Abstract

Objectives

There is limited literature on acute pancreatitis (AP), acute recurrent pancreatitis (ARP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP) in children. The INSPPIRE (International Study group of Pediatric Pancreatitis: In search for a cure) consortium was formed to standardize definitions, develop diagnostic algorithms, investigate disease pathophysiology and design prospective multicenter studies in pediatric pancreatitis.

Methods

Subcommittees were formed to delineate definitions of pancreatitis and a survey was conducted to analyze current practice.

Results

Acute pancreatitis (AP) was defined as requiring 2 of: (1) abdominal pain compatible with AP, (2) serum amylase and/or lipase values ≥3 times upper limits of normal, (3) imaging findings of AP. ARP was defined as: ≥2 distinct episodes of AP with intervening return to baseline. CP was diagnosed in the presence of: (1) typical abdominal pain plus characteristic imaging findings or; (2) exocrine insufficiency plus imaging findings or; (3) endocrine insufficiency plus imaging findings. We found that children with pancreatitis were primarily managed by pediatric gastroenterologists. Unless the etiology was known, initial investigations included serum liver enzymes, triglycerides, calcium, and abdominal ultrasound. Further investigations (usually for ARP and CP) included magnetic resonance or other imaging, sweat chloride, and genetic testing. Respondents’ future goals for INSPPIRE included: (1) determining natural history of pancreatitis; (2) eveloping algorithms to evaluate and manage pancreatitis; and (3) validating diagnostic criteria.

Conclusions

INSPPIRE represents the first initiative to create a multicenter approach to systematically characterize pancreatitis in children. Future aims include creation of patient database and biologic sample repository.

Keywords: pediatrics, acute pancreatitis, acute recurrent pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, definitions, practice parameters

INTRODUCTION

Publications from the past few decades describe an increasing incidence of acute pancreatitis (AP) in both children and adults (1–3) adults. This may represent a true rise in the incidence of pediatric pancreatitis or other factors such as improved awareness of the condition (4–6). The prevalence of acute pancreatitis in adults ranges between 6–45/100,000 person-years in various populations and ages, with lesser rates reported in younger patients (1, 2, 7). Two studies estimated the incidence of pancreatitis at 3.6 and 13.2 cases per 100,000 children (8, 9) children. The latter number is in the range of the incidence for pancreatitis in adults confirming that the pancreatitis is not a rare disease in children (10).

There is limited literature regarding acute recurrent pancreatitis (ARP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP) in children. The epidemiology and the natural history of pediatric ARP and CP are not well-understood, and there are no evidence-based diagnostic, prognostic and treatment guidelines for these disorders. Consequently, pediatric specialists often rely on diagnostic, prognostic and treatment guidelines that have been derived from adults. This is problematic, because the etiologies of pancreatitis in children are markedly different from adults, and all prognostic algorithms and therapeutic guidelines fail to consider the unique age-related requirements of childhood. For instance, major factors implicated in chronic pancreatitis in adults include alcohol use and cigarette smoking, confounders that are rarely found in children (11–15). Because childhood-onset ARP and CP are relatively uncommon, efforts to ascertain retrospective clinical data from single-institutions have failed to advance the field of knowledge concerning the incidence, natural history, morbidity and mortality of these conditions. Furthermore, there have been no multicenter clinical trials in children. To advance our current understanding of ARP and CP, we formed a consortium named INSPPIRE (International Study Group of Pediatric Pancreatitis: In Search for a Cure). Current members of the consortium include gastroenterologists with an interest in pancreatitis as well as individuals from related disciplines (please refer to the Acknowledgments section).

The first objectives of the consortium were to: (a) develop a consensus statement on the definitions of childhood-onset AP, ARP and CP with the goal of accurately phenotyping children for future studies; (b) survey pediatric gastroenterologists with an interest in pancreatitis in order to estimate the prevalence of AP, ARP and CP and to obtain data on current clinical practice concerning diagnostic evaluation and management. Respondents were also asked to list their top research priorities. The eventual goal was to develop a database of children with ARP and CP and to understand the epidemiology, etiologies, natural history and outcome in a well-phenotyped cohort of children with ARP and CP.

