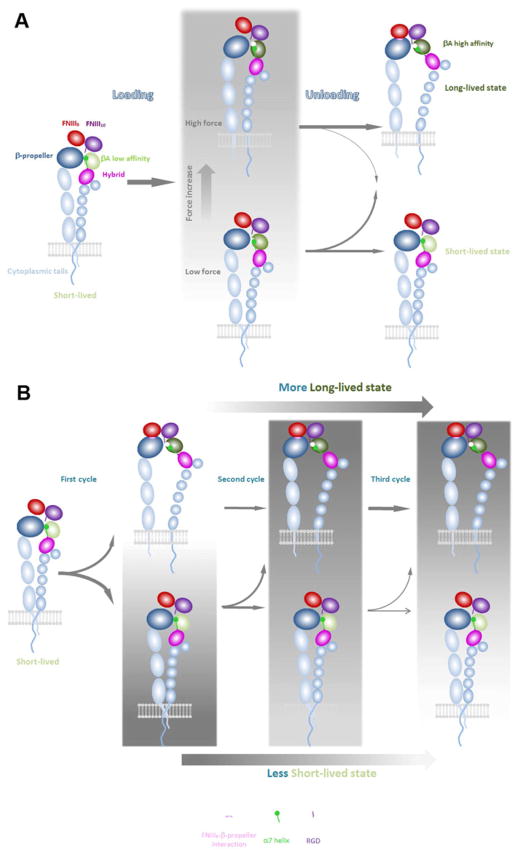

Figure 7. Model of cyclic mechanical reinforcement.

A, Reinforcing FN–α5β1 bond by a single-cycled force. Left: Liganded integrin in the short-lived state. Key α5β1 domains are indicated along with the RGD and synergy binding sites on the FNIII 10 and 9 domains, respectively. Middle: Force applied via the ligand primes the integrin for conformational change in the headpiece. Higher peak force (Top) better primes the integrin than lower peak force (Bottom). Right: During unloading, the FN–α5β1 bond may be switched to the long-lived state (Top) or may return to the short-lived state (Bottom). A bond previously primed by a higher peak force is more likely to be switched to the long lived state than a bond primed by a lower peak force, as indicated by the sizes of the arrows. B, Reinforcing FN–α5β1 bond by multi-cycled small forces. Far-left: FN bound α5β1 in the short-lived state as that in A Left. Mid-left: A loading-unloading cycle has a certain probability to switch the FN–α5β1 bond to the long-lived state (Top) but also a probability not to change the short-lived state (Bottom). Mid-right: After another loading-unloading cycle, the bond that is already in the long-lived state stays in the long-lived state (Top). However, the bond that remains in the short-lived state has a certain probability to switch to the long-lived state (Bottom). Far-right: As the number of cycles increases, the FN–α5β1 bond is more and more likely to be switched to the long-lived state (Top) and less and less likely to remain in the short-lived state (Bottom), resulting in an accumulating effect.