Abstract

Global trade of biomass-related products is growing exponentially, resulting in increasing ‘teleconnections’ between producing and consuming regions. Sustainable management of the earth's lands requires indicators to monitor these connections across regions and scales. The ‘embodied human appropriation of NPP’ (eHANPP) allows one to consistently attribute the HANPP resulting from production chains to consumers. HANPP is the sum of land-use induced NPP changes and biomass harvest. We present the first national-level assessment of embodied HANPP related to agriculture based on a calculation using bilateral trade matrices. The dataset allows (1) the tracing of the biomass-based products consumed in Austria in the year 2000 to their countries of origin and quantifying the HANPP caused in production, and (2) the assigning of the national-level HANPP on Austria's territory to the consumers of the products on the national level. The dataset is constructed along a consistent system boundary between society and ecosystems and can be used to assess Austria's physical trade balance in terms of eHANPP. Austria's eHANPP-trade balance is slightly negative (imports are larger than exports); import and export flows are large in relation to national HANPP. Our findings show how the eHANPP approach can be used for quantifying and mapping the teleconnections related to a nation's biomass metabolism.

Keywords: Human appropriation of net primary production (HANPP), Embodied HANPP (eHANPP), Trade, Austria, Biomass, Food

Highlights

► Embodied HANPP (eHANPP) is a consumption-based indicator of resource use. ► eHANPP is defined as the human appropriation of net primary production resulting from provision of a product. ► We demonstrate how to calculate national eHANPP based on FAO statistics for Austria's agricultural biomass flows. ► We find substantial trade-related flows compared to national HANPP. ► eHANPP can help to analyse 'teleconnections' in the global land system.

1. Introduction

The role of international trade in supplying countries with biophysical resources is growing. Trade has been important for the supply of many nations with resources such as fossil energy, metals or minerals for a long time, but meanwhile it is also increasingly relevant for agricultural products. From 1961 to 2009, global gross biomass trade grew exponentially at a rate of 4% per year, i.e. considerably faster than global biomass production which grew at 2% (FAO, 2010).

Surging trade results in a growing ‘spatial disconnect’ between the location of the production of biomass-based products and the places where they are consumed (Erb et al., 2009b). This phenomenon leads to global ‘teleconnections’ (or ‘telecouplings’) in the land system (Haberl et al., 2009a; Seto et al., 2012). Teleconnections have been defined as ‘correlation(s) between specific planetary processes in one region of the world to distant and seemingly unconnected regions elsewhere’ (Steffen, 2006, p. 156). Sustainable management of global land resources as well as land-based products such as food, feed, fiber and bioenergy requires a much better understanding of these interconnections than we have today. The ongoing debate on ‘indirect land-use change’ (iLUC) effects of European and US bioenergy policies is a prominent example (Fargione et al., 2008; Searchinger et al., 2008). Hence, there is a growing need for concepts to monitor such interrelations (Hornborg and Jorgenson, 2010; van den Bergh and Verbruggen, 1999) which is why teleconnections are being increasingly discussed (e.g., Seto et al., 2012). Indicators such as the one discussed in this paper can help to analyze trade-related teleconnections (Haberl et al., 2009a).

In the last years, different approaches have been developed to account for environmental effects related to traded products. One prominent approach is the ‘carbon footprint’, i.e. the CO2 ‘embodied’ in traded products (Davis and Caldeira, 2011; Hertwich and Peters, 2009; Peters and Hertwich, 2008; Peters et al., 2011). This method allows the accounting for the CO2 emissions resulting from fossil fuel combustion associated with internationally traded products. The ‘water footprint’ or ‘virtual water’ approach is a related concept to measure the volume of water required for the production of traded goods (Gerbens-Leenes et al., 2009; Hoekstra and Hung, 2005). Greenhouse gas emissions related with traded biomass-based products have also been calculated (Gavrilova et al., 2010), although the full effects of land-use changes on the GHG balance of traded biomass-based products still need to be quantified. Land area required in producing traded goods has been assessed with the ‘Actual Land Demand’ approach (Erb, 2004), and international wood product trade has been linked to national level forest stock change (Kastner et al., 2011a). Pressures on biodiversity related to international trade were recently analyzed by Lenzen et al. (2012). Similar accounts for human demands on ecosystems related to biomass flows are so far missing.

In order to help in closing this gap, this article applies the concept of the human appropriation of net primary production (HANPP) ‘embodied’ in consumed and/or traded agricultural products (denoted as ‘embodied HANPP’ and abbreviated as ‘eHANPP’) to Austria. ‘Embodied HANPP’ is an extension of HANPP, an environmental pressure indicator that is based on the analysis of human impacts on trophic energy (or biomass) flows in ecosystems (for definitions see below). The HANPP concept was proposed over two decades ago (Vitousek et al., 1986; Wright, 1990) and has so far mostly been used for territorial accounts, i.e. in production-based approaches (Haberl et al., 2007a).

In the last years, a complementary, consumption-based definition of HANPP has been developed (Imhoff et al., 2004) and denoted as ‘embodied HANPP’ (Erb et al., 2009b; Haberl et al., 2009a; Haberl et al., 2012b). Embodied HANPP is defined as the HANPP resulting from the production of any product along the production chain (Erb et al., 2009b; Haberl et al., 2009a). So far, two global eHANPP datasets are available (Imhoff et al., 20041; Erb et al., 2009b). Both datasets are based on country-level data on the apparent consumption (domestic extraction plus import minus export) of biomass-based products; both of them account for differences in domestic production and consumption only for highly aggregated groups of biomass products and do not break down imports to the countries of origin. Thus, differences in production related to the upstream flows are not considered. While this approach allows us to give an aggregated overview of the ‘spatial disconnect’ between production and consumption at the global level (Erb et al., 2009b), it does neither allow us to assess detailed bilateral trade flows between individual countries (i.e. it is not possible to map from where the imports of a country come or where the exports are going to), nor can it be used to evaluate eHANPP at the product level. Moreover, both datasets were established using highly aggregated multipliers, thereby creating inaccuracies due to differences in agricultural intensity (e.g. technology), soil and climate conditions, etc., between regions and products.