METHODS

1. Diagnostic Definitions

A subcommittee (VM [chair], RH, JP, SW) was formed in the summer of 2010. The goals of the sub-committee were to: (a) review available literature for consensus definitions of AP, ARP, and CP (16–18) CP; (b) develop a draft document for circulation to other members of the INSPPIRE group during the fall of 2010; (c) draft a revised document to achieve final consensus at the INSPPIRE meetings in December 2010 and May 2011. The goal of the subcommittee was to develop the definitions that would accurately classify children with pancreatitis, thus create a homogenous population that could be easily phenotyped and included in future prospective studies.

2. Clinical Survey

A sub-committee (SH [chair], BB, MW, RA, and HB) was formed in the summer of 2010. The goals of the sub-committee were to develop a survey to determine the demographic features of the respondents, their current practice patterns and to ascertain data on the number of children with AP, ARP, and CP seen at each institution. Practice patterns were determined by developing clinical vignettes that were designed to reflect many of the diagnostic, etiologic and therapeutic challenges relating to ARP and CP (see the online-only Appendix for the survey questionnaire, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A105). The survey protocol was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) (STU 092010-223). The internet-based survey instrument SurveyMonkey (Palo Alto, CA) was utilized for survey enrollment. Pediatric gastroenterologists within INSPPIRE (21 total) were invited to complete the survey in late 2010.

RESULTS

A. Diagnostic Definitions

The definitions for pediatric AP, ARP, and CP are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of Pancreatitis in Children

| Entity | Clinical Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute Pancreatitis (AP) | Requires at least 2 out of 3 criteria:

|

| Pediatric Onset | First episode of AP occurring before the patient’s 19th birthday |

| Acute Recurrent Pancreatitis (ARP) | Requires at least 2 distinct episodes of AP (each as defined above), along with:

|

| Chronic Pancreatitis (CP) | Requires at least 1 of the following 3:

|

OR

|

Legend/Notes:

please also refer to text

- U/S: transabdominal ultrasonography’ CECT: contrast-enhanced computerized tomography; EUS: endoscopic ultrasonography; MRI/ MRCP (magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography).

-

* “Suggestive” imaging findings of chronic pancreatitis”/chronic pancreatic damage including:

- Ductal changes: irregular contour of the main pancreatic duct or its radicles; intraductal filling defects; calculi, stricture or dilation;

- Parenchymal changes: generalized or focal enlargement, irregular contour (accentuated lobular architexture), cavities, calcifications, heterogeneous echotexture

Imaging modalities may include CT, MRI/ MRCP, ERCP; U/S; EUS (in which at least 5 EUS features (as defined by the Rosemont Classification (21) must be fulfilled) - ^ “Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency” to be diagnosed via: fecal elastase-1 monoclonal assay < 100 mcg/g stool (2 separate samples done ≥1 month apart); or coefficient of dietary fat absorption < 90% on a 72-hr fecal fat collection. Neither test should be performed during an acute pancreatitis episode, as the results may be temporarily low. Children with classic cystic fibrosis, exhibiting early-onset pancreatic insufficiency without prior evidence of any meaningful pancreas sufficiency, typically should not be diagnosed with CP. They do not have chronic abdominal pain and pancreatic imaging findings described in the CP criteria.

- + “Endocrine pancreatic insufficiency” to be diagnosed via: 2006 WHO criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/ L (126 mg/dL) or plasma glucose ≥ 11.1mmol/L (200 mg/dL) 2 hours after glucose load 1.75g/kg children (to maximum 75g glucose load) (31).

Acute Pancreatitis (AP)

We would like to emphasize that abdominal pain associated with AP may be vague in children and may not radiate to the back. Lipase elevations may be a more sensitive finding in younger children, although either lipase and/or amylase elevation may be observed. While recommended imaging modalities are similar to those utilized for adult patients, pediatric experts are more likely to: (a) select tests that limit radiation exposure (i.e. transabdominal ultrasonography) and (b) recognize that certain modalities may be more difficult to perform because of patient size and sedation needs (e.g. endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)).

Imaging features compatible with AP include: pancreatic edema, pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis, peripancreatic inflammation, acute fluid collections, pancreatic hemorrhage, pancreatic abscess, and pancreatic pseudocyst (signifying a recent AP episode).

Although imaging is not necessary as part of the diagnostic work-up for AP if the other 2 criteria are fulfilled, transabdominal ultrasonography (U/S) is frequently used to rule out an obstructive etiology (choledochal cyst, traumatic injury, tumor, stones etc). Imaging is frequently normal in AP as the U/S is the imaging modality of choice in most pediatric cases (5).

