Abstract

We examined the relationship between three discrimination skills (visual, visual matching-to-sample, and auditory-visual) and four stimulus modalities (object, picture, spoken, and video) in assessing preferences of leisure activities for 7 adults with developmental disabilities. Three discrimination skills were measured using the Assessment of Basic Learning Abilities Test. Three participants mastered a visual discrimination task, but not visual matching-to-sample and auditory-visual discriminations; two participants mastered visual and visual matching-to-sample discriminations, but not auditory-visual discrimination, and two participants showed all three discriminations. The most and least preferred activities, identified through paired-stimulus preference assessment using objects, were presented to each participant in each of the four modalities using a reversal design. The results showed that (1) participants with visual discrimination alone showed a preference for their preferred activities in the object modality only; (2) those with visual and visual matching-to-sample discriminations, but not auditory-visual discrimination, showed a preference for their preferred activities in the object but not in the spoken modality, and mixed results in the pictorial and video modalities; and (3) those with all three discriminations showed a preference for their preferred activities in all four modalities. These results provide partial replications of previous findings on the relationship between discriminations and object, pictorial, and spoken modalities, and extend previous research to include video stimuli.

Preference assessments are important tools for educators and caregivers who work with individuals with developmental disabilities. Educators and caregivers can use preference assessments to identify reinforcers that can be used to strengthen adaptive skills of individuals with developmental disabilities during training programs (Green et al., 1988; Logan et al., 2001; Pace, Ivancic, Edwards, Iwata, & Page, 1985). Furthermore, allowing individuals with developmental disabilities to make choices contributes to their quality of life (Hughes, Hwang, Kim, Eisenman, & Killian, 1995; Stock, Davies, Secor, & Wehmeyer, 2003).

Preference assessment effectiveness (i.e., their ability to distinguish high preference items from less preferred items) depends both on the presentation modality of the items or activities used, and on the discrimination skills of the individuals whose preferences are assessed. Conyers et al. (2002), for example, measured visual, visual matching-to-sample, and auditory-visual discrimination skills of nine persons with mental retardation using the Assessment of Basic Learning Abilities (ABLA) Test (Kerr, Meyerson, & Flora, 1977; Martin & Yu, 2000). In their first experiment with food items, they found that (a) all three participants who passed the visual discrimination assessment, but failed both the visual matching-to-sample and the auditory-visual discrimination assessments on the ABLA test could consistently select their most preferred item in object preference assessment but not in picture or verbal preference assessments; (b) all three participants who passed both visual and visual matching-to-sample discrimination assessments, but failed the auditory-visual discrimination assessment on the ABLA test could consistently select their most preferred item in both object and picture preference assessments but not when the choices were spoken; and (c) all three participants who passed the visual, visual matching-to-sample, and auditory-visual discrimination assessments on the ABLA test could consistently select their most preferred item in all three modalities. In the second experiment when non-food items were presented, Conyers et al. observed similar results for seven of the nine participants with mixed results obtained for two participants with visual and visual matching-to-sample discriminations.

Schwartzman, Yu, and Martin (2003) replicated the results of Conyers et al. (2002) using food items with six adults with developmental disabilities, and Clevenger and Graff (2005) showed that object-to-picture and picture-to-object matching skills might be prerequisite skills for making consistent choices in preference assessments involving pictures of food items. In addition, de Vries et al. (2005) systematically replicated the procedures of Conyers et al. using leisure activities with persons with developmental disabilities. They found that eight of the nine participants in their study showed a preference for their preferred activities in two-choice preference assessments when stimulus modalities “matched” their discrimination skills. Most recently, Reyer and Sturmey (2006) also partially replicated the procedures of Conyers et al. using work tasks with adults with developmental disabilities and intellectual disability. These studies underscore the importance of matching stimulus modalities used in preference assessments to the discrimination skills of individuals.

However, many leisure activities and work tasks are protracted and involve multiple stimuli that may be impractical or impossible to present in object or pictorial modalities. Object and pictorial presentations are relatively static and may not adequately present the various aspects of an activity. Moreover, the stimuli captured by object and pictorial presentations may not be the reinforcing aspects of an activity for the individual. It may be possible to overcome these limitations by using video presentations.

