Abstract

In this paper, we report a light driven, non-invasive cell membrane perforation technique based on the localized field amplification by a nanosecond pulsed laser near gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). The optoporation phenomena is investigated with pulses generated by a Nd:YAG laser for two wavelengths that are either in the visible (532 nm) or near infrared (NIR) (1064 nm). Here, the main objective is to compare on and off localized surface plasmonic resonance (LSPR) to introduce foreign material through the cell membrane using nanosecond laser pulses. The membrane permeability of human melanoma cells (MW278) has been successfully increased as shown by the intake of a fluorescent dye upon irradiation. The viability of this laser driven perforation method is evaluated by propidium iodide exclusion as well as MTT assay. Our results show that up to 25% of the cells are perforated with 532 nm pulses at 50 mJ/cm2 and around 30% of the cells are perforated with 1064 nm pulses at 1 J/cm2. With 532 nm pulses, the viability 2 h after treatment is 64% but it increases to 88% 72 h later. On the other hand, the irradiation with 1064 nm pulses leads to an improved 2 h viability of 81% and reaches 98% after 72 h. Scanning electron microscopy images show that the 5 pulses delivered during treatment induce changes in the AuNPs size distribution when irradiated by a 532 nm beam, while this distribution is barely affected when 1064 nm is used.

OCIS codes: (170.0170) Medical optics and biotechnology; (140.3538) Lasers, pulsed

1. Introduction

The membrane of eukaryote cell acts as a selective barrier between the cytoplasm and the extracellular space [1]. Only small ions and molecules as well as some organic molecules may penetrate through the cell membrane. Large molecules such as synthetic pharmaceutical drugs or DNA plasmids cannot be introduced into cells easily without damaging cell integrity. Many research areas such as gene therapy as well as therapeutical research would greatly benefit from tools that efficiently allow internalization of such molecules into cells [2–5]. Viral vector is currently the method mostly used to introduce foreign material into cells but safety and immunogenicity concerns [6,7] favored the development of alternative techniques to accomplish this task [2,8]. The main physical methods that have been developed include electroporation [9,10], direct injection [11] and laser methods such as laser induced stress wave [12,13], direct optoporation [14,15] and selective cell optoporation using light absorbing particles [16–19]. These methods however face major drawbacks. Electroporation may for instance yield low viability through irreversible electroporation [20,21] while direct injection and direct optoporation treat one cell at a time leading to a very low throughput.

Using AuNPs, our research group has recently introduced a new high throughput technique for permeabilizing human cancer cells [17]. In this approach AuNPs are deposited on cell membranes and irradiated by weakly focused femtosecond (fs) laser pulses, resulting in a significant increase of membrane permeability. Because of its low side effects and high selectivity, this new promising technique is a very efficient, high throughput and virus-free method that has the potential for transfection and has wide applications in both in vivo and the clinic. The AuNPs have several unique characteristics that make them the best option for cell membrane optoporation, drug delivery [22–24] and laser activated nano thermolysis [25–27] purposes. This uniqueness is due to the existence of a tunable localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) described as a collective and coherent oscillation of free electrons at the surface of nanoparticles in resonance with an electromagnetic (EM) wave light of a specific wavelength [28,29]. The plasmon resonance results in an intense absorption and scattering of incident light, as well as highly localized field enhancement at the plasmon resonance wavelength. Other spectacular characteristics of AuNPs are the presence of a significant surface functionalization capability to conjugate biomolecules and other targeting moieties [24,30,31] as well as oxidation resistance, which maximizes their biocompatibility [24]. In the technique described above, under irradiation, the AuNPs locally amplify the EM field which passes beyond the optical breakdown threshold and then leads to the formation of a cavitation bubble of submicron size. This bubble creates a nanometric pore on the cell membrane or simply disrupts the lipid membrane and increases permeability to allow the introduction of extracellular cargo [19]. While this technique presents numerous advantages, it uses a femtosecond laser that occupies a large area, is complicated to operate and has heavy costs. In order to increase its accessibility and decrease its cost, we adapted the process to a Nd:YAG nanosecond pulsed laser.

Other groups have exploited the plasmon resonance excited by nanosecond laser for the same purpose: Lin et al. [16] were amongst the first to demonstrate the permeability increase of cell membrane with plasmonic particles in 2003. The Lapotko group used it to create plasmonic nanobubbles that selectively kill cancer cells [25,27] and to transfect single J32 cell with a GFP plasmid [32]. Yao et al. have studied the influence of the laser parameters on the membrane permeability [18,33]. However, all these studies have been realized at a wavelength of 532 nm which is near the LSPR peak of spherical AuNPs. In this paper, we demonstrate the possibility of cell optoporation when the nanosecond pulsed laser wavelength is off resonance at near infrared (NIR) regime (1064 nm). The advantage of this approach is that when irradiated by NIR radiation, biological tissues present a low absorption coefficient as well as a low scattering coefficient thus minimizing the heat transferred by the EM wave to the cells. In addition, this approach maximizes the penetration depth thus opening the possibility to reach sub layer cells on in vivo specimens. Bashkatov et al. [34] has measured that the penetration depth in human skin is 0.9 mm at 532 nm while it is 3.3 mm at 1064 nm.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Laser setup