In this article we present an account of the embodied HANPP related to agriculture for one country (in this case Austria) based on detailed bilateral trade matrices in physical units. The analysis only considers agricultural products, a major component of global HANPP (78.3% of global HANPP in 2000; Haberl et al., 2007a). Forestry, infrastructure areas and human-induced fires were not considered in this study. Austria's import and export flows of wood products and the related felling losses are very large and both amount to approximately 12 million tons of dry-matter biomass per year; that is, net trade (import minus export) is close to zero (Kastner et al., 2011a). While adding forestry is conceptually rather straightforward (but data intensive), infrastructure and fires are difficult to link to biomass trade because only some of these phenomena are directly linked to production and/or trade. Accounting for these flows was beyond the scope of this paper.

The dataset discussed in this article is explicit in terms of countries of origin of products consumed in Austria as well as the destination of products produced on Austria's territory. The year 2000 was chosen for reasons of data availability (see below). In order to demonstrate the usefulness of the method to analyze national interdependencies in a double-counting free, consistent approach, we provide a detailed analysis of the consumption of the eHANPP flows related to animal-based food, a particularly intricate component due to the large upstream requirements and complex product/by-product structure.

2. Methods

2.1. Definition of Embodied HANPP

Net primary production (NPP) is the production of organic materials by plants through photosynthesis net of the plant's own metabolism. NPP is the total amount of energy available for ecological food webs and reproduction of ecological biomass stocks (standing biomass of plants and soil organic carbon). The ‘human appropriation of net primary production’ (HANPP) accounts for the human impact on this ecological energy flow, and quite a few definitions on how to measure HANPP exist, depending on the choice of more or less inclusive system boundaries (Erb et al., 2009a; Vitousek et al., 1986). We used the conventions of Haberl et al. (2007a) who defined HANPP as the sum total of human-induced changes of NPP, denoted as ∆NPPLC (which stands for ‘change in NPP resulting from land conversion’) plus (2) biomass harvest, denoted as NPPh (for NPP harvested). NPPh includes not only the biomass that actually enters economic production chains but also by-flows such as plant parts killed during harvest (roots, unused straw, etc.) and human-induced fires (Lauk and Erb, 2009). This latter flow was not considered in this study because many fires are not (or not directly) related to production activities (and can hence not be attributed to traded products) and the share of fires related to agricultural production as well as the biomass burned in these fires is unknown. The concept of HANPP outlined above is inclusive in that it encompasses all changes of ecological energy flows and not only biomass directly consumed by humans, and has been shown to be useful for mapping and quantifying environmental pressures on any defined area of land, e.g. for national territories (Haberl et al., 2007a). If applied to a nation state, HANPP related to imported products is not added, and HANPP on national territory stemming from the production of exported goods is not subtracted.

Embodied HANPP (Fig. 1) is defined as the HANPP related to the full process chain of a product, i.e. it is based on a Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) approach (Rebitzer et al., 2004). Factors can be used to account for conversion losses, by-flows of unused biomass as well as changes in NPP resulting from land use (∆NPPLC), calculated with the same system boundaries as those of Haberl et al.'s (2007a). At the national scale, HANPP embodied in the apparent consumption of biomass products can be assessed by calculating HANPP on the national territory plus the amount of HANPP embodied in imports minus eHANPP of exports.

Fig. 1.

Embodied HANPP is calculated by adding conversion losses, by-flows of unused biomass and productivity changes resulting from land use (∆NPPLC) along the process chain.

Source: redrawn after Haberl et al., 2009a.

2.2. Data Requirements and Data Sources

The data quality of an eHANPP calculation largely depends on the quality of the factors used to calculate losses, unused biomass and ∆NPPLC. For this reason we chose to perform the calculations for the year 2000 because a consistent global database exists for this year. This database includes: (1) a high resolution global HANPP dataset (Haberl et al., 2007a), (2) a global land-use dataset on a 5 arc min (approximately 10 per 10 km at the equator) GIS raster (Erb et al., 2007), and (3) a global national-level biomass flow dataset that traces biomass flows from production to consumption, and in particular includes feed balances of livestock that are indispensable for calculating the eHANPP of animal products (Krausmann et al., 2008). As a source of trade data we used FAO bilateral trade data (FAO, 2010) which cover approximately 500 products and 200 countries in monetary and biophysical units; we used the latter. All data were harmonized to tons of dry matter biomass using standard factors from the literature (for reference see Haberl et al., 2007a and Krausmann et al., 2008).

2.3. The Accounting System

Two separate accounts were established:

-

(1)

The origin account reports the eHANPP resulting from the biomass-based products consumed in Austria, indicating the corresponding origin at the national level. It uses the concept of ‘apparent consumption’, i.e. the total consumption in Austria's national economy in the year 2000 (domestic extraction plus import minus export). Re-exported goods, including imported products used to produce exported goods, are not included in this account.

-

(2)

The destination account reports the location of apparent consumption, including Austria itself, of goods produced in Austria and assigns the HANPP occurring on Austria's territory to them.

Once these two accounts are established it is possible to calculate Austria's eHANPP trade balance by subtracting (1) from (2). The trade balance can be calculated for individual products, groups of products, individual trade partners and groups of countries, and for different land-use types. We here report results separately for cropland and grazing land at the level of national trading partners of Austria.

