Abstract

Chlorophenoxy compounds, particularly 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 4-chloro-2-methylphenoxy)acetic acid (MCPA), are amongst the most widely used herbicides in the United States for both agricultural and residential applications. Epidemiologic studies suggest that exposure to 2,4-D and MCPA may be associated with increased risk non-Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin's disease (HD), leukemia, and soft-tissue sarcoma (STS). Toxicological studies in rodents show no evidence of carcinogenicity, and regulatory agencies worldwide consider chlorophenoxies as not likely to be carcinogenic or unclassifiable as to carcinogenicity. This systematic review assembles the available data to evaluate epidemiologic, toxicological, pharmacokinetic, exposure, and biomonitoring studies with respect to key cellular events noted in disease etiology and how those relate to hypothesized modes of action for these constituents to determine the plausibility of an association between exposure to environmentally relevant concentrations of 2,4-D and MCPA and lymphohematopoietic cancers. The combined evidence does not support a genotoxic mode of action. Although plausible hypotheses for other carcinogenic modes of action exist, a comparison of biomonitoring data to oral equivalent doses calculated from bioassay data shows that environmental exposures are not sufficient to support a causal relationship. Genetic polymorphisms exist that are known to increase the risk of developing NHL. The potential interaction between these polymorphisms and exposures to chlorophenoxy compounds, particularly in occupational settings, is largely unknown.

1. Introduction

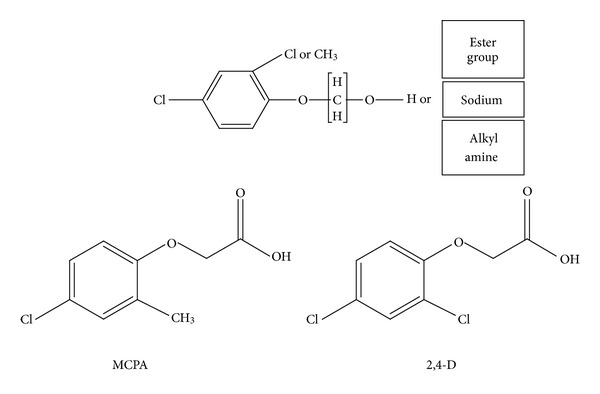

The chlorophenoxy herbicides MCPA and 2,4-D are registered for a range of agricultural and residential uses focused on control of postemergent broadleaf weeds. Since 2001, 2,4-D has been the most commonly used herbicide in the residential market at 8 to 11 million pounds annually and is the seventh most commonly used herbicide in the agricultural market ranging from 24 to 30 million pounds annually (http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/pestsales/07pestsales/usage2007_2.htm#3_5/). MCPA is used less, falling within the top 25 compounds used residentially and agriculturally, but is a closely related compound. Phenoxy herbicides act by simulating the action of natural hormones to produce uncoordinated plant growth. Their action is selective as they are toxic to dicotyledonous but not monocotyledonous plants. The physical properties of chlorophenoxy compounds can vary greatly according to formulation. For instance, as alkali salts they are highly water soluble (can be formulated as aqueous solutions), whereas as simple esters they demonstrate low water solubility and are more lipophilic (generally formulated as emulsifiable concentrates). The acid is the parent compound, but a number of formulations in use contain the more water-soluble amine salts or the ester derivatives, which are readily dissolved in an organic solvent. Figure 1 shows the general chemical structure of the chlorophenoxy herbicides, together with the structures of the parent compounds MCPA and 2,4-D.

Figure 1.

General chemical structure of chlorophenoxy compounds and 2,4-D and MCPA.

A series of rodent bioassays submitted to the US EPA in support of pesticide registration have found no carcinogenic treatment-related effects for either MCPA [1–5] or 2,4-D [6–8]. Regulatory agencies in their evaluations of these two constituents have found them unlikely to be human carcinogens [3, 4] or unclassifiable as to carcinogenicity [8–10] while the World Health Organization (WHO) has concluded that 2,4-D and its salts and esters are not genotoxic, specifically, and the toxicity of the salts and esters of 2,4-D is comparable to that of the acid [11]. However, a number of epidemiologic studies have found positive associations between some measure of exposure either to chlorophenoxy compounds and/or MCPA and/or 2,4-D in particular and an increased risk of some lymphohematopoietic cancers, primarily non-Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL) [12–14], but also Hodgkin's disease (HD), soft-tissue sarcoma (STS), and to a lesser extent, leukemia, while others have found no associations [15, 16] or only in combination with other compounds or with multiple chlorophenoxys [17].

Under the assumption that the epidemiologic studies reveal a potential association between exposure and outcome, there must be a series of cellular events by which exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds is causally related to these carcinogenic outcomes. The toxicological studies are equivocal. While the traditional in vivo rodent assays are all negative for tumorigenic responses, and a number of in vivo and in vitro studies of potential mutagenicity and clastogenicity are negative [18–20], a number of other in vitro studies have shown weakly positive responses for chromosomal aberrations, sister chromatid exchange [SCE], and increased micronucleus formation and replicative index [21], but typically only at the highest concentrations and/or doses tested exceeding renal transport mechanisms or observed effects were transient. In addition, several studies have demonstrated the ability of 2,4-D to interrupt cellular functions and communication [22, 23], suggesting a potential nongenotoxic mode of action. Chlorophenoxy compounds are known to induce P450 [24] and to effectively bind to plasma proteins. Both 2,4-D and MCPA have been shown in studies ranging from rats to dogs to humans to be largely excreted as parent compounds and to a lesser extent as conjugates via urine within hours of exposure [25, 26]. There is general agreement that chlorophenoxy compounds do not accumulate in tissues.

There have been numerous previous reviews evaluating the evidence for potential health effects associated with exposures to 2,4-D in particular as summarized in Table 1. The US EPA, US EPA Science Advisory Board, IARC, WHO, and Canadian government independently have conducted assessments of the carcinogenicity of 2,4-D, MCPA, and/or chlorophenoxy compounds generally [5, 9, 34, 45–48]. In 1991, the Center for Risk Analysis at the Harvard School of Public Health convened a panel of 13 scientists to weigh the evidence on the human carcinogenicity of 2,4-D [37]. The panel based its findings on a review of the toxicological and epidemiologic literature up to that time on 2,4-D and related phenoxy herbicides. The panel concluded that the toxicological data alone do not provide a strong basis for determination of carcinogenicity of 2,4-D. However, although they were unable to establish a cause-effect relationship, the panel concluded there was suggestive although inconclusive evidence for an association between exposure to 2,4-D and NHL and that further study was warranted. The panel further concluded there was little evidence of an association between 2,4-D use and soft-tissue sarcoma or Hodgkins disease and no evidence of an association between 2,4-D use and any other form of cancer.

Table 1.

Summary of reviews of 2,4-D and/or MCPA.

| Reference | Evaluation | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory reviews or reviews in support of regulatory activities | ||

|

| ||

| US EPA, SAB [27] | Science Advisory Board consultation on carcinogenicity of 2,4-D | “Data are not sufficient to conclude that there is a cause and effect relationship between exposure to 2,4-D and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.” |

|

| ||

| US EPA [28] | 4th carcinogenicity of 2,4-D peer review | Not classifiable as to carcinogenicity. |

|

| ||

| WHO/IARC [29] | Evaluations of carcinogenic risk | Inadequate and/or limited for 2,4-D specifically and chlorophenoxy compounds generally. |

|

| ||

| US EPA [5] | Health Effects Division Carcinogenicity Peer Review Committee (2,4-D) | “Evidence is inadequate and cannot be interpreted as showing either the presence or absence of a carcinogenic effect.” |

|

| ||

| European Commission [30] | Review report for 2,4-D | Proposed uses have no harmful effects on animal or human health; no evidence of carcinogenicity. |

|

| ||

| US EPA [3, 4] | Risk assessments and reregistration decision for MCPA | Limited evidence for carcinogenicity. |

|

| ||

| US EPA [8] | Risk assessments and reregistration decision for 2,4-D | Group D, not classifiable as to carcinogenicity. |

|

| ||

| Health Canada PMRA [31] | Reregistration decision for 2,4-D | No evidence of carcinogenicity. |

|

| ||

| Health Canada PMRA [32] | Reregistration decision for MCPA | No evidence of carcinogenicity. |

|

| ||

| Health Canada [9] | MCPA in drinking water | Not considered a carcinogen. |

|

| ||

| 77FR23135 [33] | Response to NRDC petition to revoke 2,4-D registration | No new evidence that would suggest registration should be revoked. |

|

| ||

| Nonregulatory reviews | ||

|

| ||

| Canadian Centre for Toxicology [34] | Expert panel on carcinogenicity of 2,4-D | No evidence that 2,4-D forms reactive intermediates in the liver or other tissues or forms adducts with DNA. Existing animal and human data are insufficient to support the finding that 2,4-D is a carcinogen; insufficient evidence that existing uses of 2,4-D pose a significant human health risk. |

|

| ||

| Kelly and Guidotti [35] | Review of literature to advise provincial regulatory body on chlorophenoxy safety, particulary 2,4-D | Evidence for a causal association is strongest for NHL and probably reflects either a weak effect or, possibly, a confounding exposure associated with the use of 2,4-D. Given worst-case assumptions, potency of 2,4-D as a carcinogen is probably weak. Its intrinsic toxicity is less than that of alternative herbicides. |

|

| ||

| Johnson [36, 36] | 13 cohort studies (9 cohorts) in chlorophenoxy manufacturing; 16 cohort studies (12 cohorts) in chlorophenoxy spraying | The weight of evidence does not unequivocally support an association between use of chlorophenoxys and malignant lymphomas/STS; occupational cohort studies have not accumulated sufficient person-years of observation to date, yet see cases of myeloid lymphoma and STS when none are expected. |