Laser irradiation was performed with a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (Brilliant B, Quantel, France) delivering pulses of 15 ns (for 532 nm) and 75 ns (for 1064 nm) at a repetition rate of 10 Hz. The 1 cm diameter beam is directed to the sample where a 150 mm focusing lens (Thorlabs, Newton, New Jersey) fixed on a micrometric stage allows adjusting the beam diameter to 1.6 mm at the sample plane. The petri dish is scanned at a speed of 3 mm/s with 1.1 mm step between lines by two micrometric translation stages (Thorlabs, Newton, New Jersey) controlled by computer. The irradiation is made on 3 regions of interest (5 x 5 mm2) in the petri dish and each region takes 90 seconds to irradiate, enabling the treatment of a large number of cells in very short time.

2.2. Cell preparation

Human melanoma cells (MW278) are routinely cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, L-glutamine and antibiotics (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON) in a 37 °C humidified incubator (5% CO2, 95% air). Prior to experiment, the cells are plated on a glass bottom culture dish (MaTek Corporation, Ashland, MA) to obtain a cell density of 70-80% at irradiation time. 100 nm gold nanoparticles (Nanopartz, CO, USA) are deposited on the cells to a final concentration of 8.3 μg/mL and they are incubated for a period of 4 hours. Before irradiation, the cells are washed with PBS to remove NPs that did not attach to the cell membrane. The extracellular cargo to be inserted in the cells is then mixed to the cell medium. For permeability measurements we added a small fluorophore, Lucifer yellow (LY, Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario), to a concentration of 0.3 mM. LY was not added in medium for MTT assays and SEM experiments.

2.3. Fluorescence microscopy

Two hours after treatment, cells are treated with Propidium Iodide solution (PI, Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario) at concentration of 1.5 μM to allow the identification of damaged cells with perforated membranes. They are then washed with PBS and fixed with 3.6% formaldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario). After another PBS washing, cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario) at 1 μM. An observer Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Toronto, Ontario) is used to take picture with a 10X objective. Each 5 X 5 mm2 zone is covered with 4–5 photos of each fluorescent channel and 3 control images (out of irradiated zones) are taken. Statistics are then calculated with a minimum of 3 different zones per fluence.

2.4. MTT assay

The cells are seeded in 12 well plates 24 h before the experiment. After irradiation, 150 μL of MTT solution (3 mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario) is mixed to each well. Plates are then protected from external light with an aluminum foil and placed at 37°C, 5% CO2 for another 3 h. Afterward, the medium is replaced with 0.5 mL of solubilization solution (0.1 N HCL in isopropanol) and the plate is weakly shaken for 5 min. The plate is then read with an Epoch microplate reader (Biotek instruments, Vermont, USA) in absorption mode at 570 nm with a reference at 690 nm.

2.5. Analysis

Fluorescent cells of each color are counted with the Image pro plus program (Media cybernetics, Washington, USA). A mean fluorescence background is calculated for the LY and PI fluorescence channel from the 3 control images in each petri dish and the detection threshold is set at the mean plus one standard deviation. Since many cells detach from the petri dish during irradiation, an adjustment is made by comparing the number of cells in the control image and the ones in irradiated zones. The viability is calculated as follow: [1 – (NPI + Nadjust)/(NDAPI + Nadjust)] * 100% and the perforation rate: NLY/(NDAPI + Nadjust) * 100%. The standard deviation is then calculated from all the images of a same fluence.

2.6. SEM

After the treatment, the cells are washed with PBS and 30 min later they are fixed with a 5% glutaraldehyde solution during 1 h. They are then washed with distilled water and dried under a laminar hood overnight. The next day, they are coated with a 5 nm gold layer and observed with a Quanta 200 SEM (FEI, Oregon, USA) in high vacuum mode.

