Abstract

Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) inhibitors of miR-221-3p (CU-PNA-221) and miR-466l-3p (CU-PNA-466) demonstrated changes in inflammatory responses. Suppression of inflammatory signalling was unexpected and further investigation led to the identification of calmodulin as a novel target of miRNA-466l-3p. These studies demonstrate exogenous agents may suppress neuroinflammation mediated by microglial cells.

MicroRNA (miRNA) molecules are short (~20 nucleotide) RNA sequences which can regulate messenger RNA (mRNA) translation.1 MiRNA are involved in many cellular functions, such as contributing to cell plasticity required for the adaptation to changing environmental factors.2 The mode of action of miRNA have been extensively discussed in the literature.3 A miRNA can interact with multiple mRNAs and a mRNA can be targeted by multiple miRNAs.4 MiRNA are believed to aid in regulation of more than 30% of all protein-coding genes.5,6 Thus, there has been high interest to regulate these unconventional targets using exogenous chemical agents. The canonical actions of miRNA are to destabilise target mRNA via the dicer complex.7 AU-rich elements (AREs) can exist in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of mRNAs which can facilitate their degradation in a miRNA-dependent fashion.8,9

There are many miRNA involved in neuroinflammation and subsequent inhibition,10,11 each with the potential to interact with many different mRNAs.12 These factors underlay the complexity of miRNA modulation and the requirement to observe the effects of miRNA beyond the mRNA level. Despite the pivotal role of miRNA, few successful exogenous chemical probes target miRNA to regulate neuroinflammation. This work demonstrates two PNA miRNA inhibitors which can modulate miRNA activity and elicit an interesting and unexpected phenotype.

Microglia are residual macrophage cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are responsible for neuroinflammation.13 These cells are little understood; however, they are very important within the CNS and are of wide general interest.14 The microglia can respond to the presence of invading pathogens and illicit an inflammatory cascade.15 Typically, the inflammatory response in common macrophage cells is partially modulated by miRNA.11,16 In particular, two miRNA, miR-221-3p and miR-466l-3p have been shown to be important in the TLR4-mediated immune-response to lipopolysaccaride (LPS).17,18 Nonetheless, these effects have not been demonstrated in microglia nor has their effects upon down-stream signalling been established. We herein report that miR-221-3p and miR-466l-3p may provide novel, valid targets for regulating neuroinflammation. Furthermore, this work has demonstrated a transfection method applicable to a challenging microglial cell line with a transfection efficiency of approximately 75-80% (Fig. S1).

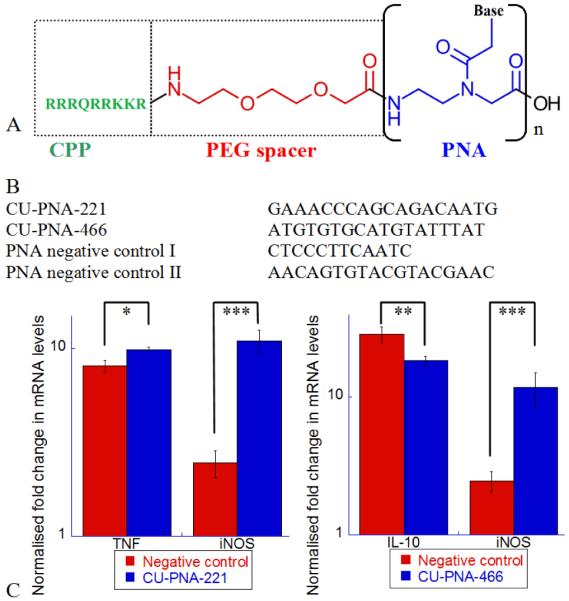

We have employed a chemical biology approach using synthetic miRNA inhibitors based on peptide nucleic acids (PNA), to effectively modulate LPS-induced inflammation in microglia cells. PNAs are synthetic DNA analogues which can specifically regulate miRNA targets.19 The structure of PNAs contains a poly-glycine scaffold with a nucleobase acetic acid coupled at every second backbone nitrogen (Fig. 1A). The PNA probes and controls used in this work are synthesized using an established solid state synthesis protocol.20 The PNA segment is generated using benzothiazole-2-sulfonyl (Bts) as an amine-protecting group as well as an acid-activating group. The subsequent deprotection by 4-methoxybenzenethiol and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) in dimethylformamide (DMF) affords high purity PNA oligomers (Fig. S2). The PNA motif is then conjugated with a cell penetrating peptide through a flexible (polyethylene glycol) PEG linker to facilitate cellular transfection (see Supplementary Methods for synthesis, purification, and characterisation).

