells. Ten nanomolars of leptomycin B was added to samples 2 and 4. Total (lanes 3, 4, 7, 8) and cytoplasmic RNA (lanes 1, 2, 5, 6) was harvested 48 h post-transfection and was analysed by RT-PCR. (B) COS7 cells transfected as described in (A) were harvested 48 h post-transfection, crude protein extracts were prepared and subjected to western blot analysis (lane 1: mock control, lane 2: CD83 wt, lane 3: CD83ΔPRE). (C) COS7 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing complete CD83 cDNA or a derivative thereof lacking the PRE sequence (CD83ΔPRE). Twenty-four hours post–transfection, de novo synthesized proteins were labelled with a 35S-translabel pulse (1 h). For chase, cell cultures were maintained in label-free medium for the indicated periods. Crude extracts were subjected to CD83 immunoprecipitation followed by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). Protein stabilities were quantified by phosphorimaging (lane 1/9: negative control; lane 2–8: CD83 wt; lane 10–16: CD83ΔPRE; lanes 2 and 10: newly synthesized CD83 protein variants; residual lanes: indicated time points post labelling). Lower panel: quantification of relative CD83 protein levels over time for CD83 wt (black square) or for CD83ΔPRE (grey rhombus).

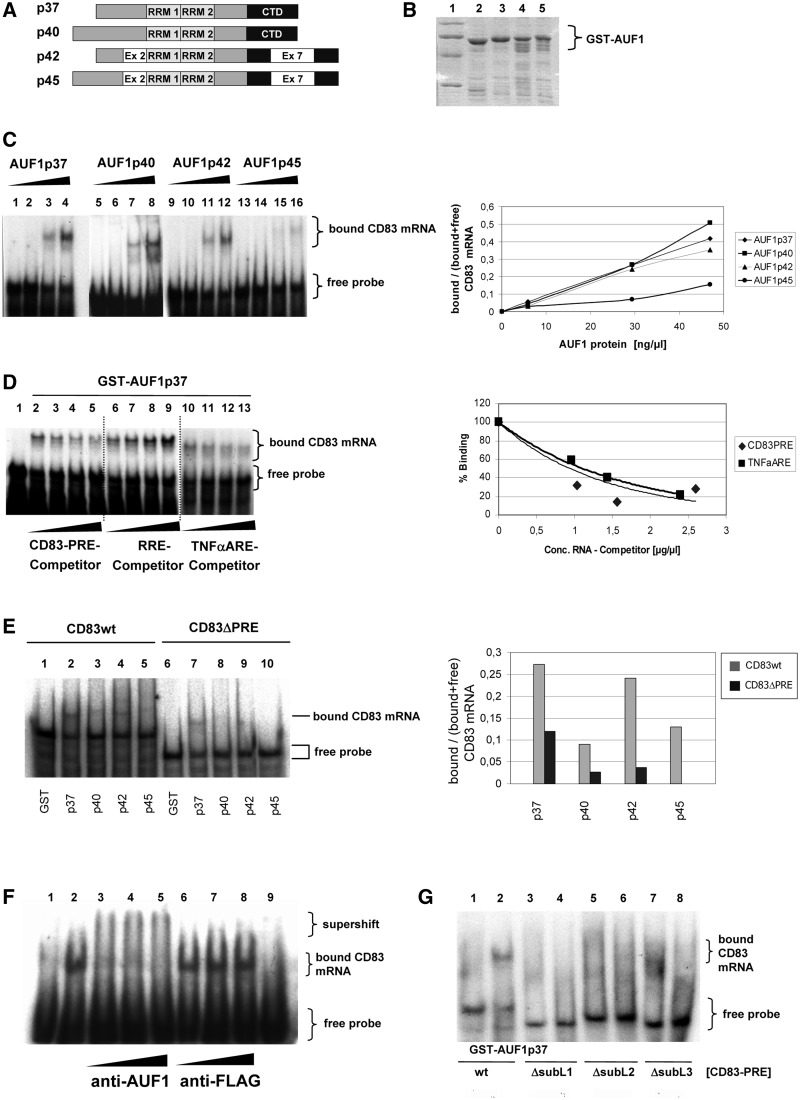

Direct binding of AUF1 isoforms to CD83 PRE RNA

Considering that the ARE-binding protein AUF1 (hnRNP D) is known to regulate the translation of MYC mRNA by directly binding to its ARE (65), we speculated that AUF1 may also have a functional role in the translation of CD83 mRNA. We, therefore, expressed all four known AUF1 isoforms (Figure 2A), p37, p40, p42 and p45 (49–51), as GST-fusions in E. coli, purified them (Figure 2B) and analysed them for CD83 PRE RNA binding using RNA gel-retardation assays. These experiments revealed that all isoforms of AUF1 indeed bind to CD83 PRE, although the p45 isoform displayed significantly reduced binding activity (Figure 2C). Quantification of the experiment (Figure 2C; right panel) confirmed comparable binding of the three small AUF1 isoforms to CD83 PRE RNA, but a reduced binding affinity in case of AUF1p45 in these in vitro binding studies. In control experiments, the addition of unlabelled competitor RNA indicated strong binding specificity by the AUF1p37 protein (Figure 2D). Clearly, the homologous CD83 PRE RNA (lanes 2–5), as well as the heterologous TNF-α ARE RNA (lanes 10–13), an established target of AUF1 [reviewed in (49,66,67)], competed with the 32P-labelled PRE probe for AUF1 binding. In sharp contrast, another highly structured RNA element, the HIV-1 RRE (68), did not compete (lanes 6–9). Quantification of PRE- and ARE-binding indicated comparable AUF1 binding affinities (Figure 2D; right panel). To analyse whether the PRE sequence is a unique AUF1 binding site in CD83 mRNA, binding studies were performed, in which the PRE sequence was deleted (Figure 2E). As shown, PRE deletion prevented the binding of the p40, p42 and p45 isoforms. However, some residual binding of AUF1p37 (∼30%) was detected in this in vitro analysis. The binding affinity was lower when compared with the binding of the PRE-containing wt transcript (Supplementary Figure S2) and, importantly, binding did not result in an activity as analysed later in the text (Figures 3–5).

Figure 2.