3. Results

3.1. Perforation & viability

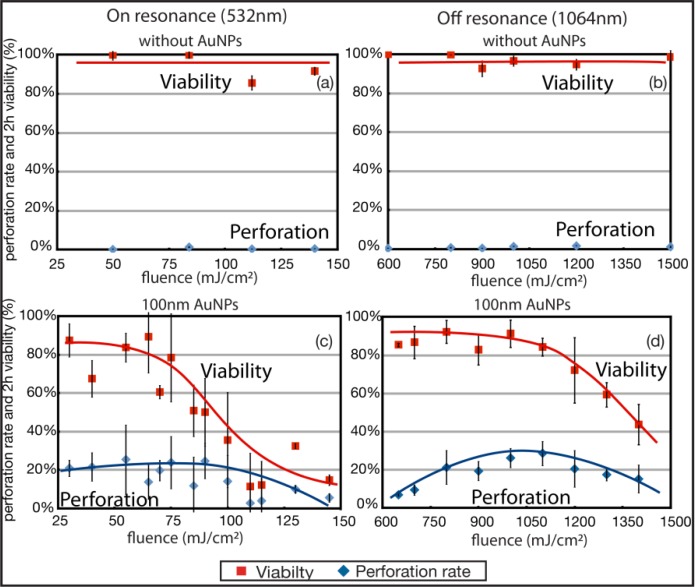

Human melanoma cells are grown to a density of 70-80% confluence on glass bottom petri dishes. First, the effect of the laser on cells without NPs was verified. Figures 1a and 1b show the constant viability (above 95%) for 532 nm and 1064 nm pulses over the fluence ranges of interest. The perforation rate is lower than 3% for each wavelength.

Fig. 1.

Permeabilization rate measured by LY introduction in melanoma cells and 2 h viability (by PI exclusion) in the operating range of fluence for 532 nm and 1064 nm wavelengths. (a) and (b) are cells irradiated without AuNPs while (c) and (d) represent cells with 100 nm AuNPs (n = 3 or 4, the error bars represent the standard deviation).

Prior to irradiation, cells are incubated for 4 h with 100 nm diameter AuNPs. Afterward, the cells are washed with PBS and the attached NPs are found near the cell membrane either as small cluster or individually. LY fluorophore is added to the cell solution and the cells are placed on the translation table. The laser is defocused to a spot of 1.6 mm in diameter and each 5 X 5 mm2 zone are scanned under the laser at the speed of 3 mm/s with a line to line step of 1.1 mm. The laser operates at 10 Hz and, every cell receives approximately 5 laser pulses (neglecting the overlaps in the line to line step). This scanning technique enables a large number of cells to be treated in a very short time lapse. Thus, the irradiation time of a 25 mm2 takes 2 minutes while the irradiation of a complete petri dish of 314 mm2 takes 8 minutes.

To determine the optimal fluences and to demonstrate the membrane perforation, we studied the LY intake efficacy as a function of the applied fluence, defined as the energy delivered per unit area (mJ/cm2). Cells alone irradiated with the laser at 532 or 1064 nm are impermeable to LY. The same scenario applies to cells loaded with NPs but not irradiated. A fluorescence background from untreated cell is determined for each petri and only treated cells that shows fluorescence above one standard deviation (calculated from the 3 control images) from this threshold are considered successfully perforated.

Irradiation with 532 nm pulses did not require high laser energy since 532 nm is in the absorption peak of 100 nm spherical nanoparticles. Fluences from 25 to 70 mJ/cm2 were enough to perforate and enable LY intake in more than 20% of the total irradiated cells while maintaining a viability between 65% and 85%. Above 100 mJ/cm2, most of the cells either die by large membrane disruption or they detach from the irradiated zones. The detached cells are counted in the viability as described in section 2.5. The optimal fluence that kept 83 ± 8% of the cells alive while permeabilizing 26 ± 18% of them is situated at 55 mJ/cm2. These results give an energy threshold that could enable one to design an experiment aimed either at killing harmful cells or, alternatively, treating them with exogenous materials by controlling their membrane permeability. The threshold energy corresponding to a viability of 50% is located at 85 mJ/cm2.

Figure 1d shows the perforation rate and viability as a function of the delivered fluence for 1064 nm pulses. The viability remains around 85% up to 1050 mJ/cm2 and decreases to 44% at 1.4 J/cm2. The perforation rate increases from 6% at 650 mJ/cm2 to 29% at 1.1 J/cm2 and then decreases to 15% for 1.4 J/cm2. The optimal fluence is situated at 1.1 J/cm2 where 29 ± 8% of the cells are perforated although we obtain excellent results from 1 to 1.1 J/cm2. Viability is higher at 1064 nm and more stable even if the fluence used is approximately 15X higher. The 50% viability threshold for this wavelength is situated at 1.4 J/cm2.

Error bars on Fig. 1c and Fig. 1d show that NIR pulses produce smaller variability in perforation and viability results compared to 532 nm pulses. It is thus more probable to get a high perforation rate for a given experiment using 1064 nm than using a 532 nm wavelength since 1064 nm offers better reproducibility.

It is important to note that according to the ANSI Z136.1-2000 standards the maximum permissible exposure (MPE) for ns pulses at 532 nm is ~20 mJ/cm2 and ~100 mJ/cm2 at 1064 nm. Hence none of the used wavelengths at the operating power would be considered safe for clinical use. The near infrared wavelength is not an asset in terms of irradiance delivered but rather in terms of penetration depth and reproducibility. It may in addition provide insights on mechanisms of membrane perforation.

