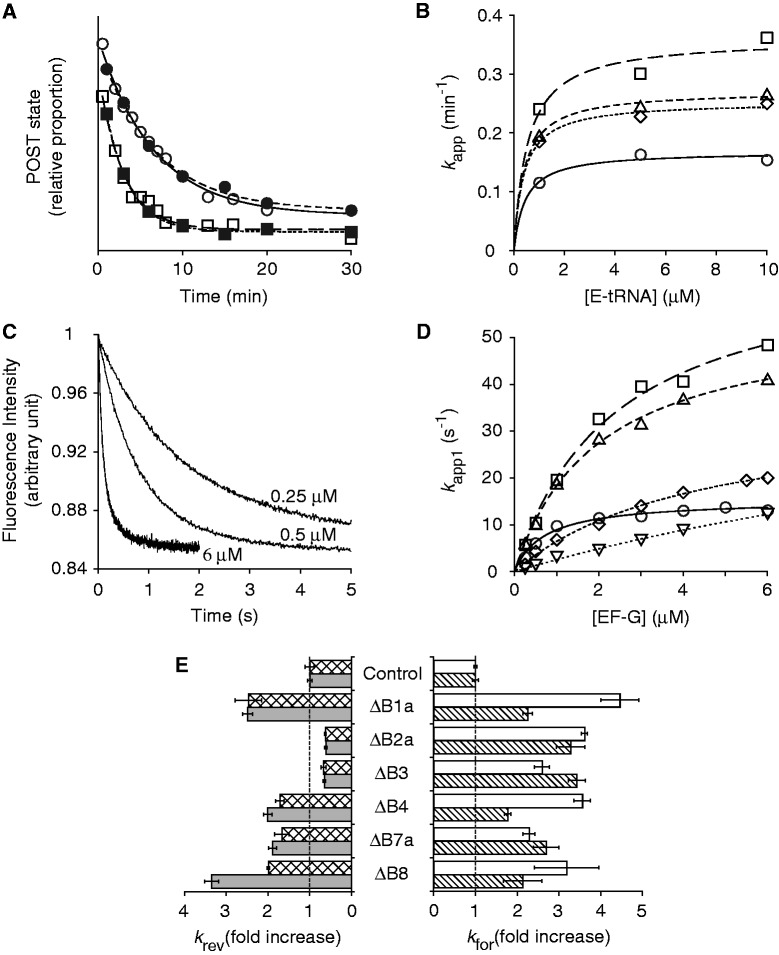

Figure 2.

Effects of bridge mutations on translocation. (A) Examples of experiments in which rates of reverse translocation in control (circles) and mutant (ΔB1a; squares) ribosomes were measured, using toeprinting (open symbols) or puromycin-reactivity (closed symbols) assays. Data were fit to a single-exponential function to obtain apparent rates. (B) Apparent rates of reverse translocation (as measured by toeprinting) plotted against E-site tRNA concentration for the control (open circles) and mutant (ΔB1a, open squares; ΔB4, open triangles; ΔB7a, open rhombus) ribosomes. Curves represent hyperbolic fits to the data. (C) Examples of fluorescence traces obtained in measuring rates of forward translocation at different concentrations of EF-G (as indicated). Data were fit to a double-exponential function to obtain apparent rates for the fast (k app1) and slow (k app2) phases. (D) Plots of k app1 versus EF-G concentration for the control (open circles) and a number of mutant ribosomes (ΔB1a, open squares; ΔB4, open triangles; ΔB7a, open rhombus; ΔB8, open inverted triangles). Data were fit to the equation k app = k for•[EF-G]/(K 1/2 + [EF-G]) to yield the parameters shown in Table 2. (E) Summary of the effects of the bridge mutations on the maximal rate of spontaneous reverse translocation [k rev; toeprinting (checkered bars), puromycin-reactivity (gray bars)] and EF-G-catalyzed forward translocation (k for1, white bars; k for2, striped bars).