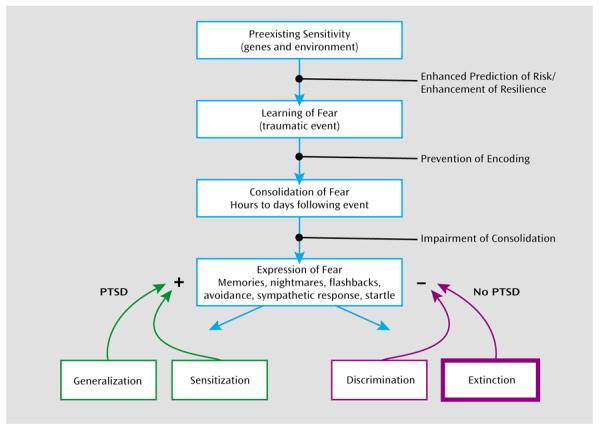

FIGURE 4. The Developmental Progression of PTSD.

aThe strength and regulation of fearful memories is affected by numerous factors both before and after the traumatic or fearful event occurs. Genetic heritability comprises up to ~40% of the risk for both depression and PTSD, and early childhood abuse is a strong risk factor for all mood and anxiety disorders. Further understanding of the roles of genes and environment may allow enhanced prediction of risk and enhancement of resilience in vulnerable populations. Memories are not permanent at the time of the trauma, and psychological and pharmacological approaches to prevent the initial encoding of the trauma are under study. Memories then undergo a period of consolidation in which they shift from a labile state to a more permanent state. Impairing the consolidation (or even reconsolidation) would be an alternative way to prevent the sequelae of long-term trauma memories. The expression of traumatic memories, which can be the source of symptoms in fear-related disorders, is diminished by the process of extinction when repeated therapeutic exposures to the fear-related cues reduce or inhibit the fear memories over time. In contrast, there is some evidence that in individuals who develop PTSD and other pathology, a combination of avoidance of sufficient exposure with intrusive and uncontrollable memories leads to sensitization of the fear response. Enhancing discrimination and extinction of fear memories is a key aspect of recovery in the psychotherapeutic approaches to treating PTSD.