Recent studies have investigated the effectiveness of video presentation in identifying job preferences for individuals with developmental disabilities. For example, Ellerd, Morgan, and Salzberg (2002) measured the job preferences of four verbal adults with developmental disabilities. They provided five job options via video presentations using single-stimulus and paired-stimulus presentation procedures in the first and the second preference assessments respectively for each participant. Ellerd et al. observed differential preferences for all participants; however, the assessment using paired-stimulus presentation procedure was more sensitive in identifying a preference hierarchy than the single-stimulus presentation procedure. Stock et al. (2003) examined the effectiveness of a computer-based job preference assessment of 25 adults with intellectual disabilities. In the assessment, participants engaged in a self-paced computer program in which they were allowed to watch videos representing different job options and were allowed to make choices among the two-choice presentation trials. Results indicated that in general, job preferences identified by the computer-based preference assessment were positively correlated to the preferences predicted by the educators and agency professionals who relied on the participants’ previous assessment results and their past experience with the participants. The same educators and agency professionals agreed that the computer-based job preference assessment was more effective than the most popular job assessment tools in the existing job placement system (e.g., Career Decision Maker). Stock et al. explained that because video presentation provided more information about jobs than picture and verbal presentations, individuals had a better understanding among job options before making any decision. The functioning levels of participants in the above studies were not reported although they appeared to be relatively high functioning. Individuals in the Ellerd et al. study were verbal and those in the Stock et al. study were able to follow instructions to interact with the computer program. It is unclear whether individuals with more severe disabilities, with no speech or auditory discriminations, could respond to video stimuli in preference assessments.

Considering the relationship between discrimination skills and stimulus modalities used in preference assessments reported in previous research, and the potential of video presentations in presenting protracted activities, the purpose of this study was to systematically replicate previous research on discrimination skills and object, pictorial, and spoken stimuli in assessing preferences for leisure activities, and to include video presentation as one of the stimulus modalities.

Method

Participants and Setting

Participants were seven adults recruited from River Road Place of St. Amant, a residential and community resource facility for persons with developmental disabilities. They were selected based on their ABLA assessments conducted at the beginning of the study. The ABLA assessment procedures can be found in Conyers et al. (2002), de Vries et al. (2005), and Martin and Yu (2000). Participants 1, 2, and 3 passed the visual discrimination task (referred to as Level 3 on the ABLA test) but failed both the visual matching-to-sample (Level 4) and the auditory-visual discriminations (Level 6). Participants 4 and 5 passed both Levels 3 and 4, but failed Level 6. Participants 6 and 7 passed all three levels. Characteristics for each participant were obtained from their health records and are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Participant | Sex | Age | Diagnosis | Communication Skills | ABLA Levels Passed* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 41 | Severe developmental disabilities | None | 3 |

| 2 | F | 39 | Profound developmental disabilities | None | 3 |

| 3 | M | 33 | Autism | None | 3 |

| 4 | F | 37 | Severe developmental disabilities | None | 3 and 4 |

| 5 | M | 49 | Severe developmental disabilities | Little speech; socially responsive | 3 and 4 |

| 6 | F | 41 | Severe developmental disabilities | Little speech; difficult to understand | 3, 4, and 6 |

| 7 | F | 50 | Moderate developmental disabilities | Little or no recognizable speech; understands simple instructions and questions | 3, 4, and 6 |

Level 3 = visual discrimination, Level 4 = quasi-identity visual matching-to-sample discrimination, Level 6 = auditory-visual discrimination.

All sessions were conducted in a small quiet room with minimal distractions. The experimenter sat across a table from the participant during each session, and an observer attended some of the sessions to conduct reliability checks.

Research Design

Each participant received an initial preference assessment using actual objects to identify his or her most preferred and least preferred leisure activities. Next, the most and least preferred leisure activities were presented in four modalities (object, picture, video, and spoken) using a replication design, with each modality assessed at least twice.

Initial Object Preference Assessment

Six activities were identified for each participant based on recommendations from the participant’s caregivers and on practical considerations in presenting and performing the activities during sessions. Table 2 lists all the leisure activities used and the object stimuli presented on each trial.

TABLE 2.

