Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Castleman's disease (CD) is a rare disease with unknown etiology and is clinically associated with lymph nodes enlargement. Primary axillary localization of CD represents 2% of the cases. CD rarely occurs in the breasts.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We herein describe a rare case of CD that initially presented in the breast intramammary lymph node and demonstrated axillary adenopathy. Pathologic analysis showed the hyaline vascular form. The patient underwent axillary lymphadenectomy. The natural history was irregular because the localized CD progressed to a systemic form of CD. At 4.6 years of follow-up a Hodgkin's lymphoma appeared.

DISCUSSION

This is the fourth published case of localized breast CD published. It is important to evaluate other clinical lymphadenopathies at the time of diagnosis, and computed tomography is important for disease evaluation and follow-up.

CONCLUSION

Patients must undergo axillary lymphadenectomy when showing clinical symptoms. Irregular progression prompts new lymph node biopsy because of the potential presence of associated diseases.

Keywords: Breast imaging, Castleman's disease, Intramammary lymph node, Axillary lymph nodes, Hodgkin's lymphoma, Breast neoplasia

1. Introduction

Castleman's disease (CD) is a rare disease with unknown etiology and is clinically associated with lymph node enlargement.1,2 Localized breast CD is extremely rare. It is clinically related to intramammary lymph node (ILN) disease or interpectoral lymph node with axillary adenopathy. Pathologic analysis of localized CD frequently shows the hyaline vascular form.3–6

CD may progress to a systemic form, the radiological aspects of which frequently comprise a local mass and regional or multiple adenopathy. The disease evolves aggressively, usually progressing to death, secondary to infection or a second neoplasia, resistant to corticosteroids and chemotherapy.2

Radiographic signs of CD are not specific and are frequently related to a mass or adenopathy. Because of the absence of specific symptoms or signs and the potential for development into the systemic form, computed tomography (CT) is important for clinical evaluation, treatment planning, and follow-up.7 Irregular progression must undergo pathological confirmation because of the potential presence of associated diseases. We herein present the fourth published case of localized breast CD. This report illustrates a case of breast localized CD that progressed to a systemic form and subsequent Hodgkin's lymphoma.

2. Presentation of case

A 49-year-old female patient presented with a 2-year history of a right-sided axillary lymph node growth. On examination, axillary adenopathy and breast nodulation were noted. Mammography showed only slight bulging with a soft-tissue density in the right axillary region next to the pectoralis major muscle (which coincided with the clinical complaint). Ultrasound revealed well-defined rounded, solid nodules in the right axilla with a hyper-flux pattern on Doppler examination, which was compatible with increased lymph node size, although nonspecific (Fig. 1). Resection of the breast lymph node showed angiofollicular hyperplasia, also known as giant lymphoid hyperplasia or CD of the hyaline-vascular form (CD/HVF) (Fig. 3). Hypergammaglobulinemia was not observed, and an HIV serological test was negative. Thoracic and abdominal CT showed absence of other lymphadenopathy. The patient underwent axillary dissection, which confirmed the diagnosis of CD/HVF.

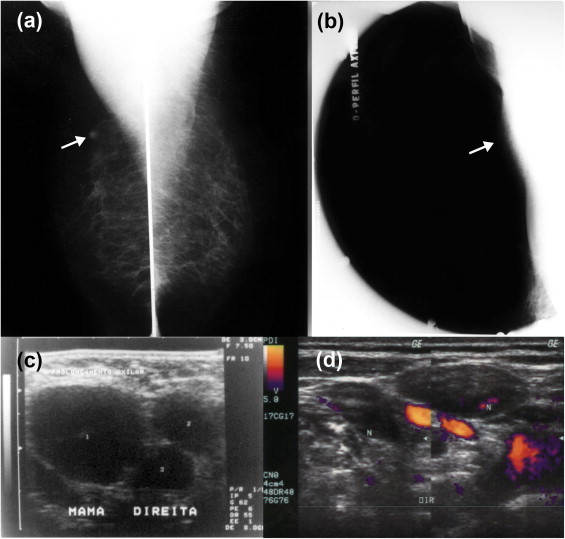

Fig. 1.

Mammographic and ultrasonographic findings. (a) Mammography, mediolateral oblique view. The arrow shows asymmetry related to intramammary lymph nodes; (b) mammography. Spot located in the axilla. The arrow shows a bulge over the pectoral muscle. (c) Ultrasound using a high frequency linear probe. Right axillary lymphadenopathy is seen, characterized by at least three well-defined, rounded, hypoechogenic solid nodules with loss of the usual adipose hilum (increased lymph node size) and (d) Color Doppler. Central and peripheral hyperflux can be seen.

