Abstract

Aims

Statins reduce LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) and the risk of vascular events, but it remains uncertain whether there is clinically relevant genetic variation in their efficacy. This study of 18 705 individuals aims to identify genetic variants related to the lipid response to simvastatin and assess their impact on vascular risk response.

Methods and results

A genome-wide study of the LDL-C and apolipoprotein B (ApoB) response to 40 mg simvastatin daily was performed in 3895 participants in the Heart Protection Study, and the nine strongest associations were tested in 14 810 additional participants. Selected candidate genes were also tested in up to 18 705 individuals. There was 90% power to detect differences of 2.5% in LDL-C response (e.g. 42.5 vs. 40% reduction) in the genome-wide study and of 1% in the candidate gene study. None of the associations from the genome-wide study was replicated, and nor were significant associations found for 26 of 36 candidates tested. Novel lipid response associations with variants in LPA, CELSR2/PSRC1/SORT1, and ABCC2 were found, as well as confirmatory evidence for published associations in LPA, APOE, and SLCO1B1. The largest and most significant effects were with LPA and APOE, but were only 2–3% per allele. Reductions in the risk of major vascular events during 5 years of statin therapy among 18 705 high-risk patients did not differ significantly across genotypes associated with the lipid response.

Conclusions

Common genetic variants do not appear to alter the lipid response to statin therapy by more than a few per cent, and there were similar large reductions in vascular risk with simvastatin irrespective of genotypes associated with the lipid response to simvastatin. Consequently, their value for informing clinical decisions related to maximizing statin efficacy appears to be limited.

Keywords: Pharmacogenetics, Statins, LDL-C, ApoB

See page 949 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs439)

Introduction

Statin therapy is a widely prescribed, well-tolerated, and effective approach to lowering blood levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and the risk of vascular events.1 Standard statin regimens typically reduce LDL-C by ∼40%,2 and greater absolute reductions in LDL-C produce greater reductions in the risk of major vascular events.1 The lipid response to statins is perceived to vary between individuals and to have genetic influences,3 but reliable large-scale evidence of pharmacogenetic interactions and the impact on the risk response to statins is limited. Therefore, it remains unclear whether genetic variation is relevant to the effects and clinical management of statin therapy.

Genetic associations with the lipid response to statin therapy have been reported (for example with APOE, SLCO1B1, LPA, PCSK9, and HMGCR), but their effects have been relatively modest and most have been inconsistently replicated.4–18 Furthermore, little is known about the impact of variants associated with lipid response on the reduction in vascular risk with statin therapy. The majority of previous studies of lipid response to statin have adopted a candidate-gene approach.6–9,12–14,16 Hypothesis-free genome-wide investigations of the lipid response to statin have only been reported in a total of ∼10 000 individuals for LDL-C response and ∼3500 individuals for apolipoprotein B (ApoB) response.4,5,15,18 The most convincing lipid response associations have been in genes with validated associations for statin-related adverse events or lipid levels.19,20 In addition, genes related to statin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics,3,21 and coronary heart disease (CHD) risk22,23 are plausible candidates for variation in response to statin therapy.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the associations of common genetic variants with response to statin therapy. It includes genome-wide association analyses of the LDL-C and ApoB responses to 40 mg simvastatin daily in 3895 participants in the Heart Protection Study and independent testing in a further 14 810 of the participants. The effects of selected candidate genes on the lipid response to statins were also assessed in up to 18 705 participants. Finally, the effects of variants that affected lipid response on the reductions in major vascular events produced by statin therapy were assessed among 18 705 genotyped patients randomly allocated simvastatin vs. placebo for an average of 5 years.

Methods

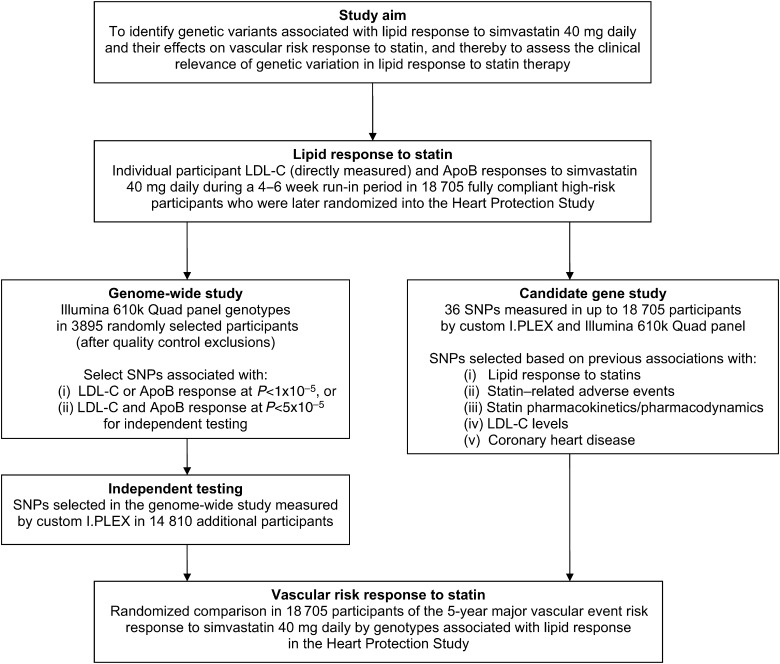

The design of the study is outlined in Figure 1 and further details are provided below.

Figure 1.

Study design outline.

The Heart Protection Study

Between 1994 and 1997, 20 536 men and women aged 40–80 years were recruited from 69 collaborating hospitals in the UK (with ethics committee approval). Participants were eligible for inclusion if they had non-fasting blood total cholesterol concentrations of at least 3.5 mmol/L (135 mg/dL) and either a previous diagnosis of coronary disease, ischaemic stroke, other occlusive disease of non-coronary arteries, diabetes mellitus, or (if men 65 years or older) treated hypertension. Patients were not on statin therapy at entry into the study. At the screening visit, all participants provided written consent and began a pre-randomization ‘run-in’ phase involving 4 weeks of placebo followed by 4–6 weeks of 40 mg simvastatin daily, after which fully compliant individuals were randomly allocated to 40 mg simvastatin daily or matching placebo for ∼5 years. A non-fasting blood sample was taken at screening (i.e. before starting any statin therapy) and at the end of run-in (i.e. while on 40 mg simvastatin daily). The pre-specified primary outcome for assessing the effect of statin therapy in different subgroups was the first occurrence after randomization of an incident major vascular event (defined as either non-fatal MI or coronary death, coronary or non-coronary revascularizations, or any stroke). Further details of the Heart Protection Study are reported elsewhere.24,25

Laboratory methods

In the central laboratory, Beckman autoanalysers used standard spectrophotometric enzymatic methods to measure total cholesterol and lipid fractions (including LDL-C directly) and immunoturbidometric methods to measure ApoB. Coefficients of variation for lipid measurements were typically <5%.