The calculations in this paper consider 40 primary products (Table 1), linked to over 350 processed products, covering over 90% of Austria's imports and exports in terms of their dry matter mass. Secondary products (e.g., flour, soy cake) were converted into primary product equivalents (e.g., wheat, soy beans) using conversion factors based on FAO (2003) combined with factors on dry matter content taken from Haberl et al. (2007a, 2007b) and Krausmann et al. (2008). This approach was chosen in order to be able to consistently link processed products to their primary product equivalents in the case of combined production processes with several products (e.g., soy is used to produce oil and cake in the same production process; see Kastner et al., 2011a). Note that this dry-weight based allocation is only one of several possible allocation options; different allocation methods (e.g., based on economic value or energy content) sometimes give substantially different results even if based on the same underlying data (Haes et al., 2000; Jungmeier et al., 2002; Weidema, 2000).2

Table 1.

Primary products included in the eHANPP calculation.

| Wheat | Beans | Coffee | Peas | Strawberries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Groundnuts | Rye | Apples | Sugar crops |

| Maize | Sunflower seeds | Sweet potatoes | Plantain | |

| Soybeans | Potatoes | Cowpeas | Pulses | Monogastric livestock |

| Barley | Cassava | Olives | Banana | Products (chicken and pig meat, eggs) |

| Sorghum | Vegetables | Rubber | Pigeon peas | |

| Millet | Oats | Grapes | Tobacco | |

| Cotton | Coconuts | Cocoa | Tomatoes | Ruminant livestock |

| Rapeseed | Chickpeas | Sesame seed | Oranges | Products (milk and beef) |

One central challenge when linking apparent consumption to the origin of crop products is the phenomenon of re-exports. For example, according to trade statistics, a large percentage of Austria's soy consumption is imported from Germany, although no substantial amounts of soy are produced there. The reason is that any processing step, however small, related to a soy product imported to Germany results in its classification as being ‘German’ in origin (Gavrilova et al., 2010). In order to assign the soy (and all other products in our calculation) to the correct country of origin we used a method that combines trade data with production data (Kastner et al., 2011b). This approach assumes homogenous composition of domestic consumption and export: if, for instance, country A imports 95% and produces 5% of a product, the method assigns the same fractions to both export and domestic consumptions. This method is data intensive, as it requires not only a complete global dataset for trade flows, but also global country-level production data at the crop level (we used FAO, 2010).

2.4. HANPP Factors

The above-discussed procedures resulted in a consistent allocation of domestic consumption of agricultural biomass to primary products and countries of origin. To assess the eHANPP associated with these flows, we established so-called HANPP factors: these indicate the amount of HANPP linked to the production of 1 unit of primary biomass product. For HANPP occurring on grasslands this was straightforward: we associated the entire grassland HANPP (taken from Haberl et al., 2007a) of a nation to its output in ruminant products and derived the respective factor from this ratio. This approach was chosen because feedstuff from grazing lands (hay, roughage) is usually not traded. We applied the same logic to fodder crops (for specific problems related to livestock see Section 2.5).

For cropland products a two-step process was necessary to derive crop specific HANPP factors (refer to Fig. 1):

-

(1)

The NPPh considered in HANPP calculations includes not only used products covered by statistics but also products not or only partially covered (e.g., straw use as feedstuff) as well as by-products and by-flows such as unrecovered straw, roots killed during harvest, etc.

-

(2)

Changes in productivity resulting from conversion of natural vegetation to the respective crops had to be considered (∆NPPLC). This item includes productivity changes resulting from conversion of natural ecosystems to agro-ecosystems, e.g. deforestation.3

The set of factors to derive NPPh from primary products was generated from previous work (Haberl et al., 2007a; Krausmann et al., 2008). In cases where crop-specific factors were not available in these sources (e.g. strawberries, coconuts, chickpeas), we used average country-specific factors of all crops for which data were available. This may introduce minor inaccuracies, but most likely no major distortions. Calculation of ∆NPPLC factors was less straightforward because the dataset of Haberl et al. (2007a) contains only one average number for ∆NPPLC of the entire cropland in a country; i.e. no crop-specific values were available. To calculate these factors, we developed the following approach: we calculated NPPact per unit of land for all covered crops and countries, using the factors described above. Subsequently we used values on NPP0 per unit of cropland to compute crop and country-specific factors for ∆NPPLC. The values calculated this way can be assumed to be robust in most cases, but distortions can occur if different crops are grown on land of different quality (and thus on areas with different NPP0 values) in a country of origin.4

2.5. Animal Products

Globally, almost 60% of all used biomass extraction is fed to domesticated animals (Krausmann et al., 2008), highlighting the central role livestock products play in the proposed accounting scheme. For the Austrian production system we distinguished between domestic production and imports of animal products; trade in feedstuff was covered in the approach described above. We applied the method explained in Kastner et al. (2011b; see above) to deal with re-exports of animal products. For animal products produced in Austria we used detailed feed balance data (FAO, 2010) to account for the embodied feed products, distinguishing feed originating from Austria and elsewhere. For imported animal products we used basic, nation-specific upstream multipliers derived from Krausmann et al. (2008), distinguishing between products of ruminant and monogastric livestock species. With respect to livestock feed, these multipliers account for market feed (e.g., cereals, oilseed cakes), fodder crops that are in general not traded internationally (e.g., maize for silage), and grazed biomass. The two latter categories were both allocated to products from ruminant livestock.

In order to demonstrate the usefulness of the eHANPP concept for analyzing consumption patterns, we specifically discuss the embodied HANPP related to the consumption of animal-based products in Austria using the above-described databases to quantify ratios between final product consumption, the resulting feed demand and the global HANPP resulting from producing this feed.

3. Results

We found that the embodied HANPP related to Austria's apparent consumption of agricultural products (i.e. the ‘origin account’) is approximately 5% larger than the HANPP related to domestic production (‘destination account’), i.e. Austria is running a trade deficit in terms of eHANPP, a net-importer by approximately 5% of its domestic consumption (Table 2). With respect to cropland-based products, Austria's net imports are substantial (− 16% of domestic consumption), whereas Austria is a net exporter with respect to products associated with grazing land (+ 11% of domestic consumption).