3.2. MTT assays

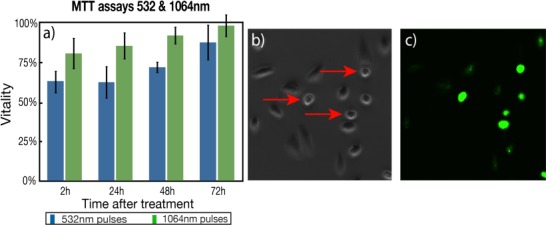

The viability shown on Fig. 1 represents the viability taken 2 h after treatment by PI exclusion. However, since this experiment assesses only membrane integrity, it gives no information about the internal cell metabolism. To address this point, we conducted MTT cell viability assays on cells irradiated with 50 mJ/cm2 for 532 nm and 1 J/cm2 for 1064 nm pulses. This biological assay specifically measures the mitochondrial activity of the cells, allowing for a quantitative measurement of cell vitality. The irradiation conditions are equivalent to the one used for optoporation (cells are loaded with the same AuNPs concentration but no external cargo is added to the solution). Visually, small changes in the shape of the irradiated cells were observed as they were more rounded than the control cells (see Fig. 2(b) ). Most cells however came back to their normal elongated shape after 24 h.

Fig. 2.

(a) Comparison of MTT assay for both lasers up to 72 h after treatment. The cells were able to fully recover without any noticeable effect (n = 4, the error bars represent the standard deviation, results from 2 independent experiences). (b) Phase contrast image showing rounded cells (red arrows) after treatment and (c) corresponding fluorescent image showing intake of LY.

MTT cell vitality measurements at 2 h give 64 ± 7% and 81 ± 10% for 532 nm and 1064 nm, respectively, and are both lower than the viability evaluated by PI exclusion and control images (84 ± 8% and 91 ± 7%, respectively). MTT assay gives information about the cells metabolic activities by measuring the amount of formazan produced by dehydrogenases and reductases mitochondrial enzymes. This result indicates that even if the cells are present and their membrane is intact, their internal metabolism might be slowed down or malfunctioning. The difference is more significant at 532 nm where there is a 20% difference. However, the vitality gradually increases over time and reaches 88 ± 11% and 99 ± 7% after 72 h for 532 nm and 1064 nm respectively. This increase indicates that cells have recovered after irradiation, that they survived and they are proliferating, indicating that their metabolism is back to normal.

3.3. Nanoparticles transformation

SEM measurements were performed to monitor the status of the AuNPs during the treatment. Baumgart et al. [17] recently showed by spectroscopy and SEM that AuNPs stayed intact with fluences up to 600 mJ/cm2 with a femtosecond laser. However, AuNPs have been reported to undergo size reduction when irradiated by nanosecond laser [35,36]. The size reduction may also be accompanied by the creation of smaller fragments (<10 nm). These small fragments may intercalate between DNA segments and induce genetic problems and morphological changes for doses as low as 10 μg/mL [37]. It is therefore crucial to determine if the size reduction process takes place during the treatment.

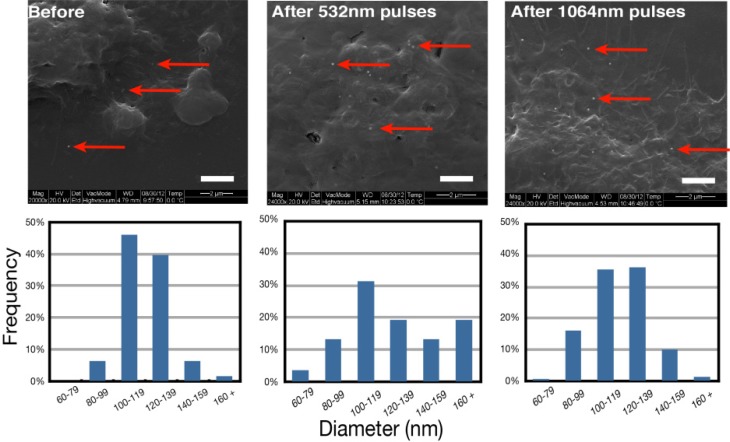

The integrity of the AuNPs has been verified with SEM images taken before and after the treatment. The irradiation was performed at fluences of 50 mJ/cm2 at 532 nm and 1 J/cm2 at 1064 nm. 30 minutes after the treatment, the cells are fixed with glutaraldehyde. The next day, the samples are covered with a 5 nm gold layer and observed in high vacuum mode with the SEM. Figure 3 (left) shows cells loaded with NPs before the laser treatment.

Fig. 3.

SEM images showing AuNPs (red arrows) on cells before and after treatment with their size distribution for both wavelengths. Bar is 2 μm (n = 2, results from 2 independent experiences).