Genotyping methods

Genome-wide study

A random selection of 4000 self-reported Caucasians with lipids and other biomarker measurements were selected, and genotypes measured using the Illumina 610K Quad panel. Genome-wide data were available for 3895 individuals after quality control exclusions including inadequate DNA, discrepant sex, repeated samples, and poor (<95%) genotyping success rate. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with <0.5% minor allele frequency, <95% call rate, or significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P < 5 × 10−7) were excluded, leaving a total of 546 210 SNPs for analysis. Single nucleotide polymorphisms from the genome-wide analysis were selected for independent testing if P < 1 × 10−5 for associations with either the LDL-C or the ApoB response to simvastatin therapy, or if P < 5 × 10−5 for both the LDL-C and ApoB responses. The SNPs selected from the genome-wide analysis were genotyped using custom I.PLEX panels in the remaining 14 810 participants in the Heart Protection Study with available DNA.

Candidate gene study

Single nucleotide polymorphisms in loci that had previously been associated with lipid response, statin pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics, statin-related side-effects, LDL-C levels, or CHD risk were selected for the candidate gene study.4,5,12,15,18–23 Thirty-six candidate SNPs were custom genotyped including 33 SNPs using I.PLEX panels in the 14 810 individuals used for independent testing in the genome-wide study and a further 3 SNPs (rs4149056 and rs2306283 in SLCO1B1 and rs4299376 in ABCG5/8) in previous experiments in the same individuals.19,22 Data were also available for most of these variants from the genome-wide panel, yielding directly measured genotypes in up to 18 705 individuals. To allow for multiple comparisons, a threshold of P < 0.001 was taken to indicate statistical significance for these candidate SNPs. For completeness, the remaining literature-based candidate loci that were not selected for custom genotyping4,5,12,15,18–23 were examined directly or in proxy SNPs26 in the genome-wide data where possible.

Additional information

Quality control details and allele frequencies for SNPs selected for custom genotyping are shown separately for the genome-wide panel and custom genotyping data in the Supplementary material online, Table S1. The results for SNPs showing deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (rs857252 and rs9982601) should be interpreted with caution. The minor allele was coded as the effect allele in all analyses and chromosomal positions were based on NCBI build 36.

Statistical methods

The proportional LDL-C or ApoB responses were defined by the changes in loge lipid levels from the screening visit prior to starting statin therapy (‘off-statin’) to the randomization visit following 4–6 weeks on 40 mg simvastatin daily (‘on-statin’) in compliant individuals. Linear regression was used to estimate the associations between genetic variants and lipid response to statin. The additional per cent reduction per allele was calculated as 100 × exp(M) × (1-exp(β)), where β is the regression estimate of the per allele effect on the change in the log lipid level and M is the overall mean change in the log lipid level. Percentage lipid reductions within comparison groups were estimated as 100 × (1-exp(Mg)), where Mg denotes the mean change in the log lipid level within the group. Standard errors (SEs) were estimated from the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Secondary analyses included estimating the associations with the absolute lipid response to statin and with off-statin lipid levels. Where appropriate, genotype scores summarizing the available information at a locus were calculated based on previously published methods or joint regression analyses. Lipid response estimates for candidate SNPs were calculated using all available genotype data from the different genotyping platforms (after quality control analyses showed no heterogeneity between the results). Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the effects of genotypes on the proportional risk response to simvastatin during the randomized phase of the Heart Protection Study. Differences in the proportions of events were used to estimate the absolute risk response to statin. All analyses were performed using PLINK (version 1.07) and SAS (version 9).

Results

In the 18 705 genotyped participants, the mean off-statin and on-statin LDL-C levels during the pre-randomized phase were 3.37 and 1.98 mmol/L, respectively (Table 1). On average, compliance with 40 mg simvastatin daily for 4–6 weeks resulted in a 42.4% reduction in LDL-C and a 32.8% reduction in ApoB. In absolute terms, this corresponded to a 1.39 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C and 0.37 g/L reduction in ApoB. Additional characteristics are shown in the Supplementary material online, Table S2.

Table 1.

Mean (95% CI) lipid levels and lipid response in 18 705 genotyped participants

| Off-statin | On-statin | Response to 40 mg simvastatin daily |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportional reduction | Absolute reduction | |||

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.37 (3.36, 3.38) | 1.98 (1.97, 1.99) | 42.4% (42.2, 42.6%) | 1.39 (1.38, 1.40) |

| ApoB (g/L) | 1.14 (1.14, 1.14) | 0.77 (0.77, 0.78) | 32.8% (32.6, 32.9%) | 0.37 (0.36, 0.37) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.06 (1.06, 1.07) | 1.05 (1.04, 1.05) | 1.3% (1.1, 1.5%) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) |

| ApoA1 (g/L) | 1.19 (1.19, 1.20) | 1.22 (1.22, 1.22) | −2.0% (−2.2, −1.9%) | −0.02 (−0.03, −0.02) |

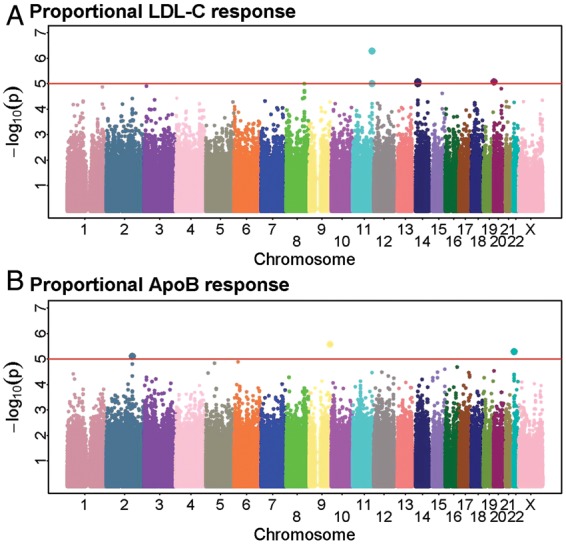

Lipid response to statin in the genome-wide association study

This genome-wide association study in 3895 individuals had 90% power to detect a 2.5% difference (e.g. 42.5 vs. 40%) in the LDL-C response in SNPs with 15% minor allele frequency and to detect even smaller differences in more common SNPs. The QQ plot of the association P-values did not indicate an excess of significant results compared with those expected by chance alone (Supplementary material online, Figure S1) and only nine SNPs passed the pre-defined threshold for independent testing (Figure 2). Of these, eight SNPs were successfully genotyped in an additional 14 810 individuals and the one (rs17510813) that failed genotyping was strongly correlated (r2 = 0.8) with a SNP (rs17595975) that was successfully genotyped. None of these SNP associations was, however, confirmed in the independent data set (all P > 0.05; Table 2).