Table 2.

Embodied HANPP in Austria: aggregate results of the origin account, the destination account and the trade balance.

| eHANPP [Mt dry matter/yr] |

eHANPP [% of total (1)] |

|

|---|---|---|

| (1) Origin account (eHANPP related to Austria's consumption) | ||

| Cropland | 18.97 | 68% |

| Grazing land | 9.08 | 32% |

| Total | 28.05 | 100% |

| (2) Destination account (eHANPP related to Austria's production) | ||

| Cropland | 14.52 | 52% |

| Grazing land | 12.11 | 43% |

| Total | 26.62 | 95% |

| (3) Trade balance (negative value = net import) | ||

| Cropland | − 4.45 | − 16% |

| Grazing land | 3.03 | 11% |

| Total | − 1.43 | − 5% |

The origin account (upper part of Table 3) shows that only about half of the eHANPP related to cropland products consumed within Austria is produced in Austria. The three most important countries from which Austria imports are Germany, Hungary and Brazil. The destination account (lower part) shows that almost two thirds of the cropland-related HANPP in Austria results from producing goods that are consumed in Austria; the largest exports from Austria are to Italy, Germany and Turkey. Interestingly, imports are more diversified – the 10 most important countries of origin account for 83% of all eHANPP related to products consumed in Austria – than the exports (the 10 largest countries of destination account for 91% of the total).

Table 3.

Embodied HANPP related to cropland, Austria 2000, breakdown by countries of origin respectively destination.

| Rank | Country name | eHANPP [Mt/yr] | Share in total [%] | Cumulative share [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Origin account | ||||

| 1 | Austria | 9.56 | 50.4% | 50% |

| 2 | Germany | 1.82 | 9.6% | 60% |

| 3 | Hungary | 1.06 | 5.6% | 66% |

| 4 | Brazil | 0.95 | 5.0% | 71% |

| 5 | Argentina | 0.50 | 2.6% | 73% |

| 6 | France | 0.48 | 2.5% | 76% |

| 7 | United States of America | 0.45 | 2.4% | 78% |

| 8 | Italy | 0.44 | 2.3% | 80% |

| 9 | Côte dIvoire | 0.42 | 2.2% | 83% |

| other | 3.28 | 17.3% | 100% | |

| Total | 18.97 | 100.0% | n.d. | |

| (2) Destination account | ||||

| 1 | Austria | 9.56 | 65.9% | 66% |

| 2 | Italy | 1.82 | 12.6% | 78% |

| 3 | Germany | 0.77 | 5.3% | 84% |

| 4 | Turkey | 0.32 | 2.2% | 86% |

| 5 | Russian Federation | 0.17 | 1.2% | 87% |

| 6 | Greece | 0.15 | 1.0% | 88% |

| 7 | Czech Republic | 0.15 | 1.0% | 89% |

| 8 | Hungary | 0.15 | 1.0% | 90% |

| 9 | Romania | 0.14 | 0.9% | 91% |

| Other | 1.27 | 8.8% | 100% | |

| Total | 14.52 | 100.0% | n.d. | |

When it is broken down by products (Table 4), the origin account shows that 57% of the eHANPP associated with cropland products are fed to livestock, followed by wheat (9%) and many other relatively small items. Note that this does not include ruminant grazing, as this account only refers to croplands and thus only includes feedstuff from cropland. The destination account (lower part of Table 4) shows that a large fraction of the cropland products produced in Austria is fed to livestock as well. In both cases, wheat and maize are the most important plant-based products.

Table 4.

Embodied HANPP related to cropland, Austria 2000, breakdown by products.

| Rank | Item | eHANPP [Mt/yr] |

Share in total | Cumulative share | Produced/consumed in Austria | Domestic share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Origin account | ||||||

| 1 | Ruminant products | 5.7 | 30% | 30% | 3.35 | 59% |

| 2 | Monogastric products | 5.2 | 27% | 57% | 2.19 | 42% |

| 3 | Wheat | 1.7 | 9% | 66% | 1.27 | 77% |

| 4 | Maize | 0.8 | 4% | 70% | 0.79 | 93% |

| 5 | Rapeseed | 0.7 | 4% | 74% | 0.29 | 40% |

| 6 | Cocoa | 0.7 | 4% | 78% | – | 0% |

| 7 | Apples | 0.5 | 3% | 80% | 0.27 | 54% |

| 8 | Sunflower | 0.5 | 3% | 83% | 0.11 | 23% |

| 9 | Coffee | 0.5 | 2% | 85% | – | 0% |

| Other | 2.8 | 15% | 100% | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Total | 19.0 | 100% | ||||

| (2) Destination account | ||||||

| 1 | Ruminant products | 5.26 | 36% | 36% | 3.35 | 64% |

| 2 | Monogastric products | 2.75 | 19% | 55% | 2.19 | 79% |

| 3 | Wheat | 2.44 | 17% | 72% | 1.27 | 52% |

| 4 | Maize | 0.92 | 6% | 78% | 0.79 | 86% |

| 5 | Barley | 0.77 | 5% | 84% | 0.14 | 18% |

| 6 | Sugar | 0.43 | 3% | 87% | 0.29 | 68% |

| 7 | Rape | 0.43 | 3% | 89% | 0.29 | 69% |

| 8 | Rye | 0.34 | 2% | 92% | 0.29 | 87% |

| 9 | Apples | 0.30 | 2% | 94% | 0.27 | 90% |

| Other | 0.89 | 6% | 100% | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Total | 14.52 | 100% | ||||

Austria's embodied HANPP related to grassland broken down by countries is reported in Table 5. In this case, we do not present a breakdown by products because there are only two products, i.e. milk and ruminant meat. The origin account shows that a much larger fraction of the total eHANPP stemming from grassland-related products is located in Austria than for cropland products. But despite Austria's status as a net exporter, a substantial fraction is derived from imports, with Germany, the Netherlands and Australia being the top three countries in this respect. The destination account (lower part of Table 5) shows that about two thirds of eHANPP stemming from grassland-related products generated within Austria is also consumed there, while one third is exported. The most important importers of Austrian products are Italy, Germany and the Russian Federation.