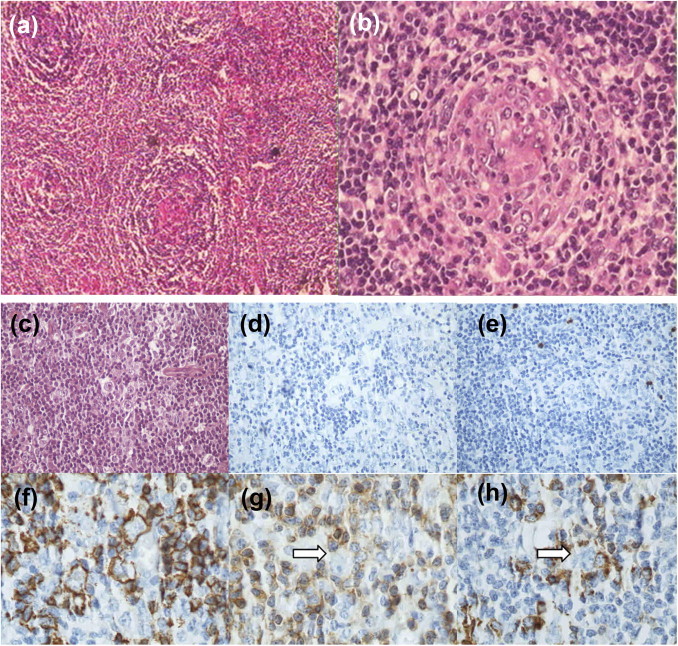

Fig. 3.

Pathologic findings. (a) Histology of the hyaline-vascular form. HE, 40×: lymph node with lymphoid cells in an “onion skin” pattern with a hyaline center. (b) HE, 200×. (c) Hodgkin's lymphoma. HE, 400×. (d) Negativity for CD30. (e) Negativity for CD15. (f) Atypical cells immunoexpressing CD20. (g) Arrow shows neoplastic cells surrounded by CD3+ T cells and (h) Arrow shows neoplastic cells surrounded by CD57+ T cells.

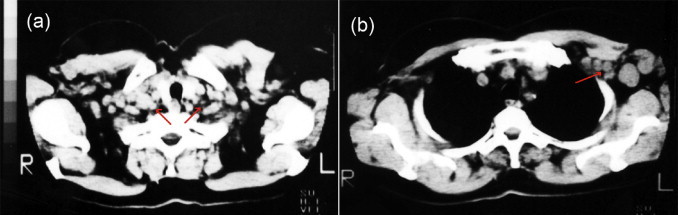

Three months later, supraclavicular adenopathy appeared. Eight monthly cycles of prednisone were then administered, and the patient remained asymptomatic for 18 months. Because of the reappearance of the supraclavicular disease and left axillary symptomatic disease, the patient was submitted to CT with contrast. This confirmed the presence of increased numbers of multiple small, high-uptake mediastinal lymph nodes in the paratracheal and pretracheal regions and left axilla (Fig. 2). The patient then underwent left axillary lymphadenectomy; pathologic examination showed CD/HVF, and prednisone was reintroduced, which helped to stabilize the patient's condition.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography findings at 18 months after diagnosis. (a) Axial slices of the supra-aortic mediastinal region and (b) Prevascular space. The arrow shows slightly increased and moderately increased paratracheal and pretracheal lymph nodes in the left axillary region.

After 4.6 years of follow-up, lymph nodes reappeared in the right supraclavicular fossa. A biopsy taken from this region showed the presence of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma (Fig. 3). The patient underwent adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD) chemotherapy and mini-mantle radiotherapy with a boost in the fossa and in the cervical region. A favorable result was obtained. Currently, 12.9 years after the onset of this condition, the patient is alive and disease-free.

3. Discussion

CD or angiofollicular giant lymph node hyperplasia is a rare, benign condition that was first described in 1956 in patients with single mediastinal lymph node adenopathy.1,2 This was later related to lymph node involvement in multiple groups.1,2 CD originates in the lymphoid tissue. The etiology and pathogenesis are unknown but an immunoregulatory abnormality is implicated in its development.2,3 Differential diagnoses may include lymphoid neoplasms, inflammatory reactions and metastatic disease.3,8 Primary axillary localization of CD represents 2% of the cases3,8,9 and CD is rare in the breasts.3–6,10

CD is clinically divided into localized or systemic forms and histologically into the hyaline-vascular, plasmacytic subtypes or mixed subtypes.1,2,11 Although extremely rare, the appearance of localized CD in the breast is related to interpectoral lymph nodes4 or ILNs with frequent involvement of axillary nodes5 or lymphoid tissue in the subcutaneous mammary tissue.4–6 To the best of our knowledge, it is the fourth published case4–6 of localized CD form in the breast.