Figure 2.

The genome-wide Manhattan plot of associations with proportional (A) LDL cholesterol response and (B) apolipoprotein B response to 40 mg simvastatin daily in 3895 individuals. Single nucleotide polymorphisms with P < 1 × 10−5 for either LDL cholesterol or apolipoprotein B response, or if P < 5 × 10−5 for both LDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B response associations were selected for independent testing. A reference line has been plotted at P = 1 × 10−5.

Table 2.

Proportional lipid response associations (per allele) for the top-hits from the genome-wide analyses that were selected for custom genotyping in independent samplesa

| SNP | Chr | Nearby gene(s)/locus | Effect/other allele | Genome-wide analysis |

Independent testing |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect allele freq | n | Additional % reductionb (95% CI) | P-value | n | Additional % reductionb (95% CI) | P-value | ||||

| LDL-C response | ||||||||||

| rs10497323 | 2 | XIRP2 | C/T | 0.16 | 3894 | −1.58 (−2.39, −0.78) | 9.9 × 10−5 | 14 454 | 0.21 (−0.23, 0.65) | 0.35 |

| rs3749004 | 2 | XIRP2 | G/A | 0.11 | 3887 | −1.96 (−2.91, −1.02) | 3.8 × 10−5 | 14 371 | 0.23 (−0.29, 0.74) | 0.39 |

| rs7047055 | 9 | MED27 | T/C | 0.49 | 3888 | 1.20 (0.62, 1.77) | 5.3 × 10−5 | 13 354 | −0.16 (−0.49, 0.17) | 0.34 |

| rs9888300 | 11 | 11q24 | C/A | 0.39 | 3888 | 1.50 (0.92, 2.07) | 5.3 × 10−7 | 14 405 | −0.11 (−0.44, 0.21) | 0.49 |

| rs10893006 | 11 | 11q24 | T/C | 0.34 | 3849 | 1.38 (0.77, 1.97) | 9.9 × 10−6 | 14 413 | −0.07 (−0.40, 0.26) | 0.67 |

| rs17510813 | 14 | SRP54/FAM177A1 | T/C | 0.12 | 3893 | −2.07 (−3.00, −1.15) | 8.4 × 10−6 | |||

| rs17595975 | 14 | SRP54/FAM177A1 | T/G | 0.11 | 3873 | −2.17 (−3.15, −1.20) | 9.8 × 10−6 | 14 115 | −0.19 (−0.71, 0.32) | 0.47 |

| rs857252 | 20 | UBOX5/FASTKD5 | G/T | 0.38 | 3891 | −1.39 (−2.01, −0.77) | 8.6 × 10−6 | 13 628 | −0.07 (−0.41, 0.26) | 0.67 |

| rs5759068 | 22 | 22q11 | T/C | 0.39 | 3872 | −1.25 (−1.87, −0.64) | 5.4 × 10−5 | 14 446 | −0.16 (−0.49, 0.16) | 0.33 |

| ApoB response | ||||||||||

| rs10497323 | 2 | XIRP2 | C/T | 0.16 | 3894 | −1.52 (−2.20, −0.85) | 8.0 × 10−6 | 14 454 | 0.03 (−0.35, 0.40) | 0.89 |

| rs3749004 | 2 | XIRP2 | G/A | 0.11 | 3887 | −1.62 (−2.41, −0.83) | 4.7 × 10−5 | 14 371 | 0.10 (−0.34, 0.54) | 0.65 |

| rs7047055 | 9 | MED27 | T/C | 0.49 | 3888 | 1.17 (0.69, 1.66) | 2.6 × 10−6 | 13 354 | −0.03 (−0.32, 0.25) | 0.82 |

| rs9888300 | 11 | 11q24 | C/A | 0.39 | 3888 | 1.05 (0.55, 1.54) | 3.4 × 10−5 | 14 405 | −0.19 (−0.47, 0.09) | 0.18 |

| rs10893006 | 11 | 11q24 | T/C | 0.34 | 3849 | 0.92 (0.41, 1.43) | 4.5 × 10−4 | 14 413 | −0.20 (−0.49, 0.08) | 0.17 |

| rs17510813 | 14 | SRP54/FAM177A1 | T/C | 0.12 | 3893 | −1.31 (−2.08, −0.55) | 7.0 × 10−4 | |||

| rs17595975 | 14 | SRP54/FAM177A1 | T/G | 0.11 | 3873 | −1.28 (−2.09, −0.48) | 1.7 × 10−3 | 14 115 | −0.03 (−0.48, 0.41) | 0.88 |

| rs857252 | 20 | UBOX5/FASTKD5 | G/T | 0.38 | 3891 | −1.09 (−1.61, −0.58) | 2.9 × 10−5 | 13 628 | −0.07 (−0.36, 0.21) | 0.62 |

| rs5759068 | 22 | 22q11 | T/C | 0.39 | 3872 | −1.19 (−1.70, −0.67) | 5.2 × 10−6 | 14 446 | −0.18 (−0.46, 0.10) | 0.20 |

aResults are ordered by chromosomal position. SNPs from the genome-wide analysis were selected for custom genotyping in independent samples only if P < 1 × 10−5 for associations with either LDL-C or ApoB response, or if P < 5 × 10−5 for both LDL-C and ApoB response.

bThe average proportional LDL-C reduction in response to simvastatin 40 mg daily was 42.36% and the average proportional reduction in ApoB was 32.76%.