All isoforms of AUF1 bind specifically to CD83-PRE RNA. (A) Schematic depiction of AUF1 isoforms. (B) GST-AUF1 isoforms were expressed in E. coli, purified and analysed by Coomassie stained SDS–PAGE. Lane 1: marker; lane 2: GST-AUF1p37; lane 3: GST-AUF1p40; lane 4: GST-AUF1p42; lane 5: GST-AUF1p45. (C) CD83 PRE RNA was incubated with increasing amounts of the indicated AUF1 isoforms (lanes 1, 5, 9 and 13: 800 ng GST; lanes 2–4, 6–8, 10–12 and 14–16: 100–800 ng of recombinant GST-tagged AUF1 protein). Binding of the proteins was evaluated by RNA gel shift experiments. Right panel: quantification of the gel shift experiment by densitometry. The relation of complexed CD83 mRNA to total CD83 mRNA (bound and free RNA) was plotted against the AUF1 protein concentration as a measure for binding efficiency. (D) Five hundred nanograms of GST-AUF1p37 protein (lanes 2–13) was incubated with radiolabelled CD83 PRE RNA plus increasing amounts of non-labelled competitor RNA. Binding of AUF1p37 to radioactive CD83 PRE RNA was measured as aforementioned (lane 1: 500 ng GST; lanes 2, 6, 10: no competitor RNA; lanes 3–5: CD83 PRE RNA; lanes 7–9: HIV1-RRE RNA; lanes 11–13: TNF-α ARE RNA: each 1-, 2- and 3-fold excess). Right panel: radioactive signals from the shifted labelled CD83 PRE RNA were quantified by phosphorimaging and plotted as binding curves. (E) Thousand nanograms of indicated AUF1-proteins were incubated with CD83 wt mRNA (full length) or CD83ΔPRE mRNA. Complex formation was analysed by gel shift experiment. Lanes 1 and 6: GST-control, residual lanes indicated GST-AUF1 fusion proteins and indicated mRNA binding substrates. (F) Thousand nanograms of GST-AUF1p37 protein was incubated with radiolabelled CD83 PRE RNA (lanes 2–8). Increasing amounts of AUF1-specific antibody or non-specific antibody (anti-FLAG, Sigma) (500–1500 ng each) were added to the reactions. RNA gel shift analyses were performed to detect the binding and supershift of the protein:RNA complexes (lane 1: 1000 ng GST; lane 2: no antibody; lanes 3–5: anti-AUF1 antibody; lanes 6–8: anti-FLAG antibody; lane 9: only anti-AUF1 antibody without AUF1). (G) Radiolabelled CD83 PRE RNA (lanes 1 and 2), and single subloop deletions CD83 PRE ΔSubL1 (lanes 3 and 4); CD83 PRE ΔSubL2 (lanes 5 and 6) and CD83 PRE ΔSubL3 (lanes 7 and 8) were incubated with 1000 ng GST or 1000 ng GST-AUF1p37 as indicated (−/+). RNA gel shift analysis was performed to indicate the binding capacity.

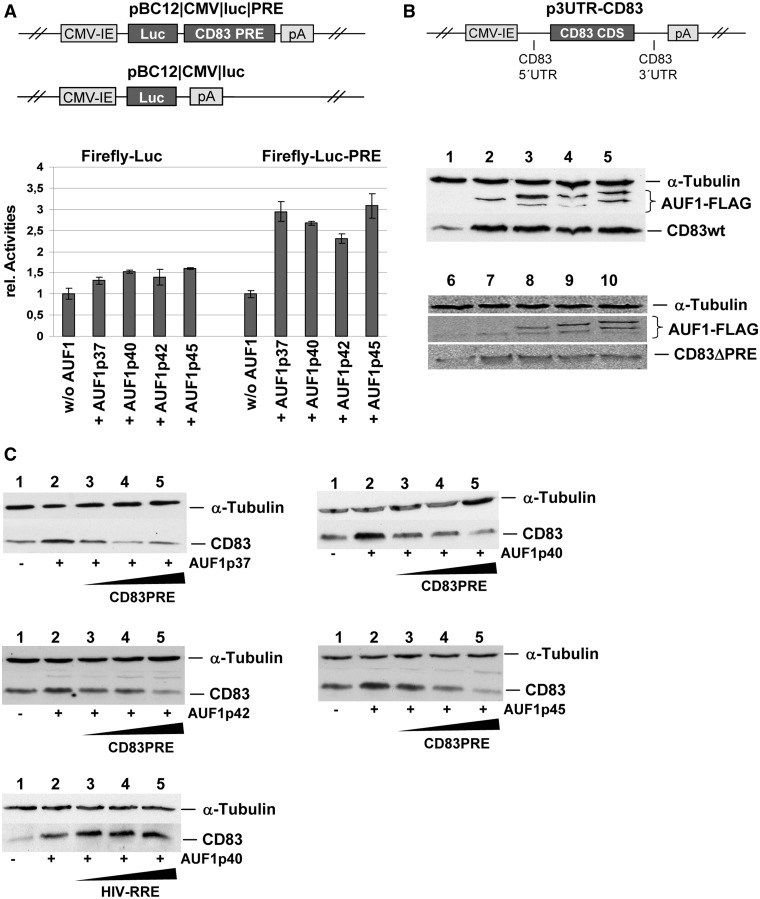

Figure 3.

Overexpression of all AUF1 isoforms enhances exogenous CD83 expression in a PRE-dependent manner. (A) COS7 cells were transiently transfected with reporter constructs encoding firefly luciferase or a firefly luciferase-PRE fusion together with indicated AUF1-isoforms. For internal control purposes, a vector encoding chloramphenicol transferase (CAT) driven by a CMV-IE promoter was co-transfected. Forty-eight hours post–transfection, crude extracts were prepared, and CAT as well as luciferase activities were analysed. Relative CAT-graded luciferase activities are depicted. (B) COS7 cells were transfected with a vector encoding complete CD83 wt cDNA or CD83ΔPRE cDNA and were co-transfected with eukaryotic expression vectors encoding FLAG-tagged AUF1-isoforms. Forty-eight hours post–transfection, crude extracts were subjected to western blot analyses detecting α-tubulin, AUF1 and CD83 (upper part: CD83 wt; lower part: CD83ΔPRE; lane 1/6: without AUF1; lane 2/7: AUF1p37; lane 3/8: AUF1-p40; lane 4/9: AUF1p42; lane 5/10: AUF1p45). (C) COS7 cells were co-transfected with a vector encoding the indicated AUF1-isoforms, a vector encoding full length CD83 cDNA, as well as with increasing amounts of a vector encoding CD83 PRE RNA (1-, 2- and 3-fold excess). As a control, HIV-1-RRE RNA was transfected instead of CD83 PRE RNA. Forty-eight hours after transfection, crude extracts were analysed by western blot analyses, detecting α-tubulin and CD83 (in each panel: lane 1: without AUF1; lane 2: indicated AUF1 isoform; lanes 3–5: isoform of AUF1 and increasing amounts of competitor RNA).

