Abstract

Background

African Americans bear an unequal burden of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer. The Deep South Network for Cancer Control (DSN) is a community–academic partnership operating in Alabama and Mississippi that was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to address cancer disparities using community-based participatory research approaches.

Objective

In addition to reporting on the plans of this work in progress, we describe the participatory process that local residents and the DSN used to identify needs and priorities, and elaborate on lessons learned from applying a participatory approach to the development of a community action plan.

Methods

We conducted 24 community discussion groups involving health care professionals, government officials, faith-based leaders, and other stakeholders to identify cancer health disparity needs, community resources/assets, and county priorities to eliminate cancer health disparities. To develop a community action plan, four working groups explored the themes that emerged from the discussion groups, taking into consideration evidence-based strategies and promising community practices.

Results

The DSN formulated a community action plan focusing on (1) increasing physical activity by implementing a campaign for individual-level focused activity; (2) increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables by implementing NCI’s Body and Soul Program in local churches; (3) increasing cancer screening by raising awareness through individual, system, and provider agents of change; and (4) training community partners to become effective advocates.

Conclusions

A community–academic partnership must involve trust, respect, and an appreciation of partners’ strengths and differences. The DSN applied these guiding principles and learned pivotal lessons.

Minorities in the United States experience higher cancer incidence and mortality rates than the rest of the population.1 African Americans continue to have poor chances of survival once cancer is diagnosed, suggesting disparities in access to and receipt of quality health care as well as in comorbid conditions.2 Breast cancer is the most common cancer among African-American women. Nationally, African-American women have a lower breast cancer incidence rate than white women, but higher mortality rates.3 For cervical cancer, African-American women have both higher incidence and mortality rates compared with white women.1,2 Colorectal cancer incidence rates are more than 20% higher and mortality rates about 45% higher in African Americans than in whites.2 From a state perspective, similar cancer mortality disparities are noted for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers.4,5

To combat national- and state-level cancer health disparities, the NCI launched the Community Networks Program (CNP) in 2005 to better understand why minorities and the poor have higher cancer rates than others, and to eliminate disparities by involving local communities in education, research, and training. A total of 25 institutions nationwide participated in the CNP.6 The DSN, a community–academic partnership operating in Alabama and Mississippi, was one of the funded CNPs.

Building on a 5-year track record of success,7–12 the DSN was well-poised to meet the goals of the CNP, having already (1) established trust with grassroots partners in underserved areas of Alabama and Mississippi, (2) developed and maintained robust coalitions, and (3) trained hundreds of community volunteers as research partners. Although the first 5 years of DSN produced promising outcomes,7–12 there were shortcomings. First, the specific aims and outcomes were defined a priori. Second, DSN activities were focused on the individual and interpersonal levels of change, with a lesser focus on the relationship between the individual and the environment. As a result, factors such as economics, social policies, and politics (social determinants of health) were not fully examined.

The CNP funding provided an opportunity for DSN to involve the community in the identification of needs and assets regarding cancer health disparities. By linking the wisdom and first-hand knowledge of persons affected by a health problem with conventional research,13–18 the DSN and community members were able to develop realistic priorities and viable solutions for the community.