Lipid response to statin in literature-based candidate genes

Custom genotyping data were available for 36 SNPs in literature-based candidate genes4,5,12,15,18–23 in up to 18 705 individuals. The study had 90% power to detect differences in the lipid response of <1% at P < 0.001 in SNPs with at least a 15% minor allele frequency (which is representative of the candidates selected). No significant associations were found for 26 of these SNPs (Supplementary material online, Tables S3 and S4). The results for the 10 SNPs at five loci that did reach statistical significance (P < 0.001) after correction for multiple testing are shown in Table 3. These five loci are discussed below (in order of the statistical significance for the proportional LDL-C or ApoB response).

Table 3.

Proportional lipid response associations (per allele) for literature-based candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms that were selected for custom genotyping and that reached statistical significance (P < 0.001)a

| SNP | Chr | Nearby gene(s)/locus | n | Effect/other allele | Effect allele freq | LDL-C response |

ApoB response |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional % reductionb (95% CI) | P-value | Additional % reductionb (95% CI) | P-value | ||||||

| rs646776 | 1 | CELSR2/PSRC1/SORT1 | 18 289 | C/T | 0.21 | 0.47 (0.13, 0.80) | 6.7 × 10−3 | 0.76 (0.47, 1.05) | 2.4 × 10−7 |

| rs3798220 | 6 | LPA | 14 472 | C/T | 0.02 | −2.30 (−3.47, −1.15) | 7.1 × 10−5 | −2.09 (−3.09, −1.11) | 2.5 × 10−5 |

| rs10455872 | 6 | LPA | 14 462 | G/A | 0.09 | −3.15 (−3.74, −2.58) | 8.1 × 10−28 | −2.86 (−3.35,−2.36) | 6.5 × 10−31 |

| rs2002042 | 10 | ABCC2 | 18 027 | T/C | 0.25 | 0.65 (0.33, 0.97) | 8.2 × 10−5 | 0.56 (0.28, 0.83) | 7.5 × 10−5 |

| rs11045819 | 12 | SLCO1B1 | 14 338 | A/C | 0.16 | 0.92 (0.49, 1.34) | 2.4 × 10−5 | 0.66 (0.29, 1.02) | 4.3 × 10−4 |

| rs4149056 | 12 | SLCO1B1 | 16 867 | C/T | 0.15 | −1.15 (−1.57, −0.74) | 5.0 × 10−8 | −0.96 (−1.31, −0.60) | 1.0 × 10−7 |

| rs4803750 | 19 | APOE Cluster | 18 326 | G/A | 0.07 | 1.22 (0.68, 1.74) | 8.5 × 10−6 | 1.21 (0.75, 1.66) | 2.6 × 10−7 |

| rs2075650 | 19 | APOE Cluster | 18 265 | G/A | 0.14 | −0.82 (−1.22, −0.41) | 7.8 × 10−5 | −0.77 (−1.12, −0.42) | 1.3 × 10−5 |

| rs7412 | 19 | APOE Cluster | 14 455 | T/C | 0.08 | 2.55 (1.98, 3.11) | 4.8 × 10−18 | 2.84 (2.35, 3.32) | 4.9 × 10−29 |

| rs4420638 | 19 | APOE Cluster | 14 388 | G/A | 0.18 | −0.96 (−1.38, −0.54) | 6.4 × 10−6 | −0.91 (−1.27, −0.55) | 5.7 × 10−7 |

aResults are ordered by chromosomal position. Results for all literature-based candidate SNPs selected for custom genotyping are shown in Supplementary material online, Table S3 and S4.

bThe average proportional LDL-C reduction in response to simvastatin 40 mg daily was 42.36% and the average proportional reduction in ApoB was 32.76%.

LPA locus

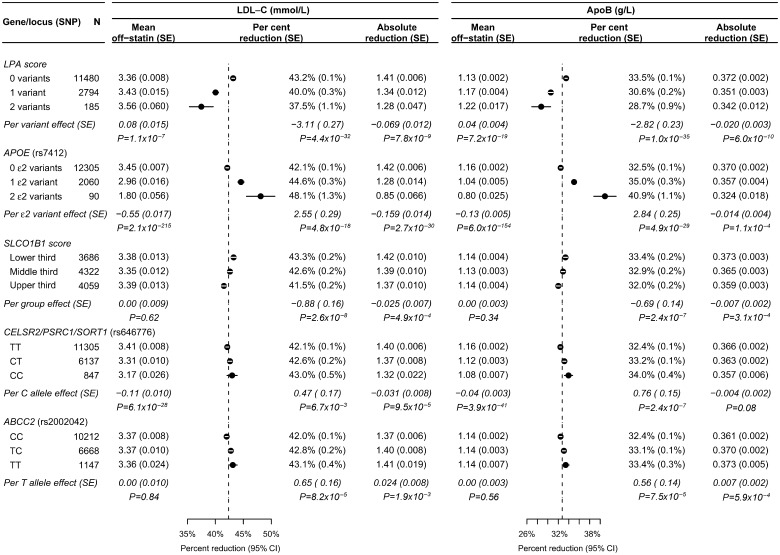

For two SNPs at the LPA locus, rs3798220 and rs10455872, there were 2.30% and 3.15% smaller proportional LDL-C reductions with statin therapy per minor allele and similar effects on the ApoB response (Table 3). These two LPA SNPs were independent (r2 = 0.02) and the sum of the minor alleles in the two SNPs was used to construct an LPA genotype score (as had been done previously for associations with coronary disease risk).27 Higher LPA genotype scores were associated with smaller proportional lipid reductions but higher off-statin lipid levels, and with slightly smaller absolute lipid reductions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Lipid and lipid response associations with literature-based candidate loci that were significantly associated (P < 0.001) with the proportional lipid response. Estimated effects and standard errors are shown. Per cent reductions and 95% confidence intervals by genotype are plotted and the average response in all genotyped participants is shown by a dashed line. The SLCO1B1 score was calculated by joint regression on rs4149056, rs11045819, rs12372157, and rs2306283. The regression coefficients (per additional effect allele) were 0.013, −0.018, 0.015, −0.010, respectively, for the proportional LDL cholesterol response, and 0.011, −0.010, 0.010, −0.008, respectively, for the proportional apolipoprotein B response.

APOE locus

Of the four genotyped SNPs in the APOE region, only rs7412 (the ε2 SNP) and rs4420638 (an approximate proxy for the rs429358 ε4 SNP; r2 ∼ 0.7)28,29 contributed independent information. The rs7412 T allele (ε2) was strongly associated with off-statin LDL-C levels, with a 0.55 mmol/L lower mean LDL-C per variant (Figure 3). Consequently, despite being associated with a 2.5% larger proportional reduction in LDL-C with statin therapy, it was also associated with smaller absolute reductions. In contrast, the rs4420638 G allele (ε4 proxy) was associated with a 0.16 mmol/L higher off-statin LDL-C, a 1% smaller proportional reduction, and a slightly larger absolute reduction (Table 3, Supplementary material online, Table S3).