We can see single AuNPs as well as some clusters of 2 and 3 AuNPs just underneath the membrane. Figure 3 (center and right) shows cells that have been irradiated by 532 nm and 1064 nm pulses. The AuNPs diameters have been measured with the SEM software and no significant difference in the AuNPs mean diameter have been found between the irradiated and non-irradiated sample. The mean diameter of NPs before treatment is 120 ± 16 nm while it is 128 ± 33 nm when treatment is performed with 532 nm pulses and 117 ± 20 nm for 1064 nm pulses. However, the size distribution of irradiated samples shows a more disperse population as seen on Fig. 3. This suggests that the AuNPs undergo small transformations. This may lead to the creation of small fragments which could be harmful for cells. However, the MTT assays show positive results which indicate that the effect of small fragments might be negligible. The 532 nm treatment modifies the AuNPs size to a greater extent than the 1064 nm treatment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of pulse width: Femtosecond vs nanosecond pulses

The interaction mechanisms between a pulsed laser and AuNPs are complex processes highly dependent on the pulse wavelength, duration, energy and intensity. High intensity fs pulses can be used to induce non-linear absorption of the laser energy in the plasmonic enhanced near-field in the vicinity of the AuNPs, creating a nanoplasma. For instance, we have previously used 100 mJ/cm2 45 fs off-resonance 800 nm pulses to perforate cells [17]. This fluence yields a local intensity that reaches ~4 x 1013 W/cm2 in the near-field where the field enhancement is calculated to be around 4.5 from the Mie theory. Referring to Vogel et al., this intensity is sufficient to induce important plasma production as the optical breakdown occurs for intensity of 1013 W/cm2 [38]. An electron plasma is hence produced by a combination of photoionization and impact ionization [39]. This plasma transfers its energy to the water molecules very rapidly through collision and recombination processes, yielding large pressure wave and vapor bubbles around the AuNPs. For femtosecond pulse, the energy deposition step is clearly separated from the release of heat to the environment and the cavitation bubble dynamic.

For the nanosecond pulses used at 532 nm and 1064 nm, multiphoton absorption is not expected as the intensity does not reach the optical breakdown threshold. At the optimal fluence (50 mJ/cm2 for 532 nm and 1 J/cm2 for 1064 nm), the near-field intensity reaches 1.5 x 107 W/cm2 and 1.8 x 108 W/cm2 for 532 nm and 1064 nm irradiation while considering the field enhancement. These values are many orders of magnitude below the intensity threshold for optical breakdown calculated by Vogel et al. (6 x 1011 W/cm2 for 532 nm and 2 x 1011 W/cm2 for 1064 nm) [38]. The main mechanism of heat transfer to the surrounding environment is in consequence expected to be energy absorption by the AuNPs with subsequent conduction transfer through the NP/environment interface. Bubble nucleation is usually expected to occur from phase explosion as the temperature approaches the critical temperature [40]. As bubble nucleation occurs in ~100 ps-1 ns, energy deposition for nanosecond laser pulse overlaps with heat transfer and bubble growth around the NPs. In particular, the vapor bubble will quench the energy absorption by the NPs by intense scattering and modification of the resonance condition. The vapor layer also insulates the surrounding environment from the particle, so that plasmon nanobubbles induce highly localized mechanical damage to the surrounding cells [41].

4.2. Effect of wavelength: on (532 nm) vs off (1064 nm) resonance in the nanosecond regime

Plasmon resonance for AuNPs peaks around 530 nm, leading to a strong absorption and scattering, when NPs are irradiated at 532 nm. However, for an irradiation wavelength of 1064 nm, the AuNPs are considered off-resonant and both absorption and scattering efficiencies are strongly reduced (σabs(532 nm) ≈100 σabs(1064 nm) and σscat(532 nm) ≈370 σabs(1064 nm)). It is expected that higher fluences are required to achieve perforation of the cell membrane at 1064 nm than at 532 nm. Results presented in Fig. 1 hence show that the fluence necessary to achieve efficient perforation using a 1064 nm pulse is 20 times higher than for the 532 nm pulse. To explain why the fluence required for efficient perforation is only 20 times higher instead of 100 as predicted by theoretical absorption curves, it is tempting to assume the NPs aggregate. This would broaden the absorption peak and hence decrease the ratio (σabs(532 nm)/σabs(1064 nm), However, the NPs observed under the SEM (section 3.3) just before and after irradiation did not show a high amount of aggregation. Aggregates between 2 and 4 nanoparticles were observed for roughly every 30 single particles.

Cavitation bubble created with nanoseconds pulses at 532 nm have been observed and extensively studied [27,41–44] but so far no study, to our knowledge, have reported bubbles created with ns pulses at 1064 nm. Using the optical set-up described in [45], preliminary data shows the generation of nanobubbles with 1064 nm pulses but only for fluences above 10 J/cm2. The model of Pustovalov et al. [46] describing the laser heating of AuNPs in water can be used to obtain an estimation of the temperature increase at the AuNP boundary. Using classical values for the gold and water thermodynamic properties, as well as the absorption cross-section given by the Mie theory for the AuNPs, the temperature in the water following a 15 ns, 532 nm irradiation reaches between 1231 K and 4050 K, which is way over the 0.9 Tc limit (582 K) usually taken as the cavitation onset [47]. It is thus reasonable to attribute the perforation mechanism to the formation of vapor bubble in the case of 532 nm irradiation at this range of fluence. Note that this model overestimates temperature higher than the gold melting point (~1337 K), which however does not affect our conclusion.