Acute Recurrent Pancreatitis (ARP)

We propose that the term ARP be used instead of recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) to avoid confusion with the same abbreviation, RAP, which is commonly used by pediatricians to describe “recurrent abdominal pain”. An important exclusion would include a child who, following an episode of AP, presented with recurrence of pain and imaging showing a well-formed pseudocyst. The presence of a pseudocyst would suggest a complication arising from the first episode of pancreatitis rather than a new episode.

Chronic Pancreatitis (CP)

Chronic pancreatitis, histopathologically defined in the same manner as in adults, consists of an inflammatory process characterized by irreversible morphologic changes and fibrotic replacement of the pancreatic parenchyma. In CP, fibrosis and ductal obstruction may give rise to radiographically evident calcifications and pancreatic duct irregularities such as strictures and dilations, or histologic evidence of sclerosis/ fibrosis, acinar and islet cell loss, inflammatory infiltrates, pancreatic duct abnormalities/ scarring, and intraductal calculi (19, 20). Since a histopathological diagnosis of pediatric onset CP is rare due to the risks of performing a pancreatic biopsy, clinical criteria are considered more pragmatic for defining CP (12, 20–22). However, should a surgical resection specimen or biopsy be available, CP could be diagnosed based on compatible findings.

Importantly, children potentially could present with features diagnostic of CP without having had a prior diagnosis of AP. Abdominal pain in CP may be variably described by children; therefore, imaging characteristic of chronic pancreatic damage in conjunction with chronic abdominal pain symptoms fulfills diagnostic criteria for CP. Children with classic exocrine pancreatic insufficiency due to cystic fibrosis typically should not be diagnosed with CP.

B. Clinical Survey

A 91% response rate was achieved for the internet-based survey, which included 19 of the 21 eligible members (17 attending gastroenterologists and 2 pediatric gastroenterology trainees). Only 16 members representing the most senior attending gastroenterologists from 16 different institutions were included in the final analysis. The majority were physicians practicing in the United States (75%), who represented all geographic regions. Sixty-three percent had been practicing pediatric gastroenterology for over 10 years. All physicians practiced at either tertiary or quaternary academic centers.

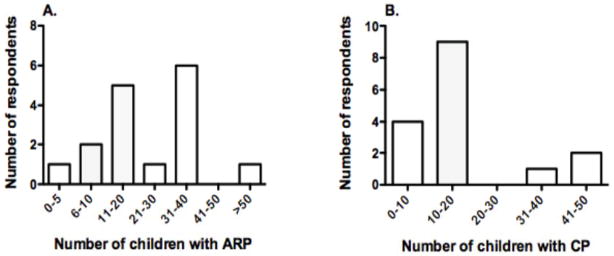

Approximately two-thirds of respondents felt that the number of admissions for AP has increased in the prior three years at their respective institutions. Half of the group (56%) estimated that they managed over 40 children with AP each year at their institution, and about one-fifth (19%) reported that they followed over 100 patients per year. Most (69%) managed only 1–3 cases of severe AP per year. Considering patients with ARP, the majority of respondents were split between seeing 11 to 20 children per year (31%) or 31 to 40 children per year (38%) (Figure 1A). The majority of physicians (56%) followed 11 to 20 outpatients with CP at their institution. (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. INSPPIRE Survey-Demographics.

Respondents were asked to estimate the number of children they followed at their institution with (A) ARP, and (B) CP. Results show the number of children with ARP and CP that are seen by the respondents.

Pediatric gastroenterologists participated primarily in the care of children with pancreatitis. Respondents were more likely to be involved in the management of children with ARP (89%) and CP (94%), than those presenting with AP (63%).

There was general agreement on most of the practice parameters for AP and ARP. Severe AP was defined as pancreatitis leading to multi-organ dysfunction, pancreatic necrosis, or death. Bowel rest and intravenous fluids were the initial management for AP (81% of mild AP vs. 75% of severe AP, while 18% instituted total parenteral nutrition). Resolution of abdominal pain was the most important factor in deciding when to begin oral feedings (50% of respondents). Forty-four percent of participants would “often” use enteral tube feedings in the course of AP management. Morphine or related opioid drugs were the medications of choice for pain control in AP (94%). Seventy-five percent provided narcotics for CP-associated pain, with (50%) or without (25%) centrally-acting agents, such as gabapentin. Sixty-nine percent of respondents “often” or “always” referred children with CP to a pain clinic or pain specialist.