Leisure Activities Used in the Preference Assessments

| Leisure Activity | Stimuli Presented During a Trial |

|---|---|

| Coloring | Crayons and coloring book |

| Doing a puzzle | 3-pieces |

| Listening to music | Tape recorder with pop music |

| Painting | Paint, paint brush, paper, and water |

| Playing cards | Deck of playing cards |

| Playing with a light toy | Rattle-shaped light toy called “Meteor Storm” about 20 cm tall |

| Playing with object-sound related toy | A cow-shaped plastic toy |

| Playing with a velcro-ball | Tennis ball wrapped with velcro and two rackets with velcro on one side |

| Playing with a carpentry set | Mini tool kit |

| Playing with a toy car | A miniature sport car about 6 cm long |

| Playing with a xylophone | A miniature xylophone (24 cm × 11 cm) |

| Reading magazines | Three types of magazines |

| Shaking a rattle | Rattle |

| Touching a lighting ball | Plasma lighting ball about 33 cm tall |

| Turning on and off a fan that lights up | Battery operated hand-held fan |

| Washing and applying lotion to hands | Hand soap, sponge, water and hand lotion |

| Watering plants | Plastic plants and watering can |

A paired-stimulus presentation procedure was used (Fisher et al., 1992; Piazza, Fisher, Hagopian, Bowman, & Toole, 1996). Each stimulus was paired with every other stimulus twice, totaling 30 trials. Order and positions of the stimuli were counterbalanced across trials. Trials were spread across two to four sessions depending on the participant’s level of functioning. On each trial, the experimenter presented the objects representing the two leisure activities concurrently on the table. Verbal prompts and gestures were provided to the participant to attend to each stimulus. The experimenter then asked the participant to “pick one”. Once the participant made an approach response (touching or pointing to a stimulus), the non-selected stimulus was removed immediately, and the participant was allowed to engage in the chosen activity for approximate 30 s. If the participant tried to approach both stimuli or did not choose an activity after 10 s, the trial was repeated.

At the end of the assessment, the preference measure for a stimulus was calculated by dividing the number of trials in which that stimulus was chosen by the total number of trials that particular stimulus was available during the assessment, multiplied by 100%. The most and least frequently preferred stimuli were used in the next phase (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Percentage of Trials that the Most and Least Frequently Preferred Activities Were Chosen for Each Participant During the Initial Object Preference Assessment

| Participant | Most Frequently Chosen Activity | % | Least Frequently Chosen Activity | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Touching a lighting ball | 70 | Watering plants | 10 |

| 2 | Playing with a velcro-ball | 70 | Watering plants | 20 |

| 3 | Playing with a toy car | 70 | Coloring | 20 |

| 4 | Watering plants | 70 | Listening to music | 40 |

| 5 | Playing with a carpentry set | 80 | Playing with a velcro-ball | 20 |

| 6 | Playing with a light toy | 100 | Coloring | 20 |

| 7 | Playing with a light toy | 70 | Washing and applying lotion to hands | 30 |

Stimulus Modalities and Presentation Procedures

Four stimulus modalities were evaluated in a replication design. Presentations using objects (O) were given to each participant during the first phase, followed by presentations using pictorial (P), video (V), and spoken (S) stimuli in subsequent phases. The order for P, V, and S phases was randomized and the four phases were then repeated for each participant. Additional replications were conducted for three participants because their results were varied across phases and inconsistent with our predictions. In all modalities, activities were presented using a paired-stimulus procedure, and the most and least preferred leisure activities identified during the initial object preference assessment were used on each trial. Each phase consisted of two sessions, with six trials per session. The left-right positions of the two leisure activities were counterbalanced across trials within each phase.

Object presentation

During the object phase, the presentation procedures were the same as in the initial object preference assessment except that only two items, representing the most and the least preferred activities were used.

Pictorial presentation

During the pictorial phase, the presentation procedures were similar to the object phase except colored pictures (22 cm × 27 cm) of the object stimuli were shown on each trial. At the beginning of each trial, the two colored pictures were placed, side by side, face down on the table in front of the participant. The experimenter held up the picture on the left to the participant’s eye level and said, “look”. Once the participant looked at the picture, the experimenter placed the picture on the table faced down, and repeated the procedure for the picture on the right. The experimenter then held up both pictures simultaneously and asked the participant to “pick one”. After the participant made a selection, the pictures were removed and the chosen activity was provided immediately to the participant for 30 s.