SLCO1B1 locus

The rs11045819 and rs4149056 SNPs each showed 1% differences per allele in the proportional lipid reduction (Table 3), and rs12372157 and rs2306283 showed smaller effects (Supplementary material online, Tables S3 and S4). All four of these SNPs contributed independent information and SLCO1B1 genotype scores were calculated using the joint regression coefficients for the proportional LDL-C and ApoB responses. Higher scores were associated with smaller proportional lipid reductions per tertile (Figure 3) and, since the score was not associated with differences in off-statin lipid levels, higher scores were also associated with smaller absolute lipid reductions.

CELSR2/PSRC1/SORT1 locus

The rs646776 C allele was associated with a 0.47% larger proportional LDL-C reduction and 0.76% larger ApoB reduction (Figure 3). However, it was also strongly associated with lower off-statin lipid levels, and the net effect was smaller absolute reductions.

ABCC2 locus

The rs2002042 T allele was associated with a 0.65% larger proportional LDL-C reduction and 0.56% larger ApoB reduction and, since it was not associated with off-statin lipid levels, was associated with slightly larger absolute reductions in the lipid response.

Other literature-based candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms

Suggestive associations (unadjusted P< 0.01) with proportional lipid response were also seen with SNPs in APOA5/ZNF259, LIPC, ABCB1, PON1, and CETP (Supplementary material online, Tables S3–S5). In secondary analyses of the absolute lipid response, SNPs in or near LDLR, CETP, and LIPC were significantly associated (P < 0.001; Supplementary material online, Tables S3 and S4), and there were suggestive associations with SNPs in or near APOB and ABCB1 (P < 0.01; Supplementary material online, Table S5). These associations with an absolute lipid response corresponded to trends in off-statin lipid levels (Supplementary material online, Tables S3–S5). Other SNPs previously associated with the lipid response—such as rs10474433 (HMGCR), rs2231142 (ABCG2), rs9367897 (a direct proxy for rs6924995; MYLIP), and rs1627770 (ALG10)5,15,18,30 were not confirmed in the present study (Supplementary material online, Tables S3–S5).

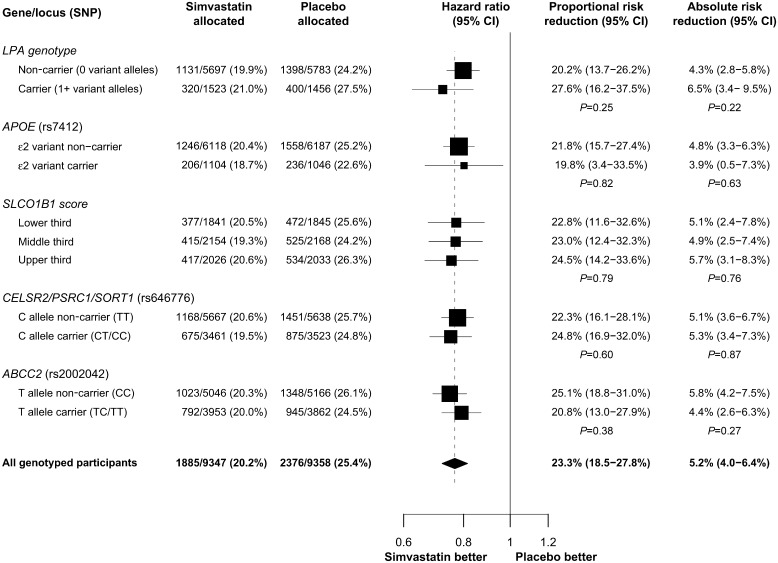

Vascular risk response to statin by genotype

On average during the 5-year randomized treatment period in the Heart Protection Study, there was a 1.0 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C between participants allocated 40 mg simvastatin daily vs. placebo.25 In the genotyped participants, random allocation to 40 mg simvastatin daily reduced the proportional 5-year risk of major vascular events by 23.3% (95% CI: 18.5–27.8%) and the absolute risk by 5.2% (95% CI: 4.0–6.4%; Figure 4). There were no statistically significant differences in either the proportional or the absolute reductions in major vascular events by genotype at any of the loci that were associated with proportional lipid response (Figure 4). However, some of these variants were associated with differences in the underlying risk of major vascular events (e.g. placebo group risk of 27.5% in LPA carriers vs. 24.2% in non-carriers) and with differences, albeit non-significant, in the absolute risk reductions (e.g. 6.5% in LPA carriers vs. 4.3% in non-carriers).

Figure 4.

Effects of simvastatin on major vascular events by genotype. Proportional and absolute risk reduction are shown by genotype for loci that were significantly associated with proportional lipid response (P < 0.001). Estimates are given with 95% confidence intervals and P-values are given for the trend across genotypes. Hazard ratios and 95% CIs are plotted with box sizes weighted by the inverse-variance of the estimate. The hazard ratio in all genotyped participants is shown by a dashed line.

Discussion

The present study identified associations with the lipid response to simvastatin for SNPs in three genes—LPA, CELSR2/PSRC1/SORT1, and ABCC2—that had not been reported previously. It also provided confirmation for independent SNP associations at the LPA, APOE, and SLCO1B1 loci that had previously been reported to be associated with the lipid response to other statins.5,15,18 The 10 variants associated with lipid response in the present study were in LDL-related genes, the LPA gene and statin pharmacokinetic genes, and all of them had small effects on the lipid response (0.5–3.0% per allele). Given these findings, it seems unlikely that there are common variants that alter the lipid response to statin therapy by more than a few per cent. This large randomized study also found no significant associations of these variants with the proportional or absolute risk reductions produced by simvastatin therapy, suggesting that the clinical relevance of these variants for guiding statin therapy may be limited.