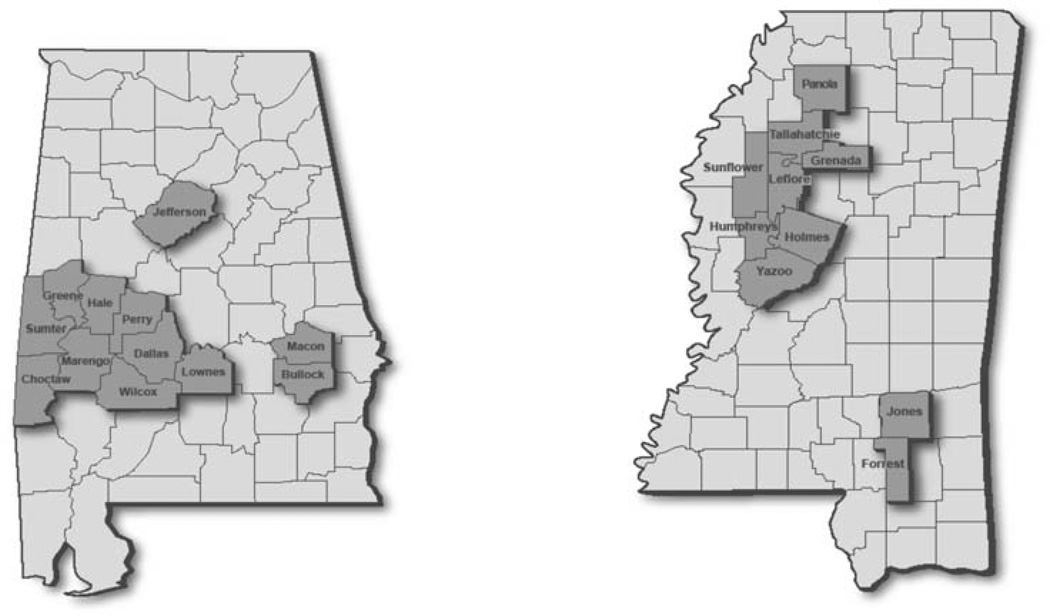

Because of a history of distrust by some African Americans in the health care system and health research,19–22 this inclusive approach was vital to maintaining trust between DSN and community residents. The concepts of inclusiveness and trust were particularly important to the DSN because we were committed to working in not only underserved, but economically challenged urban and rural areas of Alabama and Mississippi. The socioeconomic challenges are especially pronounced in the Alabama Black Belt and the Mississippi Delta (Figure 1), rural regions targeted by the DSN.

Figure 1.

Alabama and Mississippi Maps Highlighting DSN Rural and Urban Counties

The Alabama Black Belt, an area named for its dark soil, is also known for having high poverty rates among African Americans. Although Alabama’s population is 26% African Americans, more than 60% of African Americans live in the Black Belt and 37% of families with children under age 18 years live in poverty.23,24 Additionally, the area has declining populations, soaring unemployment, poor access to education and medical care, substandard housing, and high rates of crime.25 The Mississippi Delta is located in the northwest section of the state. Technically not a delta, but part of an alluvial plain,26 this rural area has been referred to as the “third-world country in the heart of America.”27 The Delta struggles with the challenges of chronic disease and barriers to accessing health care.28 As a result, residents experience higher rates of cancer, heart disease, and infant mortality.29

In this article, we have presented the DSN as an example of a partnership that seeks to eliminate health disparities in breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers by applying community-based participatory research principles to the process of needs assessment and community action plan development with local residents from 22 Alabama and Mississippi counties. First, we describe the participatory process that local residents and the DSN engaged in to determine needs and identify solutions. Second, we describe the community action plan that resulted from this collaborative endeavor. Finally, we share the lessons learned from applying community-based participatory principles to the issue.

METHODS

In November 2005, the DSN partnership began discussions regarding the purpose and scope of needs assessment activities, and data collection strategies appropriate for use in underserved counties. Through monthly meetings and calls, DSN members recommended that the needs assessment process: (1) Include the opinions of various community stakeholders, (2) focus on community assets and resources, and (3) disseminate all findings to the community for feedback.

After a 3-month iterative process, a consensus was reached to use a community discussion group methodology.30 Discussion groups are growing in popularity as a viable method to engage hard-to-reach segments of the population in research. The discussion group topic guide contained questions that explored (1) cancer health disparity needs, (2) community resources/assets, and (3) county priorities to eliminate cancer health disparities.

In March 2006, DSN community partners started recruiting a convenience sample of 8 to 10 community members aged 20 and older to participate in one county discussion group. Given that this was a convenience sample, community partners relied on their social circles as their main recruitment strategy. While these efforts were underway, the other DSN partners developed informed consent documents, which were administered at the beginning of each session, and secured meeting locations, refreshments, and participant incentives.

Each session was tape recorded and transcribed. Then two evaluators independently read the original transcript and identified themes. The data were then summarized within and across groups and shared with the DSN community–academic partnership for review and discussion.

Next, a series of meetings and calls were scheduled between the DSN partners and discussion group participants to review the data and to begin outlining a community action plan. From these discussions, a draft community action plan was developed. Discussion group and DSN participants then divided into four working groups composed of eight individuals to finalize components of the community action plan. In a 3-month period, working groups were responsible for (1) conducting a literature review to identify interventions based on themes, (2) examining an inventory of programs targeting African Americans and focused on breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers, (3) reviewing the successes and lessons learned from previous DSN activities, and (4) keeping their respective constituents and peers apprised of DSN updates.