Video presentation

During the video phase, the presentation procedures were similar to the picture phase except that video clips of the leisure activities were presented instead of the colored pictures. On each trial, the experimenter first presented the video for the activity on the left side of a 43 cm monitor while the right side was blank, and asked the participant to look at the video, while pointing to the video. Once the participant looked at the video, the experimenter repeated the procedure for the activity on the right side of the monitor. Then, the experimenter played both videos simultaneously and asked the participant to “pick one”. Once the participant pointed to one of the two videos, the experimenter turned off the computer screen and provided the chosen activity to the participant for 30 s. The sound was turned off for all video presentations.

Spoken presentation

During the spoken phase, the presentation procedures were the same as in the picture phase except that two sheets of white paper were used instead of the pictures and the experimenter stated the names of the activities. At the beginning of each trial, the experimenter held up the paper to the left of the participant’s eye level, stated the name of the activity in a neutral tone, and put the paper back on the table. This was repeated with the paper/activity on the right. Then, the experimenter held up both papers and asked the participant to “pick one”. After the participant made an approach response (e.g., pointing to the paper), both papers were removed and the activity that corresponded to the selected paper was provided to the participant for 30 s.

Reliability Assessments

ABLA discrimination assessment

Interobserver reliability checks were conducted on the initial ABLA discrimination assessments for all participants. The experimenter and an observer independently recorded the participant’s response on each trial during the assessment. Agreement on a trial was defined as the experimenter and the observer both recording the same response; otherwise, it was considered a disagreement. Percent agreement for each discrimination task was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements, and then multiplying by 100% (Martin & Pear, 2007). Percent agreement was 100% for all participants.

The observer also conducted procedural integrity checks using a pre-defined checklist, which included whether the testing materials were placed in the correct positions, verbal instructions were provided correctly, correction procedures were conducted properly following an incorrect response, and reinforcers were given immediately following a correct response. A trial was scored as correctly delivered if no errors were made. Procedural integrity was 100% for all participants.

Initial object preference assessment

Interobserver reliability checks were conducted for each participant and the percentage of trials observed by a second observer ranged from 23% to 100% across participants. The experimenter and the observer recorded the participant’s selection on each trial. The mean percent agreement across participants was 99%, with a range of 86% to 100%.

Procedural integrity checks for preference assessment were also conducted for each participant and the percentage of trials observed by a second observer ranged from 23% to 100% across participants. On each trial, the observer recorded whether the correct stimuli were presented and in the correct positions, whether correct verbal cues were provided, and whether the consequence was delivered properly following a selection. A trial was scored as correct if no errors occurred. The mean percentage of trials delivered correctly across participants was 100%.

Stimulus modalities presentation

Interobserver reliability checks were conducted for each participant and for each modality. The percentage of sessions observed ranged from 25% to 100% across participants. A trial was scored as an agreement only if both the experimenter and the observer recorded the same response. The mean percent agreement across sessions and participants was 99%, with a range of 96% to 100%.

Procedural integrity checks were also performed for each participant and the percentage of sessions observed ranged from 25% to 100% across participants. Each trial was scored using a checklist similar to the one used described above for preference assessment. A trial was considered correctly delivered if all the steps on the checklist were performed correctly. The mean percentage of trials delivered correctly across sessions and participants was 99%, ranging from 99% to 100%.