LDL-related genes

Several genes (including APOE, CELSR2/PSRC1/SORT1, and LDLR) have previously been associated in genome-wide studies with moderately large effects on off-statin LDL-C levels (>0.1 mmol/L per allele).20 In the present study, some variants were found to be associated with small, but significant, differences in the proportional lipid response to statin therapy (<3% per allele compared with the overall 42% LDL-C reduction). In each case, the variant was also associated with differences in off-statin LDL-C levels, such that some of the variants produced larger proportional lipid responses. A number of studies have reported effects of these and other LDL-related genes (including APOE, LDLR, HMGCR, and PCSK9) on the lipid response to statins.4–6,8,9,12–16,18 However, some of those studies described the effects only after adjustment for the off-statin LDL-C level (without allowance for the effects of measurement error).8,9,12,15,16 Given the observed effects of these variants on off-statin LDL-C levels, such adjustments may account for between-study differences in the reported effects of statin therapy on the proportional lipid response.18,31 Some genes found to be associated with higher LDL-C levels (e.g. APOE) have been associated with higher risks of cardiovascular disease.20 Similarly, in the present study, the effects of these LDL-related genotypes on off-statin LDL-C levels were directionally consistent with their effects on absolute risk in the placebo arm. Large-scale meta-analyses of randomized trials have established that the reduction in the risk of major vascular events with statin therapy is related to the absolute reduction in LDL-C across a wide range of pre-treatment LDL-C levels.1 In the present randomized trial, despite the small differences in absolute risk and absolute LDL-C reduction associated with some of these variants, simvastatin therapy produced large and significant reductions in vascular risk irrespective of genotype (Figure 4).

LPA genotype

Levels of the LDL-like particle lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] are largely determined by the LPA gene.32 Previous studies have reported an association of rs10455872 in LPA with the lipid response to statin therapy,5,18 and the present study not only confirms it but has also identified an association with an independent SNP (rs3798220). Assays of LDL-C and ApoB typically include contributions from both LDL and Lp(a) particles, but statin therapy does not reduce the number or cholesterol content of Lp(a) particles.33 LPA variant carriers have higher Lp(a) levels and a greater proportion of their measured LDL-C resides in Lp(a) particles which is not amenable to the effects of statins. Hence, studies with direct measures of Lp(a) molar levels and Lp(a)-cholesterol content are needed to clarify the impact of LPA genotype on the lipid response to statin therapy. In the present large randomized trial, the proportional reductions in major vascular events with statin therapy were not significantly different between LPA carriers and non-carriers, and remained significant in all LPA genotype groups (Figure 4). The LPA genotype has previously been associated with cardiovascular risk,5,27 and LPA carriers in the present study were at a higher absolute risk of major vascular events than non-carriers. However, although the absolute reduction in risk with statin therapy appeared to be bigger among LPA carriers, this difference was also not statistically significant.

Statin pharmacokinetic genes

Several genes that have been implicated in pharmacokinetic pathways3 have been associated with small differences in the lipid response to statin therapy in both the present study (SLCO1B1 and ABCC2) and previous reports (e.g. SLCO1B1, ABCG2, and ABCB1).5,12,16 The SLCO1B1 rs4149056 variant is associated with a weaker lipid response to statin therapy, impaired hepatic uptake, higher blood levels of statins, and a substantially higher risk of myopathy.19 The increase in myopathy risk seen with this variant in patients on simvastatin makes knowledge of this genotype of potential value in guiding statin choice (especially if other risk factors for myopathy are present). In the present study, however, the SLCO1B1 and other gene variants involved in statin pharmacokinetics only had small effects (<1% per allele) on the lipid response to statin therapy and, even in combination, the four SLCO1B1 SNPs and one ABCC2 SNP only explained <0.5% of the variance in response. Consequently, their value for informing clinical decisions related to maximizing statin efficacy would seem to be limited.

Limitations

The present large study of the lipid response to simvastatin therapy was undertaken in a fully compliant population with individual-level response measurements. But, since only one off-statin and one on-statin lipid measurement was available for all of the participants, it was not possible to adjust the effects of genetic variants on the lipid response for off-statin lipid levels without introducing bias due to measurement error.18,31 Instead, the observed associations with off-statin lipid levels were considered in the interpretation of the results. These findings are broadly consistent with those from previously reported studies after taking into account differences in genotyping platforms (e.g. the variants that were measured), analytical approaches (in particular, adjustment for off-statin lipid levels) and chance.5,15,18 The present analyses had 90% power to detect common variants associated with differences of 2.5% in the LDL-C response (e.g. 42.5 vs. 40% reduction) in the genome-wide study and of 1% in the candidate gene study. With 4261 major vascular events among genotyped patients randomized between simvastatin vs. placebo for 5 years, this is the largest single study of the effects of genetic variants on the risk and lipid reductions produced by statin therapy. However, many more events (perhaps through collaborative meta-analyses of several trials) would be needed for genome-wide investigation of variation in the risk response to statins.

Conclusion

Common genetic variants do not appear to alter the lipid response to statin therapy by more than a few per cent. Statin therapy produces substantial proportional reductions in the risks of major vascular events, and these reductions were not found to be materially altered by genetic variants that influence lipid response. These findings support the current policy of basing decisions about the use of statin therapy, and its intensity, chiefly on an individual's estimated risk of having a major vascular event.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

The Heart Protection Study (ISRCTN48489393) was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation, Merck & Co (manufacturers of simvastatin), and Roche Vitamins Ltd (manufacturers of vitamins). Genotyping was supported by a grant to Oxford University and CNG from Merck & Co. J.C.H. acknowledges support from the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence, Oxford (RE/08/004). The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the data collection or analysis, or in the decision to submit the results for publication. The CTSU has a policy of not accepting honoraria or other payments from the pharmaceutical industry, except for reimbursement of costs to participate in scientific meetings.

Conflict of interest: The University of Oxford has been granted a patent for a genetic variant related to statin-induced myopathy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Heart Protection Study was designed and conducted by the Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU) at the University of Oxford. This genetic study of the lipid response to statin therapy was designed, analysed, and interpreted by the CTSU and genotyping was done by the Centre National de Génotypage (CNG), Evry. The most important acknowledgements are to the participants in the study, to the Steering Committee and to the collaborators.25 We also gratefully acknowledge the staff of the Wolfson laboratories in CTSU for their help with processing, storage and retrieval of blood samples.