Fig. 1.

PNA inhibitors and their effects on BV-2 microglia cells as analysed by quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). (A) The structure of a PNA miRNA inhibitor. The cell penetrating peptide (CPP, in green) used to facilitate passage across the cell plasma membranes. The PEG spacer (in red) separates the CPP from the PNA subunit (in blue). The PNA subunit presents complementary sequences for the miRNA of interest. (B) The sequences of the four PNA miRNA inhibitors used in this work. These represent the PNA sequence of the repeated subunit represented in Fig. 1A. (C) Left: The effects of CUPNA-221 upon TNF and iNOS mRNA 2 and 6 hours respectively, after a 400 ng ml−1 LPS challenge. Right: The effects of CU-PNA-466 upon IL-10 and iNOS mRNA 2 and 6 hours after an LPS challenge. Both these graphs are presented on a log scale with P-values represented as follows *<0.025, **<0.010 and, ***<0.005.

PNA molecules are resistant to protease and nuclease degradation as their backbones are substantially different from either protein or nucleic acids.21 Nonetheless, the similar hydrogen bonding pattern of the conjugated bases allows PNA to interact with natural oligonucleotides.22 This form of nucleic acid analogues are of increasing interest to researchers for a variety of biological probes.22 The versatility and stability of these molecules have made them of increasing interest in chemical biology. We have designed PNA miRNA inhibitors with complementary nucleotide sequences to miR-221-3p (CU-PNA-221) and miR-466l-3p (CU-PNA-466). Further, two negative control sequences (Fig. 1B) were used: 1) PNA negative control I: a short irrelevant sequence with minimal non-specific activities and 2) PNA negative control II: an 18 base irrelevant sequence validating that there is no effect of the reduced PNA length. All of these sequences were purified by HPLC and validated by MALDI-MS (Fig. S3).

Treatment with PNA inhibitors results in no significant change in miRNA level.23 The target miRNA is sequestered and miRNA activity is modulated without observable degradation.23 Thus, it is important to monitor changes in known targets of these miRNA to determine modulation of miRNA activity i.e. TNF for CU-PNA-221 and IL-10 for CU-PNA-466. Stimulation of BV-2 cells with LPS results in a rapid (within 2 hours) increase in TNF and IL-10 expression (Fig. 1C). Treatment with CU-PNA-221 leads to an increase of the TNF mRNA in cells (P 0.016) which is in accordance with our expectations.17 CU-PNA-466 induced a decrease of IL-10 (P 0.013) also in accordance with our expectations.18 Taken together, these results demonstrate that these miRNA inhibitors yield the expected effects.

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is responsible for the production of the inflammatory signalling molecule nitric oxide (NO).24 The transcription of iNOS mRNA increases upon stimulation with LPS reaching a maximum at 6 hours post stimulation (Fig. 1C).25 It is important to note that there is no significant change in neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) mRNA upon induction with LPS (Fig. S4). When the levels of iNOS mRNA are monitored by qPCR, the inhibition of either miR-221-3p or miR-466l-3p results in a substantial increase of iNOS mRNA compared with negative control I (P 0.0008 and 0.0009 for miR221-3p and miR466l-3p, respectively) (Fig. 1C). As iNOS is responsible for the production of the inflammatory signalling molecule NO,24 these data infer that these miRNA are anti-inflammatory. Elevation of the iNOS mRNA levels translated to an increase in iNOS protein level (Fig. S5) further supporting the theory that these two miRNAs elicit anti-inflammatory effects.

