Abstract

Adaptation can shift what individuals identify to be a prototypical or attractive face. Past work suggests that low-level shape adaptation can affect high-level face processing but is position dependent. Adaptation to distorted images of faces can also affect face processing but only within sub-categories of faces, such as gender, age, and race/ethnicity. This study assesses whether there is a representation of face that is specific to faces (as opposed to all shapes) but general to all kinds of faces (as opposed to subcategories) by testing whether adaptation to one type of face can affect perception of another. Participants were shown cartoon videos containing faces with abnormally large eyes. Using animated videos allowed us to simulate naturalistic exposure and avoid positional shape adaptation. Results suggest that adaptation to cartoon faces with large eyes shifts preferences for human faces toward larger eyes, supporting the existence of general face representations.

Introduction

Personal beauty affects many facets of our lives. We attribute a wide array of positive qualities, such as being more occupationally and interpersonally competent, better adjusted, and having greater social appeal, to attractive people and their opposites to unattractive people (Dion et al 1972; Feingold 1992; Langlois et al 2000). Given the importance of these judgments, we might ask how we make judgments on attractiveness.

Some aspects of attractiveness appear e universal. Cross-cultural studies show that individuals from different cultures agree on which faces in a set are more attractive (Bernstein et al 1982; Cunningham et al 1995; Geldart et al 1999; Perrett et al 1994). Furthermore, developmental studies show that young babies look longer at faces rated as attractive by adults than at those rated as unattractive (Geldart et al 1999; Langlois et al 1993; Samuels et al 1994; Slater et al 1998). Among the attractiveness criteria identified as universal are averageness, symmetry, and sexual dimorphism (Langlois and Roggman 1990; Möller and Swaddle 1997; Thornhill and Gangestad 1999).

Although there is extensive evidence for universal factors of attractiveness, there are also systematic differences in preferences between individuals, which reflect differences in experience. For instance, Martin (1964) found that while both African-American and Caucasian men considered Caucasian features to be more attractive than African features in the U.S., the same evaluation conducted in Nigeria showed a preference for African facial features. Furthermore, Bronstad and Russell (2007) show that close relations share even greater agreement on facial attractiveness than strangers from the same race or culture.

The effects of face adaptation have also been shown extensively in laboratory studies. Peskin and Newell (2004) demonstrated that increasing exposure to certain faces and thereby increasing the familiarity of those faces increased their attractiveness to participants. More specifically, Rhodes et al. (2003) showed that adaptation to consistent facial distortions shifted the participants’ judgment for what was most attractive toward the distortion. For instance, after repeated exposure to faces with wide noses, subjects will report faces with wider noses as more attractive. Cooper and Maurer (2008) showed similar effects with the vertical position of features on a face.

If human representation of faces is organized in a multidimensional “face space” centered on a prototypical face that represents the mean of a person’s experience, faces are judged by proximity to the prototypical face (Valentine 1991). Adaptation to a consistent distortion has been suggested to shift the prototypical face toward the adapting distortion (Leopold et al 2001; Leopold et al 2005; Rhodes et al 2003; Rhodes et al 2004; Webster et al 2004). Neuroimaging evidence supports this view, finding increased signal from the fusiform face area with increased variation from the mean face (Loffler et al 2005). Moreover, a shift in neural tuning was proposed to produce a shift the position of the mean face.

However, it is assumed that these studies done in controlled lab settings in fact reflect real world exposure and explain real world differences in preferences for faces. We test the validity of this assumption in this study by using a more naturalistic but still controlled tool for adaptation: videos. This offers a more naturalistic exposure because the position and size of the adapting faces changes dynamically, because accompanying speech and movement enhance life-like qualities, and because watching videos/television itself is common behavior.

Moreover, there are key caveats to past findings. Specifically, Xu et al (2008) found that adaptation to concave curves led subjects to perceive faces as happy more frequently while adaptation to convex curves led subjects to perceive faces as sad more frequently. However, the curves had to be positioned in the same spatial location as the mouths of the faces for this effect to occur, meaning that the effect is a result of low-level shape adaptation.

