Abstract

Objective

HIV infection and illicit drug use are each associated with diminished cognitive performance. This study examined the separate and interactive effects of HIV and recent illicit drug use on verbal memory, processing speed and executive function in the multicenter Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS).

Methods

Participants included 952 HIV-infected and 443 HIV-uninfected women (mean age=42.8, 64% African-American). Outcome measures included the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised (HVLT-R) and the Stroop test. Three drug use groups were compared: recent illicit drug users (cocaine or heroin use in past 6 months, n=140), former users (lifetime cocaine or heroin use but not in past 6 months, n=651), and non-users (no lifetime use of cocaine or heroin, n=604).

Results

The typical pattern of recent drug use was daily or weekly smoking of crack cocaine. HIV infection and recent illicit drug use were each associated with worse verbal learning and memory (p's<.05). Importantly, there was an interaction between HIV serostatus and recent illicit drug use such that recent illicit drug use (compared to non-use) negatively impacted verbal learning and memory only in HIV-infected women (p's <0.01). There was no interaction between HIV serostatus and illicit drug use on processing speed or executive function on the Stroop test.

Conclusion

The interaction between HIV serostatus and recent illicit drug use on verbal learning and memory suggests a potential synergistic neurotoxicity that may affect the neural circuitry underlying performance on these tasks.

INTRODUCTION

Despite improved cognitive outcomes following the introduction of combination anti-retroviral therapy (cART), HIV-infected individuals continue to show cognitive impairment, particularly in verbal episodic memory and executive function1. Episodic memory is impaired in up to 50% of HIV-infected individuals2, and these cognitive deficits predict daily functioning3–5. HIV-associated deficits in verbal memory are characterized by deficits in executive control of encoding and retrieval mechanisms6–8, a pattern consistent with a frontal-subcortical involvement. Dependence on illicit drugs is also consistently associated with deficits in cognitive function, including verbal memory9–14 and executive function15–18. Given that the use of illicit substances is common in HIV-infected populations, it is important to understand how HIV-infection and illicit drug use might interact to impact cognitive function.

A number of recent in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that cocaine directly affects the neuropathogenesis of HIV19–31. Cocaine amplifies HIV replication21,22,25,28,30, including in human astrocytes29, which can function as cellular reservoirs for HIV in the brain32. Cocaine may also increase HIV-infected monocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier23,24. Cocaine enhances the neurotoxic effects of the HIV viral protein Tat19,20,26,27,31. Similarly, opiates increase neurotoxicity of HIV proteins Tat33–35 and gp12035. Importantly, cocaine and opiates, in combination with HIV proteins, negatively impact hippocampal neurogenesis36. Given that the hippocampus is critical for episodic memory, translation of these preclinical findings into clinical studies may lend important new insights into memory function in HIV-infected cocaine users.

Although many studies have investigated the impact of illicit drug use on HIV disease progression, the effects of cocaine and heroin use on cognition in HIV-infected women have not been elucidated37. Such studies are critical in light of the myriad sex differences in illicit substance use disorders. Women have higher current and lifetime use of cocaine and are more likely than men to become cocaine-dependent38–40. Women who use cocaine are three times more likely to become infected with HIV than women who do not use cocaine41. Cocaine use is also associated with accelerated disease progression in women with HIV, even when statistically controlling for anti-retroviral therapy use42,43 and medication adherence44. For example, in the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), HIV-infected women who used crack cocaine were three times more likely to die of AIDS-related causes than women who did not use crack cocaine, even when controlling for adherence to highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART)44. Studies of illicit drug use in women generally have not found an effect of opiates on HIV disease progression43,45.

Our aim was to investigate the impact of HIV infection and illicit drug use on cognition in women. We compared three categories of drug use: recent use, former use, and non-use. Primary outcomes were measures of verbal learning and memory, processing speed, and executive function based on neuropsychological tests with demonstrated sensitivity to HIV-related neurocognitive dysfunction46–50. We hypothesized that HIV and illicit drug use, especially cocaine use, would have an interactive effect on verbal learning and memory and executive function.

METHOD

Subjects

All participants were enrolled in the WIHS, the largest prospective, longitudinal, multi-center study of HIV progression in women51,52. Study methodology, standardized data collection, and training of interviewers have been previously reported51,52. We analyzed cross-sectional data from 947 HIV-infected and 443 HIV-uninfected control participants (mean age=42.8, 64% African-American). The data were collected as part of a study of menopause, cognition, and mood that was incorporated into the WIHS core visits in April 2007 to April 2008 (WIHS visit 25)53. Extensive information on demographic and behavioral variables was obtained, including self-report of recent and past use of alcohol, marijuana, crack cocaine, powder cocaine, and heroin.

Altogether 1901 participants were assessed during that WIHS core visit, and 1552 of those women completed the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R). We excluded 157 of those participants because they reported: a) primary language other than English (n=14); b) history of stroke/cerebrovascular accidents (n=18); and/or c) use of antipsychotic medication in the past 6 months (n=130). A comparison of women who were included in this analysis (n=1395; 73% of the overall sample) versus those who were excluded (n=506) showed similar rates of cocaine and heroin use, but women who were included completed more years of education (12.4 vs. 10.6 years, p<0.001), performed better on the Wide Range Achievement Test – Revised (WRAT-R) (92.2 vs. 87.3, p<0.001), were more likely to be African-American (64% vs. 41%, p<0.001) and less likely to be Hispanic (19% vs. 48%, p<0.001), were less likely to have depressive symptoms on the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; 32% vs. 46%, p<0.001) or report using antidepressant medication (12% vs. 19%, p<0.001), and were more likely to smoke (72% vs. 66%--recent or former, p=0.01) and use marijuana (75% vs. 60%--recent+former, p<0.001).