Results

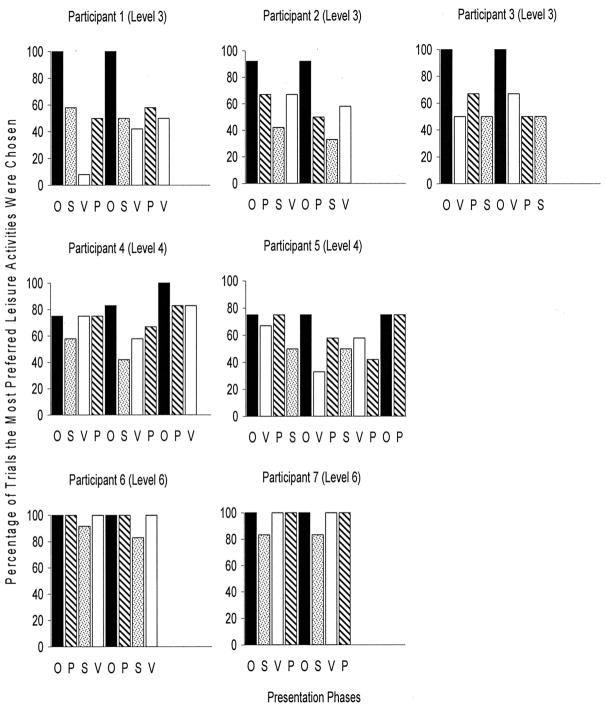

Figure 1 shows the percentage of trials that each participant chose their most preferred leisure activity for each presentation method. The top three graphs show the results of Participants 1 through 3, who passed the visual discrimination assessment (Level 3) but failed both visual matching-to-sample (Level 4) and auditory-visual (Level 6) discriminations on the ABLA Test. During object presentation phases, the participants selected their most preferred leisure activity on an average of 97% across phases (range 92% to 100%). During the pictorial presentation phases, the average was 57% (range 50% to 67%), which is approximately chance level in a two-choice arrangement. During the video presentation phases, the average was 49% (range 8% to 67%). Except for the first video phase for Participant 1, who showed a low preference for the high preference activity (8%), preference levels for the preferred activity during subsequent phases and for the other participants were approximately chance level. During the spoken presentation phases, preference for the preferred activity averaged 47% (range 33% to 58%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of trials that the most preferred leisure activity was chosen during object (O), pictorial (P), video (V), and spoken (S) presentation phases for each participant. Participants at Level 3 passed only the visual discrimination, participants at Level 4 passed both visual and visual matching-to-sample discriminations, and participants at Level 6 passed visual, visual matching-to-sample, and auditory-visual discriminations.

Results of Participants 4 and 5, who passed both visual and visual matching-to-sample discrimination assessments, but failed the auditory-visual discrimination assessment on the ABLA Test, are shown in the second row of Figure 1. During object presentation phases, the two participants selected their most preferred leisure activity on an average of 80% across phases (range 75% to 100%). During the pictorial presentation phases, the average was 68% (range 42% to 83%). In the video presentation phases, the average was 62% (range 33% to 83%). Lastly, in the spoken phases, the average was 50% (range 42% to 58%).

Participants 6 and 7 passed the visual, visual matching-to-sample, and auditory-visual discrimination assessments on the ABLA Test. They selected their preferred activity on all trials (100%) during object, pictorial, and video phases, and on an average of 85% of the spoken phase trials (range 83% to 92%).

Discussion

Concerning the object, pictorial, and spoken modalities, the results replicate the findings of previous research except for the pictorial modality with Participant 5. First, we anticipated that Level 3 participants would select their preferred activity more frequently during object phases, but at approximately chance level during pictorial and spoken phases. This was confirmed. Second, we anticipated that Level 4 participants would select their preferred activity more frequently during object and pictorial phases, but at approximately chance level during spoken phases. This was confirmed except for the pictorial modality with Participant 5. His preference toward the preferred leisure activity was inconsistent during pictorial phases. He selected his preferred activity on an average of 63% across phases. Participant 5 did not select his preferred activity during object phases as frequently as other participants (i.e., on an average of 75% across phases vs. on an average of 96% across phases for other participants). This suggests that the activity was not as strongly preferred and this may have contributed to the mixed results. Overall, Participant 4 selected her preferred leisure activity during pictorial phases more frequently even though her preference toward the preferred activity was inconsistent across phases and the effect is small (i.e., on an average of 75% across phases). Third, we anticipated that the Level 6 participants would select their preferred activity more frequently during all three stimulus modalities. This was confirmed in all modalities. Except for Participant 5’s performance in the pictorial modality, these results are consistent with previous findings (e.g., Conyers et al., 2002; de Vries et al., 2005).

The present study extends previous research by examining the use of video presentations in preference assessments with persons with severe and profound developmental disabilities. During video presentations, all participants at Level 3 did not show a preference for their preferred over the less preferred activities, while both participants at Level 6 chose their preferred activities consistently. The two participants at Level 4 showed mixed results, with Participant 4 choosing her preferred activity more frequently than the less preferred activity even though her performance was inconsistent across phases, whereas Participant 5 did not. Given the small number of participants, these results should be interpreted cautiously. Further research with additional participants, especially at Level 4, is needed. However, if the present results are generalizable, it suggests that quasi-identity matching performance involving 3-dimensional objects (the ABLA Level 4 discrimination) may not predict a person’s ability to consistently select his/her preferred activity using video presentation.