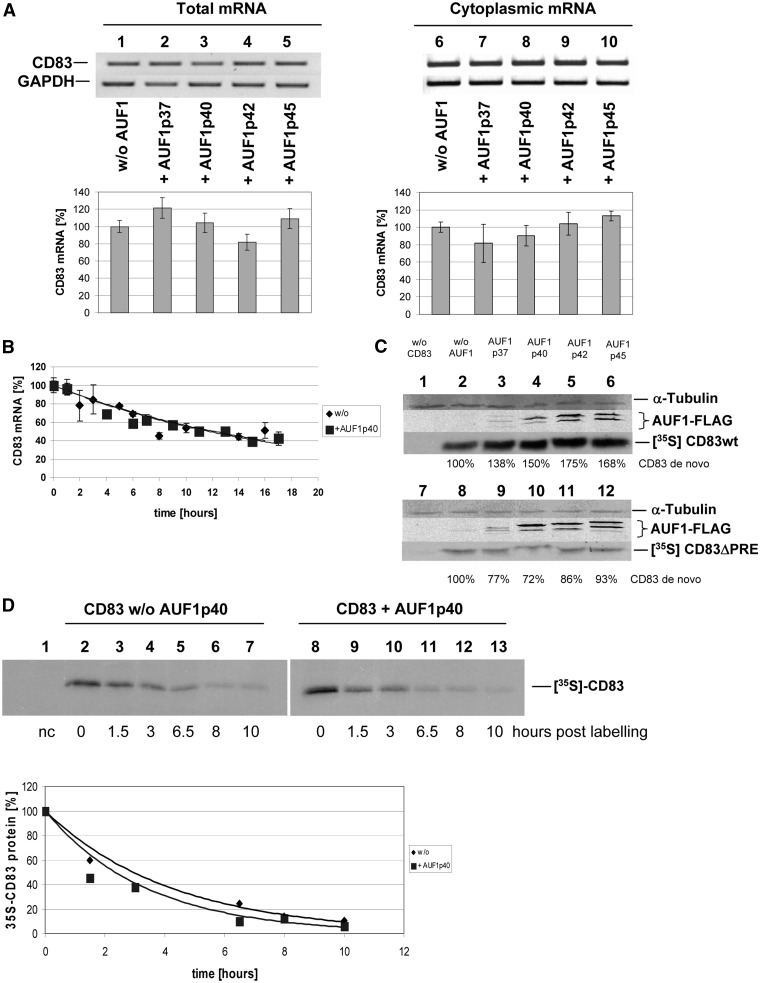

Figure 4.

AUF1 increases CD83 expression not by altering CD83 mRNA distribution or stability, but by enhancing de novo protein synthesis. (A) COS7 cells were transiently transfected with a CD83 expression construct and were co-transfected with vectors encoding for the indicated AUF1-isoforms. Total and cytoplasmic RNAs were prepared and subjected to PCR analyses (top panels: lanes 1–5: total RNA; lanes 6–10: cytoplasmic RNA; lanes 1 and 6: without AUF1; remaining lanes with indicated AUF1-isoforms; lower panels: qPCR quantification of the CD83 mRNA levels detected in the top panels, normalized to GAPDH levels). (B) HeLa-tTA cells were transfected with a construct encoding inducible CD83 cDNA and were co-transfected with a vector encoding AUF1p40 or a parental vector for control. After a transcriptional pulse, a time course was performed to isolate residual CD83 mRNA and calculate the half-life of CD83 transcripts by quantitative real time PCR. GAPDH-normalized CD83 mRNA levels are depicted. (C) COS7 cells were transfected with a vector encoding for complete CD83 wt cDNA or CD83ΔPRE cDNA and were co-transfected with eukaryotic expression vectors encoding for FLAG-tagged AUF1-isoforms. Twenty-four hours post–transfection, de novo synthesized proteins were labelled with a 35S-translabel pulse (1 h), crude extracts were subjected to CD83 immunoprecipitation followed by SDS–PAGE. Precipitated CD83 protein was quantified using a phosphorimager and the percentage values indicated in the figure (upper part: CD83 wt; lower part: CD83ΔPRE; lane 1/7: negative control; lane 2/8: without AUF1; lanes 3–6 and 9–12: AUF1-isoforms). (D) Co-transfection of CD83 and AUF1p40 expression vectors and metabolic labelling were performed as described in (C). For chase, cell cultures were maintained in label-free medium for the indicated periods. Protein stabilities were quantified by phosphorimaging (lane 1: negative control; lane 2–7: no AUF1 overexpression; lane 8–13: AUF1p40 overexpression; lanes 2 and 8: newly synthesized CD83 protein; residual lanes: indicated time points post labelling). Lower panel: relative CD83 protein levels over time reveal similar half-lives with (black square) or without (grey rhombus) AUF1p40 overexpression.

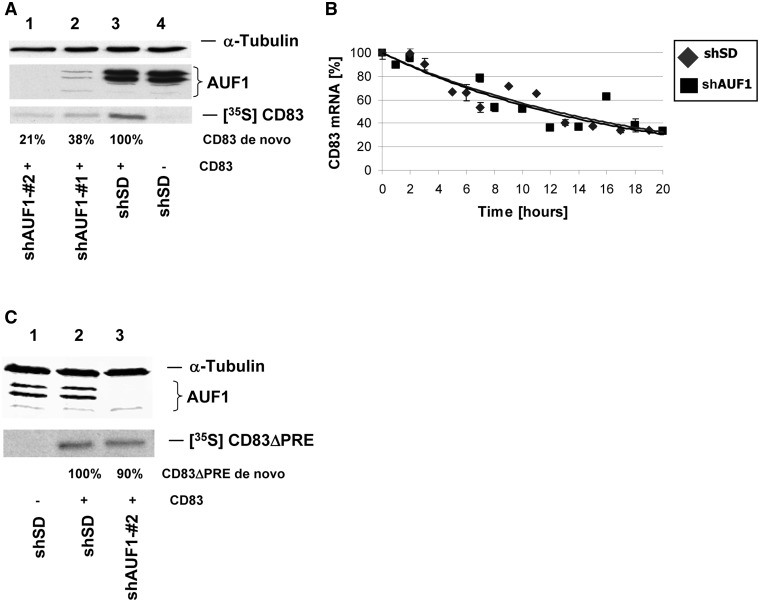

Figure 5.