Illicit Drug Use

The WIHS collects information on drug use at 6 months intervals consistent with the twice yearly WIHS visit schedule. Women are asked if they have used drugs since their last WIHS visit. If they have used drugs since their last WIHS visit, they are queried about the route of administration (smoking, sniffing, injecting) of each substance as well as their frequency of use. For the current study, recent illicit drug use was defined as self-reported use of crack cocaine, powder cocaine, or heroin since the last WIHS study visit (past 6 months). Former use was defined as any lifetime use of cocaine and/or heroin, but no use since the last WIHS study visit (past 6 months). Non-use was defined as no lifetime use of cocaine and/or heroin. In follow-up analyses focusing on particular drugs, crack cocaine and powder cocaine were combined into one cocaine use variable, as there was insufficient statistical power to separate the two forms of the drug. Frequency data were categorized as: once a month or less; at least once a week but less than once per day; or once a day or more.

Clinical Neuropsychological Measures

Participants completed the HVLT-R and Comalli Stroop test. The HVLT-R is a 12-item list-learning test used to measure verbal episodic memory54. Outcomes include total words recalled on Trial 1 (single trial learning) and across each of three learning trials (total learning), number of words recalled after a 25-minute delay (delayed recall), number of words correctly identified on a yes/no recognition test (recognition), percent retention (delayed recall/maximum score on Trial 2 or 3), and learning slope. Recognition scores were calculated by subtracting the number of false positives (incorrectly responding `yes' to a word not presented) from the number of hits (correctly responding `yes' to a word that was presented). The Comalli Stroop Test includes three trials55 Trials 1 and 2 measure attention and processing speed. Trial 3 measures response inhibition/executive function. On Trial 1, participants name the colors of a series of squares. On Trial 2 they read a series of color names printed in black ink. On Trial 3, participants name the color of the ink but ignore the word (e.g., when shown the word “red” printed in blue ink, say “blue” rather than “red”)55. Completion times for all three trials were recorded. The WRAT-R measured reading achievement56 and served as an index of educational quality57.

Covariates

Socio-demographic covariates and risk factors for cognitive impairment were selected based on previous literature and included study site, age, years of education, race/ethnicity, WRAT-R, CES-D (cutoff score of 16)58, recent self-reported use of antidepressant medication and Hepatitis C virus seropositivity (HCV) 48,59–66. Other covariates focused on risk behaviors and included smoking status (recent, former, never), recent hazardous alcohol use (> 7 drinks/week or more than 4 drinks in one sitting)67, and marijuana/hash use (recent, former, never). Additional clinical variables of interest were cART use (i.e., no cART therapy, cART therapy and <95% compliant, cART therapy and ≥95% compliant), recent CD4 count <200 cells/mm3, recent HIV viral load >10,000, CD4 nadir <200 cells/mm3, and duration of ART use.

Statistical Analysis

Five percent of participants were missing WRAT-R scores. Missing values were imputed using a regression based technique with race/ethnicity, age, education, site, and employment as predictors. Time-related outcomes on the Stroop were log-transformed to correct for skewness. All outcome measures were transformed to z-scores to allow for comparison of beta weights across outcome measures in models controlling for the same covariates.

Differences in demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics as a function of serostatus, illicit drug use, and their interaction were examined using ANOVAs for continuous variables and Chi-square (Χ2) tests for categorical variables. In the overall sample we conducted two series of multivariable regression analyses. The first series focused on the independent effects of serostatus and illicit drug use, adjusting for age, years of education, WRAT-R, race/ethnicity, site, depressive symptoms, self-reported use of antidepressant medication and dementia/encephalopathy (n=59), marijuana use, smoking, hazardous alcohol use, and HCV. We also adjusted for number of prior exposures to the Stroop (range 1–3). (The HVLT had not been previously administered.) The primary set of analyses focused on the interactive effect of serostatus and illicit drug use. When the interaction was significant, we further examined the effect of drug use and frequency within each serostatus group, controlling for the same set of covariates included in the first analyses. Other follow-up analyses focused on HIV-infected women and included recent CD4 count and HIV viral load, CD4 nadir, and use of antiretroviral therapy (ART). All p values are two-sided. The statistical significance level was set at p<0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS PROC GENMOD (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

Participants included 952 HIV-infected and 443 HIV-uninfected women. They ranged in age from 22 to 78 years (M=42.8, SD=9.5), with high minority representation (64% African-American, 19% Hispanic). Ten percent (n=140) reported use of cocaine and/or heroin since the previous study visit 6 months earlier; 47% (n=651) reported former use of cocaine and/or heroin, and 43% (n=604) reported never using cocaine and/or heroin in their lifetime. Among recent drug users, 70% had recently used only cocaine, 24% had recently used both cocaine and heroin, and 6% had recently used only heroin. Recent cocaine users mainly smoked crack (74%) or snorted cocaine (26%). Primary modes of recent heroin intake were snorting (17%) and injecting (14%). Critically, as shown in Supplemental Table 1, the typical pattern of recent use was at least daily (32%) or weekly (38%) smoking of crack cocaine (e.g., 73%).

Compared to HIV-uninfected women, HIV-infected women were older, had a higher minority representation, were more likely to be HCV-seropositive and to use antidepressant medication and cigarettes, and were less likely to engage in hazardous drinking, marijuana, and powder cocaine use (p's<0.05, Table 1). Compared to non-users, recent and former illicit drug users were older, less educated, were more likely to be HCV-seropositive, reported more depressive symptoms and antidepressant medication use, and were more likely to smoke, use marijuana, crack cocaine, powder cocaine, heroin, and engage in hazardous drinking (p's<0.05). Among recent users, HIV-infected women were less likely to sniff/snort cocaine and less frequently injected heroin than HIV-uninfected women (p's<0.05, Supplemental Table 1). Among HIV-infected women, recent users were less likely to be on cART and to adhere to their medication, were on ART for a shorter duration of time, and were diagnosed with HIV more recently than former and non-users (p's<0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics as a Function of Serostatus and Crack, Cocaine, and/or Heroin Use.

| Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected (n=952) | Uninfected (n=443) | |||||

|

|

||||||

| Background Characteristics (%) | Recent (n=91) | Former (n=463) | Non-users (n=398) | Recent (n=49) | Former (n=188) | Non-users (n=206) |

| Age(M, SD)D,S,DxS | 46.8 (7.7) | 46.9 (6.9) | 40.6 (9.7) | 42.8 (8.0) | 44.4 (8.9) | 34.4 (9.1) |

| WRAT-RD | 88.7 (17.4) | 90.6 (17.2) | 94.8 (18.3) | 89.7 (15.5) | 89.8 (17.9) | 95.4 (16.5) |

| Years of EducationD | 11.5 (2.8) | 11.9 (3.1) | 13.1 (2.9) | 12.2 (3.0) | 12.0 (2.7) | 13.2 (2.8) |

| Race/EthnicityS | ||||||

| African American, non-Hispanic | 70% | 64% | 64% | 61% | 58% | 63% |

| White, non-Hispanic | 10% | 16% | 16% | 12% | 11% | 8% |

| Hispanic | 14% | 18% | 15% | 21% | 28% | 24% |

| Other | 6% | 2% | 5% | 6% | 3% | 5% |

| Hepatitis C virus antibodyS,D | 56% | 45% | 6% | 29% | 28% | 4% |

| Recent | ||||||

| Depressive Symptoms, CES-D ≥16D | 54% | 35% | 28% | 50% | 34% | 19% |

| Antidepressant medication useS,D | 20% | 18% | 9% | 10% | 11% | 1% |

| Hazardous alcohol use±S, D | 21% | 5% | 3% | 35% | 9% | 6% |

| Crack cocaine use | 78% | 0% | 0% | 65% | 0% | 0% |

| Powder cocaine useS | 24% | 0% | 0% | 45% | 0% | 0% |

| Heroin use | 29% | 0% | 0% | 33% | 0% | 0% |

| Crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use prior to entry into WIHS | 92% | 98% | 0% | 92% | 94% | 0% |

| Proportion of WIHS visits where crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use was yesS,D,DxS | 53% | 7% | 0% | 52% | 19% | 0% |

| SmokingS,D | ||||||

| Never | 4% | 10% | 56% | 0% | 9% | 50% |

| Former | 85% | 50% | 19% | 84% | 60% | 32% |

| Recent | 11% | 39% | 25% | 16% | 31% | 18% |

| Marijuana UseS,D | ||||||

| Never | 7% | 9% | 53% | 2% | 7% | 40% |

| Former | 51% | 76% | 38% | 39% | 70% | 43% |

| Recent | 43% | 15% | 9% | 59% | 23% | 17% |

| Disease | ||||||

| CD4 nadir (cells/mm3)D | 208 (163) | 230 (172) | 254 (175) | |||

| CD4 Count (cells/mm3)D | ||||||

| > 500 | 29% | 44% | 51% | - | - | - |

| ≥ 200 and < 500 | 44% | 43% | 39% | |||

| <200 | 27% | 13% | 10% | |||

| Viral Load (HIV RNA, cp/ml)D | ||||||

| Undetectable | 27% | 56% | 57% | - | - | - |

| < 10,000 | 44% | 30% | 29% | |||

| ≥ 10,000 | 29% | 14% | 14% | |||

| Medication UseD | ||||||

| No cART | 50% | 33% | 32% | - | - | - |

| cART <95% compliance | 25% | 15% | 16% | - | - | - |

| cART ≥95% compliance | 25% | 52% | 52% | - | - | - |

| ART duration (years)(M, SD)‡D | 8.1 (3.4) | 9.6 (2.7) | 8.6 (3.2) | - | - | - |

Note.

Main effect of drug use significant at p<.05;

Main effect of serostatus significant at p<.05,

Drug use × Serostatus interaction significant at p<.05;

“Recent” refers to within 6 months of the most recent WIHS visit. “Former” refers to any previous use, but not in the past 6 months. cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Hazardous alcohol use reflects >7 drinks per week or more than 4 drinks in one sitting.

Reflects the mean for 859 HIV-infected women (90%) who started ART prior to data collection (WIHS visit 25).

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R)

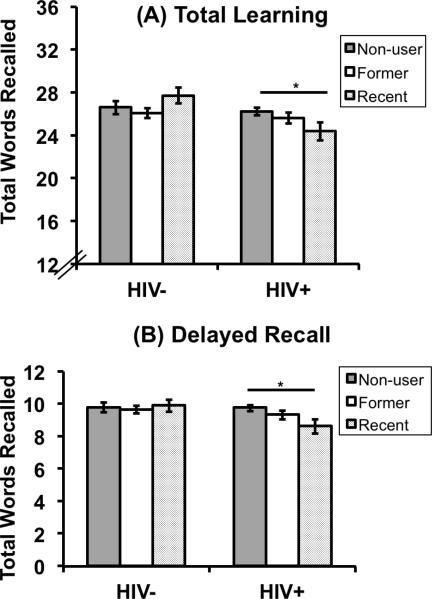

Table 2 shows the raw neuropsychological test scores as a function of serostatus and illicit drug use. HIV-infected women performed worse than HIV-uninfected women on total learning, learning slope, delayed recall, and recognition (p's<0.05; see Table 3). In adjusted analyses, recent illicit drug users performed worse than non-users on learning slope (p=0.04), delayed recall (p=0.007), and recognition (p=0.02). Recent drug users also performed worse than former drug users on recognition (p=0.03). Former drug users did not perform differently than non-users on any HVLT measure. The primary finding was that illicit drug use (recent versus nonuse) interacted with serostatus to affect Trial 1, total learning, learning slope, and delayed recall (p's<0.05; see Figure 1), but not recognition (p=0.73). Among HIV-infected women, recent illicit drug users performed worse than non-users on total learning (B=−0.36, SE=0.12, p=0.002), learning slope (B=−0.42, SE=0.12, p<0.001), and delayed recall (B=−0.45, SE=0.12, p<0.001). In contrast, among the HIV-uninfected women, recent users performed similarly to non-users on total learning (B=0.22, SE=0.15, p=0.14), learning slope (B=0.18, SE=0.15, p=0.23), and delayed recall (B=−0.05, SE=0.15, p=0.73), Whereas the interaction between serostatus and drug use for each of the four measures was driven by differences between recent users and non-users at the level of serostatus, for Trial 1 only, the interaction was driven by differences between HIV-infected and uninfected women at the level of drug use. Specifically for Trial 1, the interaction was driven by serostatus effects at the level of drug use; among recent users, HIV-infected women performed worse than HIV-uninfected women (B=−0.47, SE=0.16, p=0.004) whereas among non-users, HIV+ women perform similar to HIV-uninfected women (B=−0.02, SE=0.08, p=0.84).