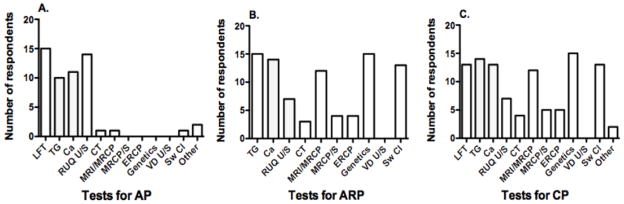

Most respondents (63%) stated that their routine evaluation of a child presenting with AP of unclear etiology and lacking a family history of pancreatitis included liver enzymes, serum triglycerides and calcium levels, as well as an abdominal ultrasound (Figure 2). Sixty-nine percent of the respondents reserved other imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP) as well as genetic testing or sweat chloride to children presenting with ARP or CP without a clear etiology or family history of pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer. Ninety-four percent of respondents would order genetic testing for PRSS1 (cationic trypsinogen), SPINK1 (serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1), and CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) mutations to evaluate for the etiology of ARP or CP, irrespective of the age of presentation. All of the practitioners had access to advanced endoscopic procedures as necessary (e.g. ERCP and/or EUS), although most respondents (88%) relied on the expertise of adult gastroenterology colleagues to perform these procedures.

Figure 2. INSPPIRE Survey-Diagnostics.

Respondents were presented with clinical case scenarios and asked to choose within a list of suggested investigations for: (A) single episode mild AP without known etiology or family history of pancreatitis; (B) ARP (2 episodes within 1 year) without known etiology or family history of pancreatitis; and (C) CP without known etiology or family history of pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer. LFT: liver function tests; TG: serum triglycerides; Ca: serum calcium; RUQ U/S: right upper quadrant ultrasound; CT: computerized tomography; MRI/MRCP: magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; MRCP/S: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography with secretin; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; genetics: gene testing for PRSS1, SPINK1, CFTR mutations; VD U/S: vas deferens ultrasound; Sw Cl: sweat chloride.

All of the participants measured fecal elastase levels in order to diagnose or monitor for pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, while 44% also performed a 3-day stool collection for fecal fat analysis. A minority of the respondents routinely evaluated exocrine function further via endoscopic pancreatic function testing including secretin stimulation +/- cholecystokinin stimulation, stool chymotrypsin, serum trypsinogen, or serum levels of fat-soluble vitamins.

The three main goals the group identified for future investigation were: (1) to determine the natural history (clinical course and outcome) of children with acute and chronic pancreatitis; (2) to develop algorithms for diagnosing, evaluating and managing patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis; (3) to establish and validate diagnostic criteria for acute and chronic pancreatitis in children. Other important goals included determining the optimal imaging for diagnosis, standardizing the assignment of etiologies, identifying gene mutations in children with “idiopathic” ARP, and predicting clinical outcomes following an acute episode of pancreatitis.

DISCUSSION

In this study we highlighted the following observations: 1) pancreatitis (acute, recurrent acute and chronic) is an emerging problem in pediatrics; 2) there are no established diagnostic criteria and evidence-based therapeutic options for children with pancreatitis; 3) due to limited numbers of children with pancreatitis at a single center, a multicenter effort is needed to establish a well-phenotyped cohort of children in order to understand the etiology and natural history of ARP and CP and to design therapeutic trials.

The constitution of INSPPIRE represents the first initiative to create a multi-center approach to systematically characterize pancreatitis in children. Our consortium is geographically diverse and includes nationally and internationally recognized pancreatologists as well as young and mid-career members who are developing pediatric pancreatology as their focus. The efforts described in this manuscript represent the first attempt of our group to formalize standard definitions of AP, ARP and CP in children that will be utilized in future research efforts and to document the current status of practice patterns in pediatric pancreatitis. We also identified the most important questions in pediatric pancreatitis as we continue our efforts to develop a database of children with ARP and CP to understand the epidemiology, etiologies, natural history and outcome of these diseases.

Our efforts parallel a multicenter effort of adult patients with pancreatitis, the North American Pancreatitis Study 2 (NAPS2) (23). Constitution of NAPS2 has led to better understanding the epidemiology, etiology and outcomes of pancreatitis in adult patients. We anticipate that INSPPIRE will achieve similar results in pediatric pancreatitis.