siRNA mediated knock-down of AUF1 reduces CD83 expression in a post-transcriptional manner without affecting mRNA stability. (A) COS7 cells were stably transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding siRNA directed against AUF1. Two weeks after transduction, these cells were transiently transfected with CD83 expression vectors. Forty-eight hours after transfection, metabolic labelling of newly synthesized proteins was performed, crude extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis, detecting α-tubulin, AUF1 and the respective de novo synthesized CD83 proteins [left panel: lane 1: CD83 and AUFsiRNA#2; lane 2: CD83 and AUFsiRNA#1; lane 3: CD83 and SD control siRNA; lane 4: SD control siRNA without CD83; CD83 de novo expression quantities are indicated]. (B) HeLa-tTA cells were stably transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding control siRNA (shSD) or shRNA directed against AUF1. Two weeks after transduction, the cells were transfected with a construct encoding inducible CD83 cDNA. After a transcriptional pulse, a time course was performed to isolate residual CD83 mRNA and calculate the half-life of CD83 transcripts by real-time PCR. GAPDH-normalized CD83 mRNA levels are plotted against time. (C) Stably transduced COS7 cells with lentiviral vectors encoding shRNA directed against AUF1 or shSD for control were transfected with an expression vector encoding CD83ΔPRE cDNA. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were treated as described in (A), and de novo synthesized CD83ΔPRE protein was quantified (lane 1: without CD83; lane2: shSD control with CD83ΔPRE; lane 3: shAUF1 with CD83ΔPRE).

Furthermore, supershift assays showed that adding increasing amounts of AUF1-specific antibody to the binding reaction resulted in higher molecular weight complexes (Figure 2F; lanes 3–5), whereas non-specific antibody did not (lanes 6–8).

Next, when we analysed previously described CD83 PRE deletion mutants (33), we found that the entire CD83 mRNA PRE structure is necessary for interaction with AUF1. Although AUF1p37 binds to wt CD83 mRNA, as measured in RNA gel shift analyses, the depletion of single subloops of PRE abolished this binding completely (Figure 2G).

Overexpression of AUF1 enhances CD83 expression in a PRE-dependent manner

To investigate potential effects of AUF1 interacting with CD83 mRNA, reporter constructs, encoding either luciferase alone or luciferase with the CD83 PRE located in its 3′-UTR (i.e. pBC12/CMV/luc/PRE; Figure 3A), were transiently co-transfected together with each AUF1 isoform into COS7 cells. Subsequently, monitoring luciferase expression revealed increased reporter activities on AUF1 overexpression, an effect that was exclusively observed with the PRE-containing reporter construct (Figure 3A; lower panel). Cells were then co-transfected with a plasmid expressing the wt CD83 cDNA flanked by the entire homologous 5′- and 3′-UTR (p3UTR-CD83; Figure 3B) together with expression vectors encoding FLAG-tagged versions of the AUF1 isoforms. Detection of AUF1 and CD83 proteins by western blot analyses revealed increased CD83 protein levels in AUF1 co-expressing cells (Figure 3B; middle panel). The lower in vitro binding of AUF1p45 to CD83 mRNA (Figure 2) did not result in quantitatively different CD83 protein expression when compared with the effect caused by the other AUF1 isoforms (Figure 3B; middle panel). This type of functional analysis was also performed with the CD83ΔPRE mutant RNA. Clearly, the increase in CD83 wt protein level because of AUF1 overexpression was not observed when this deletion mutant was analysed (Figure 3B; lower panel).

Strikingly, when the co-transfection experiments in Figure 3B included increasing amounts of CD83 PRE-expressing vector DNA, CD83 expression reverted to levels without AUF1 overexpression (Figure 3C), suggesting a competitive quenching effect of CD83 PRE. In contrast, overexpression of the unrelated HIV-1 RRE did not affect CD83 expression. These results argue that specific post-transcriptional regulation of CD83 expression is indeed AUF1- and PRE-dependent.

AUF1 overexpression does not affect intracellular distribution or stability of CD83 mRNA, but enhances CD83 protein synthesis

To investigate how AUF1 affects CD83 expression in more detail, we next analysed total and cytoplasmic levels of CD83 mRNA in transfected COS7 cells. Neither total CD83 mRNA nor cytoplasmic CD83 mRNA amounts were significantly affected by overexpression of the various AUF1 isoforms (Figure 4A). These results were further supported by using a transcriptional pulsing strategy (69,70); HeLa-tTA cells (60) were co-transfected with the pUHC-UTR-CD83 plasmid, expressing the CD83 coding sequence and the wt UTRs (Figure 3B) under the control of a tetracycline-sensitive transactivator-responsive promoter, and the AUF1p40 expression vector or respective parental vector for control. On doxycycline-induced transcriptional shut-off, an RNA-isolation time course was performed, and CD83 transcripts were quantified by real-time PCR. CD83 mRNAs displayed comparable stabilities in control and AUF1-overexpressing cells (Figure 4B).

Taken together, these findings suggest that an AUF1-effect on CD83 mRNA processing occurs after this transcript has reached the cytoplasm. This notion was further supported when CD83 protein synthesis was measured by metabolic labelling of transfected cell cultures in the presence or absence of the various AUF1 isoforms. COS7 cells were transiently transfected with CD83 and AUF1 expression plasmids and were treated with 35S-labelled methionine and cysteine for a short period. Subsequently, newly synthesized CD83 protein was detected by CD83-specific immunoprecipitation analysis. Co-expression of AUF1 clearly enhanced the rate of de novo CD83 protein synthesis (Figure 4C; upper panel), indicating a direct AUF1 effect on the translation of CD83 mRNA. This effect was not observed when the CD83ΔPRE mutant as analysed in this type of experiment (Figure 4C; lower panel). In addition, the impact of AUF1 overexpression on CD83 protein stability was analysed by pulse-chase experiments. The initial increase in newly synthesized CD83 protein mediated by AUF1p40 overexpression was confirmed (Figure 4D; compare lanes 2 and 8). However, as the half-life of CD83 in the absence or presence of overexpressed AUF1, quantified by phosphorimaging, was 2.9 h (without AUF1 overexpression) or 2.4 h (with AUF1 overexpression) (Figure 4D; lower panel); AUF1 had no significant impact on the degradation of CD83 protein.