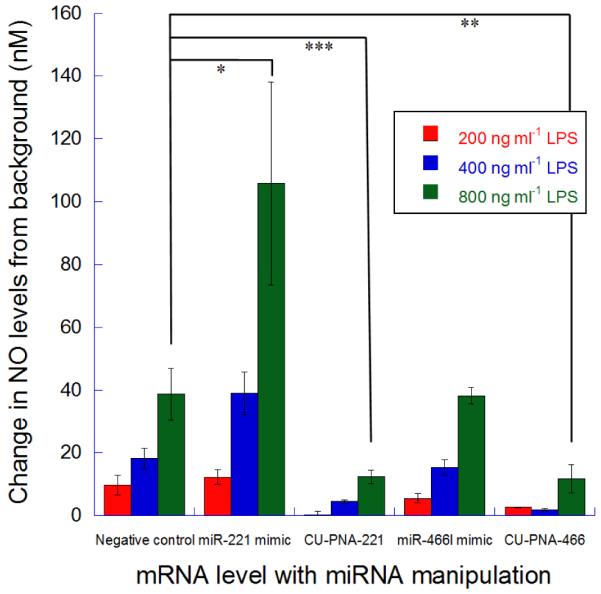

The production of NO by BV-2 cells can be monitored by a previously established reporter assay.26 The production of NO by BV-2 cells when treated with PNA inhibitors has been monitored alongside commercially available miRNA mimics (Fig. 2). The miRIDIAN miRNA mimics are double stranded RNA chemically modified to increase stability and selectively program the RISC complex with the miRNA of interest. Increasing concentrations of LPS result in increased expression of NO, as expected (Fig. 2). Both, CU-PNA-221 and CU-PNA-466 result in a statistically significant decrease in NO production when compared to PNA negative control I (P 0.0028 and 0.0069 respectively) (Fig. 2). CU-PNA-466 was tested against PNA negative control II to demonstrate these effects were not due to the difference in PNA length, this again presented a statistically significant decrease (P 0.0013) (Fig. S6). CU-PNA-466 also demonstrated a concentration dependence, and these effects only became apparent at transfection conditions over 100 nM (Fig. S7).

Fig. 2.

Changes in release of NO from BV-2 microglia cells upon miRNA modulation. The change in NO release levels from BV-2 cells under LPS stimulation (200, 400 and 800 ng ml−1) with miR-221-3p or miR-466l-3p modulations. These signals are normalised to the signal from cells treated with no LPS and are all taken after a 24 hour incubation. P-values represented as follows *<0.025, **<0.010 and, ***<0.005.

BV-2 cells treated with miR-221-3p mimics results in increased expression of NO (P 0.025); complementary to cells treated with CU-PNA-221 (Fig. 2). NO yield of cells treated with miR-466l-3p mimics gave no significant change compared to the negative control (P 0.92) which could be due to either or both of the following two reasons: (i) miR-466l-3p is at a high endogenous level and (ii) miR-466l-3p is occupying all available sites to elicit a pro-inflammatory effect so elevated levels can give no increased activity. These data contradict those outlined above and suggest that these two miRNA result in a pro-inflammatory effect.

These miRNA inhibitors increased both mRNA and protein level of iNOS but with no change in nNOS; however, the level of NO signalling was significantly retarded. With these factors in mind, it is logical to assume this phenotypic control is elicited post-translationally. The activity of iNOS is dependent on multiple cellular factors, one of which is calmodulin.27 Should these miRNA result in an up-regulation of calmodulin this could resolve this apparent contradiction. Canonically, miRNA degrade their target mRNAs; however, miR-466l-3p has been shown to increase the stability of AREs.18 Should miR-466l-3p increase the stability of calmodulin, a PNA inhibitor for this miRNA could decrease the levels of calmodulin thereby reducing iNOS activity.

A computational search using miRDB28,29 demonstrated that miR-466l-3p may potentially target the 3′-UTR of calmodulin mRNA. Using a miRDB search for murine calmodulin (NCBI GeneID:12313) 19 miRNA were predicted to target this mRNA. The top hit for this search was miR-466l-3p, with a confidence score of 85; (scores above 80 are assumed to be most likely of physiological relevance).28,29 The miRDB search returned two potential interaction sites (Fig. S8A) which cover the sequences of the AREs similar to those observed in IL-10.18 The levels of calmodulin mRNA were analysed by qPCR 12 hours post LPS stimulation (Fig. S8B). Calmodulin mRNA shows no significant change in cells treated with miR-466l-3p mimics; however, cells treated with PNA inhibitors show a significant (P 0.005) decrease in the level of calmodulin mRNA (Fig. S8B). The decreased calmodulin mRNA level corresponded to a decreased protein level, demonstrated by comparative immunoblotting (Fig. S9).