Table 5.

Embodied HANPP related to grasslands, Austria 2000, breakdown by countries of origin respectively destination.

| Rank | Country | eHANPP [Mt/yr] | Share in total [%] | Cumul. share [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Origin account | ||||

| 1 | Austria | 7.71 | 85.0% | 85% |

| 2 | Germany | 0.47 | 5.2% | 90% |

| 3 | Netherlands | 0.14 | 1.5% | 92% |

| 4 | Australia | 0.09 | 1.0% | 93% |

| 5 | France | 0.09 | 1.0% | 94% |

| 6 | Thailand | 0.07 | 0.8% | 94% |

| 7 | Brazil | 0.05 | 0.6% | 95% |

| 8 | Ireland | 0.05 | 0.5% | 96% |

| 9 | UK | 0.04 | 0.4% | 96% |

| Other | 0.36 | 4.0% | 100% | |

| Total | 9.08 | 100.0% | ||

| (2) Destination account | ||||

| 1 | Austria | 7.71 | 63.7% | 64% |

| 2 | Italy | 1.54 | 12.7% | 76% |

| 3 | Germany | 0.74 | 6.1% | 83% |

| 4 | Russian Federation | 0.28 | 2.3% | 85% |

| 5 | Greece | 0.27 | 2.3% | 87% |

| 6 | France | 0.18 | 1.5% | 89% |

| 7 | Belgium | 0.14 | 1.2% | 90% |

| 8 | Netherlands | 0.14 | 1.1% | 91% |

| 9 | UK | 0.11 | 0.9% | 92% |

| Other | 0.98 | 8.1% | 100% | |

| Total | 12.11 | 100.0% | ||

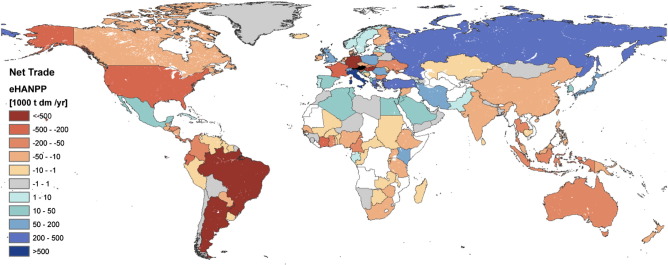

Countries that net-export product-related eHANPP to Austria are primarily new-world countries such as Brazil, the USA, Argentina, Australia, but also neighboring countries such as Germany, France or Hungary (Fig. 2). Italy is the largest recipient of Austria's net exports, followed by Old-world countries like Greece Turkey, Poland, Russia and the UK. Also countries in the Northern Africa and Western Asia region, strong net-importers of biomass products and thus eHANPP (Erb et al., 2009b) are net-importers of Austrian HANPP. In contrast, most of Sub-Saharan Africa is net-exporting eHANPP to Austria. As discussed above, import and export flows are not balanced.

Fig. 2.

Austria's net trade balance in terms of HANPP embodied in agricultural products at the bilateral level for the year 2000. Red (warm) tones show countries that supply Austria with net imports, blue (cold) tones receive net exports from Austria. White color: no data. Note the non-linear scale.

The embodied HANPP related to Austria's consumption of animal-derived food products is analyzed in Fig. 3. According to FAO (2010) data, consumption of animal products amounts to 0.9 Mt dry matter (d.m.) per year (1 Mt = 106 tons = 1012 g = 1 Tg), supplying approximately one third of the food calories available in Austria (in total 1250 kcal/cap/day). Milk products account for 38% of that total, pork for 29% and animal fat for another 16%, the remainder (17%) being ruminant meat, poultry, eggs and fish. The production of these products required 10.5 Mt d.m./yr of feed (overall feed conversion ratio of 11.8). The eHANPP related to this feed amounted to 19.7 Mt d.m./yr, that is, more than 20 times the mass of the consumed products. 75% of this total eHANPP was related to the provision of ruminant products. Per kg dry matter of product, ruminant products result in an eHANPP of 33 kg d.m., while the corresponding value for monogastric species is “only” 11 kg d.m. To put these numbers into perspective, just over 2.5 kg d.m. of eHANPP were necessary per kg d.m. of wheat based food products.

Fig. 3.

Austria's consumption of animal-based products, required feedstuff and their embodied HANPP in the year 2000.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The above-discussed results confirm the enormous importance of trade for the resource supply of industrialized countries, even for countries with an intermediate population density below 100 inhabitants per km2 such as Austria. Only about half of the eHANPP of cropland-based agricultural products consumed in Austria is originating in Austria, and about one third of the HANPP resulting from crop production on Austria's territory is embodied in products that are exported and consumed elsewhere. Moreover, while Austria's aggregate ‘import dependency’ in terms of agricultural eHANPP is relatively low (with a trade deficit of 5% of domestic consumption), both import and export flows are three times as large as this net-balance, and both are growing exponentially (Krausmann and Haberl, 2002).