RESULTS

Needs Assessment Results

A total of 24 discussion groups, involving 224 participants (90% African Americans, 10% white; 84% women, and 16% men) were conducted with a convenience sample of health care professionals (21%), government officials (16%), faith-based leaders (26%), and other stakeholders across Alabama and Mississippi. More than half of the participants were married and employed full time. Their average age was 51 years and 41% had graduated from a 4-year college or university.

The discussion group data revealed similarities and differences across state and county lines. The question that produced the most variability involved the identification of cancer resources/assets available to local residents. Because of the open-ended nature of this question, the responses were numerous. However, in Alabama, a frequently cited resource/asset was the REACH 2010 project,31 funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that worked in concert with DSN to eliminate cancer health disparities. This particular resource/asset was not available in Mississippi. It was impressive to hear the community identify different types of resources/assets available in underserved communities.

Overall, the discussion group findings revealed several consistent themes across both states. Most participants considered breast cancer as the top cancer disparity that they felt comfortable addressing. The other top cancer disparities were colorectal, prostate, cervical, and lung. Hypertension, heart disease, obesity, and diabetes were also identified as top disparities. Participants documented eight of the Healthy People 201032 leading health indicators as problems in their communities, which included physical activity, overweight and obesity, tobacco use/smoking, substance abuse, risky sexual behavior, mental health/stress, environmental quality, and access to health care.

Participants were concerned about environmental contamination in their communities and the lack of governmental concern. They reported that cancer myths were still barriers to getting screened and felt more needed to be done to promote lifestyle changes, especially around diet, physical activity, and smoking. Yet, they indicated that lifestyle changes were not enough if they live in contaminated environments.

Additionally, participants framed their perceptions of cancer health disparities and identified opportunities for interventions based on three levels of influence: Individual, provider, and system levels. See Table 1 for selected discussion group quotes based on these levels. Given participants’ ecological approach to eliminating cancer health disparities, working groups were formed to develop a multilevel community action plan based on these themes and levels of influence.

Table 1.

“Quotable Quotes” From Discussion Group Participants

| Individual Level | |

| “People need to have the ability to ask for what they need and what they want.” | |

| “Basically just changing your lifestyle, how you eat … stress … and even if you live in a community where there is environmental pollution, you have to take a stance and look at yourself, and then on top of that, don’t be afraid.” | |

| Provider Level | |

| “Our local doctors, since we’ve gotten the machine to do mammograms, have been more active in getting breast screenings done here.” | |

| “Even with the medical profession and resources in the community. I think that trust is something that‘s very important in the African-American communities. That’s something that has to be built upon.” | |

| Systems Level | |

| “We got a Healthy City Campaign here with a proclamation from the mayor, and we have a campaign going on and we are encouraging people to get out and walk.… We’re trying to get the restaurants involved … any restaurant you go to in the city … you will find some fried food … we’re asking them to cooperate with us, and I’ve been getting some response back.” | |

| “Talk is cheap. I think that action needs to be taken. I’m talking at the school level. I remember, you know back in high school, there was a real health class. They would talk to you about that.” |

Community Action Plan Development

Approximately 32 DSN community–academic partners and discussion group participants agreed to join one of the four working groups. Each working group was responsible for (1) conducting a literature review to identify suitable interventions based on identified themes, (2) examining an inventory of programs targeting African Americans and focused on breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers, (3) reviewing the successes and lessons learned from previous DSN activities, and (4) keeping their respective constituents and peers apprised of DSN updates. Although there was no prescribed method for completing the four tasks, working groups identified helpful websites and resources their members could refer to for assistance.

Each working group decided to elect a chair and co-chair from within their membership. The chair and co-chair were responsible for overseeing the completion of assignments, scheduling working group meetings and calls, and maintaining the group’s momentum. Some working groups even chose to pair academicians and local community residents to promote a co-learning and empowering experience. Some members volunteered to assist with certain assignments based on their capacity levels and time constraints.