Silencing endogenous AUF1 impairs CD83 expression in a post-transcriptional fashion

To further evaluate the impact of AUF1 on CD83 expression, we silenced AUF1 by RNA interference (RNAi). First, COS7 cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing two different short hairpin RNAs (shAUF1#1 and shAUF#2) directed against target sequences present in the transcript of all AUF1 isoforms. Two weeks after lentiviral transduction, the respective cultures were transiently transfected with CD83 expression plasmid (p3UTR-CD83; depicted in Figure 3B). Subsequent western blot analysis demonstrated that both lentiviral vectors strongly reduced the expression of all endogenous AUF1 proteins, as well as de novo CD83 synthesis (Figure 5A; lanes 1 and 2). These effects were not observed in control experiments with lentiviral vectors expressing SD shRNA (shSD) (Figure 5A; lanes 3 and 4). Another transcriptional pulse experiment demonstrated that silencing of AUF1 did not affect the stability of CD83 mRNA (Figure 5B), again suggesting that AUF1 proteins affect CD83 expression at the post-transcriptional level, most likely directly affecting translation. To demonstrate the requirement of the PRE sequence for this level of CD83 regulation, the same experiment was performed using the CD83ΔPRE mutant. As expected and in agreement with the previous data, deletion of the PRE from the CD83 transcript resulted in AUF1-independent CD83 translation (Figure 5C).

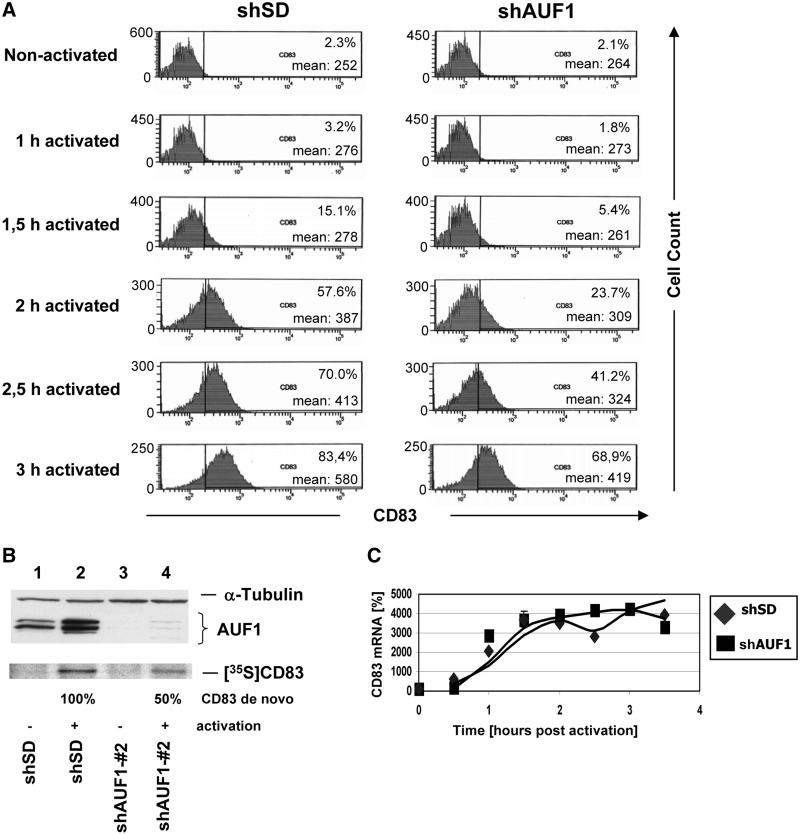

Next, the effect of AUF1 silencing on the expression of endogenous CD83 was investigated using the mononuclear cell line MonoMac6, which expresses CD83 surface protein on cellular activation with ionomycin and PMA. MonoMac6 cultures were first transduced with shAUF1#2 lentiviral particles or negative control shSD particles as before. After ionomycin/PMA activation, CD83 surface expression was monitored by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) in both cultures over time. The knock-down of AUF1 clearly resulted in attenuation of the surface expression of endogenous CD83 protein (Figure 6A). The analysis of the forward and sideward scatter profile (Supplementary Figure S1) served as an indicator of cellular maintenance. Western blot analyses confirmed effective AUF1 silencing in the shAUF1#2-transduced MonoMac6 cultures (Figure 6B; lanes 3 and 4). Furthermore, CD83-specific immunoprecipitation analysis of metabolically labelled MonoMac6 extracts demonstrated again that CD83 synthesis is strongly reduced by ∼50% in AUF1-depleted cells (Figure 6B; lower panel). As expected, mRNA quantification in the respective cell cultures by PCR revealed no significant effect of AUF1-silencing on CD83 mRNA levels (Figure 6C), mirroring the results obtained before using transiently transfected cells.

Figure 6.

Knock-down of AUF1 attenuates endogenous CD83 expression in a mononuclear cell line at the post-transcriptional level. MonoMac6 cells were stably transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding control siRNA (siSD) or AUF1-siRNA#2. Two weeks later, the cells were activated with ionomycin and PMA. Within several hours, the cells were harvested and (A) endogenous CD83 surface expression was quantified by FACS analysis (left control; right siAUF1 knock-down). (B) CD83 de novo synthesis between 1.5 and 2.5 h post-activation was measured by a transcriptional pulse experiment. The respective crude extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation, followed by SDS–PAGE and quantification by phosphorimaging. In parallel, the crude extracts were evaluated by western blot analysis of α-tubulin and AUF1 expression (lanes 1 and 2: SD siRNA controls; lanes 3 and 4: siAUF1; lane 1 and 3: no activation; lane 2 and 4: activation). (C) CD83 mRNA transcription rates were determined by isolating and reverse transcribing total RNA from cells during the time course described in (A) and (B). The respective cDNA was quantified by real time PCR, including GAPDH transcripts for evaluation. GAPDH-normalized CD83 transcript signals are plotted against time.

DISCUSSION

As CD83 seems to be an important immune regulatory molecule, it may hold great potential for therapeutic applications (13). However, before such possible clinical applications, the biology of CD83 must be investigated in more detail, particularly at the molecular level. Besides the challenge of finding a bona fide ligand of CD83 and analysing the upstream signalling pathways that affect CD83 function, detailed analysis of the post-transcriptional regulation of CD83 expression has become a major focus in recent years. Unexpectedly, this revealed that the CD83 transcript accesses an uncommon mRNA nucleocytoplasmic transport route, involving a specific cis-active CD83 RNA domain, the RNA-binding protein HuR and its adaptor ANP32B, the export receptor CRM1 and casein kinase II regulating this export process by ANP32B phosphorylation (7,28,31,32,44,45).