Our findings underline the necessity of sound methods for environmental monitoring and reporting of trade-related relocations of environmental pressures to complement established indicators such as virtual water or carbon footprints. eHANPP can play a specific role in this context, because eHANPP allows us to consistently link resource consumption with the bioproductive capacity of ecosystems, in terms of the area of land required for production but also, and more importantly, in terms of the intensity with which terrestrial ecosystems are used. Most other indicators related to resource flows (material, energy or carbon flows as well as the ecological footprint) refer to the resource throughput of countries or, in other words, their socioeconomic metabolism (Ayres and Simonis, 1994; Fischer-Kowalski, 1998; Martinez-Alier, 1987), but do not consider ecological conditions of production. Only eHANPP assessments based on bilateral trade matrices are able to trace these flows on a country-by-country basis (Tables 2–5, Fig. 2), and only by using information on bilateral trade flows on the product level can data to evaluate individual activities such as food consumption be generated (Fig. 3).

As cross-country analysis has shown, indicators of socioeconomic metabolism are highly correlated with each other and with GDP (Haberl et al., 2012b). The same analysis has demonstrated that eHANPP is not correlated with biophysical indicators of resource throughput and GDP (Haberl et al., 2012b; Seekell et al., 2011 find similar patterns for GDP and virtual water use). Because land use is one of the major drivers of biodiversity loss (Sala et al., 2000) and a globally pervasive driver of environmental change (Foley et al., 2005; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005), it is essential to incorporate these aspects of resource use which are not well captured by indicators of socioeconomic metabolism in environmental reporting systems. Furthermore, as HANPP has been shown to be related with pressures on biodiversity (Haberl et al., 2004; Haberl et al., 2005; Haberl et al., 2009b), embodied HANPP is a promising approach to integrate biodiversity concerns in trade-related environmental information systems.

The example of animal-based food demonstrates how eHANPP can help to elucidate the environmental pressure related to complex production chains and to assess environmental pressures per unit of the final product. It shows the enormous importance of animal-related food in terms of the productive capacity of ecosystems required to generate these products. It also shows that monogastric species are more ‘efficient’ in terms of eHANPP per unit of product, although it important to keep in mind that monogastric species are to a large extent fed with biomass that could also be used to produce human food, whereas ruminants are predominantly fed on biomass that humans cannot digest (FAO, 2011).5

Another important group of products where eHANPP could play an important role in comparing the environmental pressures of different production chains are different types of bioenergy. As the use of bioproductive capacities of ecosystems is a major concern related to the environmental performance of bioenergy (Haberl et al., 2012a; Schulze et al., 2012), eHANPP could help to differentiate between more or less environmentally favorable bioenergy production and use pathways and could hence provide additional criteria to those which currently play a major role, e.g., GHG emissions from the life cycle (e.g., Cherubini et al., 2009; Sterner and Fritsche, 2011; Zanchi et al., 2012).

The eHANPP accounting method discussed here allows to consistently and systematically allocate (1) agricultural land area and (2) intensity of agricultural land use, in terms of effects on trophic energy (biomass) flows to products used. This is not only informative as a proxy for the pressures on ecosystems and biodiversity related to land use in a country,6 but also as one major step towards a method to calculate the land-use change related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions related to the biomass-based products consumed in a country. Current methods based on input–output analysis techniques to calculate the ‘carbon footprint’ of national consumption patterns only refer to the GHG emissions from fossil fuel combustion and processes such as cement manufacture, but do not include the land-use related GHG emissions (Davis and Caldeira, 2011; Hertwich and Peters, 2009; Peters and Hertwich, 2008; Peters et al., 2011). eHANPP databases such as the one presented here are a major step towards such accounts.

We conclude that eHANPP is a promising concept to evaluate the environmental pressures of process chains related to the use of bioproductive capacities of terrestrial ecosystems. It is therefore a worthwhile approach for further research into consumption-based accounting methods and consumption-based approaches towards more sustainable resource use. eHANPP can help to address some of the current ‘grand sustainability challenges’ such as climate change mitigation, biodiversity conservation and sustainable land use, in particular those related to the ‘teleconnections’ between producing and consuming regions, city–hinterland relations, ecological distribution conflicts, and unequal exchange (Hornborg, 1998; Martinez-Alier et al., 2010; Muradian and Martinez-Alier, 2001; Muradian et al., 2002; Seto et al., 2012).

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the EU-FP7 project VOLANTE (grant agreement no. 265104), by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Water and the Environment (BMLFUW, contract UW.1.4.18/0081-V/10/2010), by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), project P20812-G11 and by the Research Council (‘Forschungsrat’) of the Alpen-Adria Universitaet Klagenfurt, Wien, Graz. It contributes to the Global Land Project (http://www.globallandproject.org). We thank two anonymous reviewers for useful comments on a previous draft that have helped a lot to improve the paper.

Footnotes

Imhoff et al. (2004) did not use the notion of ‘embodied HANPP’, but their method of calculating HANPP was consumption based and conceptually similar to that of Erb et al. (2009a, 2009b) who coined the notion of ‘embodied HANPP’.

Methods based on monetary value allocate a larger share of the upstream flows to the most valuable secondary product and therefore reduce the relative weight given to byproducts. Which allocation method is most useful depends on the purpose of the study. This article is focused on demonstrating the feasibility of eHANPP accounts based on bilateral trade matrices in biophysical units. Evaluating different allocation methods is beyond the scope; for a qualitative discussion see Haberl et al. (2009a, pp. 125ff).

Changes in biomass stocks resulting from deforestation are not included in this paper due to its focus on agricultural products. They would be included in a full eHANPP account that also covers forest harvest and fires.

Inaccuracies resulting from this problem are only substantial in large countries with stronger climatic and/or soil fertility gradients. In the Austrian case, the problem would only affect imports from countries such as the USA, Brazil or Russia which are a relatively minor fraction of Austria's biomass imports. The problem may be more substantial in other countries and can be solved using maps on crop distribution, e.g. those by Monfreda et al. (2008). Doing so was beyond the scope of this study, however.

On the other hand, parts of the land now occupied by grazing or hay production could also be used for other purposes, e.g. bioenergy production (Erb et al., 2012).