By definition, ILNs are surrounded by breast tissue.12 They are clinically and mammographically occult in 37% of patients and appear as a solid hypoechoic mass of indeterminate etiology in 12%.13 Discovered as a nonpathological lump on mammography, frequently in the upper-outer quadrant, their detection does not require further diagnostic investigation, unless enlargement of the mass is seen on a subsequent mammographic examination. A size of less than 10 mm14 or 15 mm15 was initially considered to be normal, but their density, replacement of central fat, and shaggy margins are more important signs to investigate.14 On sonographic examination, when the echogenic hilum is absent, a metastatic ILN displays a completely hypoechoic echotexture.12,13 Associated with a round shape and well-delineated margins, it may mimic a benign mass and resemble a synchronous benign-appearing breast nodule in a patient with breast cancer.12 If the findings are suspicious the lymph node should be biopsied.13 The main differential diagnoses are inflammation, reaction to dermatitis, tuberculosis, lymphoproliferative disease, and breast cancer.15 Chang et al. published a case report of a ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion associated with a synchronous CD in the axilla, mimicking axillary metastasis.10

In the present case, CD was present in a breast ILN in the mammary tail of Spence with axillary adenopathy. ILN and axillary CD disease should therefore be included as a differential diagnosis of axillary adenopathy. Radiographic signs of CD are nonspecific and are frequently related to a mass or adenopathy. Mammography can show any lesion,4 a nodular area with irregular margins without microcalcifications,5 or just axillary adenopathy (Fig. 1). Ultrasound shows a hypoechoic mass5 with hyperechoic regions16 or lymphadenopathy.5,10 Color Doppler sonography shows an artery penetrating the hilum of the mass and fine accessory peripheral arteries,16 an unclear lymph-like morphology with an irregular vascular pattern,5 or loss of the usual adipose hilum (Fig. 1).

The localized form of CD is generally asymptomatic, with clinical manifestations secondary to the tumor growth. The hyaline-vascular form is the most frequently observed type of localized CD. It occurs in 76–91% of patients with localized disease, and the differential diagnoses include adenopathies of other origins.11 The sites involved are overwhelmingly nodal, and the mediastinum and cervical regions accounting for 73% of the cases.2 The treatment for the localized disease comprises of complete resection of the lesion, which results in improvement of the symptoms and a cure in most cases.2,17 For localized and unresectable disease, radiotherapy and corticoids can be used.1,2,17

In such cases, local resection allows for initial control of the CD, as described in our patient,5 but the disease progresses to a systemic form with the appearance of lymphadenopathy at multiple sites. On CT, the disease appears as a homogeneous16 or heterogeneous soft-tissue-attenuating masses, that can be associated with lymphadenopathy18 or just a lymphadenopathy (Fig. 3). Enhancement after the intravenous administration of contrast material is frequent.18 The CT is important for treatment planning and follow up.7

The systemic form is frequently associated with plasmocitary histological findings and systemic symptoms. Clinically characterized by multiple adenopathies resistant to corticosteroids and chemotherapy. The disease evolves aggressively, usually resulting in death secondary to infection or a second neoplasia.2,11 There are associations with second primary tumors such as lymphoma and sarcoma.11 There is no specific treatment; patients are treated with corticosteroids, chemotherapy, and interferon, and the results are unpredictable.17 The present case was treated with corticosteroids and chemotherapy with partial control of the CD.

The unfavorable clinical progression with increased severity of lymphadenopathy led to a subsequent diagnosis of Hodgkin's lymphoma, which is an extremely rare condition.19 The clinical progression prompted us to perform a new histological evaluation, and the patient's disease was controlled. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma may occur in 18% of patients with systemic CD,20 while Hodgkin's lymphoma occurs less frequently17 and has been associated with the multicentric plasma-cell variant of CD.19

Patients must be followed up carefully because of the potential for irregular progression. CD is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The cause of death is usually directly related to the disorder itself, infectious complications, or a second primary neoplasia.2

4. Conclusion

Breast CD disease is a rare disease, and when it occurs in the breast, it appears in the ILN. It is important to evaluate other clinical lymphadenopathies at the time of diagnosis and CT is important for diagnosis and follow-up. Patients with clinically symptomatic disease must undergo lymphadenectomy. Irregular progression should be assessed with new lymph node biopsies because of the potential for Hodgkin's lymphoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, which can have the same clinical appearance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this Journal on request.