In the case of a 1064 nm, 75 ns irradiation, the temperature in the water only reaches 340 K-411 K for fluences ranging from 0.6 J/cm2 to 1.5 J/cm2. Those temperatures are much lower than the 0.9 Tc limit, and it is thus doubtful that the formation of vapor bubble is at the origin of the perforation mechanism at these fluences. The temperature is however still significant (67°C −138°C) and could reasonably induce an increase in the membrane fluidity and permeability and be at the origin of the molecular uptake. The exact mechanism of membrane permeabilization remains unclear but these results indicate that the perforation mechanism at 1064 nm might be purely thermal. A similar mechanism has been reported by Nikolskaya et al. [48] in their study of membrane permeabilization with a continuous diode laser. No vapor bubbles were associated with the permeabilization process and they proposed heating of phenol red and other absorbing dyes as the main mechanism for permeabilization. Further studies are required to determine the near infrared plasmonic enhanced laser optoporation process.

5. Conclusion

We demonstrate that membrane permeabilization with AuNPs irradiated by off LSPR nanosecond pulses (1064 nm) is achievable and, in our case, yields to slightly improved results compared with on resonance 532 nm wavelength irradiation. Both wavelengths generate optimal perforation rate above 25% but the 1064 nm pulses provide better viability according to MTT and PI exclusion tests. The 2 h viability is sligthy affected at the optimal fluences and vitality MTT assays reaches 88% for 532 nm pulses and 98% for 1064 nm 72 h after treatment. Damages to AuNPs following irradiation with 532 nm pulses are slightly more important when compared to 1064 nm pulses at the treatment fluence. The results obtained with NIR pulses offer better reproducibility than those obtained with 532 nm pulses. In addition, the optoporation throughput is relatively high, with the treatment of 10000 cells/min. These optoporation results show great promises for cell transfection. However, since a DNA plasmid is much larger than the fluorescent dye used for optoporation measurements, more tests are needed to obtain transfection efficiency results.

While the cell permeabilization mechanism for the 532 nm wavelength is associated to the production of nanoscale vapor bubbles around the AuNPs, the situation is less clear with 1064 nm irradiation, where permeabilization seems associated to a heating process, much similar to the case of continuous laser optoporation. When compared to off-resonance ultrafast laser optoporation, off-resonance nanosecond optoporation is shown to be less efficient (30% compared to 70% from our previous studies [17]). The viabilities of the two methods are comparable even though nanosecond pulses induce small transformation of the AuNPs. However, the relatively high cost and complexity of ultrafast laser justifies the interest for nanosecond off-resonance plasmonic enhanced cell transfection.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by “Fonds de recherche du Québec—Nature et technologies” (FQRNT). The authors also thank Yves Drolet for technical support and Rémi Lachaine, Ali Hatef, Eric Bergeron and Judith Baumgart for fruitful discussions. The authors also greatly appreciate the help of Laure Humbert for the preparation on biological samples and François Bissonnette for art work.