|

| ||

| Ibrahim et al. [37] | Human carcinogenicity of 2,4-D | The toxicological data alone do not provide a strong basis for determination of carcinogenicity of 2,4-D. Suggestive although inconclusive evidence for an association between exposure to 2,4-D and NHL based on epi studies and further study was warranted. Little evidence of an association between 2,4-D and STS or HD, and no evidence of an association between 2,4-D use and any other form of cancer. |

|

| ||

| Munroe et al. [38] | Comprehensive, integrated review of 2,4-D safety in humans | No evidence for adverse health effects; no mechanistic basis by which 2,4-D could cause cancer. |

|

| ||

| Morrison et al. [14] | Meta analysis of epidemiological studies involving occupational exposures to chlorophenoxy compounds | Suggestive evidence of an association with NHL; no evidence for an association with STS, HD, or leukemia. |

|

| ||

| Bond and Rossbacher [39] | Potential carcinogenicity of MCPA, MCPP, 2,4-DP | No evidence for carcinogenicity across all three compounds. |

|

| ||

| Henschler and Greim [40] | Comprehensive, integrated review to establish “maximale arbeitsplatz konzentration” | Evidence for potential proliferative response; less evidence for genotoxicity. |

|

| ||

| Gandhi et al. [41] | Potential carcinogenicity of 2,4-D | Some suggestive evidence for an association with NHL but without any plausible mode of action. |

|

| ||

| Garabrant and Philbert [42] | Comprehensive, integrated review of potential for health effects in humans | No causal association of any form of cancer with 2,4-D exposure. Animal studies of acute, subchronic, and chronic exposure to 2,4-D, its salts, and esters showed an unequivocal lack of systemic toxicity at doses that did not exceed renal clearance mechanisms. No evidence that 2,4-D in any of its forms activated or transformed the immune system in animals at any dose. |

|

| ||

| Bus and Hammond [43] | Update on data generated by the Industry Task Force II on 2,4-D Research Data | Toxicity responses limited to highest doses; not a carcinogen or genotoxicant, does not cause birth defects; low potential for reproductive toxicity and neurotoxicity. |

|

| ||

| Van Maele-Fabry et al. [44] | Cohort studies for chlorophenoxy expousures and leukemia | Meta-analysis of 3 cohort studies; statistically significant odds ratio = 1.60, 95% confidence interval = 1.02–2.52; all three underlying studies individually showed non-significant associations. |

Focusing specifically on the epidemiologic studies, Johnson [36] conducted a review of the association between exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds and NHL, STS, HD, and other malignant lymphomas based solely on occupational cohort studies, and determined the weight of evidence at that time did not unequivocally support an association between use of chlorophenoxys and malignant lymphomas and/or STS, and that the available occupational cohort studies had not yet accumulated sufficient person years of observation to date. Nonetheless, despite the lack of sufficient person-years of observation, cases of lymphoma, and STS were observed when none were expected, suggestive of a potential association.

Munroe et al. [38] published a “comprehensive, integrated review and evaluation of the scientific evidence relating to the safety of the herbicide 2,4-D” and found no evidence for adverse effects across a range of outcomes. Focusing specifically on cancer, the authors found that only the case-control studies provided any evidence of an association between exposure to 2,4-D and NHL, specifically, and that this association was not borne out by the cohort studies. Finally, in an evaluation of the in vitro and in vivo data, they found no support for a mechanistic basis by which 2,4-D might lead to NHL.

Also in 1992, Morrison et al. [14] conducted a review of the literature and determined there was reasonable evidence suggesting that occupational exposure to phenoxy herbicides resulted in increased risk of developing NHL. The authors noted several studies showing large increases in risk of STS with phenoxy herbicide exposure but acknowledged that other studies had failed to observe increased risks and evidence for an exposure-risk relationship was lacking. A number of the underlying studies, particularly those showing elevated risks, included exposures to other constituents, such as dioxins.

In 1993, Bond and Rossbacher [39] published a review of potential human carcinogenicity of the chlorophenoxy herbicides MCPA, 2-(2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxy)propanoic acid (MCPP), and 2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)propionic acid (2,4-DP). They evaluated the epidemiologic evidence, particularly based on European studies, for associations between exposure to chlorophenoxy herbicides and cancer, including NHL, HD, and STS. The authors concluded that although suggestive evidence from epidemiologic studies of associations between chlorophenoxy herbicides and increased risks for several uncommon cancers existed, the evidence was inconsistent and far from conclusive. Further, none of the evidence specifically implicated MCPA, MCPP, or 2,4-D. Furthermore, the results of experimental studies in laboratory animals did not support a causal association between exposure these three compounds and cancer development. Similarly, Gandhi et al. [41] developed a critical evaluation of cancer risk from 2,4-D and found that there was no evidence for carcinogenicity of 2,4-D, although there was some suggestive evidence for NHL as an outcome, but without a plausible mode of action.

In 2002, Garabrant and Philbert [42] reviewed the scientific evidence from studies in both humans and animals relevant to cancer risks, neurologic disease, reproductive risks, and immunotoxicity of 2,4-D and its salts and esters focusing particularly on studies conducted from 1995 through 2001. The authors concluded that the available evidence from epidemiologic studies did not indicate any causal association of any form of cancer with 2,4-D exposure. Further, they found no human evidence of adverse reproductive outcomes related to 2,4-D. The available data from animal studies of acute, subchronic, and chronic exposure to 2,4-D and its salts and esters showed an unequivocal lack of systemic toxicity at doses that did not exceed renal clearance mechanisms. They found no evidence that 2,4-D in any of its forms activated or altered the immune system in animals at any dose. At doses exceeding or approaching renal clearance mechanisms, approximately 50 mg/kg in rats [49] 2,4-D was observed to cause liver and kidney damage and irritated mucous membranes. Although myotonia and alterations in gait and behavioral indices were observed following doses of 2,4-D that again exceeded renal clearance mechanisms, alterations in the neurologic system of experimental animals were not observed with the administration of doses in the microgram/kg/day range. The authors found it unlikely that 2,4-D exhibited any potential health effects at doses below those required to induce systemic toxicity.

Bus and Hammond [43] summarized the findings of animal and human health studies primarily conducted or sponsored by the Industry Task Force II on 2,4-D Research Data (2,4-D Task Force) using the three forms of 2,4-D (acid, dimethylamine salts, and 2-ethylhexyl ester) and reported that chronic and other toxicity responses were generally limited to high doses, well above those known to result in nonlinear pharmacokinetic behavior. They further reported that 2,4-D did not demonstrate carcinogenicity or genotoxicity in animals, did not cause birth defects, and demonstrated low potential for reproductive toxicity and neurotoxicity, based on the additional studies provided to the US EPA in support of 2,4-D reregistration.

Despite these numerous reviews and several regulatory evaluations, questions as to the carcinogenic potential of 2,4-D and related compounds persist, prompting this paper.

1.1. Integrated Evaluation

There are a number of proposed approaches for evaluating the weight of evidence for a causal association between a particular exposure and a set of outcomes all of which rely to some extent on the use of Hill's criteria as applied to the body of evidence [50]. But defining criteria weights and the specific details of how the criteria are applied requires a clear definition of what constitutes “weight” and what constitutes “evidence” and how those components relate to each other without appearing ad hoc or purely the result of professional judgment. Ideally, one could use decision analytic techniques in which each individual study would receive a quantitative score across each of the clearly defined criteria resulting in an “objective” evaluation, but this becomes somewhat intractable, particularly in this case, given the large number of studies, the categories of studies (e.g., epidemiologic, in vivo and in vitro, and exposure), and the nuanced details of each study.

Hypothesis-based weight-of-evidence [51, 52] provides a useful framework for evaluating hypotheses related to potential modes of action of chemical toxicity. Mode of action has regulatory significance with respect to the model used to develop toxicity factors and dose-response relationships for use in risk assessments [53], particularly with respect to carcinogenic outcomes, but most frameworks start with the premise that there is tumor induction observed in animal studies [54], which is not the case for 2,4-D or MCPA. Therefore, under the assumption that the epidemiologic studies are suggestive of an association between exposure to 2,4-D and/or MCPA and certain lymphohematopoietic outcomes, there is a benefit to evaluate those lymphohematopoietic outcomes with respect to disease etiology to identify key cellular events involved in either disease initiation or promotion to determine how those might relate to a potential mode of action for chlorophenoxy compounds to exert their biological influence. This strawman approach provides a framework for evaluating how much of the burden of disease might be attributable to environmental factors, specifically exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds. Since 2001, the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium has dedicated itself to provide an open scientific forum and collaborative platform across which to pool data and conduct analyses related to lymphomas, particularly NHL. These investigators have made significant progress in identifying molecular pathways and events leading to subclinical progression of disease [55] that are explored here in the context of chlorophenoxy exposures. Is there evidence for a relationship between exposure and development of molecular events required for disease progression? And if so, how would exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds in the environment contribute to those events? And finally, are exposure concentrations sufficient to plausibly contribute to disease incidence? What is the evidence for population-level exposures, and how do those relate to concentrations at which effects have been observed across the different categories of studies (e.g., in vivo and in vitro toxicological, epidemiologic)?

