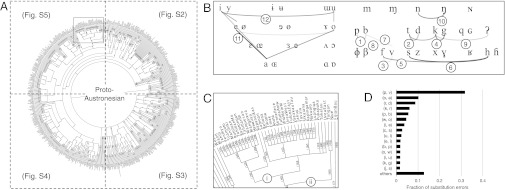

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the output of our system in more depth. (A) An Austronesian phylogenetic tree from ref. 29 used in our analyses. Each quadrant is available in a larger format in SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S5, along with a detailed table of sound changes (SI Appendix, Table S5). The numbers in parentheses attached to each branch correspond to rows in SI Appendix, Table S5. The colors and numbers in parentheses encode the most prominent sound change along each branch, as inferred automatically by our system in SI Appendix, Section 4. (B) The most supported sound changes across the phylogeny, with the width of links proportional to the support. Note that the standard organization of the IPA chart into columns and rows according to place, manner, height, and backness is only for visualization purposes: This information was not encoded in the model in this experiment, showing that the model can recover realistic cross-linguistic sound change trends. All of the arcs correspond to sound changes frequently used by historical linguists: sonorizations /p/ > /b/ (1) and /t/ > /d/ (2), voicing changes (3, 4), debuccalizations /f/ > /h/ (5) and /s/ > /h/ (6), spirantizations /b/ > /v/ (7) and /p/ > /f/ (8), changes of place of articulation (9, 10), and vowel changes in height (11) and backness (12) (1). Whereas this visualization depicts sound changes as undirected arcs, the sound changes are actually represented with directionality in our system. (C) Zooming in a portion of the Oceanic languages, where the Nuclear Polynesian family (i) and Polynesian family (ii) are visible. Several attested sound changes such as debuccalization to Maori and place of articulation change /t/ > /k/ to Hawaiian (30) are successfully localized by the system. (D) Most common substitution errors in the PAn reconstructions produced by our system. The first phoneme in each pair  represents the reference phoneme, followed by the incorrectly hypothesized one. Most of these errors could be plausible disagreements among human experts. For example, the most dominant error (p, v) could arise over a disagreement over the phonemic inventory of Proto-Austronesian, whereas vowels are common sources of disagreement.

represents the reference phoneme, followed by the incorrectly hypothesized one. Most of these errors could be plausible disagreements among human experts. For example, the most dominant error (p, v) could arise over a disagreement over the phonemic inventory of Proto-Austronesian, whereas vowels are common sources of disagreement.