This is the first study describing the definitions of AP, ARP and CP in pediatric patients. We acknowledge that these definitions are based on the sparse pediatric literature and expert opinions mostly derived from adult studies. The use of expert opinion has clear limitations, since it is based on personal experience rather than scientific scrutiny. Because there is such a paucity of literature and lack of currently well-accepted standards, the opinion from a group of experts is the best first step to developing a standardized practice. As we continue our investigations on pediatric pancreatitis, we anticipate that these diagnostic criteria will require refinement.

There were several limitations of our clinical survey. First, we had a small sample size. However, the respondents were all experts and clinicians with a clinical interest in the field of pediatric pancreatitis, and the response rate was excellent (91%). Second, the survey was based on recollection and not actual database reviews; hence, there was the possibility of recall bias. Third, because the data were taken from tertiary and quaternary care centers, we may not have captured the management of children followed at community-based hospitals. The number of patients followed at primary care facilities will probably be small, as children with ARP and CP are typically referred to the tertiary care centers for consultation or further testing. Nevertheless, future studies will include children with ARP and CP followed at primary and secondary care facilities. However, in spite of the limitations, the general patterns of care and numbers of cases can be used to guide future work.

The results of this survey offered insights into how pediatric pancreatitis practice differs from adult practice. For example, there was infrequent use of invasive work-ups (e.g. ERCP, EUS) as first-line testing. By contrast, ultrasonography was used in the initial presentation more commonly than computed tomography (CT) scanning in order to limit radiation exposure. Magnetic resonance imaging/MRCP was frequently performed in cases of pediatric ARP and CP, emphasizing its importance in the investigation of anatomical abnormalities. Based on our study and the current practice, ultrasound and MRCP should be considered to exclude anatomical abnormalities in children with ARP and CP.

Pediatric specialists rarely ordered enteral tube feedings in cases of AP, even though “early” enteral tube feeding is recommended in the management of severe AP in adults (24–27). Pancreatic stimulation tests were also rarely used for the diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in children, INSPPIRE members tended to use fecal elastase measurements instead.

There are limited data on the etiology and diagnostic testing of ARP and CP in children (28, 29). Our survey represents the first multicenter effort to describe the practice patterns at institutions that evaluate and treat children with ARP and CP. We have demonstrated that most experts are relatively conservative with the work-up of a single episode of AP, but detailed investigation is implemented once a child presents with ARP or CP. Based on our study, we are currently unable to make solid recommendations for the diagnostic testing of ARP and CP, nor are we able to comment on the reliability of diagnostic techniques used for the assessment of exocrine pancreatic function. This will be the focus of future studies.

A larger multi-center sample of properly phenotyped and subsequently genotyped pediatric pancreatitis patients will help determine appropriate testing and optimal management while limiting unnecessary tests and interventions. Health-related quality of life measurements of this pediatric population may also be beneficial to determine if medical management is optimal (30).

In summary, the INSPPIRE Consortium is the first multicenter effort to overcome the barriers that have hampered progress in the field of pediatric pancreatology and to develop evidence-based therapies for pediatric patients with ARP and CP. In this manuscript, we described the definitions of acute pancreatitis, acute recurrent pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis. We also reported the demographics and the clinical practice patterns of pediatric pancreatitis and identified the most important questions for prospective studies. Future plans of INSPPIRE include working on the priorities identified by the group through well-designed, multicenter research collaborations, including the development of diagnostic and management algorithms, understanding the etiology, epidemiology and natural history of ARP and CP in children and investigating whether functional alterations in CFTR, PRSS1, SPINK1 or other modifier genes contribute to the presence and severity of pediatric pancreatitis. The creation of a database and a bio-repository of children with ARP and CP will be a crucial step to answering these questions.

Acknowledgments

INSPIRRE members 2010–2011: Maisam Abu-Al-Haija, Rabea Alhosh, Harrison Bai, Bradley Barth, Melena Bellin, Pam Brown, Peter Durie, Douglas Fishman, Steven Freedman, Cheryl Gariepy, Matthew Giefer, Jeff Goldsmith, Tanja Gonska, Julia Greer, Ryan Himes, Sohail Husain, Mel Hyman, Daina Kalnins, Soma Kumar, James Lopez, Mark Lowe, Alan Mayer, Veronique Morinville, Keith Ooi, John Pohl, Alexandra Quittner, Sarah Jane Schwarzenberg, Aliye Uc, James Varni, Narayanan Venkatasubramini, Michael Wilschanski, Steven Werlin.

Definitions subcommittee: Veronique Morinville (VM, chair); Ryan Himes (RH); John Pohl (JP), Steven Werlin (SW).