Research is needed to examine the relative importance of the visual and auditory components of video presentations. In this study, the video clips were presented without sound because we speculated that sounds associated with the two videos presented concurrently might have been confusing to the participants, especially those who had not passed the auditory-visual discrimination (Level 6) on the ABLA Test. However, sounds and visual stimuli associated with different activities usually occur as a compound stimulus in the natural environment and one is often exposed to multiple stimuli simultaneously. For the Level 4 participants, who had failed to perform the ABLA Level 6 auditory-visual discrimination, it is quite possible that they may be able to discriminate some non-speech sounds. Therefore, distinctive sounds accompanying different activities might facilitate video discriminations even for participants who have not demonstrated the ABLA Level 6 discrimination. Alternatives to concurrent presentations of videos with sound, such as successive presentations, may help to reduce potential interference.

Research on video presentation in preference assessment has been limited for persons with severe developmental disabilities, and the relationship between discrimination skills and the effectiveness of the video presentation in preference assessments has been unexplored. The potential of video presentation appears to lie in its ability to present complex activities more accurately (Ellerd et al., 2002; Stock et al., 2003). It is possible that individuals with severe developmental disabilities who have difficulties responding to pictorial and spoken stimuli in preference assessments could respond to or learn to respond to video presentations more readily. Thus, future research is much needed to examine the conditions under which video presentation will be most effective (relative to other modalities) and to develop effective procedures to teach individuals to indicate their preferences by responding to video presentations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for their cooperation throughout the study, and Leah Enns, Sara Spevack, Aynsley Verbeke, Kerri Walters, and Georgina Johnston for their assistance with reliability assessments. This research was supported by grant MOP77604 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- Clevenger TM, Graff RB. Assessing object-to-picture and picture-to-object matching as prerequisite skills for pictorial preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:543–547. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.161-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conyers C, Doole A, Vause T, Harapiak S, Yu CT, Martin GL. Predicting the relative efficiency of the three presentation methods for assessing performances of persons with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:49–58. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries C, Yu CT, Sakko G, Wirth KM, Walters KL, Marion C, et al. Predicting the relative efficacy of verbal, pictorial, and tangible stimuli for assessing preferences of leisure activities. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2005;110:145–154. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110<145:PTREOV>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerd DA, Morgan RL, Salzberg CL. Comparison of two approaches for identifying job preferences among persons with disabilities using video CD-ROM. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. 2002;37:300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CW, Reid DH, White LK, Halford RC, Brittain DP, Gardner SM. Identifying reinforcers for persons with profound handicaps: Staff opinion versus systematic assessment of preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21:31–43. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Hwang B, Kim JH, Eisenman LT, Killian DJ. Quality of life in applied research: A review and analysis of empirical measures. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1995;99:623–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr N, Meyerson L, Flora J. The measurement of motor, visual and auditory discrimination skills. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1977;24:156–170. [Google Scholar]

- Logan KR, Jacobs HA, Gast DL, Smith PD, Daniel J, Rawls J. Preferences and reinforcers for students with profound multiple disabilities: Can we identify them? Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2001;13:97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Martin GL, Pear J. Behavior modification: What it is and how to do it. 8. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martin GL, Yu DCT. Overview of research on the Assessment of Basic Learning Abilities Test. Journal on Developmental Disabilities. 2000;7:10–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pace GM, Ivancic MT, Edwards GL, Iwata BA, Page TJ. Assessment of stimulus preference and reinforcer value with profoundly retarded individuals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18:249–255. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza CC, Fisher WW, Hagopian LP, Bowman LG, Toole LT. Using a choice assessment to predict reinforcer effectiveness. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:1–9. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyer HS, Sturmey P. The Assessment of Basic Learning Abilities (ABLA) Test predicts the relative efficacy of task preferences for persons with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:404–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzman L, Yu CT, Martin GL. Choice responding as a function of choice presentation method and level of preference in persons with developmental disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Community, and Rehabilitation. 2003;1(3):Article 3. Retrieved March 15, 2003, from http://www.ijdcr.ca/VOL01_03_CAN/articles/schwartzman.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- Stock SE, Davies DK, Secor RR, Wehmeyer ML. Self-directed career preference selection for individuals with intellectual disabilities: Using computer technology to enhance self-determination. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2003;19:95–103. [Google Scholar]