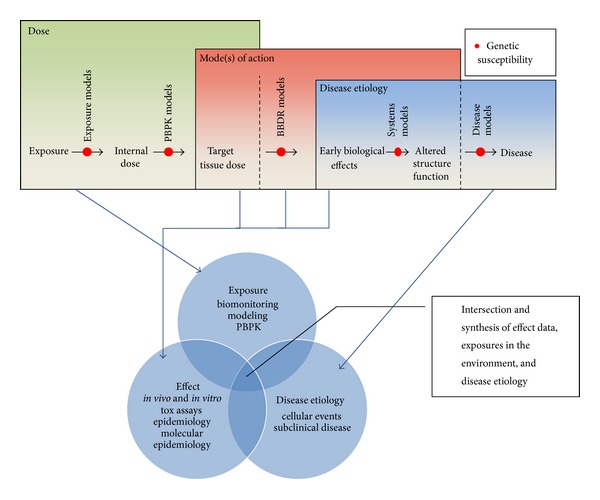

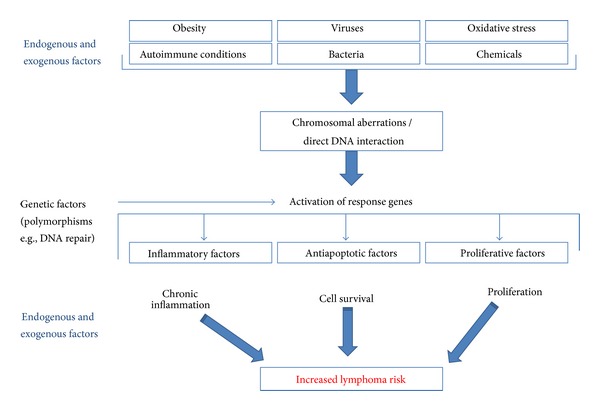

Figure 2 shows that synthesizing this information to determine the potential for exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds at environmentally relevant concentrations to lead to specific carcinogenic outcomes requires a critical evaluation of the intersection of environmental exposures (what are the exposure concentrations in the environment and how do those relate to biologically effective doses), the evidence for particular effects from toxicological and epidemiological data, and what is known about cellular events at the subclinical scale in terms of disease etiology. This allows an evaluation of biological plausibility with respect to a hypothesized mode of action based on the best available understanding of molecular events required for disease progression, evaluated in the context of what is known about how these compounds exert their biological influence, and exposure conditions necessary to achieve absorbed doses relevant to the pathways of interest.

Figure 2.

Intersection of data required to evaluate the plausibility of an association between exposure and outcome.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, the rationale for focusing on lymphohematopoietic cancers is provided in Section 2 by summarizing and evaluating the key epidemiologic studies that have demonstrated an association between some measure of exposure to 2,4-D, MCPA, and/or chlorophenoxy compounds generally and lymphohematopoietic cancers. Section 3 takes a “top down” approach by evaluating what is known about disease etiology to develop hypotheses concerning potential modes of action by which exposure to 2,4-D and/or MCPA might lead to the particular health outcomes identified in Section 2. Section 4 identifies, discusses, and interprets the literature and data with respect to the kinetics of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination in laboratory studies in humans and animals (Section 4.1), followed by a subsection on pharmacodynamics. Section 5 focuses on toxicological studies, both in vivo and in vitro, starting with animal studies (Section 5.1) and then available human studies (Section 5.2). Section 6 discusses exposures in the environment based on the available biomonitoring data and modeling studies in the context of the hypothesized modes of action. This is followed by a synthesis of the evidence in Section 7.

2. Epidemiologic Studies

This section identifies the available epidemiologic studies and evaluates them with respect to a number of questions to identify the specific carcinogenic outcomes of interest. The first set of questions relates generally to study design, including the following.

How was exposure quantified? A key limitation of epidemiological studies is related to the way in which exposures are quantified at best and categorized at worst. Many epidemiological studies rely on relatively crude measures of exposure such as basic occupational status (e.g., farmer, chlorophenoxy manufacturing) with years on the job as the primary measure of more or less exposure. Other studies make an attempt to quantify pounds of active constituent produced (for manufacturing facilities) or used (for sprayers, farmers, etc.). This information may or may not be combined with estimates of duration (e.g., two months a year for 12 years, etc.). Particularly for constituent usage, most estimates rely on questionnaires of various kinds, and in some cases, only next of kin is available to answer these questions. Studies that are able to use quantitative exposure information (e.g., biomarkers, etc.) allow for greater confidence in any observed associations.

What covariates were evaluated? It is important to evaluate potential covariates of interest that might be related to disease (e.g., smoking) and certainly across the entire study population. This could include other potential exposures (e.g., solvents, other chemicals), and even if these arenot included directly in the evaluation, it is important to understand potential differences in exposures across the study population (e.g., cases have higher solvent exposures than controls, etc.). If the study is attempting to evaluate exposure across a number of constituents, then the statistical treatment needs to reflect these multiple comparisons to avoid spurious associations.

Is latency considered? Most cancers require a series of events to occur over time following exposure; a study in which exposure and outcome are largely concurrent is less compelling than a study that has thought through the latency question. Weisenburger [100] suggests that the latency period for NHL, HD, leukemia for long term, and chronic exposures is on the order of 10–20 years as compared to short-term, high-intensity exposures for which the latency period is significantly shorter, on the order of five to six years.

How long was the follow-up period in cohort studies? Related to latency but not exactly the same is the follow-up period in cohort studies. Again, particularly for chronic exposures and/or outcomes that are not expected for some time following exposure, it is important to allow enough follow-up time.

How were cases and controls selected in case-control studies? Clearly, systematic differences across cases and controls will influence the analysis, particularly with respect to potential exposures.

How were outcomes identified and categorized? In general, epidemiological studies rely on ICD classifications in use at the time of the study, but these change over time as our understanding of clinically relevant differences in disease become apparent. There is also the question of grouping outcomes with respect to mode of action. For example, within lymphohematopoietic outcomes, which include both lymphomas and leukemias, there are different cellular and molecular origins to disease relevant to the potential mode of action of an exposure such that it may not be appropriate to consider outcomes too broadly. That said, there may not be enough power to detect measurable differences across histological subtypes (e.g., follicular versus mantle cell lymphoma).

Another set of questions concerns the analysis and results, including the following.

What is the power of the study? A challenge in epidemiological studies, particularly case-control studies with rare outcomes, is the power of the study to detect a relative risk of a certain magnitude.

Is there a dose-response relationship with measures of exposure (e.g., job duration, years of use, etc.)? In general, there is an expectation that higher and/or longer exposure would be associated with higher risk, depending on the potential mode of action of the compound.

What statistical tests are used? As mentioned above, in the event of multiple exposures and comparisons, the statistical model used needs to account for that to avoid spurious associations.

Candidate studies were identified through a literature search, using PubMed, Medline, and Web of Science, for all epidemiologic studies related to 2,4-D, MCPA, and/or chlorophenoxy compounds and lymphohematopoietic cancers. Search terms included “lymph*” and “2,4-D,” or “MCPA,” “chlorophenoxy,” or “phenoxyacetic” and “human.” References for citations obtained this way were carefully reviewed to identify additional relevant studies. Papers were categorized as to type of study (e.g., case control, cohort) and general cohort (e.g., Swedish forestry workers, Finnish chlorophenoxy producers, US agricultural study, etc.). Results from the most recent, nonoverlapping analyses were the focus of this assessment.

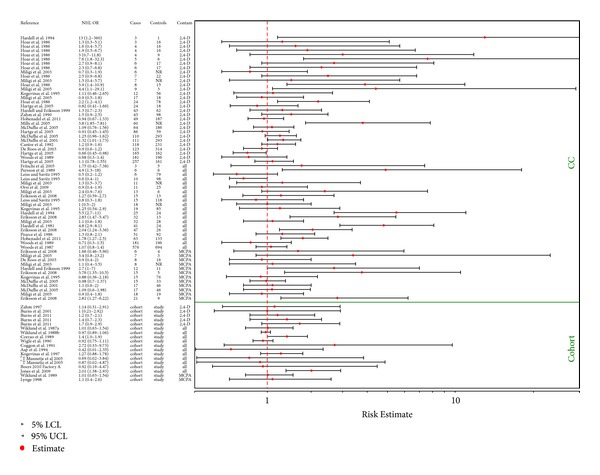

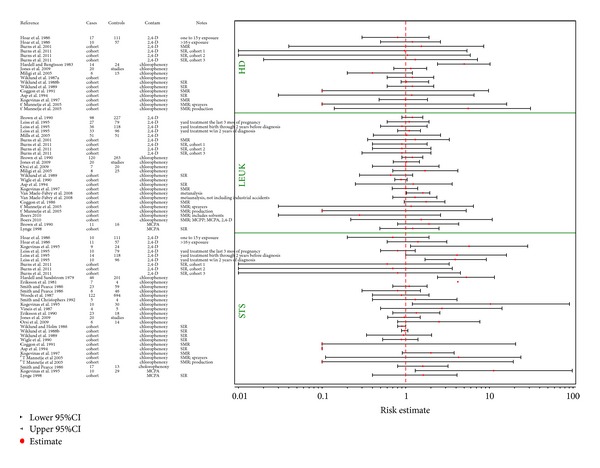

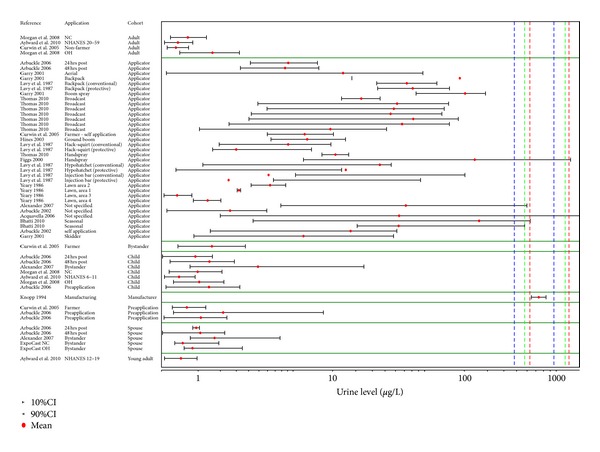

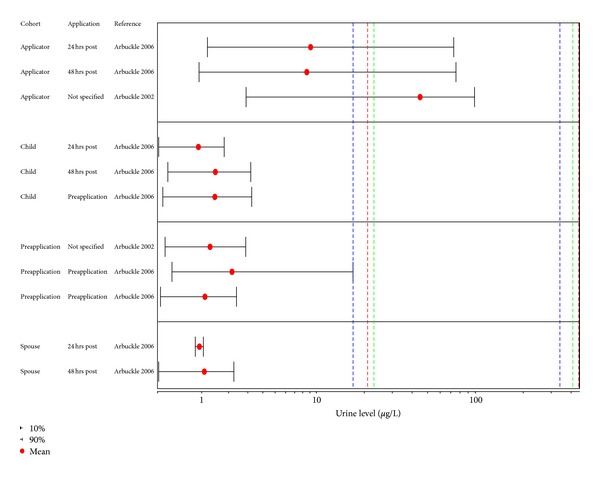

Several studies in occupationally exposed case-control and to a lesser extent cohort studies show statistically significant associations (Figures 3 and 4) with a number of lymphohematopoietic outcomes, and these are the basis for concern with respect to potential health effects associated with exposures to 2,4-D and/or MCPA. Figure 3 provides an overview of the epidemiologic studies related to NHL as an outcome, while results for the remaining cancers are graphically depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Summary of epidemiologic studies for NHL (see for review [12, 15–17, 56–89]).