After months of data-driven deliberations, working group members narrowed their community action plan priority lists and decided to focus on increasing and/or promoting participation in (a) physical activity, (b) breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening, (c) advocacy efforts, and (d) healthy eating. Once these areas were approved by all working groups, the next step was to identify evidence-based strategies and/or local promising community strategies. The community action plan was finalized in January 2007 and included the following four components: (1) Increasing physical activity by implementing a promising practice derived from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Minority Health and Research Center’s WALK campaign33 (individual-level focused activity); (2) increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables by implementing NCI’s Body and Soul34 in local churches (individual- and system-level focused activities); (3) increasing cancer screening through cancer awareness activities that targeted the individual, system and providers as agents of change (provider/agent of change level focused); and (4) training DSN community partners to become effective advocates using the Midwest Academy’s Direct Action Organizing35 techniques (individual- and system-level focused activities). Although not shown here, the community action plan also included a step-by-step protocol that outlined the roles and responsibilities of the DSN community–academic partners, along with process, impact, and outcome evaluation measures.36

DISCUSSION

In this article, the DSN community–academic partnership was presented as an example of a partnership that seeks to eliminate health disparities in breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers by applying community-based participatory research principles to the process of needs assessment and community action plan development. Throughout this collaborative process, both the DSN and the community learned valuable lessons that will be remembered and applied as we continue working together.

Lesson 1

If the problem is in the community; the solution is in the community. As a direct result of asking community members to share their thoughts in a discussion group, we were able to co-develop a multilevel community action plan that included evidence-based strategies and local promising practices. Because this entire collaborative process was based on a participatory approach, our specific aims and strategies were not defined a priori. However, we, along with the project sponsor, were pleased that the community desired to address environmental issues through advocacy efforts and focus their attention on increasing physical activity levels, cancer screenings, and the consumption of fruits and vegetables. As co-developers of the community action plan, the community is likely to own the final product and sustain it as well.

Lesson 2

Resources are in the eye of the beholder. By conducting informal discussion groups with various community members, we learned that underserved communities wanted to have a balanced discussion regarding their assets and their needs. When given the chance to talk about their assets, the responses varied across county and state lines and were numerous. Many of the assets mentioned were not the typical institutional resources (e.g., banks, community foundations), but the individuals who had access to and/or connections with various social, economic, and/or health systems. Therefore, despite being labeled as “underserved” communities, many of the local residents felt empowered by their ability to leverage connections within their interpersonal, social, and community circles.

Lesson 3

Time is like money; use it wisely. It is no secret that community-based participatory research takes time. Therefore, we dedicated several months to engaging in purposeful brainstorming with community partners. Having designated planning time enabled us to adjust our project schedule to complete all assessment and community action plan activities. More important, we asked community and academic partners in advance to identify factors that would keep them engaged in this collaborative endeavor despite competing demands for their time and attention. Using their responses, we were able to maintain working group momentum during the community action plan development process.

Despite the successes of this collaborative partnership, we also faced challenges during the first year. Although we were able to conduct 24 discussion groups across two states, we recruited participants from conveniently accessible groups. We acknowledge that using a more rigorous data collection method would have allowed our results to be generalized to the public; however, we verified the accuracy of our findings by triangulating the data we collected to (1) needs assessment data derived from our previous DSN activities,7–12 (2) formative evaluations conducted in Alabama by the CDC-funded REACH 2010 project,37 and (3) community mobilization assessments conducted in Mississippi.38

CONCLUSION

The DSN community–academic partnership serves as an example for community stakeholders and researchers who are interested in using participatory approaches to eliminate cancer health disparities. By incorporating community-based participatory principles13–15 into our planning, formative evaluation, and community action plan development phases, the DSN partnership was willing to trust the participatory research process and adjust to paradigm shifts to ensure that we worked in a collaborative and equitable fashion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank every organization and individual involved in and affiliated with the DSN community-academic partnership. Without your support, the accomplishments outlined in this paper would not be possible. Special recognitions are extended to: community health advisors trained as research partners, community network partners, local, private, state and national partners, project administrators, coordinators, managers, and director, support staff, investigators, and the NCI program officer.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA U01CA114619). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI, NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans, 2009–2010. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, Ries LA, Wu X, Jamison PM, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans, 2007–2008. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Alabama cancer facts and figures, 2008. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Control P.L.A.N.E.T. Available from: http://cancercontrolplanet.cancer.gov.

- 6.National Cancer Institute. [cited 2009 Sep 2];Community networks program information. Available from: http://crchd.cancer.gov/cnp/program-information.html.