Table 2.

Raw Neuropsychological Test Score Means and Statistical Comparisons by Serostatus and Crack, Cocaine, and/or Heroin Use.

| Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected (n=952) | Uninfected (n=443) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Tests | n | Recent (n=91) M (SD) | Former (n=463) M (SD) | Non-users (n=398) M (SD) | Recent (n=49) M (SD) | Former (n=188) M (SD) | Non-users (n=206) M (SD) |

| HVLT | |||||||

| Trial 1 | 1395 | 5.23 (1.84) | 5.47 (1.66) | 5.83 (1.67) | 6.12 (1.45) | 5.59 (1.69) | 5.95 (1.69) |

| Total learning | 1395 | 19.46 (5.26) | 21.17 (5.22) | 22.44 (4.82) | 23.47 (4.34) | 21.92 (4.85) | 23.26 (4.75) |

| Learning slope | 1395 | 1.31 (0.34) | 1.45 (0.35) | 1.52 (0.31) | 1.59 (0.26) | 1.50 (0.29) | 1.58 (0.30) |

| Delayed recall | 1395 | 6.26 (2.40) | 7.265 (2.60) | 8.03 (2.46) | 8.02 (2.18) | 7.76 (2.45) | 8.34 (2.34) |

| Percent retention | 1395 | 81.13 (29.71) | 83.73 (25.76) | 88.40 (21.13) | 85.36 (19.84) | 87.11 (23.40) | 88.36 (19.77) |

| Recognition | 1390 | 9.59 (2.29) | 10.08 (2.01) | 10.24 (1.99) | 10.29 (2.28) | 10.49 (1.75) | 10.75 (1.50) |

| Stroop Test | |||||||

| Trials 1&2a | 1313 | 67.79 (26.02) | 63.83 (15.57) | 60.71 (13.53) | 61.49 (14.32) | 61.91 (13.88) | 58.46 (10.65) |

| Trial 3a | 1247 | 140.34 (42.60) | 132.35 (36.21) | 126.09 (33.82) | 126.37 (26.87) | 125.50 (32.63) | 120.37 (26.55) |

Note. HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test.

Unadjusted means are displayed, but log-transformed scores were used in the statistical comparisons.

Table 3.

Results from Adjusted Analysis Examining the Effect of Serostatus, Crack, Cocaine, and/or Heroin use, and their Interaction on Cognitive Function.

| Multivariable Linear Regression Models | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: No interactions in model | Model 2: Interactions included in model | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Serostatus | Drug use | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| HIV+ vs. HIV− | Recent vs. Non-users | Former vs. Non-users | Recent vs. Former | Adjusted R2 | Recent vs. non-users × Status | Former vs. non-users × Status | Adjusted R2 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Tests | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | ||

| HVLT | ||||||||

| Trial 1 | −.07 (.06) | −.04 (.10) | −.09 (.07) | .05 (.09) | .16 | −.43 (.18)* | −.01 (.11) | .17 |

| Total learning | −.14 (.05)** | −.16 (.09) | −.11 (.06) | −.05 (.09) | .25 | −.58 (.17)** | .01 (.11) | .26 |

| Learning slope | −.16 (.05)** | −.20 (.10)* | −.10 (.07) | −.10 (.09) | .19 | −.60 (.18)*** | −.01 (.11) | .20 |

| Delayed recall | −.11 (.05)* | −.27 (.10)** | −.12 (.07) | −.15 (.09) | .22 | −.50 (.17)** | −.11 (.11) | .23 |

| Percent retention | −.02 (.06) | −.15 (.11) | −.05 (.07) | −.09 (.10) | .03 | - | - | - |

| Recognition | −.16 (.06)** | −.24 (.11)* | −.04 (.07) | −.20 (.09)* | .15 | - | - | - |

| Stroop Test | ||||||||

| Trials 1&2a | −.05 (.05) | −.04 (.10) | .02 (.07) | −.07 (.09) | .25 | - | - | - |

| Trial 3a | −.05 (.06) | .04 (.11) | .06 (.07) | −.02 (.10) | .21 | - | - | - |

Note.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

For Stroop, we also controlled for the number of times a woman was exposed to the test (range 1–3 times).

B = Parameter estimates for each factor modeled individually. SE = standard error. HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test.

All models are adjusted for age, education, race/ethnicity, WRAT-R, site, depressive symptoms, self-reported use of antidepressant medication, marijuana use, smoking, hazardous alcohol use, self-reported dementia, and Hepatitis C virus antibody.

Figure 1.

Results from adjusted analysis examining the effect of serostatus, crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use, and their interaction on the HVLT total learning and delayed free recall.

Note. *p<0.01.There was a significant interaction between crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use (specifically current versus non-users) and serostatus on total learning (p<0.01) and delayed recall (p<0.01). Among HIV-infected women, recent illicit drug users performed worse than non-users on total learning (p=0.002) and delayed recall (p<0.001). All models are adjusted for age, education, race/ethnicity, WRAT-R, site, depressive symptoms, self-reported use of antidepressant medication, marijuana use, smoking, hazardous alcohol use, self-reported dementia, and Hepatitis C virus antibody.

Follow-up analyses probed the interaction between serostatus and recent drug use further to assess which particular drug (i.e., cocaine with or without heroin; heroin with or without cocaine) contributed to the interaction. Serostatus interacted with cocaine use (recent versus non-use; p's<.05) and heroin use (recent versus non-use; p's<.01) to impact total learning and learning slope. Serostatus interacted with cocaine use (non-use versus recent) but not heroin use to impact delayed recall (p=0.04). Additional analyses focused on dose response by examining the frequency of smoking crack on total learning, learning slope and delayed recall (see Supplemental Table 2). Serostatus interacted with frequency of crack use (≥ 1 week versus non-use) to affect total learning (p= 0.03) and delayed recall (p=0.005). Again the patterns were that drug use impacted performance among HIV-infected women only.

