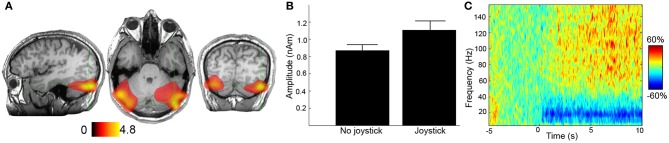

Figure 2.

Example of muscle artifacts in MEG data. In this task (Kennedy et al., 2011), participants are asked to either track a moving object on screen with a joystick or simply observe the moving object. (A) The difference in 50–100 Hz source power is presented for the joystick and no-joystick conditions for a single participant. Units are pseudo t-values. (B) Peak-source amplitudes for the two conditions for the right hand source location. Based on panels (A) and (B) it would be tempting to speculate that tracking with the joystick has caused an increase in high-frequency activity in the bilateral cerebellar cortices; however, in panel (C) the reconstructed time-frequency spectrum is presented (10 s of tracking, baselined to 5 s of rest—units are percentage change from baseline). It is immediately apparent that there is broad bandwidth of the high-frequency activity in this virtual sensor. It is highly likely that this was caused by the increased postural activity of upper neck muscles, caused by the manipulation of the joystick. The lower-frequency beta-band desynchronization may represent a true difference in brain activity. This virtual sensor therefore contains a mixture of both brain and non-brain activity due to imperfect spatial filtering. Note: these data were recorded at 600 Hz with an anti-aliasing filter set at 150 Hz, the maximum frequency displayed here. Ideally, these data would have been sampled at a higher frequency to capture more bandwidth of the response. Recording of electromyograms from the neck muscles would also have been useful.