Figure 4.

Summary of epidemiologic studies for STS, HD, and leukemia (see for review [12, 44, 57, 59, 66, 70, 75–80, 80–87, 89–99]).

2.1. Case-Control Studies

2.1.1. NHL

Table 2 provides a summary of available case-control studies that have evaluated NHL as an outcome. Figure 3 provides these results in a graphical format.

Table 2.

Case-control studies of chlorophenoxy compounds and NHL.

| NHL OR | Cases | Controls | Reference | Herbicide | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.8 (2.9–8.1) | 41 | 24 | Hardell et al. [72] | 2,4,5-T; 2,4-D; MCPA | Chlorophenols, solvents, and other pesticides. Exposure defined as greater than one day; entirely self-reported. One documented MCPA exposure across cases; results for NHL and HD combined. Forestry. |

|

| |||||

| 4.9 (1.3–18) | 6 | 6 | Persson et al. [68] | Phenoxys | Chlorophenols, solvents, and other pesticides. Variety of occupations and exposure described by occupation. Exposure to wood preservatives/creosote predicted much higher ORs; exposure to pets comparable. Only logistic model statistically significant. |

|

| |||||

| 13 (1.2–360) | 3 | 1 | Hardell et al. [56] | 2,4-D only | Chlorophenols. Potential for recall bias in questionnaires used for exposure. No dose response relationship observed. Forestry. |

|

| |||||

| 5.5 (2.7–11) | 25 | 24 | Hardell et al. [56] | Phenoxys (including 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T, and MCPA) | 2,4,5-T known to contain dioxin. No dose response relationship observed. |

|

| |||||

| 2.7 (1.0–7.0) | 12 | 11 | Hardell and Eriksson [60] | Primarily MCPA | Greater than 30 year latency to achieve statistical significance. |

| 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 43 | 62 | Hardell and Eriksson [60] | 2,4-D/2,4,5-T | |

|

| |||||

| 2.81 (1.27–6.22) | 21 | 9 | Eriksson et al. [71] | MCPA only overall | Questionnaire on work history; questions on exposure to pesticides, organic solvents, and other chemicals. Numbers of years, days per year, and approximate length of exposure per day. No job-exposure matrix could be developed. One full day of exposure constituted exposure. |

| 3.76 (1.35–10.5) | 15 | 5 | Eriksson et al. [71] | MCPA < 32 days of use | |

| 1.66 (0.46–5.96) | 6 | 4 | Eriksson et al. [71] | MCPA > 32 days of use | |

| 2.04 (1.24–3.36) | 47 | 26 | Eriksson et al. [71] | Phenoxys overall | |

| 2.83 (1.47–5.47) | 32 | 13 | Eriksson et al. [71] | Phenoxys < 45 days of use | |

| 1.27 (0.59–2.70) | 15 | 13 | Eriksson et al. [71] | Phenoxys > 45 days of use | |

|

| |||||

| 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 51 | 92 | Pearce et al. [73] | Primarily 2,4,5-T; MCPA not mentioned | Fencing work; employment in meat works statistically significant. “Farming” assumed to represent chlorophenoxy exposures. |

|

| |||||

| 2.2 (1.2–4.1) | 24 | 78 | Hoar et al. [57] | 2,4-D (overall, not stratified) | No dose response (see below). |

|

| |||||

| 2.7 (0.9–8.1) | 6 | 17 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D 1-2 d/y (frequency) | Only overall analysis statistically significant; no dose response relationship. Many other exposures; use of hierarchical modeling by class (herbicides only, insecticides only, etc.). Detailed questionnaire; but elicited dates and frequency of use of any herbicide on each farm instead of dates and frequency for each specific herbicide. |

| 1.6 (0.4–5.7) | 4 | 16 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D 3–5 d/y (frequency) | |

| 1.9 (0.5–6.7) | 4 | 16 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D 6–10 d/y (frequency) | |

|

| |||||

| 3.0 (0.7–11.8) | 4 | 9 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D 11–20 d/y (frequency) | |

| 7.6 (1.8–32.3) | 5 | 6 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D > 21 d/y | Only overall analysis statistically significant; no dose response relationship. Many other exposures; use of hierarchical modeling by class (herbicides only, insecticides only, etc.). Detailed questionnaire; but elicited dates and frequency of use of any herbicide on each farm instead of dates and frequency for each specific herbicide. |

| 1.3 (0.3–5.1) | 3 | 16 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D 1–5 yrs (duration) | |

| 2.5 (0.9–6.8) | 7 | 22 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D 6–15 yrs (duration) | |

| 3.9 (1.4–10.9) | 8 | 15 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D 16–25 yrs (duration) | |

| 2.3 (0.7–6.8) | 6 | 17 | Hoar et al. [57] | Use of 2,4-D > 26 yr (duration) | |

|

| |||||

| 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | 43 | 98 | Zahm et al. [61] | 2,4-D | Lawn care professionals. |

|

| |||||

| 1.07 (0.8–1.4) | NR | NR | Woods et al. [66] | Phenoxys; other compounds | Increased risks found for DDT (1.82 (1.04-3.2)) and organic solvents (1.35 (1.06-1.7)). Exposure based on job description. No dose response observed for phenoxys. |

|

| |||||

| 0.68 (0.3–1.4) | 181 | 196 | Woods [65] | 2,4-D | Small but significant excess risk observed for farmers (all chemicals). Exposure poorly defined. |

| 0.71 (0.3–1.5) | 181 | 196 | Woods [65] | Any phenoxy | |

|

| |||||

| 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 118 | 231 | Cantor et al. [64] | Largely 2,4-D | Statistically significant OR > 1.5 for personal handling, mixing, or application of carbaryl, chlordane, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, diazinon, dichlorvos, lindane, maialinoli, nicotine, and toxaphene. |

|

| |||||

| 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 6 | 79 | Leiss and Savitz [69] | Yard treated in last three months of pregnancy | Exposure dichotomous never exposed versus ever exposed; actual products and durations not specified. Lymphomas considered as a category. |

| 0.8 (0.3–1.8) | 15 | 118 | Leiss and Savitz [69] | Yard treated in the two years between birth and diagnosis | |

|

| |||||

| 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 10 | 98 | Leiss and Savitz [69] | Yard treated in the two years prior to diagnosis | Exposure dichotomous never exposed versus ever exposed; actual products and durations not specified. Lymphomas considered as a category. |

|

| |||||

| 1.25 (0.54–2.90) | 19 | 85 | Kogevinas et al. [59] | Phenoxys | Exposure evaluated for phenoxy herbicides and chlorophenols, polychlorinated dibenzodioxins and furans, raw materials, process chemicals, and chemicals used in the production of phenoxy herbicides. |

| 0.88 (0.36–2.18) | 15 | 76 | Kogevinas et al. [59] | MCPA/MCPP | Three industrial hygienists carried out questionnaire-based analysis of exposure to 21 chemicals or mixtures. Nested case-control in IARC cohort [83]. |

|

| |||||

| 1.11 (0.46–2.65) | 12 | 56 | Kogevinas et al. [59] | 2,4-D/P/B | See previous/above |

|

| |||||

| 1.32 (1.01–1.73) | 111 | 293 | McDuffie et al. [13] | 2,4-D | Small validation study of exposure questionnaire. Considered many covariates and exposures. Final models did not include MCPA or 2,4-D. Previous cancer and family history strong predictors. |

| 1.10 (0.6–2.0) | 17 | 46 | McDuffie et al. [13] | MCPA | |

|

| |||||

| 1.25 (0.96–1.62) | 110 | 293 | McDuffie et al. [62] | 2,4-D | Cross-Canada study. Mecoprop exposures show strongest relationship; also DEET. |

| 1.09 (0.6–1.98) | 17 | 46 | McDuffie et al. [62] | MCPA | |

|

| |||||

| 1.09 (0.76–1.56) | 64 | 186 | McDuffie et al. [62] | 2,4-D | Farm study. Mecoprop exposures show strongest relationship; also DEET. |

| 0.98 (0.7–1.37) | 15 | 33 | McDuffie et al. [62] | MCPA | |

|

| |||||

| 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 123 | 314 | De Roos et al. [16] | 2,4-D | Pooled data from three previous case-control studies. |

| 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 8 | 16 | De Roos et al. [16] | MCPA | Strongest associations for organophosphates, chlordane, and dieldrin. |

|

| |||||

| 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 18 | NR | Miligi et al. [58] | Chlorophenoxys and men | |

| 1.3 (0.5–3.7) | 11 | NR | Miligi et al. [58] | Chlorophenoxys and women | Crop exposure matrix for exposure based on face-to-face interview questionnaire together with pesticide usage statistics by area. |