In analyses of HIV-infected women only, the effects of illicit drug use (recent versus non-use) on total learning, learning slope, and delayed recall remained significant after controlling for disease characteristics (i.e., CD4 count, viral load, medication use, duration on ART) (see Table 4). Recent users also performed worse than former users on learning slope and delayed recall, and former users performed worse than non-users on delayed recall. Comparing recent users to non-users on total learning and learning slope, recent heroin use predicted poorer performance (B=−0.42, SE=0.19, p=0.03 and B=−0.58, SE=0.24, p=0.01, respectively). Cocaine use predicted poorer performance on delayed recall (B=−0.32, SE=0.15, p=0.03). There was also a trend for heroin use to predict poorer performance on delayed recall (B=−0.34, SE=0.20, p=0.08). In HIV-infected women, the effects of smoking crack/cocaine at least once a week versus non-use remained significant on both total learning (B=−0.39, SE=0.19, p=0.04) and delayed recall (B=− 0.40, SE=0.19, p=0.04) after controlling for disease characteristics (i.e., CD4 count, viral load, medication use, duration on ART).

Table 4.

Results from Adjusted Analysis Examining the Effect of Crack, Cocaine, and/or Heroin use in HIV-infected Women on Cognitive Function.

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Trial 1 | Total learning | Learning Slope | Delayed Recall | |

|

|

||||

| Models | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) |

| Adjusted for only non-HIV specific factors a | ||||

| Recent vs. non-users | −.16 (.13) | −.32 (.12)* | −.45 (.15)** | −.43 (.12)*** |

| Former vs. non-users | −.10 (.08) | −.13 (.08) | −.14 (.10) | −.19 (.08)* |

| Recent vs. Former | −.05 (.11) | −.19 (.11) | −.31 (.13)* | −.24 (.11)* |

| Adjusted R2 | .17 | .27 | .20 | .25 |

|

| ||||

| Adjusted for non-HIV specific factors and CD4, viral load, medication use, and duration on ART b | ||||

| Recent vs. non-users | −.14 (.16) | −.29 (.12)* | −.42 (.15)** | −.44 (.13)*** |

| Former vs. non-users | −.10 (.08) | −.12 (.08) | −.12 (.10) | −.17 (.08)* |

| Recent vs. Former | −.04 (.11) | −.17 (.11) | −.30 (.13)* | −.27 (.11)* |

| Adjusted R2 | .17 | .27 | .21 | .25 |

Note.

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

B = Parameter estimates for each factor modeled individually. SE = standard error.

Adjusted for age, education, race/ethnicity, WRAT-R, site, depressive symptoms, self-reported use of antidepressant medication, marijuana use, smoking, hazardous alcohol use, self-reported dementia, and Hepatitis C virus antibody

Adjusted for site, depressive symptoms, self-reported use of antidepressant medication, marijuana use, smoking, hazardous alcohol use, self-reported dementia, Hepatitis C virus antibody, recent cd4 count and viral load, cd4 nadir, medication use, and duration on ART.

Stroop Test

Neither HIV-infection nor drug use significantly impacted performance on the Stroop test (Trials 1&2 or Trial 3, p's>0.05). In addition, there were no significant interactions between illicit drug use and serostatus on the Stroop Test (p's>0.05).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate the separate and interactive effects of illicit drug use and HIV infection on verbal learning and memory, processing speed, and executive function. To our knowledge this is the first study to examine this issue, and we provide new evidence that in women recent illicit drug use may interact with HIV serostatus to negatively impact verbal learning and memory but not processing speed or response inhibition. The typical pattern of recent drug use was at least daily or weekly smoking of crack cocaine. The pattern of effects across different measures suggests that recent drug use (compared to non-use) affects learning and memory more among HIV-infected than HIV-uninfected women. Cocaine use interacted with HIV serostatus to affect learning and delayed recall, but not recognition. Heroin interacted with HIV serostatus to affect only learning. Serostatus also interacted with frequency of crack cocaine use to negatively affect learning and delayed recall (but not recognition) more in HIV-infected women. HIV infection, regardless of substance use history, was associated with deficits in learning (i.e., impaired total learning, learning slope) and delayed memory (impaired delayed recall, recognition), with no impairment in retention or attention (trial 1). Deficits in verbal learning and memory encoding might have important implications for clinical management of HIV, as neurocognitive deficits have been shown to relate to poor medication treatment adherence among HIV-infected individuals68. Our results underscore the importance of effective substance abuse treatment in HIV-infected individuals.

Few studies have sufficient statistical power to test for an interactive effect of HIV and drugs of abuse on cognition69. The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) has investigated additive and potential interactive effects of methamphetamine and HIV. They found additive effects of methamphetamine use and HIV infection on neuropsychological function70, neural and glial injury71, and cerebral blood flow (CBF)72. The only previous study to investigate the interactive effects of HIV and cocaine use on verbal memory (n= 237 gay and bisexual seropositive and seronegative African-American men) found no significant main effects for serostatus or cocaine use and no interaction of HIV and cocaine use on verbal memory, differences that were attributed to confounding effects of alcohol73.

Several studies have provided important insights into how HIV serostatus influences cognition among individuals using illicit substances48,74–77. Compared to HIV-uninfected drug users, HIV-infected drug users perform worse on tests of procedural learning74, prospective memory75, decision-making78, and working memory76,77, deficits consistent with the affinity of HIV for the striatum and prefrontal cortex. However, study samples were typically male, of small size (n < 100) and did not include a non-drug using comparison group48,74–77. A study of 43 women with a history of illicit drug use did not identify a relationship with cocaine or heroin use within the past 12 months and noted no interaction between HIV status and recent drug use on verbal memory or any cognitive domain; however, cell sizes were small (e.g. n=9)79. We similarly did not find a difference between recent and former users on total learning or delayed recall.

In our full sample of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women there were no differences between former drug users and non-users on any neurocognitive outcome, suggesting recovery of cognitive function. In contrast, in our HIV-infected sample, former users performed worse than non-users on delayed recall. This pattern provides further evidence that drug use has a stronger negative impact on cognitive function in HIV-infected women. Recent use may have a larger negative impact than past use due to the synergistic neurotoxicity of HIV viral proteins with cocaine and heroin, with potential for recovery of cognitive function with sustained abstinence80–82.