References

- 1.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones P, Kafonek S, Laurora I, Hunninghake D. Comparative dose efficacy study of atorvastatin versus simvastatin, pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia (the CURVES study) Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:582–587. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00965-x. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00965-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangravite LM, Thorn CF, Krauss RM. Clinical implications of pharmacogenomics of statin treatment. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6:360–374. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500384. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber MJ, Mangravite LM, Hyde CL, Chasman DI, Smith JD, McCarty CA, Li X, Wilke RA, Rieder MJ, Williams PT, Ridker PM, Chatterjee A, Rotter JI, Nickerson DA, Stephens M, Krauss RM. Genome-wide association of lipid-lowering response to statins in combined study populations. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009763. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chasman DI, Giulianini F, Macfadyen J, Barratt BJ, Nyberg F, Ridker PM. Genetic determinants of statin-induced low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction: the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:257–264. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961144. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chasman DI, Posada D, Subrahmanyan L, Cook NR, Stanton VP, Jr, Ridker PM. Pharmacogenetic study of statin therapy and cholesterol reduction. JAMA. 2004;291:2821–2827. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2821. doi:10.1001/jama.291.23.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couvert P, Giral P, Dejager S, Gu J, Huby T, Chapman MJ, Bruckert E, Carrie A. Association between a frequent allele of the gene encoding OATP1B1 and enhanced LDL-lowering response to fluvastatin therapy. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1217–1227. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.9.1217. doi:10.2217/14622416.9.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly LA, Doney AS, Dannfald J, Whitley AL, Lang CC, Morris AD, Donnan PT, Palmer CN. A paucimorphic variant in the HMG-CoA reductase gene is associated with lipid-lowering response to statin treatment in diabetes: a GoDARTS study. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18:1021–1026. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283106071. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283106071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly LA, Palmer CN, Whitley AL, Lang CC, Doney AS, Morris AD, Donnan PT. Apolipoprotein E genotypes are associated with lipid-lowering responses to statin treatment in diabetes: a Go-DARTS study. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18:279–287. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f60aad. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f60aad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerola T, Lehtimaki T, Kahonen M, Nieminen T. Statin pharmacogenomics: lipid response and cardiovascular outcomes. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2010;4:150–158. doi:10.1007/s12170-010-0081-0. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangravite LM, Krauss RM. Pharmacogenomics of statin response. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:409–414. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328235a5a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mega JL, Morrow DA, Brown A, Cannon CP, Sabatine MS. Identification of genetic variants associated with response to statin therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1310–1315. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.188474. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.188474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polisecki E, Muallem H, Maeda N, Peter I, Robertson M, McMahon AD, Ford I, Packard C, Shepherd J, Jukema JW, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Buckley BM, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. Genetic variation at the LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase gene loci, lipid levels, statin response, and cardiovascular disease incidence in PROSPER. Atherosclerosis. 2008;200:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polisecki E, Peter I, Robertson M, McMahon AD, Ford I, Packard C, Shepherd J, Jukema JW, Blauw GJ, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Trompet S, Buckley BM, Murphy MB, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. Genetic variation at the PCSK9 locus moderately lowers low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, but does not significantly lower vascular disease risk in an elderly population. Atherosclerosis. 2008;200:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.005. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson JF, Hyde CL, Wood LS, Paciga SA, Hinds DA, Cox DR, Hovingh GK, Kastelein JJ. Comprehensive whole-genome and candidate gene analysis for response to statin therapy in the Treating to New Targets (TNT) cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:173–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.818062. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.818062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson JF, Man M, Johnson KJ, Wood LS, Lira ME, Lloyd DB, Banerjee P, Milos PM, Myrand SP, Paulauskis J, Milad MA, Sasiela WJ. An association study of 43 SNPs in 16 candidate genes with atorvastatin response. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:352–358. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500328. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zintzaras E, Kitsios GD, Triposkiadis F, Lau J, Raman G. APOE gene polymorphisms and response to statin therapy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009;9:248–257. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.25. doi:10.1038/tpj.2009.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deshmukh HA, Colhoun HM, Johnson T, McKeigue PM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, Fuller JH, Livingstone S, Charlton-Menys V, Neil A, Poulter N, Sever P, Shields DC, Stanton AV, Chatterjee A, Hyde C, Calle RA, Demicco DA, Trompet S, Postmus I, Ford I, Jukema JW, Caulfield M, Hitman GA. Genome-wide association study of genetic determinants of LDL-c response to atorvastatin therapy: importance of Lp(a) J Lipid Res. 2012;53:1000–1011. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P021113. doi:10.1194/jlr.P021113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SEARCH Collaborative Group. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy—a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:789–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, Pirruccello JP, Ripatti S, Chasman DI, Willer CJ, Johansen CT, Fouchier SW, Isaacs A, Peloso GM, Barbalic M, Ricketts SL, Bis JC, Aulchenko YS, Thorleifsson G, Feitosa MF, Chambers J, Orho-Melander M, Melander O, Johnson T, Li X, Guo X, Li M, Shin Cho Y, Jin Go M, Jin Kim Y, Lee JY, Park T, Kim K, Sim X, Twee-Hee Ong R, Croteau-Chonka DC, Lange LA, Smith JD, Song K, Hua Zhao J, Yuan X, Luan J, Lamina C, Ziegler A, Zhang W, Zee RY, Wright AF, Witteman JC, Wilson JF, Willemsen G, Wichmann HE, Whitfield JB, Waterworth DM, Wareham NJ, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Voight BF, Vitart V, Uitterlinden AG, Uda M, Tuomilehto J, Thompson JR, Tanaka T, Surakka I, Stringham HM, Spector TD, Soranzo N, Smit JH, Sinisalo J, Silander K, Sijbrands EJ, Scuteri A, Scott J, Schlessinger D, Sanna S, Salomaa V, Saharinen J, Sabatti C, Ruokonen A, Rudan I, Rose LM, Roberts R, Rieder M, Psaty BM, Pramstaller PP, Pichler I, Perola M, Penninx BW, Pedersen NL, Pattaro C, Parker AN, Pare G, Oostra BA, O'Donnell CJ, Nieminen MS, Nickerson DA, Montgomery GW, Meitinger T, McPherson R, McCarthy MI, McArdle W, Masson D, Martin NG, Marroni F, Mangino M, Magnusson PK, Lucas G, Luben R, Loos RJ, Lokki ML, Lettre G, Langenberg C, Launer LJ, Lakatta EG, Laaksonen R, Kyvik KO, Kronenberg F, Konig IR, Khaw KT, Kaprio J, Kaplan LM, Johansson A, Jarvelin MR, Janssens AC, Ingelsson E, Igl W, Kees Hovingh G, Hottenga JJ, Hofman A, Hicks AA, Hengstenberg C, Heid IM, Hayward C, Havulinna AS, Hastie ND, Harris TB, Haritunians T, Hall AS, Gyllensten U, Guiducci C, Groop LC, Gonzalez E, Gieger C, Freimer NB, Ferrucci L, Erdmann J, Elliott P, Ejebe KG, Doring A, Dominiczak AF, Demissie S, Deloukas P, de Geus EJ, de Faire U, Crawford G, Collins FS, Chen YD, Caulfield MJ, Campbell H, Burtt NP, Bonnycastle LL, Boomsma DI, Boekholdt SM, Bergman RN, Barroso I, Bandinelli S, Ballantyne CM, Assimes TL, Quertermous T, Altshuler D, Seielstad M, Wong TY, Tai ES, Feranil AB, Kuzawa CW, Adair LS, Taylor HA, Jr, Borecki IB, Gabriel SB, Wilson JG, Holm H, Thorsteinsdottir U, Gudnason V, Krauss RM, Mohlke KL, Ordovas JM, Munroe PB, Kooner JS, Tall AR, Hegele RA, Kastelein JJ, Schadt EE, Rotter JI, Boerwinkle E, Strachan DP, Mooser V, Stefansson K, Reilly MP, Samani NJ, Schunkert H, Cupples LA, Sandhu MS, Ridker PM, Rader DJ, van Duijn CM, Peltonen L, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M, Kathiresan S. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. doi:10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link E. Oxford: University of Oxford; 2009. Genome-wide association of statin-induced myopathy (PhD thesis) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coronary Artery Disease (C4D) Genetics Consortium. A genome-wide association study in Europeans and South Asians identifies five new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:339–344. doi: 10.1038/ng.782. doi:10.1038/ng.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S, Reilly MP, Assimes TL, Holm H, Preuss M, Stewart AFR, Barbalic M, Gieger C, Absher D, Aherrahrou Z, Allayee H, Altshuler D, Anand SS, Andersen K, Anderson JL, Ardissino D, Ball SG, Balmforth AJ, Barnes TA, Becker DM, Becker LC, Berger K, Bis JC, Boekholdt SM, Boerwinkle E, Braund PS, Brown MJ, Burnett MS, Buysschaert I, Carlquist JF, Chen L, Cichon S, Codd V, Davies RW, Dedoussis G, Dehghan A, Demissie S, Devaney JM, Diemert P, Do R, Doering A, Eifert S, Mokhtari NEE, Ellis SG, Elosua R, Engert JC, Epstein SE, de Faire U, Fischer M, Folsom AR, Freyer J, Gigante B, Girelli D, Gretarsdottir S, Gudnason V, Gulcher JR, Halperin E, Hammond N, Hazen SL, Hofman A, Horne BD, Illig T, Iribarren C, Jones GT, Jukema JW, Kaiser MA, Kaplan LM, Kastelein JJP, Khaw K-T, Knowles JW, Kolovou G, Kong A, Laaksonen R, Lambrechts D, Leander K, Lettre G, Li M, Lieb W, Loley C, Lotery AJ, Mannucci PM, Maouche S, Martinelli N, McKeown PP, Meisinger C, Meitinger T, Melander O, Merlini PA, Mooser V, Morgan T, Muhleisen TW, Muhlestein JB, Munzel T, Musunuru K, Nahrstaedt J, Nelson CP, Nothen MM, Olivieri O, Patel RS, Patterson CC, Peters A, Peyvandi F, Qu L, Quyyumi AA, Rader DJ, Rallidis LS, Rice C, Rosendaal FR, Rubin D, Salomaa V, Sampietro ML, Sandhu MS, Schadt E, Schafer A, Schillert A, Schreiber S, Schrezenmeir J, Schwartz SM, Siscovick DS, Sivananthan M, Sivapalaratnam S, Smith A, Smith TB, Snoep JD, Soranzo N, Spertus JA, Stark K, Stirrups K, Stoll M, Tang WHW, Tennstedt S, Thorgeirsson G, Thorleifsson G, Tomaszewski M, Uitterlinden AG, van Rij AM, Voight BF, Wareham NJ, Wells GA, Wichmann HE, Wild PS, Willenborg C, Witteman JCM, Wright BJ, Ye S, Zeller T, Ziegler A, Cambien F, Goodall AH, Cupples LA, Quertermous T, Marz W, Hengstenberg C, Blankenberg S, Ouwehand WH, Hall AS, Deloukas P, Thompson JR, Stefansson K, Roberts R, Thorsteinsdottir U, O'Donnell CJ, McPherson R, Erdmann J. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–338. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. doi:10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering therapy and of antioxidant vitamin supplementation in a wide range of patients at increased risk of coronary heart disease death: early safety and efficacy experience. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:725–741. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1350. doi:10.1053/euhj.1998.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.GLIDERS. Genome-wide LInkage DisEquilibrium Repository and Search engine. http://mather.well.ox.ac.uk/GLIDERS/ accessed 4 August 2011.