Survey subcommittee: Sohail Husain (SH, chair); Harrison X. Bai (HB), Bradley Barth (BB), Michael Wilschanski (MW), Rabea Alhosh (RA).

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jpgn.org).

References

- 1.Satoh K, Shimosegawa T, Masamune A, et al. Nationwide epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2011;40:503–7. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318214812b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2006;33:323–330. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000236733.31617.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joergensen M, Brusgaard K, Cruger DG. Incidence, prevalence, etiology, and prognosis of first-time chronic pancreatitis in young patients: a nationwide cohort study. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2988–98. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai HX, Lowe ME, Husain SZ. What have we learned about acute pancreatitis in children? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:262–70. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182061d75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park A, Latif SU, Shah AU, et al. Changing referral trends of acute pancreatitis in children: A 12-year single-center analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:316–322. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818d7db3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morinville VD, Barmada MM, Lowe ME. Increasing incidence of acute pancreatitis at an American pediatric tertiary care center: is greater awareness among physicians responsible? Pancreas. 2010;39:5–8. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181baac47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen HN, Lu CL. Incidence, resource use, and outcome of acute pancreatitis with/without intensive care: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Pancreas. 2011;40:10–5. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f7e750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keim V, Witt H, Bauer N, et al. The course of genetically determined chronic pancreatitis. JOP. 2003;4:146–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebours V, Boutron-Ruault MC, Schnee M, et al. The natural history of hereditary pancreatitis: a national series. Gut. 2009;58:97–103. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.149179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corfield AP, Cooper MJ, Williamson RC. Acute pancreatitis: a lethal disease of increasing incidence. Gut. 1985;26:724–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.7.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sajith KG, Chacko A, Dutta AK. Recurrent acute pancreatitis: clinical profile and an approach to diagnosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3610–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMagno MJ, DiMagno EP. Chronic pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:490–8. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833d11b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Haddad M, Wallace MB. Diagnostic approach to patients with acute idiopathic and recurrent pancreatitis, what should be done? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1007–10. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitcomb DC. Genetic aspects of pancreatitis. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:413–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.041608.121416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:682–707. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romagnuolo J, Guda N, Freeman M, et al. Preferred designs, outcomes, and analysis strategies for treatment trials in idiopathic recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:966–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nievelstein RA, Robben SG, Blickman JG. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic imaging in children-techniques and an overview of non-neoplastic disease entities. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:55–75. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1858-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trout AT, Elsayes KM, Ellis JH, et al. Imaging of acute pancreatitis: prognostic value of computed tomographic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34:485–95. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181d344ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behrman SW, Fowler ES. Pathophysiology of chronic pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:1309–24. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchler MW, Martignoni ME, Friess H, et al. A proposal for a new clinical classification of chronic pancreatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catalano MF, Sahai A, Levy M, et al. EUS-based criteria for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis: the Rosemont classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1251–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasbrenner B, Kahl S, Malfertheiner P. Modern diagnostics of chronic pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:935–41. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitcomb DC, Yadav D, Adam S, et al. Multicenter approach to recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis in the United States: the North American Pancreatitis Study 2 (NAPS2) Pancreatology. 2008;8:520–31. doi: 10.1159/000152001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegazi R, Raina A, Graham T, et al. Early jejunal feeding initiation and clinical outcomes in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:91–6. doi: 10.1177/0148607110376196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A, Singh N, Prakash S, et al. Early enteral nutrition in severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing nasojejunal and nasogastric routes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:431–34. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200605000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh N, Sharma B, Sharma M, et al. Evaluation of Early Enteral Feeding Through Nasogastric and Nasojejunal Tube in Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Noninferiority Randomized Controlled Trial. Pancreas. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318221c4a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrov MS, Correia MI, Windsor JA. Nasogastric tube feeding in predicted severe acute pancreatitis. A systematic review of the literature to determine safety and tolerance. JOP. 2008;9:440–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez-Ramirez CA, Larrosa-Haro A, Flores-Martinez S, et al. Acute and recurrent pancreatitis in children: etiological factors. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:534–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucidi V, Alghisi F, Dall’Oglio L, et al. The etiology of acute recurrent pancreatitis in children: a challenge for pediatricians. Pancreas. 2011;40:517–21. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318214fe42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pohl JF, Limbers CA, Kay M, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Pediatric Patients with Long-Standing Pancreatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182407c4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–97. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]