Other studies have looked within HIV-infected cohorts for effects of drug use on cognition, but without an HIV-uninfected control group. Our findings are consistent with other findings showing an effect of active cocaine dependence on delayed recall and visuospatial construction in HIV-infected individuals (n=64, 72% male), with recall having the largest effect size (d=.93)83. As in the present study, CHARTER (75% male) found no impact of lifetime history of substance use on tests of processing speed and executive function84. CHARTER also found that lifetime heroin dosage related to delayed memory. In comparison, we found that delayed memory related to recent use of cocaine, particularly use of crack cocaine more than once per week. Recent heroin use was associated with worse total learning in HIV-infected women. Recent stimulant use was associated with impairments in sustained attention in a sample of 40 HIV-infected individuals; but verbal memory was not examined and cocaine and methamphetamine use were combined85.

Contrary to our hypothesis, serostatus and illicit drug use did not interact to affect inhibitory control. The scientific literature is mixed with respect to whether drug use impacts Stroop performance. A study of 159 men with at least one substance use disorder found a negative effect of HIV infection on performance during the incongruent condition of a computerized Reaction Time Stroop48. Other studies have failed to find a negative effect of cocaine use on Stroop performance in HIV-uninfected individuals10,15,86 but have found effects on other executive measures such as the go/no test15,16,87.

The use of the HVLT precludes a clear understanding of whether the interactive effects of HIV and recent drug use represent a deficit in acquisition/encoding, retention, and/or retrieval. However, the pattern of interactions provides tentative support of potential effects on acquisition and retrieval, with spared retention. Specifically, HIV serostatus interacted with recent drug use to affect acquisition (total learning and learning slope) and retrieval (impaired delayed recall but spared recognition), with no effect on retention. Interestingly, that same pattern of effects was evident in follow-up analyses examining the impact of cocaine use specifically as well as frequency of crack cocaine use. Crack cocaine was the primary drug of choice among recent users. Moreover, analyses of recent drug use in HIV-infected women alone showed deficits in acquisition (total learning and learning slope) and retrieval (impaired delayed recall but spared recognition), with no effect on retention. This pattern of interactive effects differs from the pattern of main effects associated with HIV serostatus and recent drug use, which were characterized by deficits in acquisition only. The apparent pattern of interactive effects on acquisition and retrieval suggests that HIV and cocaine might interact to influence subcortical-prefrontal circuitry. Chronic cocaine use has been associated with anatomical changes, cerebrovascular defects, and functional alterations in the prefrontal cortex88–92. Given the known executive component, such as encoding strategies, on episodic memory performance, deficits in subcortical-prefrontal circuitry may contribute to deficits in verbal memory93–95. A neuroimaging study of delayed verbal memory in HIV-infected women demonstrated alterations in hippocampal function with decreased activation during verbal encoding and increased during verbal retrieval96. Importantly, the magnitude of those alterations correlated with worse delayed recall on the HVLT96. Together these findings suggest that cocaine and heroin use in HIV-infected women may also lead to further alterations in hippocampal function during verbal encoding.