References and links

- 1.B. Alberts, D. Bray, K. Hopkin, A. Johnson, J. Lewis, M. Raff, K. Roberts, and P. Walter, Essential Cell Biology, 2nd ed. (Garland Science, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li S. D., Huang L., “Gene therapy progress and prospects: non-viral gene therapy by systemic delivery,” Gene Ther. 13(18), 1313–1319 (2006). 10.1038/sj.gt.3302838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patil P. M., Chaudharie P. D., Sahu M., Duragkar J., “Review article on gene therapy,” Int. J. Genetics 4, 74–79 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehead K. A., Langer R., Anderson D. G., “Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery,” Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8(2), 129–138 (2009). 10.1038/nrd2742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florea S., Andreeva K., Machado C., Mirabito P. M., Schardl C. L., “Elimination of marker genes from transformed filamentous fungi by unselected transient transfection with a Cre-expressing plasmid,” Fungal Genet. Biol. 46(10), 721–730 (2009). 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans C. H., Ghivizzani S. C., Robbins P. D., “Arthritis gene therapy’s first death,” Arthritis Res. Ther. 10(3), 110 (2008). 10.1186/ar2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehrman S., “Virus treatment questioned after gene therapy death,” Nature 401(6753), 517–518 (1999). 10.1038/43977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pathak A., Patnaik S., Gupta K. C., “Recent trends in non-viral vector-mediated gene delivery,” Biotechnol. J. 4(11), 1559–1572 (2009). 10.1002/biot.200900161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Y., Zheng Z., Cohen C. J., Gattinoni L., Palmer D. C., Restifo N. P., Rosenberg S. A., Morgan R. A., “High-efficiency transfection of primary human and mouse T lymphocytes using RNA electroporation,” Mol. Ther. 13(1), 151–159 (2006). 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mir L. M., “Nucleic acids electrotransfer-based gene therapy (electrogenetherapy): past, current, and future,” Mol. Biotechnol. 43(2), 167–176 (2009). 10.1007/s12033-009-9192-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y., Yu L. C., “Single-cell microinjection technology in cell biology,” Bioessays 30(6), 606–610 (2008). 10.1002/bies.20759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogura M., Sato S., Nakanishi K., Uenoyama M., Kiyozumi T., Saitoh D., Ikeda T., Ashida H., Obara M., “In vivo targeted gene transfer in skin by the use of laser-induced stress waves,” Lasers Surg. Med. 34(3), 242–248 (2004). 10.1002/lsm.20024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takano S., Sato S., Terakawa M., Asida H., Okano H., Obara M., “Enhanced transfection efficiency in laser-induced stress wave-assisted gene transfer at low laser fluence by increasing pressure impulse,” Appl. Phys. Express 1, 038001 (2008). 10.1143/APEX.1.038001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei M., Xu H., Yang H., Yao B., “Femtosecond laser-assisted microinjection into living neurons,” J. Neurosci. Methods 174(2), 215–218 (2008). 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumgart J., Bintig W., Ngezahayo A., Willenbrock S., Murua Escobar H., Ertmer W., Lubatschowski H., Heisterkamp A., “Quantified femtosecond laser based opto-perforation of living GFSHR-17 and MTH53 a cells,” Opt. Express 16(5), 3021–3031 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.003021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitsillides C. M., Joe E. K., Wei X., Anderson R. R., Lin C. P., “Selective cell targeting with light-absorbing microparticles and nanoparticles,” Biophys. J. 84(6), 4023–4032 (2003). 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75128-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumgart J., Humbert L., Boulais É., Lachaine R., Lebrun J. J., Meunier M., “Off-resonance plasmonic enhanced femtosecond laser optoporation and transfection of cancer cells,” Biomaterials 33(7), 2345–2350 (2012). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao C., Rahmanzadeh R., Endl E., Zhang Z., Gerdes J., Hüttmann G., “Elevation of plasma membrane permeability by laser irradiation of selectively bound nanoparticles,” J. Biomed. Opt. 10(6), 064012 (2005). 10.1117/1.2137321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukianova-Hleb E. Y., Wagner D. S., Brenner M. K., Lapotko D. O., “Cell-specific transmembrane injection of molecular cargo with gold nanoparticle-generated transient plasmonic nanobubbles,” Biomaterials 33(21), 5441–5450 (2012). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.K. Sankaranarayanan, S. Radhakrishnan, S. Kanagaraj, R. Rajendran, S. Shahid, P. Kathirvel, V. Sundaresan, V. K. Udayakumar, R. Ramachandran, and R. Sundararajan, “Effect of Irreversible electroporation on cell proliferation in fibroblasts,” Proceedings of the ESA Annual Meeting on Electrostatics (2011), pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canatella P. J., Karr J. F., Petros J. A., Prausnitz M. R., “Quantitative study of electroporation-mediated molecular uptake and cell viability,” Biophys. J. 80(2), 755–764 (2001). 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76055-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farokhzad O. C., Langer R., “Impact of nanotechnology on drug delivery,” ACS Nano 3(1), 16–20 (2009). 10.1021/nn900002m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukianova-Hleb E. Y., Belyanin A., Kashinath S., Wu X., Lapotko D. O., “Plasmonic nanobubble-enhanced endosomal escape processes for selective and guided intracellular delivery of chemotherapy to drug-resistant cancer cells,” Biomaterials 33(6), 1821–1826 (2012). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pissuwan D., Valenzuela S. M., Cortie M. B., “Therapeutic possibilities of plasmonically heated gold nanoparticles,” Trends Biotechnol. 24(2), 62–67 (2006). 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapotko D., Lukianova E., Potapnev M., Aleinikova O., Oraevsky A., “Method of laser activated nano-thermolysis for elimination of tumor cells,” Cancer Lett. 239(1), 36–45 (2006). 