Empirical studies suggest that HANPP is a useful indicator of pressures on biodiversity (Haberl et al., 2007b). Rising average HANPP in a country is also likely to result in higher HANPP levels in specific regions which might well have a negative impact on biodiversity. Spatially explicit HANPP data like those in Haberl et al.'s (2007a) are needed to further analyze such connections.

References

- Ayres R.U., Simonis U.E. United Nations University Press; Tokyo, New York, Paris: 1994. Industrial Metabolism: Restructuring for Sustainable Development. [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini F., Bird N.D., Cowie A., Jungmeier G., Schlamadinger B., Woess-Gallasch S. Energy- and greenhouse gas-based LCA of biofuel and bioenergy systems: key issues, ranges and recommendations. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2009;53:434–447. [Google Scholar]

- Davis S.J., Caldeira K. Consumption-based accounting of CO2 emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:18554–18559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906974107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb K.-H. Actual land demand of Austria 1926–2000: a variation on ecological footprint assessments. Land Use Policy. 2004;21:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Erb K.-H., Gaube V., Krausmann F., Plutzar C., Bondeau A., Haberl H. A comprehensive global 5 min resolution land-use data set for the year 2000 consistent with national census data. Journal of Land Use Science. 2007;2:191–224. [Google Scholar]

- Erb K.-H., Krausmann F., Gaube V., Gingrich S., Bondeau A., Fischer-Kowalski M., Haberl H. Analyzing the global human appropriation of net primary production — processes, trajectories, implications. An introduction. Ecological Economics. 2009;69:250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Erb K.-H., Krausmann F., Lucht W., Haberl H. Embodied HANPP: mapping the spatial disconnect between global biomass production and consumption. Ecological Economics. 2009;69:328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Erb K.-H., Haberl H., Plutzar C. Dependency of global primary bioenergy crop potentials in 2050 on food systems, yields, biodiversity conservation and political stability. Energy Policy. 2012;47:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.04.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO); Rome: 2003. Technical Conversion Factors for Agricultural Commodities. [Google Scholar]

- FAO FAOSTAT Statistical Database [WWW Document] 2010. http://faostat.fao.org/ URL.

- FAO . Livestock in Food Security. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); Rome: 2011. World Livestock 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fargione J., Hill J., Tilman D., Polasky S., Hawthorne P. Land clearing and the biofuel carbon debt. Science. 2008;319:1235–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.1152747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Kowalski M. Society's metabolism: the intellectual history of materials flow analysis, part I, 1860–1970. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 1998;2:107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Foley J.A., DeFries R., Asner G.P., Barford C., Bonan G., Carpenter S.R., Chapin F.S., Coe M.T., Daily G.C., Gibbs H.K., Helkowski J.H., Holloway T., Howard E.A., Kucharik C.J., Monfreda C., Patz J.A., Prentice I.C., Ramankutty N., Snyder P.K. Global consequences of land use. Science. 2005;309:570–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1111772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilova O., Jonas M., Erb K., Haberl H. International trade and Austria's livestock system: direct and hidden carbon emission flows associated with production and consumption of products. Ecological Economics. 2010;69:920–929. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbens-Leenes W., Hoekstra A.Y., Van Der Meer T.H. The water footprint of bioenergy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:10219–10223. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl H., Schulz N.B., Plutzar C., Erb K.H., Krausmann F., Loibl W., Moser D., Sauberer N., Weisz H., Zechmeister H.G., Zulka P. Human appropriation of net primary production and species diversity in agricultural landscapes. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 2004;102:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl H., Plutzar C., Erb K.-H., Gaube V., Pollheimer M., Schulz N.B. Human appropriation of net primary production as determinant of avifauna diversity in Austria. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 2005;110:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl H., Erb K.H., Krausmann F., Gaube V., Bondeau A., Plutzar C., Gingrich S., Lucht W., Fischer-Kowalski M. Quantifying and mapping the human appropriation of net primary production in earth's terrestrial ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:12942–12947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704243104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberl H., Erb K.-H., Plutzar C., Fischer-Kowalski M., Krausmann F. Human appropriation of net primary production (HANPP) as indicator for pressures on biodiversity. In: Hák T., Moldan B., Dahl A.L., editors. Sustainability Indicators: A Scientific Assessment. Vol. 67. Island Press; Washington, D.C., Covelo, London: 2007. pp. 271–288. (SCOPE). [Google Scholar]