Author's contribution

R.A.C. Vieira contributed in patient surgery, collect the data and organiz the article. J.S. Kunizaki contributed in review the case data. A.L. Canto involved in patient pathologist. A.D.B. Mendes contributed in patient chemotherapy treatment and follow up. J.S. Vial involved in patient diagnosis and follow up. A.G. Zucca-Matthes revised the article improving the versions. A.U. Watanabe revised the radiological aspects of the article. C. Scapulatempo Neto revised the pathological aspects of the article.

References

- 1.Bowne W.B., Lewis J.J., Filippa D.A., Niesvizky R., Brooks A.D., Burt M.E. The management of unicentric and multicentric Castleman's disease: a report of 16 cases and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1999;85(3):706–717. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990201)85:3<706::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarty M.J., Vukelja S.J., Banks P.M., Weiss R.B. Angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman's disease) Cancer Treatment Reviews. 1995;21(4):291–310. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(95)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elizalde J.M., Eizaguirre B., Lopez J.I. Angiofollicular giant lymph node hyperplasia that presented with an axillary mass. European Journal of Surgery. 1993;159(3):183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Silva B.B., Lopes-Costa P.V., Melo P.M., Pires C.G. Castleman's disease in interpectoral lymph node mimicking mammary gland neoplasia. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2008;54(1):63–64. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.39206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fama F., Berry M.G., Linard C., Patti R., Ieni A., Gioffre-Florio M. Multicentric Castleman disease: an unusual breast lump. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(28):e126–e127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malaguarnera M., Restuccia N., Laurino A., Lo Manto P.C., Vinci E., Pistone G. Extralymphonodal Castleman's dis-esase. A case-report. Panminerva Medica. 1999;41(4):363–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caterino M., Giglio L., Finocchi V., Crecco M. Current role of computerized tomography in the diagnosis and follow-up of Castleman's disease. Evaluating 2 mixed-variety cases. Radiology Medicine. 2000;100(6):513–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paraskevaides E.C., Wilson M.C. Massive axillary lymph-node hyperplasia in pregnancy: a case report. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 1988;29(4):353–355. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(88)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selva G., Imbriaco M., Riccardi A., Sparano L., Sodano A. Angiofollicular lymphoid hyperplasia (Castleman disease) of axillary localization. A case. Radiology Medicine. 2000;100(4):290–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang Y.W., Noh H.J., Hong S.S., Hwang J.H., Lee D.W., Moon J.H. Castleman's disease of the axilla mimicking metastasis. Clinical Imaging. 2007;31(6):425–427. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrada J., Cabanillas F., Rice L., Manning J., Pugh W. The clinical behavior of localized and multicentric Castleman disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1998;128(8):657–662. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solorzano S., Seidler M., Mesurolle B. Metastatic intramammary lymph node as a synchronous benign-appearing breast nodule detected in a patient with breast cancer. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2009;192(6):W349. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edeiken-Monroe B.S., Monroe D.P., Monroe B.J., Arnljot K., Giaccomazza M., Sneige N. Metastases to intramammary lymph nodes in patients with breast cancer: sonographic findings. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 2008;36(5):279–285. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dershaw D.D. Isolated enlargement of intramammary lymph nodes. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1996;166(6):1491. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.6.8633471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jellici E., Minniti S., Malago R., Fanto C., Pozzi Mucelli R. Focal breast lesions with benign appearances. Review of eight breast cancers with initial features of intramammary lymph node. Radiology Medicine. 2006;111(8):1078–1086. doi: 10.1007/s11547-006-0106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bui-Mansfield L.T., Chew F.S., Myers C.P. Angiofollicular lymphoid hyperplasia (Castleman disease) of the axilla. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2000;174(4):1060. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.4.1741060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dispenzieri A., Gertz M.A. Treatment of Castleman's disease. Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 2005;6(3):255–266. doi: 10.1007/s11864-005-0008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAdams H.P., Rosado-de-Christenson M., Fishback N.F., Templeton P.A. Castleman disease of the thorax: radiologic features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1998;209(1):221–228. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.1.9769835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unsal Tuna E.E., Ozbek C., Arda N., Ilkdogan E., Dere H., Ozdem C. Development of a Hodgkin disease tumor in the neck of a patient who previously had undergone complete excision of a hyaline-vascular Castleman disease neck mass. Ear, Nose, and Throat Journal. 2010;89(4):E20–E23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dham A., Peterson B.A. Castleman disease. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2007;14(4):354–359. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328186ffab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]