By using miRNA modulation we have elucidated the activities of two miRNA in the LPS response of BV-2 cells. These effects have been monitored on mRNA, protein and cell signalling levels. Contrary to expectations, inhibitors to two miRNA (miR-221-3p and miR-466l-3p) greatly reduce BV-2 cells ability to respond to an LPS challenge. Further, these miRNA modulate BV-2 cells response to LPS post-translationally. Direct experimental evidence has shown that miR-466l-3p targets and stabilises calmodulin mRNA via the miRNA activity upon the calmodulin mRNA 3′-UTR. The increased calmodulin mRNA stability and associated protein concentration can thus modulate iNOS protein activity. However, this would ideally be confirmed by further investigation by other methodologies e.g. 3′-UTR luciferase assay. A similar search was performed for miR-221-3p targets however; the exact mode of activity of CU-PNA-221 remains unknown and is a possible avenue for future research. These data exemplify the complexity of miRNA activities within cells due to their potential ancillary actions. Thus, this work has innovatively demonstrated that there is great importance in monitoring miRNA activity beyond the direct effects on target mRNA, in contrast to the present literature. The PNA molecules used in these studies may provide useful seeds for future drug design targeting these specific miRNAs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants GM101279, DA027977, DA026950, NS067425 and, DA025740. Hong Wang is acknowledged for initial screens of BV-2 cells.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

This article is part of the ChemComm ‘Emerging Investigators 2013’ themed issue

References

- 1.He L, Hannon GJ. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiu C, Chen G, Cui Q. Sci Rep. 2012;2 doi: 10.1038/srep00318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillai RS. RNA. 2005;11:1753–1761. doi: 10.1261/rna.2248605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson DW, Bracken CP, Goodall GJ. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis B, Burge C, Bartel D. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:351–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jing Q, Huang S, Guth S, Zarubin T, Motoyama A, Chen J, Di Padova F, Lin SC, Gram H, Han J. Cell. 2005;120:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenger-Gron M, Fillman C, Norrild B, Lykke-Andersen J. Mol Cell. 2005;20:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Neill LA, Sheedy FJ, McCoy CE. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nri2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nahid MA, Satoh M, Chan EKL. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:388–403. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Parker R. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:515–524. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leavy O. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:787–787. doi: 10.1038/nrn2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graeber MB. Science. 2010;330:783–788. doi: 10.1126/science.1190929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin L, Wu X, Block ML, Liu Y, Breese GR, Hong JS, Knapp DJ, Crews FT. Glia. 2007;55:453–462. doi: 10.1002/glia.20467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neill LAJ, Bowie AG. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Gazzar M, McCall CE. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20940–20951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma F, Liu X, Li D, Wang P, Li N, Lu L, Cao X. J Immunol. 2010;184:6053, 6059. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh S, Ju Y-S, Park H. Molecules and Cells. 2009;28:341–345. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee H, Jeon JH, Lim JC, Choi H, Yoon Y, Kim SK. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3291–3293. doi: 10.1021/ol071215h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker AL, Johnston APR, Caruso F. Macromol. Biosci. 2010;10:488–495. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200900347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shakeel S, Karim S, Ali A. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2006;81:892–899. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurreck Jens. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2003;270:1628–1644. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogdan C. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:907–916. doi: 10.1038/ni1001-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svensson C, Fernaeus SZ, Part K, Reis K, Land T. Brain Res. 2010;1322:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misko TP, Schilling RJ, Salvemini D, Moore WM, Currie MG. Anal Biochem. 1993;214:11–16. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akyol O, Zoroglu S, Armutcu F, Sahin S, Gurel A. In Vivo. 2004;18:377–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, El Naqa IM. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:325–332. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X. RNA. 2008;14:1012–1017. doi: 10.1261/rna.965408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.