Furthermore, aftereffects of adaptation to distorted images of faces occur only within subcategories of the higher order construction of “face,” including age, gender, race/ethnicity, species, and even more transient features like expression and uprightness (Jaquet et al 2007; Little et al 2008; Rhodes et al 2007; Rhodes et al 2003; Webster et al 2004). For instance, Little et al (2008) had participants adapt to faces differing in eye spacing (wide or narrow) for European versus African faces. Adaptive face aftereffects occurred only within racial subcategories. Neuroimaging evidence suggesting that there are different neural populations responding to different subcategories within face space are consistent with this finding (Loffler et al 2005).

The question arises: is there a representation of a face that is distinct from basic shapes but more fundamental than the sub-categories of faces? While it might seem obvious that this general face representation exists, particularly given that the category of “face” exists in our language, the concept of the “uncanny valley” proposed by Mori (1970) suggests this may not be the case. Mori proposed a curve to show the relationship between peoples’ positive responses to an object and the humanness of that object. He suggested that as human-like features increase, people respond more positively to the object. However, at a distinct point, the curve dramatically dips into the “uncanny valley,” a region where the deviations from humanness are stronger than the reminders of humanness, so a feeling of uncanniness overcomes familiarity, and people respond with repulsion (figure 1). This points to a divide between human faces and other groups of faces and suggests that there is not a common fundamental representation of faces.

Figure 1.

Mori’s “Uncanny Valley”. Familiarity and positive feelings increase with increasing human likeness until it reaches the uncanny valley where the imperfections cause a feeling of strangeness and repulsion. As we approach a normal human, the positive feelings rise again.

In this study we assess whether there is a general representation of faces by testing if adaptation to cartoon faces can have effects across not just subcategories of faces but across the more general category of faces, from cartoon to human. The fact that faces in videos appear in different locations assures that adaptation effects cannot be attributed to low-level shape adaptation but instead would indicate face specific adaptation. Participants were exposed to cartoon videos containing characters with very large eyes. Before and after the adaptation phase, we presented human faces and asked participants to rate them for attractiveness.

If adaptation to cartoon faces does in fact affect attractiveness ratings for human faces, we expect adaptation to shift individual preferences toward the distortion such that participants rate faces with larger eyes as more attractive after adaptation compared with before. This would suggest that adaptation in a laboratory setting does in fact generalize to a more naturalistic setting to explain real world differences in preferences and that adaptation can cross categories of faces. Generally, this may also suggest that we have a basic representation of a face specific to faces but general to all kinds of faces.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 45 Harvard students, 14 males and 31 females, between the ages of 17 and 25 (M = 19.26, SD = 1.61) who consented to participating in the study and self identified as having no exposure to Japanese animation before participating in the study. We included only individuals with no prior exposure in order to assure a more homogeneous background experience amongst subjects to the adaptation stimuli. Participant ethnicity included 25 Caucasian, 9 Asian, 6 African/African American, 4 Hispanic, and 1 Mediterranean individuals. All were recruited from Harvard University through the study pool and received course credit for participation.

Participants were assigned to two groups generally matched for gender and ethnicity (not for age because of the small range); one group was exposed to anime cartoons, and the other was exposed to a live action video with real actors.

Stimuli

Adaptation Stimuli

The test group watched a 50-minute cartoon video – the first two episodes of the Japanese animation series “Fruits Basket”. The control group viewed a 50-minute live action video with real actors – the first episode of the television series “Heroes”.

Both videos included presentation of both male and female faces for almost the entirety of the 50 minutes. Both shows presented 7 female faces, not including background extras; “Heroes” presented 12 male faces and “Fruits Basket” presented 5. Though the number of male faces presented was incongruous across the two shows, this was not considered an issue because the test stimuli were all female faces. In terms of ethnicity, “Heroes” presented actors of all different ethnicities, and the cartoon characters in “Fruits Basket” were of undefined ethnicity, having various shades of hair and eye color and no distinct ethnic features. Furthermore, both shows have a storyline about the lives of individuals with supernatural abilities that are both gifts and curses, though “Heroes” has a darker emotional tone than “Fruits Basket”.