| 0.7 (0.3–1.9) | 6 | NR | Miligi et al. [58] | 2,4-D and men | |

| 1.5 (0.4–5.7) | 7 | NR | Miligi et al. [58] | 2,4-D and women | |

| 1.1 (0.4–3.5) | 8 | NR | Miligi et al. [58] | MCPA and women | |

| 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 32 | 28 | Miligi et al. [58] | Chlorophenoxys overall | |

| 2.4 (0.9–7.6) | 13 | 6 | Miligi et al. [58] | Chlorophenoxys without protective equipment | |

| 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | 17 | 18 | Miligi et al. [87] | 2,4-D overall | |

|

| |||||

| 4.4 (1.1–29.1) | 9 | 3 | Miligi et al. [87] | 2,4-D without protective equipment | |

| 0.9 (0.4–1.8) | 18 | 19 | Miligi et al. [87] | MCPA overall | Crop exposure matrix for exposure based on face-to-face interview questionnaire together with pesticide usage statistics by area. |

| 3.4 (0.8–23.2) | 7 | 3 | Miligi et al. [87] | MCPA without protective equipment | |

|

| |||||

| 1.1 (0.78–1.55) | 257 | 161 | Hartge et al. [15] | 500 ng/g 2,4-D in carpet dust | |

| 0.91 (0.45–1.45) | 86 | 59 | Hartge et al. [15] | 500–999 ng/g 2,4-D in carpet dust | No dose response observed; residential exposures from tracking following yard application. Measured exposures but not concurrent. |

| 0.66 (0.45–0.98) | 165 | 162 | Hartge et al. [15] | 1000–9999 ng/g 2,4-D in carpet dust | |

|

| |||||

| 0.82 (0.41–1.66) | 24 | 18 | Hartge et al. [15] | >10000 ng/g 2,4-D in carpet dust | See previous/above. |

|

| |||||

| 3.8 (1.85–7.81) | 60 | NR | Mills et al. [12] | 2,4-D | US farmworkers union. |

|

| |||||

| 1.75 (0.42–7.38) | 3 | 5 | Fritschi et al. [67] | Chlorophenoxys | |

|

| |||||

| 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 11 | 25 | Orsi et al. [70] | Phenoxys | |

|

| |||||

| 0.94 (0.67–1.33) | 49 | 187 | Hohenadel et al. [17] | 2,4-D | |

|

| |||||

| 1.78 (1.27–2.5) | 63 | 133 | Hohenadel et al. [17] | 2+ phenoxys | |

The strongest association between exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds and NHL is demonstrated through a series of occupational case-control studies carried out in Sweden [56, 60, 68, 71, 72, 90, 93, 94, 101–103]. These occupational studies focused on individuals involved in manufacturing chlorophenoxy compounds or professional sprayers, particularly in the forestry and railroad industries (e.g., spraying noxious weeds to maintain rights-of-way, etc.). The primary criticisms of these studies [104] include possible inaccurate diagnoses, observation and/or recall bias, lack of control for confounding variables, and poorly specified exposures (exposure is typically defined as greater than one day). Consequently, it is difficult to infer causality from these studies since there were numerous, largely statistically uncontrolled confounding exposures, and exposure itself was poorly specified, relying largely on self-reported questionnaires, and often without demonstrating dose-response relationships. For deceased cases, exposure categorization relied on next of kin, which may be particularly unreliable. Exposure was defined as greater than one day over many years.

These studies do not consistently demonstrate statistical significance or strength of association. For example, Hardell and Eriksson [60] conducted an analysis of a population-based case-control study in northern and middle Sweden with 404 NHL cases, 741 controls overall, and 12 NHL cases with 11 controls for the MCPA-specific analyses. They used questionnaires supplemented by telephone interviews to estimate exposure. They found a marginally statistically significant odds ratio for exposure to MCPA, but only when a latency period greater than 30 years was assumed. For other time periods, the association was not statistically significant. The odds ratio was less than 1.0 for exposure within 10–20 years of NHL onset, indicating reduced risk. Only the univariate analyses showed an increased OR = 2.7 (95% CI 1.0–7.0); the multivariate analysis OR = 1.2 (95% CI = 0.6–2.0). That is, only when exposures were individually modeled the authors did demonstrate statistical significance.

Another set of studies from the United States show more equivocal results. Hoar et al. [57] conducted a population-based, case-control study in Kansas based on telephone interviews with 200 white men diagnosed with NHL along with 1,005 controls. Use of chlorophenoxy herbicides (predominantly 2,4-D) in 24 cases and 78 controls was associated with an OR = 2.2 (95% CI = 1.2–4.1). Table 2 shows the results stratified by days per year use of 2,4-D, which shows that only the highest exposure was statistically significant, and the lowest exposure predicts a higher OR than the next two higher exposures. However, the number of cases and controls was very small when stratifying results. Zahm et al. [61] followed up with a population-based, case-control study in 66 counties in eastern Nebraska. Telephone interviews were conducted with 201 white men diagnosed with NHL between July 1, 1983 and June 30, 1986 with 775 controls. The authors report a 50% increase in NHL among men who mixed or applied 2,4-D (OR = 1.5, 95% CI 0.9–2.5). Reported ORs were largely unchanged when controlling for use of other pesticides and use of protective equipment. In fact, those farmers who reported typically using protective equipment had a higher OR (1.7, 95% CI = 0.9–3.1) as compared to those who did not (OR = 1.2, 95% CI = 0.6–2.4). It does not appear that the study controlled for smoking and/or other lifestyle factors. One issue to note with these studies is that the questionnaire used to determine exposure asked only about herbicide usage generally and therefore may not apply specifically to 2,4-D. Statistically significant associations were also found with triazines (OR = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.2–5.4), trifluralin (OR = 12.5, 95% CI = 1.6–116.1), and herbicides not otherwise named (OR = 5.8, 95% CI = 1.9–17.2).

Kogevinas et al. [59] report on a large, international, nested case-control study sponsored by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Kogevinas et al. [59] evaluated 11 soft-tissue sarcoma and 32 lymphoma cases occurring within an international cohort which were matched for age, sex, and country of residence with 55 and 158 controls, respectively. Three industrial hygienists who were blind to case-control status estimated exposures to 21 chemicals or mixtures. In this study, the results for NHL were not statistically significant and showed ORs less than one (Table 2). Predicted ORs did not show a dose-response relationship across exposures when expressed as referent, low, medium, and high (e.g., the lowest exposure, in some cases, had the highest predicted OR, but sample sizes were very small when defined this way). A strength of this study is the international scope, with cases and controls based on worldwide cohorts.

Other studies, particularly those that evaluated multiple exposures and/or dose-response relationships, do not demonstrate a convincing relationship between exposure and outcome. For example, Cantor et al. [64] report on a case (n = 622) control (n = 1245 population-based) study which evaluated potential exposures across a wide range of pesticides, herbicides, and insecticides and found statistically significant positive associations with exposure to malathion, DDT, chlordane, and lindane, but not chlorophenoxys (largely 2,4-D) and NHL. Similarly, McDuffie et al. [13] conducted a Canadian multicenter population-based incident, case (n = 517) control (n = 1506) study among men in a diversity of occupations using an initial postal questionnaire followed by a telephone interview for those reporting pesticide exposure of 10 h/year or more and a 15% random sample of the remainder. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were computed using conditional logistic regression stratified by the matching variables of age and province of residence, and subsequently adjusted for statistically significant medical variables (history of measles, mumps, cancer, allergy desensitization treatment, and a positive history of cancer in first-degree relatives). They found that among major chemical classes of herbicides, the risk of NHL was statistically significantly increased for exposure to phenoxy herbicides (OR = 1.38; 95% CI = 1.06–1.81), although a detailed evaluation of individual phenoxy herbicides found the highest individual OR for mecoprop (OR = 2.33; 95% CI = 1.58–3.44) rather than 2,4-D or MCPA. Moreover, across the entire study, the highest ORs were found for aldrin (OR = 4.18; 95% CI = 1.48–11.96). In their final models, NHL was most highly associated with a personal history of cancer; a history of cancer in first-degree relatives; exposure to dicamba-containing herbicides, to mecoprop, and to aldrin. Their final models did not include 2,4-D or MCPA.

Miligi et al. [58] conducted a population-based case-control study in Italy based on 1,575 interviewed cases and 1,232 controls in the nine agricultural study areas. Exposure to nitroderivatives and phenylimines among fungicides, hydrocarbon derivatives and insecticide oils among insecticides, and the herbicide amides were the chemical classes observed to be associated with developing NHL. ORs for the chlorophenoxy compounds are presented in Table 2 and are slightly elevated in some cases but all statistically insignificant. Exposure was assigned as a probability of usage in terms of chemicals families and active ingredients according to an ordinal scale (low, medium, and high) taking into account the time period, crops and crop diseases, and treatment applied as well as the area. Industrial hygienists reviewed questionnaire data on crop diseases, treatments carried out and historical periods, field acreage, geographical location, and self-reported use of specific pesticides. The agronomists involved in the pesticide exposure assessment based their judgments on personal local experience, national statistics on pesticide use per year and administrative unit, available records of local pesticide suppliers, records of pesticide purchases by the major farms, and on professional consultants for the different crops. Miligi et al. [58] report on several additional analyses that find a statistically significant OR = 4.4 (95% CI = 1.1–29.1) based on 9 cases and 3 controls related to 2,4-D usage without protective equipment. The wide confidence interval (e.g., small n) makes it difficult to infer a relationship.

