Abstract

Chloroquine retinopathy is a known complication of long-term use of chloroquine. This retinopathy can appear even after usage of chloroquine has stopped. The present case report describes the history and clinical features of chloroquine retinopathy developing a decade after discontinuing the drug.

Keywords: Chloroquine Retinopathy, Delayed Onset, Drug

INTRODUCTION

Chloroquine has been in use for many years for the treatment of malaria and for the long term prophylaxis of inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematous, and Sjogren’s syndrome.1 For the latter indications chloroquine was previously prescribed in dosages of 400–600 mg/day but has now been reduced to 250 mg/day.2,3

Ocular toxicity associated with chloroquine has been extensively studied since its description in 1957 by Cambaiaggi4 and in 1959 by Hobbs.5 It can lead to corneal deposits, lens opacities, and maculopathy causing bull’s eye lesion.6,7 Chloroquine retinopathy (CR) is a severe form of retinal toxicity caused by long-term use of chloroquine with an incidence of 1–16%.8,9 Retinal photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium have been postulated as the primary sites of involvement in chloroquine retinopathy.9 Once established, CR is irreversible and may progress even after cessation of the drug.9

In this case report, we present the history and clinical findings of a patient with late onset ocular toxicity, 10 years after stopping chloroquine treatment.

CASE REPORT

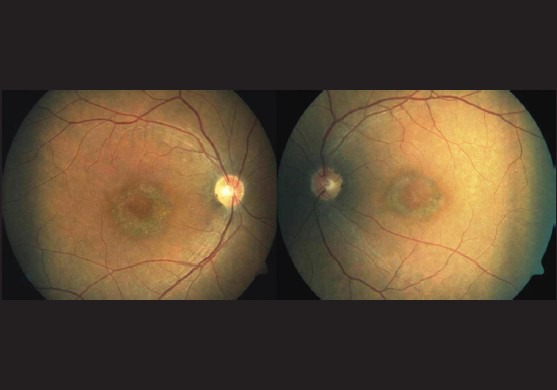

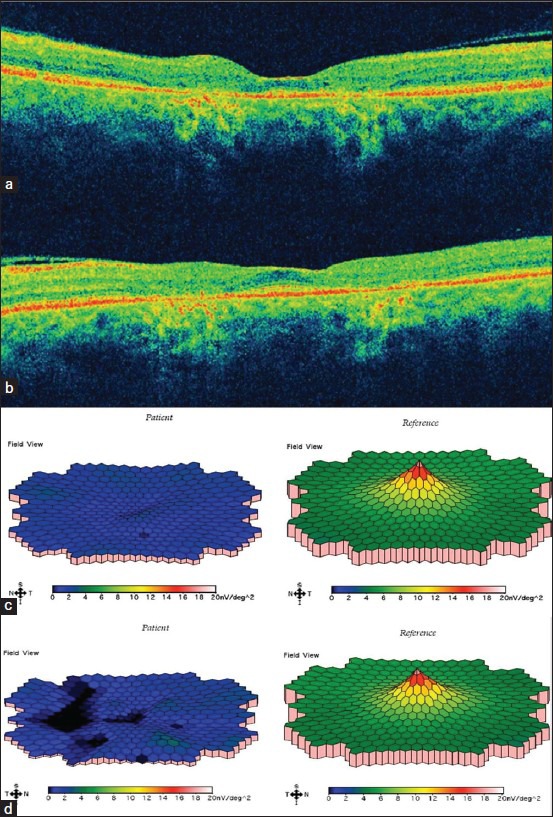

A 52-year-old female with Sjogren’s syndrome presented to us with diminution of vision in both eyes for 1 year. She was diagnosed 19 years prior to presentation and had been taking chloroquine (250 mg daily) for 7 years. Later, the medication was changed to methotrexate (10 mg/week). The best corrected visual acuities using a Snellen chart were 6/9, N6 and 6/6, N6 in the right and left eye respectively. She could identify 1 plate correctly in the right eye and 10 plates in the left eye using Ishihara’s isochromatic plates. Anterior segment examination was within normal limits in both eyes. Indirect ophthalmoscopy of both eyes showed normal looking central fovea with a circular ring shaped area of depigmentation measuring approximately two disk diameters in size akin to a “Bull’s eye appearance”. The rest of the retina and the optic nerve head were within normal limits. Fundus fluorescein angiography showed increased hyperfluorescence due to a window defect in the macular area corresponding to the area of depigmentation and reduced hyperfluorescence due to blockage of choroidal fluorescence in the central fovea [Figures 1 and 2]. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography of both eyes showed reduced central foveal thickness (right eye 108 μ and left eye 132 μ). Both eyes showed generalized loss of outer retinal layers in foveal and parafoveal areas while the left eye showed preservation of the inner segment outer segment (IS- OS) junction [Figures 3a and b]. Full-field electroretinogram revealed normal photopic and scotopic responses for both eyes. Multifocal electroretinogram showed reduced central and paracentral ring responses and reduced perifoveal ring responses in both eyes [Figures 3c and d]. Based on the history and clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with late onset chloroquine retinopathy. The patient was informed about the condition and a letter of recommendation addressed to her physician was sent documenting the importance of avoiding chloroquine.

Figure 1.

Color fundus photograph showing “bulls eye maculopathy”

Figure 2.

Fundus fluorescein angiogram showing a ring of increased hyperfluorescence (window defect) surrounding a central area of reduced hyperfluorescence (blocked fluorescence)

