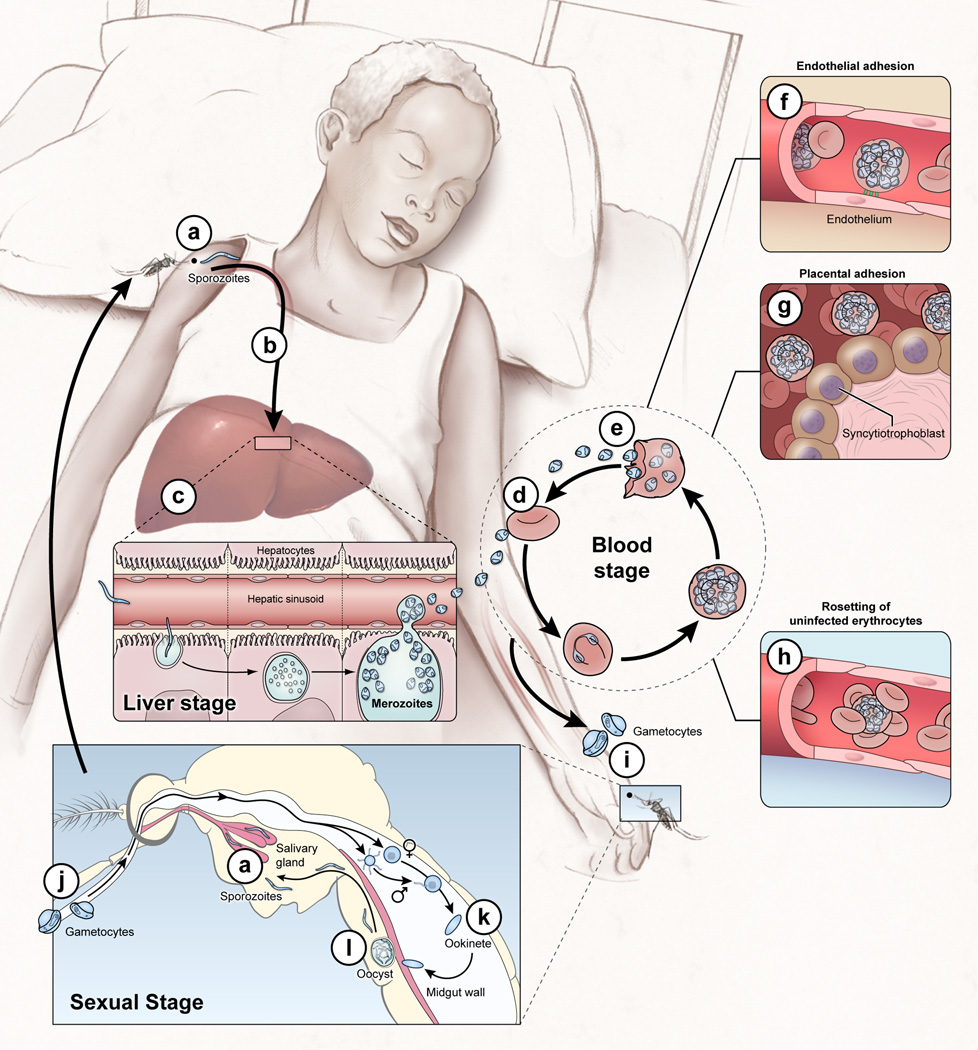

Figure 1. The P. falciparum life cycle: no shortage of Ab targets.

The P. falciparum life cycle in humans includes the asymptomatic liver stage; the blood stage which causes disease; and the sexual gametocyte blood stage which infects mosquitoes that transmit the parasite. Infection begins when Anopheles mosquitos inject sporozoites into the skin and blood (a) which migrate to the liver and invade a small number of hepatocytes (b). Each sporozoite gives rise to thousands of asexual parasites called merozoites (c). ~1 week after hepatocyte invasion merozoites exit the liver into the bloodstream and begin a 48 hr cycle (d) of RBC invasion, replication, RBC rupture, and merozoite release (e). Once inside RBCs the parasite exports variant surface antigens (VSAs) such as PfEMP1 to the RBC surface. VSAs mediate binding of iRBCs to the microvascular endothelium of various organs (f) and placental tissue (g) allowing parasites to avoid splenic clearance and promoting the inflammation and circulatory obstruction associated with clinical syndromes such as cerebral malaria (coma) and pregnancy-associated malaria. VSA-mediated rosetting (binding of iRBCs to RBCs) may also contribute to disease (h). A small number of blood-stage parasites differentiate into sexual gametocytes (i) which are taken up by mosquitos (j) where they differentiate into gametes that fuse to form a motile zygote, the ookinete (k), where meiosis occurs. The ookinete crosses the midgut wall and forms an oocyst (l) that develops into sporozoites that enter the mosquito salivary gland to complete the life cycle (a).

Abs that sterilely protect by neutralizing sporozoites (a) and/or blocking hepatocyte invasion (b) are rarely if ever acquired through natural infection (4). Abs induced by the RTS,S vaccine target the circumsporozoite (CS) protein on the sporozoite surface (98) and correlate with sterile protection in malaria-naïve adults (99); but in African children RTS,S generally protects against disease not infection and the correlation between Abs and protection is less clear (100, 101). Abs are a key component of naturally-acquired blood stage immunity (7) but the Ag targets and mechanisms of protection are incompletely understood and likely multifaceted. Abs may contribute to protection by clearing merozoites (102) and iRBCs (e) through opsonization (103) or complement-mediated lysis (104); inhibiting merozoite invasion of RBCs (d) (105); and/or blocking adhesion of iRBCs to vascular endothelium (f) (106). Non-neutralizing Abs may contribute to protection through Ab-dependent monocyte-(107) or NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Blood stage vaccines have focused primarily on generating Abs to merozoite proteins but with limited success (54, 108), probably due to Ag polymorphism (14, 108) and redundant RBC invasion pathways (109). Of note, the conserved merozoite protein PfRh5 appears to be essential for RBC invasion (80) and may be susceptible to vaccine-inducible cross-strain neutralizing Ab (110). Protection from pregnancy-associated malaria correlates with IgG specific for VAR2CSA, a conserved protein which mediates adherence to placental tissue (g) (111). Vaccine-induced Abs targeting Ags on gametocytes and gametes that are ingested with the blood meal (i–l) could prevent parasite development in the mosquito and block or reduce transmission (112).