In an “integrative” study evaluating many potential pesticides and combinations of pesticides, De Roos et al. [16] report on a pooled analysis from three case-control studies conducted under the auspices of the National Cancer Institute in the United States based on data from the 1980s. The authors used these pooled data to examine pesticide exposures in farming as risk factors for NHL in men. The large sample size (n = 3417) allowed analysis of 47 pesticides simultaneously, controlling for potential confounding by other pesticides in the model, and adjusting the estimates based on a prespecified variance to make them more stable. Reported use of several individual pesticides was associated with increased NHL incidence, including organophosphate insecticides coumaphos, diazinon, fonofos, insecticides chlordane, dieldrin, copper acetoarsenite, herbicides atrazine, glyphosate, and sodium chlorate. A subanalysis of these “potentially carcinogenic” pesticides suggested a positive trend of risk with exposure to increasing numbers. Estimated ORs for 2,4-D and MCPA were both below one (Table 2) and were not elevated nor significant in any combined model.

However, Mills et al. [12] in a study involving 131 lymphohematopeoitic cancers diagnosed in California between 1988 and 2001 in United Farm Workers of America (UFW) members found a statistically significant OR = 3.8 (95% CI = 1.85–7.81) for exposure to 2,4-D. This was the only statistically significant association for NHL across all pesticides studied. However, while the authors included age, sex, and length of union affiliation as covariates, there was no mention of controlling for smoking and/or other risk factors that may be associated with NHL. Exposure was characterized by linking UFW job histories (records kept by the union) to records of pesticide use by county kept by the State of California Pesticide Databank. Employment in a given crop in a given month/year in a given county was matched to the corresponding application of several pesticides on that crop in a given month and county location. These applications (in pounds of active ingredients applied) were summed and used as a proxy or surrogate measure of pesticide exposure for both cases and controls for the two- to three-decade period prior to diagnosis of the cancer. However, although exposure was better characterized than in most epidemiologic studies, there was no verification of any individual exposure (e.g., true individual exposures were completely unknown).

Orsi et al. [70] conducted a hospital-based case-control study in six centers in France between 2000 and 2004. The cases were incident cases with a diagnosis of lymphoma aged 18–75 years. During the same period, controls of the same age and sex as the cases were recruited in the same hospital, mainly in the orthopaedic and rheumatological departments. Exposures to pesticides were evaluated through specific interviews and case-by-case expert reviews. The authors calculated ORs and 95% CIs using unconditional logistic regressions and did not find an increased OR for occupational exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds as a class and NHL. Hohenadel et al. [17] report on the results of the cross-canada study of pesticides and health, a case-control study of Canadian men 19 years of age or older, conducted between 1991 and 1994 in six Canadian provinces (Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan). A combination of postal and telephone interviews were used to obtain data for covariates and for pesticide use. Stratifying respondents based on use of 2 or more chlorophenoxy herbicides showed a statistically significant OR = 1.78 (95% CI = 1.27–2.5). However, a model with only exposure to 2,4-D resulted in an OR <1, and in a larger evaluation of combinations of pesticides, malathion consistently emerged as a statistically significant exposure while 2,4-D did not.

All the previous studies have involved occupational exposures, which may not be particularly relevant to residential settings or the general public with respect to actual exposure levels in the population and potential risks associated with a significant use of chlorophenoxy compounds. One study, however, Hartge et al. [15] explored the relationship between residential use of herbicides (primarily on lawns) and NHL in a population case-control study across Iowa, metropolitan Detroit, Los Angeles, and Seattle from the period 1998 to 2000. The authors calculated relative risks based on measured 2,4-D in carpet dust (Table 2) as well as self-reported herbicide (specific chemicals not provided) use on lawns. The authors did not observe a relationship between estimates of exposure and NHL.

Another study, Leiss and Savitz [69] explored associations between home pesticide use and childhood cancers in a study that grew out of childhood cancer and electromagnetic field exposure in Colorado. Exposure data was collected through parental interviews and dichotomized as “any use” versus “no use” for each pesticide type and exposure period based on the question whether the yard around the residence was “ever treated with insecticides or herbicides to control insects or weeds.” No associations with lymphomas, broadly defined, were found with all predicted ORs less than one.

2.1.2. STS

The bottom portion of Figure 4 provides a summary of the available STS studies.

Hardell and Sandstrom [93] estimated an OR of 5.3 (95% CI = 2.4–11.5) for STS based 13 cases and 14 controls from the same Swedish case-control study as described previously for NHL. A follow-on study by Eriksson et al. [94] estimated an elevated although nonstatistically significant OR of 4.2 for chlorophenoxy exposures free from TCDD contamination (e.g., MCPA, 2,4-D, mecoprop, and dichlorprop). The New Zealand studies [98, 105] estimated a slightly elevated although nonstatistically significant OR in one study ([105], OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 0.8–3.2; 17 cases and 13 controls) and an OR less than one in another (Smith and Pearce [98]; OR = 0.7; 95% CI = 0.3–1.5; 6 cases and 46 controls).

Woods et al. [66] in a study in western Washington state estimated an OR = 0.8 (95% CI = 0.5–1.2) assuming predominantly chlorphenoxy exposures, and Cantor et al. [64] estimated a nonsignificant OR = 1.2 (95% CI = 0.9–1.6) based on 118 cases and 231 controls. Vineis et al. 1986 [106] in a study in Italy involving female rice weeders found a nonsignificant OR = 2.7 (95% CI = 0.59–12.37) based on 31 cases and 73 controls. Exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds (likely including 2,4,5-T) was based on three categories: no exposure, maybe exposed, and definitely exposed. Rice weeders were considered exposed to phenoxy herbicides when they worked after 1950 and did not work exclusively in a small rice allotment of their own. The “maybe” category was used particularly for people engaged in corn, wheat, and pasture growing after 1950.

Hoar et al. [57] conducted a population-based, case-control study in Kansas based on telephone interviews with 200 white men diagnosed with STS along with 1,005 controls. Estimated ORs were all below one except for 11 cases (57 controls) with greater than 16 years of exposure (OR = 1.4; 95% CI = 0.6–3.1).

The strongest associations between chlorophenoxy compound exposure and STS were found by Kogevinas et al. [59] based on 10 cases and 30 controls, who estimated an OR = 10.3 (95% CI = 1.2–90.6). When stratifying results by predominantly MCPA/MCPP exposures, the estimated OR increased to 11.27 (95% CI = 1.3–97.9) based on 10 cases and 29 controls and decreased to 5.72 but still statistically significant (95% CI = 1.14–28.7) based on 9 cases and 24 controls for exposures identified as predominantly 2,4-D related. Exposures to 21 chemicals or mixtures were estimated by three industrial hygienists who were blind to the subject's case-control status, but a dichotomous exposure classification was applied which likely included considerable misclassification (according to the authors page 398) since information on dates and quantities of production and spraying of the six pesticides was not consistently available. Results are presented for four exposure categories (none, low, medium, and high), and the predicted ORs for the chlorophenoxys and MCPA do not follow a dose-response relationship, while dose-response relationships were observed for TCDD, 2,4-D, and 3,4-5-T. However, results presented in this way were not statistically significant except for the highest predicted exposure for chlorophenoxys generally. The authors used a logistic model and developed results for each contaminant individually.

Another study, Leiss and Savitz [69] explored associations between home pesticide use and childhood cancers in a study that study that grew out of childhood cancer and electromagnetic field exposure in Colorado. Exposure data was collected through parental interviews, and dichotomized as “any use” versus “no use” for each pesticide type and exposure period based on the question whether the yard around the residence was “ever treated with insecticides or herbicides to control insects or weeds.” Separate ORs were estimated for exposure during the last three months of pregnancy (OR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.5–1.3 based on 10 cases and 79 controls), exposure between birth and two years of diagnosis (OR = 4.1; 95% CI = 1.0–16.0), and exposure between two years of diagnosis and diagnosis (OR = 3.9; 95% CI = 1.7–9.2).

The cohort studies do not show an association between exposure and STS as an outcome. Only two of the case control studies show statistically significantly increased ORs [59, 69]. Leiss and Savitz [69] focused on childhood STS, and exposure was only specified as “yard treatment.”

2.1.3. HD

The top portion of Figure 4 provides the results of the epidemiologic studies focusing on HD.

The Swedish studies [68, 90] show mixed results for HD as an endpoint. Persson et al. [68] estimated an OR = 3.8 (95% CI = 0.7–21) based on 4 cases and 6 controls for HD cases with exposure to predominantly chlorophenoxy compounds broadly defined. The only statistically significantly increased OR = 5.0 (95% CI = 2.4–10.2) based on 14 cases and 24 controls [90] was for a study for which exposure was categorized as at least one day of exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds based on a self-administered questionnaire. A latency period of at least five years was assumed by excluding all exposures within five years of diagnosis.

Hoar et al. [57] conducted a population-based, case-control study in Kansas based on telephone interviews with 173 white men diagnosed with HD with 1,007 controls. None of the estimated ORs for HD was statistically significant, and was only greater than one for greater than 16 years of exposure (OR = 1.2; 95% CI = 0.5, 2.6).

Finally, Orsi et al. [70] found a nonsignificant OR = 2.5 (95% CI = 0.8–7.7) based on 6 cases and 14 controls for occupational exposure of agricultural workers to chlorophenoxy compounds as a class for HD. This hospital-based case-control study obtained all cases of lymphoid neoplasms from the main hospitals of the French cities of Brest, Caen, Nantes, Lille, Toulouse, and Bordeaux between September 2000 and December 2004. Exposure was categorized first through a self-administered questionnaire and followed up by 90 minute individual face-to-face interviews.

2.1.4. Leukemia

The middle portion of Figure 4 provides the results of the studies investigating leukemia as an endpoint.