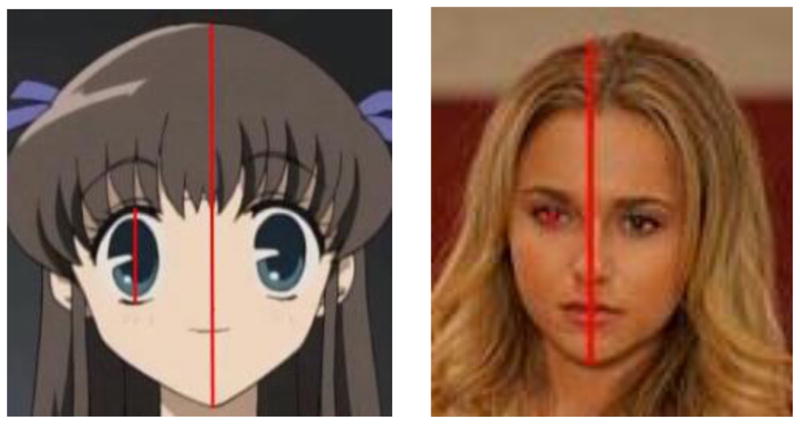

To compare relative eye size between videos, the ratio of the length and width of the eyes to those of the head were measured from screenshots. Three of the most viewed characters of each gender from both of the shows were used for comparison. For females, the average eye to head length ratio for the animated characters in “Fruits Basket” (M=0.18) was almost four times greater than the ratio for the actors in “Heroes” (M=0.05). The average width ratio was essentially the same (M=0.21 for animated, M=0.23 for live action). For males, the average length ratio for animated characters (M=0.11) was almost 3 times greater than that of the actors (M=0.04). As with females, the male width ratio was comparable (M=0.31 for animated, M=0.21 for live action).

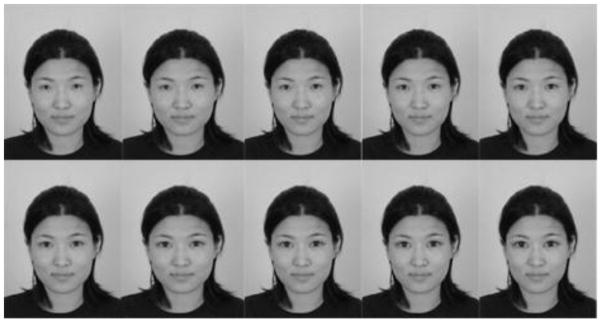

Test Stimuli

Participants were asked to rate for attractiveness a series of human faces with different eye sizes before and after adaptation. The set of stimuli consisted of 120 images of female faces viewed from the front with neutral expressions in identical conditions. Sixty of the images were faces with different eye sizes created from 6 photographs of different females faces of Asian and Caucasian race/ethnicity. For each of the 6 distinct faces, 10 face stimuli were created with systematic distortion in the size of the eyes. The original photographs were drawn from the set in Russell (In Press). They were altered using Photoshop to yield two different images, one with eyes that were 80% of the original size and one with eyes that were 120% of the original size. The two images were then morphed together in increments to yield ten images of each of the faces with systematically different eye sizes. These images were labeled 0–9 with 0 being 80% of the original size and 9 being 120% of the original size. All other aspects of the photographs were kept constant. The original photographs were not used in order to prevent possible bias toward the “natural” face over altered versions.

Sixty other images from the set of photographs in (Russell In Press) were included to obscure the purpose of the study. The faces were shown in 10 blocks of the following pattern: face 1 eye variation, other face, face 2 eye variation, other face, face 3 eye variation, other face, face 4 eye variation, other face, face 5 eye variation, other face, face 6 eye variation, other face. The specific eye variation in each set was randomly assigned. Each image was shown once, and all participants viewed the images in the same order. Each photo was 192 pixels in width and 256 pixels in height.