More recently, it has been demonstrated that deletion of the PRE from the CD83 transcript does not trap this mRNA in the nucleus, but results in it being redirected away from the CRM1 export receptor towards the standard NXF/TAP-specific cellular mRNA export pathway (33). Although the ΔPRE CD83 mRNA localizes efficiently in the cytoplasm (Figure 1A), translation of this transcript is inefficient (Figure 1B). We, therefore, hypothesized that either HuR or another PRE-binding protein may affect the translation of the CD83 transcript. It was recently reported that AUF1 regulates the translation of MYC mRNA (65), a transcript rich in AU elements (ARE). Another independent study demonstrated that AUF1 interacts with the eIF4G, poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) complex, therefore, suggesting an AUF1 function in translation during AU-rich mRNA decay (71).

Our RNA–protein interaction analyses revealed a strong and specific association between AUF1 and CD83 PRE RNA (Figure 2). However, residual low-affinity binding of the AUF1p37 isoform to CD83 mRNA lacking the PRE sequence RNA was observed (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figure S2). Whether this rather weak interaction is of any biological relevance and the location of the respective binding site in CD83 mRNA has to be investigated in future studies. As shown here, binding of the AUF1p37 isoform to ΔPRE transcripts did neither affect CD83 de novo synthesis (Figure 4C) nor the protein’s half-life (Figure 4D). One may speculate that indeed a secondary binding site for AUF1p37 exists in CD83 mRNA, thus resembling the structure of TNF-α mRNA. The stability of the TNF-α transcript is regulated by binding of AUF1 to an ARE sequence located in its 3′-UTR (49,66,67). Besides this primary binding site, a secondary constitutive decay element (CDE) was also identified in this transcript that affects the stability of TNF-α mRNA independently from the ARE (72). However, the combined results raised in the present study indicate that the regulation of CD83 translation by AUF1 proteins is mediated exclusively through the PRE sequence.

As CD83 mRNA, including the PRE, does not harbour any classical class I or II AREs (32), which could serve as an AUF1 binding site, the association seems to be structure dependent. Moreover, deletion of ARE class III-like sequences (i.e. uridine-rich patches) within the PRE had no influence on HuR binding (33), assuming a structure-dependent binding of both HuR and AUF1 to the CD83 PRE.

Interestingly, the established function of HuR and AUF1, namely regulating transcript stability [for review see (41,46,49)] is not relevant in the case of CD83 mRNA [Figures 4B and 5B (32)]. This emphasizes the importance of other HuR and AUF1 activities, such as promoting the intracellular trafficking of specific mRNAs and their translation. Indeed, the strong PRE-dependent effect of AUF1 on CD83 protein expression, revealed by either AUF1 overexpression (Figure 3) or AUF1 knock-down (Figures 5 and 6), demonstrated that AUF1 plays a role in regulating CD83 translation, independently from the specific AUF1 isoform. It is known that AUF1 isoforms can have different effects on a specific RNA (73–75). In contrast, it has also been reported that all AUF1 isoforms act in a similar manner on the stability of distinct messages (76). As shown here, the latter type of regulation also seems to be operational during translational control of CD83 mRNA by AUF1 proteins.

In a wider context, the data raised in the present and previous studies (7,28,32,33,44,45) suggest that transcripts encoding gene products required for cellular activation, such as CD83 mRNA, are exported from the nucleus through the HuR—CRM1 route. This specific export route might be more efficient, as it would only handle a small subset of functionally important transcripts (31), as opposed to the more general NXF1/TAP pathway, which mediates the nuclear export of the bulk of cellular transcripts (29,30).

AUF1 proteins apparently undergo nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, first associating in the nucleus with their mRNA target before affecting the cytoplasmic fate of these transcripts (77,78). Therefore, the nuclear recruitment of AUF1 into the CD83:HuR–RNP complex (i.e. attached to CD83 PRE) would ensure efficient CD83 protein synthesis by promoting its translation in the cytoplasm.

It is further noted that nuclear export of AUF1 p42 was recently shown to be sensitive to leptomycin B, which suggested a CRM1-dependent mechanism (79). In addition, such mechanisms would provide significant kinetic advantages with respect to rapid synthesis of gene products that are essential to mount an efficient immune response to foreign antigens.

Recently published data report the simultaneous binding of AUF1 and TIAR (T-cell internal antigen-1-related protein/TIA-1) to the ARE of ERG mRNAs (65,80). Importantly, TIAR was previously shown to bind AREs, suppressing translation of these transcripts (81). Particularly in the case of MYC RNA, AUF1 apparently fulfils the following two separate functions: it displaces ARE-bound TIAR from the MYC transcript, thereby diminishing the inhibitory effect of TIAR on translation, and it also enhances the translation process, most likely by connecting eIF4G and PABP. It is, therefore, tempting to speculate that such or similar mechanisms are also operating in the case of CD83 mRNA. Whether the CD83 PRE is also a target of TIAR remains to be investigated.

Taken together, this work expands our knowledge about the rather complex mechanism of post-transcriptional regulation of CD83 expression. The identification of AUF1 as a PRE-binding protein may provide a novel opportunity to interfere with CD83 expression, and hence, with the immunomodulatory activities of this protein.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