- 27.Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, Kyriakou T, Goel A, Heath SC, Parish S, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, Rust S, Bennett D, Silveira A, Malarstig A, Green FR, Lathrop M, Gigante B, Leander K, de Faire U, Seedorf U, Hamsten A, Collins R, Watkins H, Farrall M. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ken-Dror G, Talmud PJ, Humphries SE, Drenos F. APOE/C1/C4/C2 gene cluster genotypes, haplotypes and lipid levels in prospective coronary heart disease risk among UK healthy men. Mol Med. 2010;16:389–399. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McPherson R. A gene-centric approach to elucidating cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:3–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.848986. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.848986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomlinson B, Hu M, Lee VW, Lui SS, Chu TT, Poon EW, Ko GT, Baum L, Tam LS, Li EK. ABCG2 polymorphism is associated with the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol response to rosuvastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:558–562. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.232. doi:10.1038/clpt.2009.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanez ND, Kronmal RA, Shemanski LR. The effects of measurement error in response variables and tests of association of explanatory variables in change models. Stat Med. 1998;17:2597–2606. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981130)17:22<2597::aid-sim940>3.0.co;2-g. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981130)17:222597::AID-SIM9403.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berglund L, Ramakrishnan R. Lipoprotein(a): an elusive cardiovascular risk factor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2219–2226. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000144010.55563.63. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000144010.55563.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scanu AM, Hinman J. Issues concerning the monitoring of statin therapy in hypercholesterolemic subjects with high plasma lipoprotein(a) levels. Lipids. 2002;37:439–444. doi: 10.1007/s11745-002-0915-1. doi:10.1007/s11745-002-0915-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.