- Haberl H., Erb K.-H., Krausmann F., Berecz S., Ludwiczek N., Martinez-Alier J., Musel A., Schaffartzik A. Using embodied HANPP to analyze teleconnections in the global land system: conceptual considerations. Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography. 2009;109:119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl H., Gaube V., Díaz-Delgado R., Krauze K., Neuner A., Peterseil J., Plutzar C., Singh S.J., Vadineanu A. Towards an integrated model of socioeconomic biodiversity drivers, pressures and impacts. A feasibility study based on three European long-term socio-ecological research platforms. Ecological Economics. 2009;68:1797–1812. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl H., Sprinz D., Bonazountas M., Cocco P., Desaubies Y., Henze M., Hertel O., Johnson R.K., Kastrup U., Laconte P., Lange E., Novak P., Paavola J., Reenberg A., van den Hove S., Vermeire T., Wadhams P., Searchinger T. Correcting a fundamental error in greenhouse gas accounting related to bioenergy. Energy Policy. 2012;45:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberl H., Steinberger J.K., Plutzar C., Erb K.-H., Gaube V., Gingrich S., Krausmann F. Natural and socioeconomic determinants of the embodied human appropriation of net primary production and its relation to other resource use indicators. Ecological Indicators. 2012;23:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haes H.U., Heijungs R., Huppes G., Voet E., Hettelingh J. Full mode and attribution mode in environmental analysis. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 2000;4:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwich E.G., Peters G.P. Carbon footprint of nations: a global, trade-linked analysis. Environmental Science & Technology. 2009;43:6414–6420. doi: 10.1021/es803496a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra A.Y., Hung P.Q. Globalisation of water resources: international virtual water flows in relation to crop trade. Global Environmental Change. 2005;15:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hornborg A. Towards an ecological theory of unequal exchange: articulating world system theory and ecological economics. Ecological Economics. 1998;25:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hornborg A., Jorgenson A.K., editors. International Trade and Environmental Justice: Toward a Global Political Ecology. Nova Science Pub Inc.; Hauppauge, New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Imhoff M.L., Bounoua L., Ricketts T., Loucks C., Harriss R., Lawrence W.T. Global patterns in human consumption of net primary production. Nature. 2004;429:870–873. doi: 10.1038/nature02619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmeier G., Werner F., Jarnehammar A., Hohenthal C., Richter K. Allocation in LCA of wood-based products experiences of cost action E9 part I. methodology. International Journal of Life Cycle Analysis. 2002;7:290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner T., Erb K.-H., Nonhebel S. International wood trade and forest change: a global analysis. Global Environmental Change. 2011;21:947–956. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner T., Kastner M., Nonhebel S. Tracing distant environmental impacts of agricultural products from a consumer perspective. Ecological Economics. 2011;70:1032–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Krausmann F., Haberl H. The process of industrialization from the perspective of energetic metabolism: socioeconomic energy flows in Austria 1830–1995. Ecological Economics. 2002;41:177–201. [Google Scholar]

- Krausmann F., Erb K.-H., Gingrich S., Lauk C., Haberl H. Global patterns of socioeconomic biomass flows in the year 2000: a comprehensive assessment of supply, consumption and constraints. Ecological Economics. 2008;65:471–487. [Google Scholar]

- Lauk C., Erb K.-H. Biomass consumed in anthropogenic vegetation fires: global patterns and processes. Ecological Economics. 2009;69:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen M., Moran D., Kanemoto K., Foran B., Lobefaro L., Geschke A. International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature. 2012;486:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature11145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Alier J. Energy, Environment and Society. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 1987. Ecological economics. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Alier J., Kallis G., Veuthey S., Walter M., Temper L. Social metabolism, ecological distribution conflicts, and valuation languages. Ecological Economics. 2010;70:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment . Island Press; Washington, D.C.: 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- Monfreda C., Ramankutty N., Foley J.A. Farming the planet: 2. Geographic distribution of crop areas, yields, physiological types, and net primary production in the year 2000. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 2008;22 [Google Scholar]

- Muradian R., Martinez-Alier J. Trade and the environment: from a “Southern” perspective. Ecological Economics. 2001;36:281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Muradian R., O'Connor M., Martinez-Alier J. Embodied pollution in trade: estimating the “environmental load displacement” of industrialised countries. Ecological Economics. 2002;41:51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Peters G.P., Hertwich E.G. CO2 embodied in international trade with implications for global climate policy. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008;42:1401–1407. doi: 10.1021/es072023k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters G.P., Minx J.C., Weber C.L., Edenhofer O. Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:8903–8908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006388108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebitzer G., Ekvall T., Frischknecht R., Hunkeler D., Norris G., Rydberg T., Schmidt W.-P., Suh S., Weidema B.P., Pennington D.W. Life cycle assessment: part 1: framework, goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, and applications. Environment International. 2004;30:701–720. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala O.E., Chapin F.S., Armesto J.J., Berlow E., Bloomfield J., Dirzo R., Huber-Sanwald E., Huenneke L.F., Jackson R.B., Kinzig A., Leemans R., Lodge D.M., Mooney H.A., Oesterheld M., Poff N.L., Sykes M.T., Walker B.H., Walker M., Wall D.H. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science. 2000;287:1770–1774. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze E., Körner C., Law B.E., Haberl H., Luyssaert S. Large-scale bioenergy from additional harvest of forest biomass is neither sustainable nor greenhouse gas neutral. GCB Bioenergy. 2012;4(6):611–616. [Google Scholar]

- Searchinger T., Heimlich R., Houghton R.A., Dong F., Elobeid A., Fabiosa J., Tokgoz S., Hayes D., Yu T.-H. Use of U.S. croplands for biofuels increases greenhouse gases through emissions from land-use change. Science. 2008;319:1238–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1151861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seekell D.A., D'Odorico P., Pace M.L. Virtual water transfers unlikely to redress inequality in global water use. Environmental Research Letters. 2011;6:024017. [Google Scholar]

- Seto K.C., Reenberg A., Boone C.G., Fragkias M., Haase D., Langanke T., Marcotullio P., Munroe D.K., Olah B., Simon D. Urban land teleconnections and sustainability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:7687–7692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117622109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen W. The arctic in an earth system context: from brake to accelerator of change. Ambio. 2006;35:153–159. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2006)35[153:taiaes]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner M., Fritsche U. Greenhouse gas balances and mitigation costs of 70 modern Germany-focused and 4 traditional biomass pathways including land-use change effects. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2011;35:4797–4814. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bergh J.C.J., Verbruggen H. Spatial sustainability, trade and indicators: an evaluation of the “ecological footprint”. Ecological Economics. 1999;29:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek P.M., Ehrlich P.R., Ehrlich A.H., Matson P.A. Human appropriation of the products of photosynthesis. Bioscience. 1986;36:363–373. [Google Scholar]

- Weidema B. Avoiding co-product allocation in life-cycle assessment. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 2000;4:11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wright D.H. Human impacts on the energy flow through natural ecosystems, and implications for species endangerment. Ambio. 1990;19:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Zanchi G., Pena N., Bird N. Is woody bioenergy carbon neutral? A comparative assessment of emissions from consumption of woody bioenergy and fossil fuel. GCB Bioenergy. 2012 [Google Scholar]