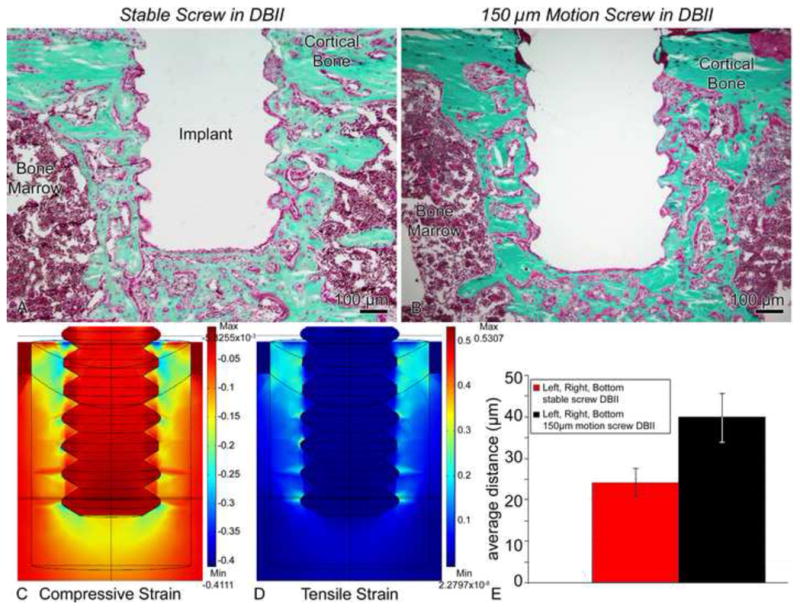

Figure 10.

Light micrographs of (A) stable (group 7) and (B) screws moving 150 μm (group 8) in a direct-bone-implant-interface (DBII). A difference in the shape and orientation of the threads of loaded implants can be observed in implants subjected to micromotion (B). (C, D) Finite element analyses predicted very large (i.e., 30–100%) tensile (C) and compressive (D) principal strain magnitudes at screw thread tips and beneath the screw in this DBII. Due to expected damage from drilling etc., we used a Young’s elastic modulus for the bone adjacent to the implant that was 70% of the largest value that we measured in the healing interface, i.e., we used 11.9 MPa (= 0.7 × 17 MPa). (E) There was a significantly larger bone-implant distance for motion cases vs. stable, which correlated with the localization of these large strains (95% confidence interval).