Procedure

All participants were first asked to fill out a questionnaire to determine previous exposure to Japanese animation. A mixed factorial design was then implemented. Participants were assigned to one of two adaptation groups (cartoon or live action) matched for gender and ethnicity. The cartoon group was assigned to watch the 50-minute cartoon video, and the live action group was assigned to watch the 50-minute live action video. Both groups rated test stimuli for attractiveness on a scale of 1 (Unattractive) to 7 (Attractive) before and after watching the show. The amount of time between when participants viewed the videos and when they rated the faces was about 1–2 minutes, during which time they received instructions.

The experiment was run on 24″ iMacs. Programming was done using PHP and hosted on a protected server. Morphman was used to create test stimuli images. Microsoft Excel and SPSS 16.0 were used to organize and process the data collected.

Results

The data collected were analyzed using similar methods to experiment 1 of Rhodes et al (2003). For each participant, ratings for all faces with the same incremental eye size were averaged together. Third order polynomials were fitted to each participant’s data and used to estimate the eye distortion level of the most attractive faces through finding the local maxima of the polynomial curves. Third order polynomials were used specifically because second order curves may be restrictive in shape and fourth order or higher curves possess more complexity than necessary.

Data from specific raters were excluded if the polynomial curve fit was poor and as a result did not provide any meaningful information. In the cartoon group, there were 22 participants; 19 participants’ data were included with average R2 = 0.91 and 3 were excluded. In the live action control group, there were 23 participants; 18 participants’ data were included with average R2 = 0.83 and 5 were excluded. The excluded participants had an average R2 = 0.35.

We conducted a two-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with adapting condition (cartoon or live action) as a between-participants factor and the mean distortion levels of the most attractive faces as a repeated measures factor. The interaction was significant, F(1, 37) = 6.45, p = 0.02. As predicted, the most attractive face shifted toward the adapting distortion of larger eyes after adaptation to cartoon faces. Gender and ethnicity were included as covariates and were found to be insignificant. When excluded subject data where the distortion level for the most attractive face could be identified were included in the analysis, the interaction was still significant (p<0.05). However, we felt that in those excluded cases, this method of analysis was not appropriate because the polynomial fit was not suitable for the data points.

Planned comparisons showed no initial difference in preference for eye sizes between groups prior to video adaptation (t(35) = 0.44, p = 0.67). In the test group that viewed cartoons, participants preferred faces with larger eyes after adaptation (M = 5.96, SD = 1.57) compared to before (M = 5.63, SD = 1.54) (t(18) = 2.12, p = 0.04), showing a significant shift toward the adaptive distortion (figure 3). This shift is seen for each of the six unique faces. In contrast, in the control group that viewed the live action show, there was no significant change in eye size preference after adaptation (M = 4.87, SD = 1.15) compared with before (M = 5.43, SD = 1.27) (t(17)= −1.75, p = 0.10). Descriptive statistics are shown below (table 1).

Figure 3.

An example of a set of stimuli with systematically varied eye size. They were created by incrementally morphing together the face with eyes 80% (0, upper left) of the original size and the face with eyes 120% (9, bottom right) of the original size. Participants viewed full color images.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics. (a) shows the means and standard deviations of the most attractive distortion for the test and control groups before and after watching videos. (b) shows the results from planned within group comparisons before and after adaptation.

| (a) Data summary by group

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | ||||

|

| |||||

| Sample Size | Mean | SDa | Mean | SDa | |

| Cartoon | 19 | 5.63 | 1.54 | 5.96 | 1.57 |

| Live Action | 18 | 5.43 | 1.27 | 4.87 | 1.15 |

| (b) Planned Within Group Comparisons

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (After-Before) | t | df | p | |

| Cartoon | 0.33 | 2.12 | 18 | 0.04* |

| Live Action | −0.56 | −1.75 | 17 | −0.10 |

Note. Mean values are from a 10-point scale (0 = 80% of original eye size, 9 = 120%).