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Letfullin R. R., Joenathan C., George T. F., Zharov V. P., “Laser-induced explosion of gold nanoparticles: potential role for nanophotothermolysis of cancer,” Nanomedicine (Lond) 1(4), 473–480 (2006). 10.2217/17435889.1.4.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lapotko D. O., Lukianova E. Y., Oraevsky A. A., “Selective laser nano-thermolysis of human leukemia cells with microbubbles generated around clusters of gold nanoparticles,” Lasers Surg. Med. 38(6), 631–642 (2006). 10.1002/lsm.20359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Link S., El-Sayed M. A., “Spectral Properties and Relaxation Dynamics of Surface Plasmon Electronic Oscillations in Gold and Silver Nanodots and Nanorods,” J. Phys. Chem. B 103(40), 8410–8426 (1999). 10.1021/jp9917648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eustis S., el-Sayed M. A., “Why gold nanoparticles are more precious than pretty gold: noble metal surface plasmon resonance and its enhancement of the radiative and nonradiative properties of nanocrystals of different shapes,” Chem. Soc. Rev. 35(3), 209–217 (2006). 10.1039/b514191e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain P. K., El-Sayed I. H., El-Sayed M. A., “Au nanoparticles target cancer,” Nano Today 2(1), 18–29 (2007). 10.1016/S1748-0132(07)70016-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiwari P. M., Vig K., Dennis V. A., Singh S. R., “Functionalized gold nanoparticles and their biomedical applications,” J. Nanomater. 1(1), 31–63 (2011). 10.3390/nano1010031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukianova-Hleb E. Y., Samaniego A. P., Wen J., Metelitsa L. S., Chang C. C., Lapotko D. O., “Selective gene transfection of individual cells in vitro with plasmonic nanobubbles,” J. Control. Release 152(2), 286–293 (2011). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao C., Qu X., Zhang Z., Hüttmann G., Rahmanzadeh R., “Influence of laser parameters on nanoparticle-induced membrane permeabilization,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14(5), 054034 (2009). 10.1117/1.3253320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bashkatov A. N., Genina E. A., Kochubey V. I., Tuchin V. V., “Optical properties of human skin, subcutaneous and mucous tissues in the wavelength range from 400 to 2000 nm,” J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 38(15), 2543–2555 (2005). 10.1088/0022-3727/38/15/004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inasawa S., Sugiyama M., Yamaguchi Y., “Laser-induced shape transformation of gold nanoparticles below the melting point: the effect of surface melting,” J. Phys. Chem. B 109(8), 3104–3111 (2005). 10.1021/jp045167j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takami A., Kurita H., Koda S., “Laser-induced size reduction of noble metal particles,” J. Phys. Chem. B 103(8), 1226–1232 (1999). 10.1021/jp983503o [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaeublin N. M., Braydich-Stolle L. K., Schrand A. M., Miller J. M., Hutchison J., Schlager J. J., Hussain S. M., “Surface charge of gold nanoparticles mediates mechanism of toxicity,” Nanoscale 3(2), 410–420 (2011). 10.1039/c0nr00478b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogel A., Noack J., Hüttman G., Paltauf G., “Mechanisms of femtosecond laser nanosurgery of cells and tissues,” Appl. Phys. B 81(8), 1015–1047 (2005). 10.1007/s00340-005-2036-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boulais É., Lachaine R., Meunier M., “Plasma mediated off-resonance plasmonic enhanced ultrafast laser-induced nanocavitation,” Nano Lett. 12(9), 4763–4769 (2012). 10.1021/nl302200w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vogel A., Venugopalan V., “Mechanisms of pulsed laser ablation of biological tissues,” Chem. Rev. 103(2), 577–644 (2003). 10.1021/cr010379n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukianova-Hleb E. Y., Hu Y., Latterini L., Tarpani L., Lee S., Drezek R. A., Hafner J. H., Lapotko D. O., “Plasmonic nanobubbles as transient vapor nanobubbles generated around plasmonic nanoparticles,” ACS Nano 4(4), 2109–2123 (2010). 10.1021/nn1000222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lukianova-Hleb E. Y., Hanna E. Y., Hafner J. H., Lapotko D. O., “Tunable plasmonic nanobubbles for cell theranostics,” Nanotechnology 21(8), 085102 (2010). 10.1088/0957-4484/21/8/085102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitz M., Preisser S., Wetterwald A., Jaeger M., Thalmann G. N., Frenz M., “Vapor bubble generation around gold nano-particles and its application to damaging of cells,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(2), 291–304 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.000291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lukianova-Hleb E. Y., Santiago C., Wagner D. S., Hafner J. H., Lapotko D. O., “Generation and detection of plasmonic nanobubbles in zebrafish,” Nanotechnology 21(22), 225102 (2010). 10.1088/0957-4484/21/22/225102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lachaine R., Boulais E., Bourbeau E., Meunier M., “Effect of pulse duration on plasmonic enhanced ultrafast laser-induced bubble generation in water,” Appl. Phys., A Mater. Sci. Process. 2012(Sept.) 1–4 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pustovalov V. K., Smetannikov A. S., Zharov V. P., “Photothermal and accompanied phenomena of selective nanophotothermolysis with gold nanoparticles and laser pulses,” Laser Phys. Lett. 5(11), 775–792 (2008). 10.1002/lapl.200810072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ekici O., Harrison R. K., Durr N. J., Eversole D. S., Lee M., Ben-Yakar A., “Thermal analysis of gold nanorods heated with femtosecond laser pulses,” J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 41(18), 185501 (2008). 10.1088/0022-3727/41/18/185501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikolskaya A. V., Nikolski V. P., Efimov I. R., “Gene printer: laser-scanning targeted transfection of cultured cardiac neonatal rat cells,” Cell Commun. Adhes. 13(4), 217–222 (2006). 10.1080/15419060600848524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]