To investigate whether exposure to carcinogens in an agricultural setting is related to an increased risk of developing leukemia, Brown et al. [91] conducted a population-based case-control interview study of 578 white men with leukemia and 1245 controls living in Iowa and Minnesota. They found a slight, but significant, elevation in risk for all leukemia (OR = 1.2) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (OR = 1.4) for farmers compared to nonfarmers, but there were no significant associations with leukemia for exposure to specific herbicides (including 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T). However, significantly elevated risks for leukemia of >2.0 were seen for exposure to specific animal insecticides including the organophosphates crotoxyphos (OR = 11.1), dichlorvos (OR = 2.0), famphur (OR = 2.2), and the natural product pyrethrins (OR = 3.7), and the chlorinated hydrocarbon methoxychlor (OR = 2.2). There were also smaller, but significant, risks associated with exposure to nicotine (OR = 1.6) and DDT (OR = 1.3). Based on exposure 2,4-D alone, Brown et al. [91] estimated an OR = 1.2 (95% CI = 0.9–1.6) based on 98 cases and 227 controls, and for MCPA, the estimated OR = 1.9 (95% CI = 0.8–4.3) based on 11 cases and 16 controls.

Leiss and Savitz [69] found no associations between 2,4-D use and leukemia with all predicted ORs less than one.

Orsi et al. [70] did not find an increased OR when evaluating leukemia broadly, but disaggregated by subtype, found an increased OR = 4.1 (95% CI = 1.1–15) for hairy cell leukemia, specifically, based on 4 cases and 20 controls. The overall OR = 1.0 (95% CI = 0.4–2.5) based on 7 cases and 20 controls largely exclusively exposed to chlorophenoxy compounds. This hospital-based case-control study obtained all cases of lymphoid neoplasms from the main hospitals of the French cities of Brest, Caen, Nantes, Lille, Toulouse, and Bordeaux between September 2000 and December 2004. Exposure was categorized first through a self-administered questionnaire and followed up by 90 minute individual face-to-face interviews.

Van Maele-Fabry et al. [44] conducted a meta-analysis focused on three cohort studies published between 1984 and 2004 found a statistically significant odds ratio (OR) for exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds and leukemia (OR = 1.60, 95; confidence interval (CI) = 1.02–2.52), although all three underlying studies individually showed nonsignificant associations ([86, 92, 113]—factory B only).

Agricultural risk factors for lymphohematopeoitic cancers, including leukemia, in Hispanic farm workers in California were examined in a nested case-control study embedded in a cohort of 139,000 ever members of a farm worker labor union in California [12]. Risk of leukemia was associated with exposure to the pesticides mancozeb (OR = 2.35; 95% I = 1.12–4.95) and toxaphene (OR = 2.20; 95% CI = 1.04–4.65) but not 2,4-D (OR = 1.03; 95% CI = 0.41–2.61).

2.2. Cohort Studies

The cohort studies, Table 3, by their design, evaluate all cancers simultaneously rather than focusing on particular cancers as is often found in the case-control studies. Table 3 presents the results of the major cohort studies and in general show few statistically significant associations except for two [89, 111]. The Carrao et al. [111] cohort consisted of 25,945 male farmers licensed between 1970 and 1974 to buy and use pesticides without any further refinement of what pesticides were used, how often, and in what quantities. They estimated a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.4 (95% CI = 1.0–1.9) across the category “all malignant lymphomas” (which considers all the lymphohematopoietic cancers as a single category) and conclude that this is likely due to exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds. The rationale for this is that first, because the higher incidence was only found in predominantly arable areas, where, the authors argue, greater use is made of herbicides (although the specific herbicides in use are not discussed, and the assumption is that these herbicides are largely chlorophenoxys with no justification), and second, the authors argue that the use of chlorophenoxy acid products had increased in recent years, so much so that this must represent the predominant exposure. It is therefore difficult to argue that this analysis shows much support for a relationship between exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds and lymphoma.

Table 3.

Cohort studies.

| Reference | Metric | HD | STS | NHL | Leukemia | Exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lynge [107] | SIR | Lymphoma = 1.1 | 2.72 | Lymphoma = 1.1 | 1.3 | Chlorophenoxy manufacturing workers; confidence intervals not provided |

|

| ||||||

| Wiklund et al. [96, 108, 109] | SIR | NR | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | NR | NR | MCPA, but including TCDD and other chlorophenoxy exposures |

|

| ||||||

| Wiklund et al. [76] | SIR | 1.2 (0.6–2.16) | NR | 1.01 (0.63–1.54) | NR | Chlorophenoxy, but including TCDD and other exposures |

|

| ||||||

| Wiklund et al. [77] | SIR | 1.02 (0.88–1.88) | NR | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) | NR | Chlorophenoxy, but including TCDD and other exposures |

|

| ||||||

| Bond et al. [110] | SMR | All lymphomas 2.02 (0.06–4.6) | 2.2 (0.03–7.9) | 2,4-D manufacturing | ||

|

| ||||||

| Wiklund et al. [78] | SIR | 1.2 (0.6–2.16) | 0.94 (0.34–2.04) | 1.01 (0.63–1.54) | 0.66 (0.28–1.21) | MCPA dominates but many other compounds also |

|

| ||||||

| Corrao et al. [111] | SIR | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) (all lymphomas, including NHL, HD) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | Assumed chlorophenoxy | ||

|

| ||||||

| Wigle et al. [80] | SMR | NR | 0.89 (0.53–1.40) | 0.92 (0.75–1.11) | 0.88 (0.74–1.04) | Chlorophenoxy |

|

| ||||||

| Coggon et al. [81] | SMR | 0 (0.–9.76) | 0 (0–20.58) | 2.72 (0.33–9.73) | NR | Chlorophenoxy |

|

| ||||||

| Bloemen et al. [112] | SIR | NR | NR | 2.0 (0.2–7.1) | NR | 2,4-D manufacturing; update to Bond [110] |

|

| ||||||

| Asp et al. [82] (10 yr latency) | SIR | 1.18 (0.03–6.56) | None observed | 0.42 (0.01–2.35) | 1.23 (0.25–3.59) | Chlorophenoxy sprayers |

|

| ||||||

| Kogevinas et al. [83] | SMR | 0.99 (0.48–1.82) | 2.00 (0.91–3.79) | 1.27 (0.88–1.78) | 1.00 (0.69–1.39) | Chlorophenoxy and chlorophenols |

|

| ||||||

| Zahm [74] | SMR | NR | NR | 1.14 (0.31–2.91) | NR | Lawn applicators; 4 deaths |

|

| ||||||

| Lynge [86] | SIR | NR | 1.62 (0.4–4.1) | 1.10 (0.4–2.6) | 1.21 (0.49–2.50) | Mostly MCPA, MCPP, some 2,4-D, and 2,4,5-T |

|

| ||||||

| Burns et al. [79] | SMR | 1.54 (0.04–8.56) | NR | 1.00 (0.21–2.92) | 1.30 (0.35–3.32) | 2,4-D manufacturing; Update to Bond [110]; Bloemen [112] |

|

| ||||||

| 'T Mannetje et al [84] | SMR | 0 (0.–16.1) | 4.28 (0.11–23.8) | 0.69 (0.02–3.84) | 1.16 (0.03–6.44) | Chlorophenoxy sprayers, include dioxin, paraquat, and organophosphates |

|

| ||||||

| 'T Mannetje et al [84] | SMR | 5.58 (0.14–31.0) | 0 (0–19.3) | 0.87 (0.02–4.87) | 0 (0–5.29) | Production workers |

|

| ||||||

| Jones et al. [89] | SMR | 1.15 (0.74–1.78) | 0.96 (0.62–1.49) | 2.01 (1.38–2.93) | 1.02 (0.707–1.463) | Chlorophenoxy manufacturing, but many with predominantly 2,4,5-T known to be contaminated with dioxin; meta-analysis of 20 studies |

|

| ||||||

| Boers [85] Factory A | SMR | NR | NR | 0.92 (0.19–4.47) | 0.28 (0.03–2.61) | Chlorophenoxy, solvents |

|

| ||||||

| Boers [85] Factory B | SMR | NR | NR | only one case | 1.53 (0.22–10.82) | MCPP, MCPA, and 2,4-D |

|

| ||||||

| Burns et al. [79] | SIR | 0.97 (0.01–5.4) | 0.6 (0.01–3.3) | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) | 0.9 (0.4–1.8) | 2,4-D manufacturing; 1985–2007 cohort 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Burns et al. [79] | SIR | 1.05 (0.01–5.9) | 0.7 (0.01–3.6) | 1.4 (0.7–2.3) | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 2,4-D manufacturing; 1985–2007 cohort 2 |

|

| ||||||

| Burns et al. [79] | SIR | 1.3 (0.02–7.2) | 0.8 (0.01–4.5) | 1.7 (0.9–2.9) | 0.9 (0.3–2.0) | 2,4-D manufacturing; 1985–2007 cohort 3 |

SIR: standardized incidence ratio.

SMR: standardized mortality ratio.

The Jones et al. [89] study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of cohorts of workers in the crop protection product manufacturing industry. Jones et al. estimated meta SMRs based on 20 individual studies and found a statistically significantly increased SMR for lymphoma, broadly defined, and exposure to chlorophenoxys (SMR = 2.01; 95% CI = 1.38–2.93) [89]. Although the SMR for HD was greater than one, it was not statistically significant. A limitation of this meta-analysis is that the underlying studies included all chlorophenoxy compounds, including 2,4,5-T, which, as acknowledged by the authors, is likely to have been contaminated with dioxin.

There have been a series of studies exploring cancer mortality and/or incidence rates in a cohort of 2,4-D manufacturing workers from the Dow Chemical Company in Midland, MI, USA [75, 79, 110, 112]. In the first of these, Bond et al. [110] estimated standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) for 878 chemical workers potentially exposed to 2,4-D at anytime between 1945 and 1983. Observed mortality was compared with expected levels based on adjusted rates for United States white men and for other male employees from a manufacturing location who were not exposed to 2,4-D. Analyses by production area, duration of exposure, and cumulative dose showed no patterns suggestive of a causal association between 2,4-D exposure and any other particular cause of death. Similarly, follow-up studies have not provided evidence that exposures in manufacturing workers have led to increased risks.