Standard deviation

Alpha level was set at 0.05

Also, all individuals preferred faces with larger than normal eyess, which corresponds with past findings suggesting that larger eyes are considered more attractive in female faces (Geldart et al 1999).

Overall, these results expand on previous findings that adaptation to distorted human faces affects preferences for novel human faces (Cooper and Maurer 2008; Peskin and Newell 2004; Rhodes et al 2003) by showing that adaptation to cartoon faces can also affect preferences for human faces.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that adaptation to cartoon faces with large eyes shifts preferences for human faces toward larger eyes. It extends findings from past research on face adaptation in two ways. First, this study uses dynamic stimuli rather than static pictures, thus ruling out concerns about low-level retinotopic adaptation. Consequently we can more confidently generalize the effects found in controlled laboratory settings to experiences in everyday life.

Secondly, past research found adaptive shifts in human faces to affect perception only within subcategories of faces such as race/ethnicity, age, and gender (Jaquet et al 2007; Little et al 2008; Rhodes et al 2007; Rhodes et al 2003; Webster et al 2004). Our study suggests the possibility of cross category adaptation not just across human ethnicity, but across the more general category of face, from cartoon to human faces. The use of video precludes the possibility that the effect resulted from low-level shape adaptation as shown by Xu et al (2008). Furthermore, these findings support the idea of a representation that is specific to faces, yet general to different kinds of faces.

In addition, this study suggests that adaptation to cartoon faces can cross Mori’s “uncanny valley” to affect preferences for human faces. It is possible that the “uncanny valley” phenomenon actually stems from category ambiguity. Faces that are easily categorized can be more fluently processed, which has been shown to elicit more positive reactions (Reber et al 2004). Faces and other representations that fall into the “uncanny valley” may be difficult to categorize, hence less fluently processed, and thus induce more negative reactions.

Finally, the findings from this study may have implications for media effects on preferences. Popular media has been shown to affect viewers’ perceptions of beauty (Groesz et al 2002),. Young people spend on average 16–17 hours viewing television weekly beginning as early as age 2 (Nielsen Media Research 1998), and cartoons are a key part of this media diet. That cartoons can change real-life preferences extends the scope of impact from various media sources.

Figure 2.

Screenshots of one of the main female characters from the animated show and the live action show, representing characters of comparable age. The lines represent measurements used to approximate the ratios of eye to head length. The cartoon face has a ratio about 4 times that of the human face.

Figure 4.

Mean attractiveness ratings as a function of eye size for the two groups before and after viewing videos. Ratings were made on a scale of 1 (unattractive) to 7 (attractive). There is a significant shift in preferences toward faces with larger eyes after adaptation to cartoons (a) but no significant difference in participants who viewed the live action show (b).

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Deniz Kural for his assistance with task programming, and Shelley Carson for consultations throughout the project. This research was supported in part by a Harvard College Research Program grant to Haiwen Chen as well as NIH grants to Ken Nakayama (EY01362), Margaret Livingstone (EY16187), and Richard Russell (EY017245).

References

- Bernstein IH, Lin TD, McClellan P. Cross- vs. within-racial judgments of attractiveness. Percept Psychophys. 1982;32:495–503. doi: 10.3758/bf03204202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstad P, Russell R. Beauty is in the we’of the beholder: Greater agreement on facial attractiveness among close relations. PERCEPTION-LONDON- 2007;36:1674. doi: 10.1068/p5793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PA, Maurer D. The influence of recent experience on perceptions of attractiveness. Perception. 2008;37:1216–26. doi: 10.1068/p5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Roberts AR, Barbee AP, Druen PB, Wu C. ‘Their ideas of beauty are, on the whole, the same as ours’: Consistency and variability in the cross-cultural perception of female physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:261–279. [Google Scholar]

- Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972;24:285–90. doi: 10.1037/h0033731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Good-looking people are not what we think. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:304–341. [Google Scholar]

- Geldart S, Maurer D, Carney K. Effects of eye size on adults’ aesthetic ratings of faces and 5-month-olds’ looking times. Perception. 1999;28:361–74. doi: 10.1068/p2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groesz LM, Levine MP, Murnen SK. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: a meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:1–16. doi: 10.1002/eat.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquet E, Rhodes G, Hayward W. Race-contingent aftereffects suggest distinct perceptual norms for different race faces. Visual Cognition. 2007;99999:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois J, Ritter J, Roggman L, Vaughn L. Facial diversity and infant preferences for attractive faces. Annual Progress in Child Psychiatry and Child Development 1992: Selection of the Years Outstanding Contributions. 1993;27 [Google Scholar]

- Langlois J, Roggman L. Attractive faces are only average. Psychological Science. 1990;1:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Kalakanis L, Rubenstein AJ, Larson A, Hallam M, Smoot M. Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:390–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DA, O’Toole AJ, Vetter T, Blanz V. Prototype-referenced shape encoding revealed by high-level aftereffects. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:89–94. doi: 10.1038/82947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DA, Rhodes G, Muller KM, Jeffery L. The dynamics of visual adaptation to faces. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272:897–904. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A, DeBruine L, Jones B, Waitt C. Category contingent aftereffects for faces of different races, ages and species. Cognition. 2008;106:1537–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffler G, Yourganov G, Wilkinson F, Wilson H. fMRI evidence for the neural representation of faces. Nature neuroscience. 2005;8:1386–1390. doi: 10.1038/nn1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. Racial ethnocentrism and judgment of beauty. The Journal of social psychology. 1964;63:59. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1964.9922213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller A, Swaddle J. Asymmetry, developmental stability, and evolution. Oxford University Press; USA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mori M. Bukimi no tani. Energy. 1970;7:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen Media Research. Report on Television. New York: New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Perrett D, May K, Yoshikawa S. Facial shape and judgements of female attractiveness. 1994 doi: 10.1038/368239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskin M, Newell FN. Familiarity breeds attraction: effects of exposure on the attractiveness of typical and distinctive faces. Perception. 2004;33:147–57. doi: 10.1068/p5028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reber R, Schwarz N, Winkielman P. Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;8:364–82. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G, Jeffery L, Clifford CW, Leopold DA. The timecourse of higher-level face aftereffects. Vision Res. 2007;47:2291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G, Jeffery L, Watson TL, Clifford CW, Nakayama K. Fitting the mind to the world: face adaptation and attractiveness aftereffects. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:558–66. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G, Jeffery L, Watson TL, Jaquet E, Winkler C, Clifford CW. Orientation-contingent face aftereffects and implications for face-coding mechanisms. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2119–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R. A sex difference in facial contrast and its exaggeration by cosmetics. Perception. doi: 10.1068/p6331. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels C, Butterworth G, Roberts T, Graupner L, Hole G. Facial aesthetics: babies prefer attractiveness to symmetry. PERCEPTION-LONDON- 1994;23:823–823. doi: 10.1068/p230823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater A, Von der Schulenburg C, Brown E, Badenoch M, Butterworth G, Parsons S, Samuels C. Newborn infants prefer attractive faces. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill R, Gangestad SW. Facial attractiveness. Trends Cogn Sci. 1999;3:452–460. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine T. A unified account of the effects of distinctiveness, inversion, and race in face recognition. Q J Exp Psychol A. 1991;43:161–204. doi: 10.1080/14640749108400966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Kaping D, Mizokami Y, Duhamel P. Adaptation to natural facial categories. Nature. 2004;428:557–61. doi: 10.1038/nature02420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Dayan P, Lipkin R, Qian N. Adaptation across the Cortical Hierarchy: Low-Level Curve Adaptation Affects High-Level Facial-Expression Judgments. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:3374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0182-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]