Figure 3.

(a) and (b) Optical coherence tomography showing generalized loss of outer retinal layers in parafoveal region in both eyes. (c) and (d) Multifocal electroretinogram showing reduced perifoveal ring responses in both eyes

DISCUSSION

In the present case, the patient had placed on chloroquine on a long-term basis over 10 years prior to presentation and had been under the care of an ophthalmologist thereafter. Her previous records did not reveal any finding suggestive of retinopathy. The onset of chloroquine retinopathy more than a decade after stopping chloroquine emphasizes the need for regular follow-up of patients with a history of long-term chloroquine usage.

Chloroquine is stored in tissues such as the liver and especially the pigmented uveal ocular tissue.10 Urinary excretion of chloroquine continues years after cessation of chloroquine.10 These findings buttress the diagnosis of late onset chloroquine retinopathy in our patient.

Currently there is no definite treatment for chloroquine retinopathy; hence, it is advisable to discontinue the drug as soon as the signs of toxicity are noted. According to the revised guidelines of the American Academy Of Ophthalmology, each patient who may be placed on long-term chloroquine should undergo a baseline ophthalmic examination which should include both subjective (10–2 visual field testing) and objective tests (autofluorescence, multifocal electroretinogram, and spectral domain optical coherence tomography).2 These tests should be repeated annually if the patient falls in the high risk category for developing chloroquine retinopathy.2

The present case report reiterates the need for regular follow-up of patients who have been on chloroquine, even after discontinuation of the treatment. This is important both for the ophthalmologist and the physician to educate the patient about the delayed presentation of this disease entity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tehrani R, Ostrowski RA, Hariman R, Jay WM. Ocular toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008;23:201–9. doi: 10.1080/08820530802049962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TY, Lyons JS, Mieler WF. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Revised recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxylchloroquine retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed H, Karlinsky W. Delayed onset of chloroquine retinopathy. Can Med Assoc J. 1967;97:1408–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cambiaggi A. Unusual ocular lesions in acase of systemic lupus erythromatosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1957;57:451–3. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1957.00930050463019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobbs H, Sorsby A, Freedman A. Retinopathy following chloroquine therapy. Lancet. 1959;2:478–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(59)90604-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein HN. Ophthalmologic considerations and testing in patients receiving long term antimalarial therapy. Am J Med. 1983;75:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nylander U. Ocular changes in chloroquine therapy. Acta Ophthalmol. 1967;92(Suppl):1–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertagnolio S, Tacconelli E, Camilli G, Tumbarelle M. Case report: Retinopathy after malaria prophylaxis with chloroquine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:637–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sassani J, Brucker AJ, Cobbs W. Progressive chloroquine retinopathy. Ann Ophthalmol. 1983;15:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zvaifler NJ, Rubin M, Bernstein H. Chloroquine osition. Arthritis Rheum. 1963;6:799. [Google Scholar]