FUNDING

Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung [1003.033.1]; Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [CH668/1-1]; Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg and the Federal Ministry of Health. Funding for open access charge: Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg and the Federal Ministry of Health (Budget for publication costs of the Heinrich Pette Institute).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Bettina Abel for technical assistance. The authors are most grateful to Dr Hermann Gram (Novartis Pharma AG) for anti-AUF1 antiserum.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou LJ, Schwarting R, Smith HM, Tedder TF. A novel cell-surface molecule expressed by human interdigitating reticulum cells, Langerhans cells, and activated lymphocytes is a new member of the Ig superfamily. J. Immunol. 1992;149:735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou LJ, Tedder TF. Human blood dendritic cells selectively express CD83, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. J. Immunol. 1995;154:3821–3835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechmann M, Zinser E, Golka A, Steinkasserer A. Role of CD83 in the immunomodulation of dendritic cells. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2002;129:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000065883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prechtel AT, Steinkasserer A. CD83: an update on functions and prospects of the maturation marker of dendritic cells. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2007;299:59–69. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0743-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kretschmer B, Luthje K, Guse AH, Ehrlich S, Koch-Nolte F, Haag F, Fleischer B, Breloer M. CD83 modulates B cell function in vitro: increased IL-10 and reduced Ig secretion by CD83Tg B cells. PLoS One. 2007;2:e755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prazma CM, Yazawa N, Fujimoto Y, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. CD83 expression is a sensitive marker of activation required for B cell and CD4+ T cell longevity in vivo. J. Immunol. 2007;179:4550–4562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chemnitz J, Turza N, Hauber I, Steinkasserer A, Hauber J. The karyopherin CRM1 is required for dendritic cell maturation. Immunobiology. 2010;215:370–379. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao W, Lee SH, Lu J. CD83 is preformed inside monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells, but it is only stably expressed on activated dendritic cells. Biochem. J. 2005;385:85–93. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicod LP, Joudrier S, Isler P, Spiliopoulos A, Pache JC. Upregulation of CD40, CD80, CD83 or CD86 on alveolar macrophages after lung transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1067–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashiro S, Wang JM, Yang D, Gong WH, Kamohara H, Yoshimura T. Expression of CCR6 and CD83 by cytokine-activated human neutrophils. Blood. 2000;96:3958–3963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scholler N, Hayden-Ledbetter M, Dahlin A, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE, Ledbetter JA. Cutting edge: CD83 regulates the development of cellular immunity. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2599–2602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senechal B, Boruchov AM, Reagan JL, Hart DN, Young JW. Infection of mature monocyte-derived dendritic cells with human cytomegalovirus inhibits stimulation of T-cell proliferation via the release of soluble CD83. Blood. 2004;103:4207–4215. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimoto Y, Tedder TF. CD83: a regulatory molecule of the immune system with great potential for therapeutic application. J. Med. Dent. Sci. 2006;53:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto Y, Tu L, Miller AS, Bock C, Fujimoto M, Doyle C, Steeber DA, Tedder TF. CD83 expression influences CD4+ T cell development in the thymus. Cell. 2002;108:755–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00673-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breloer M, Fleischer B. CD83 regulates lymphocyte maturation, activation and homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudziak D, Nimmerjahn F, Bornkamm GW, Laux G. Alternative splicing generates putative soluble CD83 proteins that inhibit T cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6672–6676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hock BD, Kato M, McKenzie JL, Hart DN. A soluble form of CD83 is released from activated dendritic cells and B lymphocytes, and is detectable in normal human sera. Int. Immunol. 2001;13:959–967. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.7.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hock BD, Haring LF, Steinkasserer A, Taylor KG, Patton WN, McKenzie JL. The soluble form of CD83 is present at elevated levels in a number of hematological malignancies. Leuk. Res. 2004;28:237–241. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(03)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lechmann M, Krooshoop DJ, Dudziak D, Kremmer E, Kuhnt C, Figdor CG, Schuler G, Steinkasserer A. The extracellular domain of CD83 inhibits dendritic cell-mediated T cell stimulation and binds to a ligand on dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:1813–1821. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholler N, Hayden-Ledbetter M, Hellstrom KE, Hellstrom I, Ledbetter JA. CD83 is an I-type lectin adhesion receptor that binds monocytes and a subset of activated CD8+ T cells [corrected] J. Immunol. 2001;166:3865–3872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zinser E, Lechmann M, Golka A, Lutz MB, Steinkasserer A. Prevention and treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by soluble CD83. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:345–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge W, Arp J, Lian D, Liu W, Baroja ML, Jiang J, Ramcharran S, Eldeen FZ, Zinser E, Steinkasserer A, et al. Immunosuppression involving soluble CD83 induces tolerogenic dendritic cells that prevent cardiac allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2010;90:1145–1156. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181f95718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lan Z, Lian D, Liu W, Arp J, Charlton B, Ge W, Brand S, Healey D, DeBenedette M, Nicolette C, et al. Prevention of chronic renal allograft rejection by soluble CD83. Transplantation. 2010;90:1278–1285. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318200005c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1991;9:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lechmann M, Berchtold S, Hauber J, Steinkasserer A. CD83 on dendritic cells: more than just a marker for maturation. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:273–275. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berchtold S, Muhl-Zurbes P, Maczek E, Golka A, Schuler G, Steinkasserer A. Cloning and characterization of the promoter region of the human CD83 gene. Immunobiology. 2002;205:231–246. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruse M, Rosorius O, Krätzer F, Bevec D, Kuhnt C, Steinkasserer A, Schuler G, Hauber J. Inhibition of CD83 cell surface expression during dendritic cell maturation by interference with nuclear export of CD83 mRNA. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1581–1590. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohler A, Hurt E. Exporting RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:761–773. doi: 10.1038/nrm2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carmody SR, Wente SR. mRNA nuclear export at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:1933–1937. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schütz S, Chemnitz J, Spillner C, Frohme M, Hauber J, Kehlenbach RH. Stimulated expression of mRNAs in activated T cells depends on a functional CRM1 nuclear export pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prechtel AT, Chemnitz J, Schirmer S, Ehlers C, Langbein-Detsch I, Stulke J, Dabauvalle MC, Kehlenbach RH, Hauber J. Expression of CD83 is regulated by HuR via a novel cis-active coding region RNA element. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:10912–10925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pieper D, Schirmer S, Prechtel AT, Kehlenbach RH, Hauber J, Chemnitz J. Functional characterization of the HuR:CD83 mRNA interaction. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fornerod M, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Mattaj IW. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell. 1997;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hutten S, Kehlenbach RH. CRM1-mediated nuclear export: to the pore and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma WJ, Cheng S, Campbell C, Wright A, Furneaux H. Cloning and characterization of HuR, a ubiquitously expressed Elav-like protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:8144–8151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.King PH, Levine TD, Fremeau RT, Jr, Keene JD. Mammalian homologs of Drosophila ELAV localized to a neuronal subset can bind in vitro to the 3' UTR of mRNA encoding the Id transcriptional repressor. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:1943–1952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01943.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szabo A, Dalmau J, Manley G, Rosenfeld M, Wong E, Henson J, Posner JB, Furneaux HM. HuD, a paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis antigen, contains RNA-binding domains and is homologous to Elav and Sex-lethal. Cell. 1991;67:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90184-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Good PJ. A conserved family of Elav-like genes in vertebrates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:4557–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keene JD. Why is Hu where? Shuttling of early-response-gene messenger RNA subsets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2001;58:266–277. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinman MN, Lou H. Diverse molecular functions of Hu proteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:3168–3181. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakheet T, Williams BR, Khabar KS. ARED 3.0: the large and diverse AU-rich transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D111–D114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fries B, Heukeshoven J, Hauber I, Grüttner C, Stocking C, Kehlenbach RH, Hauber J, Chemnitz J. Analysis of nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of the HuR ligand APRIL and its influence on CD83 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:4504–4515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chemnitz J, Pieper D, Grüttner C, Hauber J. Phosphorylation of the HuR ligand APRIL by casein kinase 2 regulates CD83 expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:267–279. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barreau C, Paillard L, Osborne HB. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles? Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:7138–7150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brewer G. An A + U-rich element RNA-binding factor regulates c-myc mRNA stability in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:2460–2466. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W, Wagner BJ, Ehrenman K, Schaefer AW, DeMaria CT, Crater D, DeHaven K, Long L, Brewer G. Purification, characterization, and cDNA cloning of an AU-rich element RNA-binding protein, AUF1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:7652–7665. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gratacos FM, Brewer G. The role of AUF1 in regulated mRNA decay. Wiley. Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2010;1:457–473. doi: 10.1002/wrna.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner BJ, DeMaria CT, Sun Y, Wilson GM, Brewer G. Structure and genomic organization of the human AUF1 gene: alternative pre-mRNA splicing generates four protein isoforms. Genomics. 1998;48:195–202. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson GM, Brewer G. The search for trans-acting factors controlling messenger RNA decay. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1999;62:257–291. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buzby JS, Brewer G, Nugent DJ. Developmental regulation of RNA transcript destabilization by A + U-rich elements is AUF1-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33973–33978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He C, Schneider R. 14-3-3sigma is a p37 AUF1-binding protein that facilitates AUF1 transport and AU-rich mRNA decay. EMBO J. 2006;25:3823–3831. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loflin P, Chen CY, Shyu AB. Unraveling a cytoplasmic role for hnRNP D in the in vivo mRNA destabilization directed by the AU-rich element. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1884–1897. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.14.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarkar B, Xi Q, He C, Schneider RJ. Selective degradation of AU-rich mRNAs promoted by the p37 AUF1 protein isoform. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:6685–6693. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6685-6693.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu JY, Sadri N, Schneider RJ. Endotoxic shock in AUF1 knockout mice mediated by failure to degrade proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3174–3184. doi: 10.1101/gad.1467606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cullen BR. Trans-activation of human immunodeficiency virus occurs via a bimodal mechanism. Cell. 1986;46:973–982. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosorius O, Heger P, Stelz G, Hirschmann N, Hauber J, Stauber RH. Direct observation of nucleocytoplasmic transport by microinjection of GFP-tagged proteins in living cells. Biotechniques. 1999;27:350–355. doi: 10.2144/99272rr02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daly TJ, Doten RC, Rennert P, Auer M, Jaksche H, Donner A, Fisk G, Rusche JR. Biochemical characterization of binding of multiple HIV-1 Rev monomeric proteins to the Rev responsive element. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10497–10505. doi: 10.1021/bi00090a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heger P, Rosorius O, Hauber J, Stauber RH. Titration of cellular export factors, but not heteromultimerization, is the molecular mechanism of trans-dominant HTLV-1 rex mutants. Oncogene. 1999;18:4080–4090. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McKinsey TA, Chu Z, Tedder TF, Ballard DW. Transcription factor NF-kappaB regulates inducible CD83 gene expression in activated T lymphocytes. Mol. Immunol. 2000;37:783–788. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Thiel E, Futterer A, Herzog V, Wirtz A, Riethmuller G. Establishment of a human cell line (Mono Mac 6) with characteristics of mature monocytes. Int. J. Cancer. 1988;41:456–461. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910410324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cullen BR. Use of eukaryotic expression technology in the functional analysis of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:684–704. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liao B, Hu Y, Brewer G. Competitive binding of AUF1 and TIAR to MYC mRNA controls its translation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:511–518. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson GM, Sun Y, Lu H, Brewer G. Assembly of AUF1 oligomers on U-rich RNA targets by sequential dimer association. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33374–33381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilson GM, Lu J, Sutphen K, Sun Y, Huynh Y, Brewer G. Regulation of A + U-rich element-directed mRNA turnover involving reversible phosphorylation of AUF1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33029–33038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malim MH, Hauber J, Le SY, Maizel JV, Cullen BR. The HIV-1 rev trans-activator acts through a structured target sequence to activate nuclear export of unspliced viral mRNA. Nature. 1989;338:254–257. doi: 10.1038/338254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu N, Loflin P, Chen CY, Shyu AB. A broader role for AU-rich element-mediated mRNA turnover revealed by a new transcriptional pulse strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:558–565. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Loflin PT, Chen CY, Xu N, Shyu AB. Transcriptional pulsing approaches for analysis of mRNA turnover in mammalian cells. Methods. 1999;17:11–20. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu JY, Bergman N, Sadri N, Schneider RJ. Assembly of AUF1 with eIF4G-poly(A) binding protein complex suggests a translation function in AU-rich mRNA decay. RNA. 2006;12:883–893. doi: 10.1261/rna.2308106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stoecklin G, Lu M, Rattenbacher B, Moroni C. A constitutive decay element promotes tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA degradation via an AU-rich element-independent pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:3506–3515. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3506-3515.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lund N, Milev MP, Wong R, Sanmuganantham T, Woolaway K, Chabot B, Abou ES, Mouland AJ, Cochrane A. Differential effects of hnRNP D/AUF1 isoforms on HIV-1 gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3663–3675. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen TM, Hsu CH, Tsai SJ, Sun HS. AUF1 p42 isoform selectively controls both steady-state and PGE2-induced FGF9 mRNA decay. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:8061–8071. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarkar S, Sinsimer KS, Foster RL, Brewer G, Pestka S. AUF1 isoform-specific regulation of anti-inflammatory IL10 expression in monocytes. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2008;28:679–691. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pautz A, Linker K, Altenhofer S, Heil S, Schmidt N, Art J, Knauer S, Stauber R, Sadri N, Pont A, et al. Similar regulation of human inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression by different isoforms of the RNA-binding protein AUF1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:2755–2766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sarkar B, Lu JY, Schneider RJ. Nuclear import and export functions in the different isoforms of the AUF1/heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20700–20707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen CY, Xu N, Zhu W, Shyu AB. Functional dissection of hnRNP D suggests that nuclear import is required before hnRNP D can modulate mRNA turnover in the cytoplasm. RNA. 2004;10:669–680. doi: 10.1261/rna.5269304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhai B, Yang H, Mancini A, He Q, Antoniou J, Di Battista JA. Leukotriene B(4) BLT receptor signaling regulates the level and stability of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) mRNA through restricted activation of Ras/Raf/ERK/p42 AUF1 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:23568–23580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lal A, Abdelmohsen K, Pullmann R, Kawai T, Galban S, Yang X, Brewer G, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional derepression of GADD45alpha by genotoxic stress. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mazan-Mamczarz K, Lal A, Martindale JL, Kawai T, Gorospe M. Translational repression by RNA-binding protein TIAR. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:2716–2727. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2716-2727.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.