Wiklund et al. [78] report on a cohort consisting of 20,245 subjects (99% men; 1% women) who had a license for pesticide application issued between 1965 and 1976 in Sweden. Approximately 20% of subjects reporting using herbicides during the 1950s: 51% for the 1960s and 68% for the 1970s. The most commonly used herbicide across all three decades was MCPA. The authors found a decreased relative risk across all cancers.

Bond and Rossbacher [39] report on two studies based on cohorts that manufactured MCPA. The first, Lynge [107] evaluated 4459 chemical workers from two of four companies that had produced phenoxy herbicides in Denmark, although these workers were also engaged in the manufacture of diverse chemical products including not only herbicides but dyes and pigments as well. Roughly one third of them (n = 940) had been assigned to phenoxy herbicide production or packaging. MCPA and MCPP were the predominant phenoxy herbicides produced, followed by 2,4-D and 2,4-DP. Five cases of soft-tissue sarcoma were reported among the men as compared to expected (relative risk = 2.7; (95% confidence interval) 0.88–6.34) and no cases among the women. A slight deficit of total cancer was noted among the combined group of chemical workers. The second, Coggon et al. [92] examined mortality and cancer incidence in 5784 men who had been employed in manufacturing or spraying MCPA in the United Kingdom. Workers were classified according to their potential for exposure into high, low background based on their job titles. Overall mortality in the cohort was less than that expected from national death rates, as was mortality from all neoplasms, heart disease, and diseases of the respiratory system. Only one death from soft-tissue sarcoma occurred compared with one expected. Three men died from malignant lymphoma compared with nine expected.

Lynge [86] conducted a follow-up cohort study of 2119 workers from Denmark employed at two factories that produced phenoxy herbicides since 1947 and 1951, respectively. From 1947 to 1993 the 2119 workers showed a slightly lower overall cancer incidence than the Danish population (observed = 204; expected = 234.23; SIR = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.8–1.0). Four soft-tissue sarcoma cases were observed (expected = 2.47; SIR = 1.62; 95% Cl = 0.4–4.1). There were six cases of NHL (expected = 5.07; SIR = 1.10; 95% CI = 0.4–2.6) and no significantly elevated risk of other cancers. A follow-up study by Coggon et al. [81] in 2239 men employed in the United Kingdom from 1963 to 1985 observed two deaths from NHL with 0.87 expected, a difference that was not statistically significant. No cases of STS or HD were recorded.

In a cohort study published in 2005, 'T Mannetje et al. [84] followed 813 phenoxy herbicide producers 699 sprayers from January 1, 1969 and January 1, 1973, respectively, until December 31, 2000. The authors calculated SMRs using national mortality rates and found a 24% nonsignificant excess cancer mortality in phenoxy herbicide producers, with a significant excess for multiple myeloma. Associations were stronger for those exposed to multiple agents including dioxin during production. Overall cancer mortality was not increased for producers and sprayers mainly handling final technical products.

Burns et al. [79] conducted a cohort study of male employees of The Dow Chemical Company who manufactured or formulated 2,4-D anytime from 1945 to the end of 1994. Their mortality experience was compared with national rates and with more than 40,000 other company employees who worked at the same location. There were no significantly increased SMRs for any of the causes of death analyzed. When compared with the United States rates, the SMR for NHL was 1.00 (95% CI = 0.21–2.92).

Boers et al. [85] report on a third follow-up of a retrospective cohort study involving two chlorophenoxy herbicide manufacturing factories, producing mainly 2,4,5-T (factory A) and MCPA/MCPP (factory B) found no statistically significant increases in lymphohematopoietic cancer deaths, although SMRs were greater than one.

Aside from agricultural and forestry uses of 2,4-D, the lawn care industry also uses 2,4-D. Zahm [74] conducted a retrospective cohort mortality study of 32,600 employees of a lawn care company and found four deaths due to NHL (SMR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.31–2.91). Two of the (male) applicators had been employed longer than three years, and for those, the predicted SMR was 7.11 (95% CI = 1.78–28.42). Risks of NHL increased for male applicators, especially those employed for three or more years, but no quantitative or semiquantitative measures of pesticide use or exposure were presented.

2.3. Summary of Epidemiologic Studies

Associations between exposures to chlorophenoxy compounds (including 2,4-D and MCPA) and potential outcomes have generally been developed through occupational studies in manufacturing facility workers and/or agricultural workers. Many of the underlying studies suffer from poor exposure specification (e.g., not clear which phenoxy herbicides were actually used and/or manufactured, whether there was cross-contamination from dioxin or other constituents, and actual exposures and doses experienced by cases and/or cohorts); poor covariate control (e.g., smoking status); insufficient sample sizes; insufficient follow-up for the cohort studies. Nonetheless, the results of the reviews are equivocal, with some suggesting an association with NHL but others not, and most indicating that an association with STS, HD, and/or leukemia is weak at best given the generally observed lack of statistical significance and risk measures less than one. Those studies that included more realistic exposures (e.g., a variety of pesticides, etc.) tended to reduce the influence of 2,4-D and/or MCPA than those studies considering only chlorophenoxy exposure alone. The few studies available for exposures likely to be experienced by the general public and/or residential use of 2,4-D and MCPA found no associations with health outcomes.

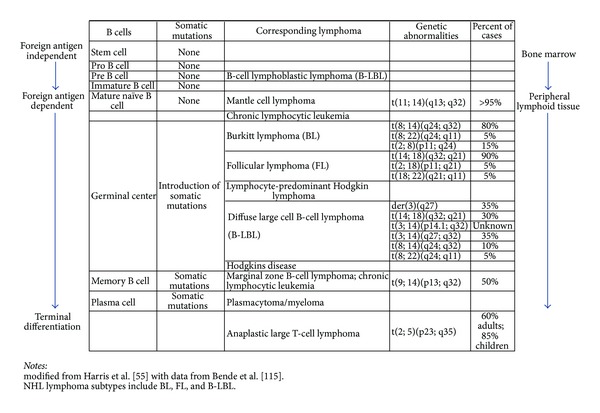

The way in which diseases are grouped and categorized plays an important role in epidemiological studies. Sorting results by histological subtype can lead to small numbers and reduced power, increasing the probability of finding a particular association simply by chance. However, there may be important differences with respect to exposure in terms of disease outcome (e.g., exposure to a particular causal agent leads to only one histological subtype). Many different types of groupings have been used in analyzing epidemiologic data, primarily reflecting the classification system in use at the time of diagnosis or cause of death, and a confounding factor is that these classifications change over time. Our understanding of disease etiology is always growing, and increasingly researchers are able to identify key molecular and cellular transformations required for disease progression. This introduces a challenge for epidemiologic studies in that it may not be appropriate to consider all histological subtypes of a particular carcinogenic outcome relative to a hypothesized exposure (and by extension, mode of action), or it may be possible to incorporate cellular changes into measures of exposure and/or effect in epidemiologic studies (discussed in the next section). Table 4 provides a summary of the available epidemiologic studies that have evaluated potential exposures and NHL outcomes by subtype and shows that a consistent relationship between exposures and outcomes defined by histological subtypes does not emerge.

Table 4.

Epidemiologic studies by histological subtype for NHL.

| Type of lymphoma | Number exposed | Chlorophenoxys | MCPA | 2,4-D and/or 2,4,5-T | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-cell lymphomas total | 819 | 1.99 (1.2–2.32) | 2.59 (1.14–5.91) | 1.69 (0.94–3.01) | Eriksson et al. [71] |

| 665 | 1.47 (0.33–6.64) | Fritschi et al. [67] | |||

|

| |||||

| Lymphocytic | 196 | 2.11 (0.99–4.47) | 2.57 (0.74–8.97) | 1.93 (0.85–4.41) | Eriksson et al. [71] |

|

| |||||

| Follicular | 165 | 1.26 (0.42–3.75) | — | 1.21 (0.35–4.22) | Eriksson et al. [71] |

| 227 | 1.15 (0.12–11.2) | Fritschi et al.[67] | |||

| 27 | 0.8 (0.2–3.6) | Orsi et al. [70] | |||

|

| |||||

| Diffuse large B cell | 239 | 2.6 (1.08–4.33) | 3.94 (1.48–10.5) | 1.65 (0.71–3.82) | Eriksson et al. [71] |

| 231 | 2.16 (0.36–13.1) | Fritschi et al. [67] | |||

| 30 | 1.0 (0.4–2.8) | Orsi et al. [70] | |||

|

| |||||

| Other specified B cell | 131 | 2.60 (1.20–5.64) | 3.2 (0.95–10.7) | 2.21 (0.9–5.44) | Eriksson et al. [71] |

|

| |||||

| Unspecified B cell | 89 | 1.14 (0.33–3.95) | 1.35 (0.16–11.2) | 0.88 (0.2–3.92) | Eriksson et al. [71] |

|

| |||||

| T cell | 53 | 1.62 (0.36–7.25) | 2.4 (0.29–20) | 1.02 (0.13–7.95) | Eriksson et al. [71] |

|

| |||||

| Unspecified NHL | 38 | 3.75 (1.16–12.1) | 9.31 (2.11–41.2) | 3.21 (0.85–12.1) | Eriksson et al. [71] |

Hoar et al. [57] reported no differences in the ORs associated with herbicide use when cases were categorized by histological subtype (specific results not reported).

Hardell et al. [56] reported no differences in the ORs associated with herbicide use when cases were categorized by histological subtype (specific results not reported).

In summary, the available epidemiologic studies are as follows.

-

Show inconsistent relationships between exposure to chlorophenoxy compounds generally, 2,4-D and/or MCPA specifically, and lymphohematopoietic outcomes.

- Strongest association is for NHL based on case-control studies.

- No statistically significant associations for leukemia.