- 7.Lisovicz N, Johnson RE, Higginbotham J, Downey JA, Hardy CM, Fouad MN, et al. The Deep South Network for cancer control. Building a community infrastructure to reduce cancer health disparities. Cancer. 2006;107(8 Suppl):1971–1979. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge EE, Fouad MN, Hinton AW, Hardy CM, Liscovicz N, White-Johnson F, et al. The Deep South network for cancer control: Eliminating cancer disparities through community-academic collaboration. Fam Community Health. 2005;28:6–19. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lisovicz N, Wynn T, Fouad M, Partridge EE. Cancer health disparities: what we have done. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:254–259. doi: 10.1097/maj.0b013e31816a43ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy CM, Wynn TA, Huckaby F, Lisovicz N, White-Johnson F. African American community health advisors trained as research partners: Recruitment and training. Fam Community Health. 2005;28:28–40. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinton A, Downey J, Lisovicz N, Mayfield-Johnson S, White-Johnson F. The community health advisor program and the deep South network for cancer control: Health promotion programs for volunteer community health advisors. Fam Community Health. 2005;28:20–27. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson RE, Green BL, Anderson-Lewis C, Wynn TA. Community health advisors as research partners: an evaluation of the training and activities. Fam Community Health. 2005;28:41–50. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community-based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly JG, Mock LO, Tandon DS. Collaborative inquiry with African-American community leaders: Comments on a participatory action research process. In: Reason P, Bradbury H, editors. Handbook of action research. London: Sage; 2001. pp. 348–355. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green LW, George MA, Daniel M, Frankish CJ, Herbert CP, Bowie WR, et al. Study of participatory research in health promotion. Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallerstein N. Power between evaluator and community: Research relationships within New Mexico’s healthier communities. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macaulay AC, Nutting PA. Moving the frontiers forward: Incorporating community-based participatory research into practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2006:4–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In: Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of community psychology. New York: Plenum; 2000. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan WC, Vaughn AC, Hood RG. African Americans and HIV/AIDS; cultural concerns. Aids Read. 2004;14:S22–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas JC, Eng E, Earp JA, Ellis H. Trust and collaboration in the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. Public Health Rep. 2001;11:540–547. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson SB, Ashley M, Haynes MA. Attitude of African Americans regarding prostate cancer clinical trials. J Community Health. 1996;21:77–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01682300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St. George DMM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Census Bureau. [cited 2009 Sep 2]; Available from: http://www.census.gov.

- 24. [cited 2009 Aug 31];Overview of Black Belt Action Commission, commission charge, polling, statistics and members. Available from: http://blackbeltaction.alabama.gov/Docs/BBAC_Overview.pdf.

- 25.Black Belt Fact Book. [cited 2010 Sep 3];University of Alabama Institute for Rural Health Research. Available from: http://irhr.ua.edu/blackbelt/intro.html.

- 26.Mississippi Delta. [cited 2010 Sep 3]; Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mississippi_Delta.

- 27.Parfit M. And what words shall describe the Mississippi, great father of rivers. Smithsonian. 1993 Feb;:36. [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Agriculture. Economic research service. [cited 2009 Aug 20]; Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/AboutERS/

- 29. [cited 2009 Ag 15];Health and economics in the Mississippi Delta: Problems, opportunities. Available from: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1YLZ/is_1_31/ai_n27893244/ [PubMed]

- 30. [cited 2010 Sep 3];Talking circles. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talking_circle.

- 31.Ma’at I, Fouad M, Grigg-Saito D, Liang S, McLaren K, Pichert J, et al. REACH 2010: A unique opportunity to create strategies to eliminate health disparities among women of color [Special issue: The health of women of color] Am J Health Studies. 2001;17:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [cited 2009 Jan 18];About healthy people 2010. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/

- 33.University of Alabama at Birmingham. [cited 2010 Sep 3];Minority Health & Health Disparities Research Center. Available from: http://mhrc.dopm.uab.edu/default.html.

- 34.Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, Periasamy S, et al. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bobo K, Kendall J, Max S. Organizing for social change in the 90’s. Santa Ana (CA): Seven Locks Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scarinci IC, Johnson RE, Hardy C, Marron J, Partridge EE. Planning and implementation of a participatory evaluation strategy: A viable approach in the evaluation of community-based participatory programs addressing cancer disparities. Eval Program Plann. 2009;32:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fouad MN, Nagy MC, Johnson RE, Wynn TA, Partridge EE, Dignan M. The development of a community action plan to reduce breast and cervical cancer disparities between African-American and white women. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(Suppl 1)(3):S53–S60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Center for Sustainable Health Outreach. [cited 2010 Sep 3]; Available from: http://www.usm.edu/csho/