Our study had several limitations. First, self-report data was used to determine drug use categories. If women who had recently used illicit drugs reported never using cocaine, the impact of illicit drug use on cognition may be underestimated. Second, toxicology screens were not administered in conjunction with neurocognitive testing, so it is possible that the recent users could have been under the influence of drugs or experiencing drug withdrawal. WIHS staff are trained in detecting illicit substance use and reschedule women for cognitive testing if they appear to be under the influence of illicit substances. Third, given the use of multiple illicit substances in our cohort, we could not fully disentangle the effects of different substances on cognition. We found that cocaine use (with or without heroin) predicted worse total learning, learning slope, and delayed recall, and heroin use (with or without cocaine) predicted worse total learning and learning slope among HIV-infected women. Fourth, only two neurocognitive tests were administered, so we could not evaluate effects across a broader spectrum of cognitive domains. Fifth, although effect sizes are 0.11 or lower, the effect sizes for the interaction between serostatus and drug use are equal to or exceed the effect sizes associated with HIV serostatus alone or drug use alone. Lastly, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes the possibility of examining causality. We presume that illicit drug use leads to poor memory performance but it is possible that learning and memory deficits preceded drug use for at least some women. The last two limitations are being now addressed with the collection of longitudinal cognitive data in the WIHS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Study Funding: Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC, Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co- funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131). V. Grauzas' effort on this project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1F31DA028573). L. Rubin's effort was supported by grant number K12HD055892 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sacktor N, McDermott MP, Marder K, et al. HIV-associated cognitive impairment before and after the advent of combination therapy. J Neurovirol. 2002 Apr;8(2):136–142. doi: 10.1080/13550280290049615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heaton RK, Grant I, Butters N, et al. The HNRC 500--neuropsychology of HIV infection at different disease stages. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995 May;1(3):231–251. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benedict RH, Mezhir JJ, Walsh K, Hewitt RG. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type-1-associated cognitive dysfunction on activities of daily living and quality of life. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2000 Aug;15(6):535–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heaton RK, Velin RA, McCutchan JA, et al. Neuropsychological impairment in human immunodeficiency virus-infection: implications for employment. HNRC Group. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Psychosom Med. 1994 Jan-Feb;56(1):8–17. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Gorp WG, Rabkin JG, Ferrando SJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric predictors of return to work in HIV/AIDS. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007 Jan;13(1):80–89. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cattie JE, Woods SP, Arce M, Weber E, Delis DC, Grant I. Construct validity of the item-specific deficit approach to the California verbal learning test (2nd Ed) in HIV infection. Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26(2):288–304. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2011.653404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott JC, Woods SP, Patterson KA, et al. Recency effects in HIV-associated dementia are characterized by deficient encoding. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(8):1336–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woods SP, Scott JC, Dawson MS, et al. Construct validity of Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised component process measures in an HIV-1 sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2005 Dec;20(8):1061–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beatty WW, Katzung VM, Moreland VJ, Nixon SJ. Neuropsychological performance of recently abstinent alcoholics and cocaine abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995 Mar;37(3):247–253. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)01072-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry J, van Gorp WG, Herzberg DS, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in abstinent cocaine abusers: preliminary findings after two weeks of abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993 May;32(3):231–237. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolla KI, Funderburk FR, Cadet JL. Differential effects of cocaine and cocaine alcohol on neurocognitive performance. Neurology. 2000 Jun 27;54(12):2285–2292. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.12.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Malley S, Adamse M, Heaton RK, Gawin FH. Neuropsychological impairment in chronic cocaine abusers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1992;18(2):131–144. doi: 10.3109/00952999208992826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strickland TL, Mena I, Villanueva-Meyer J, et al. Cerebral perfusion and neuropsychological consequences of chronic cocaine use. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993 Fall;5(4):419–427. doi: 10.1176/jnp.5.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darke S, Sims J, McDonald S, Wickes W. Cognitive impairment among methadone maintenance patients. Addiction. 2000 May;95(5):687–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9556874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolla KI, Rothman R, Cadet JL. Dose-related neurobehavioral effects of chronic cocaine use. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999 Summer;11(3):361–369. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hester R, Garavan H. Executive dysfunction in cocaine addiction: evidence for discordant frontal, cingulate, and cerebellar activity. J Neurosci. 2004 Dec 8;24(49):11017–11022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3321-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant S, Contoreggi C, London ED. Drug abusers show impaired performance in a laboratory test of decision making. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38(8):1180–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mintzer MZ, Stitzer ML. Cognitive impairment in methadone maintenance patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002 Jun 1;67(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aksenov MY, Aksenova MV, Nath A, Ray PD, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Cocaine-mediated enhancement of Tat toxicity in rat hippocampal cell cultures: the role of oxidative stress and D1 dopamine receptor. Neurotoxicology. 2006 Mar;27(2):217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aksenov MY, Hasselrot U, Wu G, et al. Temporal relationships between HIV-1 Tat-induced neuronal degeneration, OX-42 immunoreactivity, reactive astrocytosis, and protein oxidation in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 2003 Oct 10;987(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagasra O, Pomerantz RJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in the presence of cocaine. J Infect Dis. 1993 Nov;168(5):1157–1164. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhillon NK, Williams R, Peng F, et al. Cocaine-mediated enhancement of virus replication in macrophages: implications for human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. J Neurovirol. 2007 Dec;13(6):483–495. doi: 10.1080/13550280701528684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiala M, Eshleman AJ, Cashman J, et al. Cocaine increases human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neuroinvasion through remodeling brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neurovirol. 2005 Jul;11(3):281–291. doi: 10.1080/13550280590952835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiala M, Gan XH, Zhang L, et al. Cocaine enhances monocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier. Cocaine's connection to AIDS dementia and vasculitis? Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;437:199–205. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5347-2_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gekker G, Hu S, Wentland MP, Bidlack JM, Lokensgard JR, Peterson PK. Kappa-opioid receptor ligands inhibit cocaine-induced HIV-1 expression in microglial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004 May;309(2):600–606. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrod SB, Mactutus CF, Fitting S, Hasselrot U, Booze RM. Intra-accumbal Tat1-72 alters acute and sensitized responses to cocaine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008 Oct;90(4):723–729. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kendall SL, Anderson CF, Nath A, et al. Gonadal steroids differentially modulate neurotoxicity of HIV and cocaine: testosterone and ICI 182,780 sensitive mechanism. BMC Neurosci. 2005;6:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson PK, Gekker G, Chao CC, Schut R, Molitor TW, Balfour HH., Jr. Cocaine potentiates HIV-1 replication in human peripheral blood mononuclear cell cocultures. Involvement of transforming growth factor-beta. J Immunol. 1991 Jan 1;146(1):81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds JL, Mahajan SD, Bindukumar B, Sykes D, Schwartz SA, Nair MP. Proteomic analysis of the effects of cocaine on the enhancement of HIV-1 replication in normal human astrocytes (NHA) Brain Res. 2006 Dec 6;1123(1):226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth MD, Tashkin DP, Choi R, Jamieson BD, Zack JA, Baldwin GC. Cocaine enhances human immunodeficiency virus replication in a model of severe combined immunodeficient mice implanted with human peripheral blood leukocytes. J Infect Dis. 2002 Mar 1;185(5):701–705. doi: 10.1086/339012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turchan J, Anderson C, Hauser KF, et al. Estrogen protects against the synergistic toxicity by HIV proteins, methamphetamine and cocaine. BMC Neurosci. 2001;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brack-Werner R. Astrocytes: HIV cellular reservoirs and important participants in neuropathogenesis. AIDS. 1999 Jan 14;13(1):1–22. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurwell JA, Nath A, Sun Q, et al. Synergistic neurotoxicity of opioids and human immunodeficiency virus-1 Tat protein in striatal neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 2001;102(3):555–563. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00461-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khurdayan VK, Buch S, El-Hage N, et al. Preferential vulnerability of astroglia and glial precursors to combined opioid and HIV-1 Tat exposure in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2004 Jun;19(12):3171–3182. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu S, Sheng WS, Lokensgard JR, Peterson PK. Morphine potentiates HIV-1 gp120-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Infect Dis. 2005 Mar 15;191(6):886–889. doi: 10.1086/427830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkatesan A, Nath A, Ming GL, Song H. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis: regulation by HIV and drugs of abuse. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007 Aug;64(16):2120–2132. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7063-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maki PM, Martin-Thormeyer E. HIV, cognition and women. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009 Jun;19(2):204–214. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9093-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Reynolds EK, Daughters SB, Curtin JJ. Risk factors in the relationship between gender and crack/cocaine. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007 Apr;15(2):165–175. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Brien MS, Anthony JC. Risk of becoming cocaine dependent: epidemiological estimates for the United States, 2000–2001. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005 May;30(5):1006–1018. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen K, Kandel D. Relationship between extent of cocaine use and dependence among adolescents and adults in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002 Sep 1;68(1):65–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edlin BR, Irwin KL, Faruque S, et al. Intersecting epidemics--crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. Multicenter Crack Cocaine and HIV Infection Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1994 Nov 24;331(21):1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page B, Campa A. Crack-cocaine use accelerates HIV disease progression in a cohort of HIV-positive drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Jan 1;50(1):93–99. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181900129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webber MP, Schoenbaum EE, Gourevitch MN, Buono D, Klein RS. A prospective study of HIV disease progression in female and male drug users. AIDS. 1999 Feb 4;13(2):257–262. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Cohen MH, et al. Crack cocaine, disease progression, and mortality in a multicenter cohort of HIV-1 positive women. AIDS. 2008 Jul 11;22(11):1355–1363. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830507f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thorpe LE, Frederick M, Pitt J, et al. Effect of hard-drug use on CD4 cell percentage, HIV RNA level, and progression to AIDS-defining class C events among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004 Nov 1;37(3):1423–1430. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000127354.78706.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, et al. Initial validation of a screening battery for the detection of HIV-associated cognitive impairment. Clin Neuropsychol. 2004 May;18(2):234–248. doi: 10.1080/13854040490501448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Hardy DJ, Granholm E, Siegle G. Computerized and traditional stroop task dysfunction in HIV-1 infection. Neuropsychology. 1999 Apr;13(2):306–316. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.13.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin EM, Novak RM, Fendrich M, et al. Stroop performance in drug users classified by HIV and hepatitis C virus serostatus. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004 Mar;10(2):298–300. doi: 10.1017/S135561770410218X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore DJ, Masliah E, Rippeth JD, et al. Cortical and subcortical neurodegeneration is associated with HIV neurocognitive impairment. AIDS. 2006 Apr 4;20(6):879–887. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218552.69834.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Frol AB, et al. Interrater reliability of clinical ratings and neurocognitive diagnoses in HIV. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004 Sep;26(6):759–778. doi: 10.1080/13803390490509565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005 Sep;12(9):1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998 Mar;9(2):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maki PM, Rubin LH, Cohen M, Golub ET, Greenblatt RM, Young M, Schwartz RM, Anastos K, Cook JA. Depressive symptoms are increased in the early perimenopausal stage in ethnically diverse human immunodeficiency virus-infected and human immunodeficiency virus-uninfected women. Menopause. 2012 Nov;19(11):1215–23. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318255434d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised: Normative Data and Analysis of Inter-Form and Test-Retest Relability. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1998;12(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Comalli PE, Jr., Wapner S, Werner H. Interference effects of Stroop color-word test in childhood, adulthood, and aging. J Genet Psychol. 1962 Mar;100:47–53. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1962.10533572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jastak S, Wilkinson GS, Jastak J. Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised. Jastak Associates Inc; Indianapolis: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, Small SA, Stern Y. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002 Mar;8(3):341–348. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cherner M, Letendre S, Heaton RK, et al. Hepatitis C augments cognitive deficits associated with HIV infection and methamphetamine. Neurology. 2005 Apr 26;64(8):1343–1347. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158328.26897.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Durvasula RS, Miller EN, Myers HF, Wyatt GE. Predictors of neuropsychological performance in HIV positive women. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2001 Apr;23(2):149–163. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.2.149.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goggin KJ, Zisook S, Heaton RK, et al. Neuropsychological performance of HIV-1 infected men with major depression. HNRC Group. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1997 Sep;3(5):457–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Letendre SL, Cherner M, Ellis RJ, et al. The effects of hepatitis C, HIV, and methamphetamine dependence on neuropsychological performance: biological correlates of disease. AIDS. 2005 Oct;19(Suppl 3):S72–78. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000192073.18691.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manly JJ, Smith C, Crystal HA, et al. Relationship of ethnicity, age, education, and reading level to speed and executive function among HIV+ and HIV- women: The Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Neurocognitive Substudy. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011 Oct;33(8):853–863. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.547662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richardson JL, Nowicki M, Danley K, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in a cohort of HIV- and hepatitis C virus-infected women. AIDS. 2005 Oct 14;19(15):1659–1667. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000186824.53359.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ryan EL, Morgello S, Isaacs K, Naseer M, Gerits P. Neuropsychiatric impact of hepatitis C on advanced HIV. Neurology. 2004 Mar 23;62(6):957–962. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115177.74976.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valcour Victor, Maki Pauline, Bacchetti Peter, Anastos Kathryn, Crystal Howard, Young Mary, Mack Wendy J., Cohen Mardge, Golub Elizabeth T., Tien Phyllis C. Insulin resistance and cognition among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adult women: The Women's Interagency HIV Study. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2012 May;28(5):447–453. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Willenbring ML, Massey SH, Gardner MB. Helping patients who drink too much: an evidence-based guide for primary care clinicians. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Jul 1;80(1):44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, et al. Medication adherence among HIV+ adults: effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology. 2002 Dec 24;59(12):1944–1950. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038347.48137.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martin-Thormeyer EM, Paul RH. Drug abuse and hepatitis C infection as comorbid features of HIV associated neurocognitive disorder: neurocognitive and neuroimaging features. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009 Jun;19(2):215–231. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Carey CL, et al. Methamphetamine dependence increases risk of neuropsychological impairment in HIV infected persons. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004 Jan;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704101021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang L, Ernst T, Speck O, Grob CS. Additive effects of HIV and chronic methamphetamine use on brain metabolite abnormalities. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Feb;162(2):361–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ances BM, Vaida F, Cherner M, et al. HIV and chronic methamphetamine dependence affect cerebral blood flow. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011 Sep;6(3):409–419. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9270-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Durvasula RS, Myers HF, Satz P, et al. HIV-1, cocaine, and neuropsychological performance in African American men. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000 Mar;6(3):322–335. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700633076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gonzalez R, Jacobus J, Amatya AK, Quartana PJ, Vassileva J, Martin EM. Deficits in complex motor functions, despite no evidence of procedural learning deficits, among HIV+ individuals with history of substance dependence. Neuropsychology. 2008 Nov;22(6):776–786. doi: 10.1037/a0013404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martin EM, Nixon H, Pitrak DL, et al. Characteristics of prospective memory deficits in HIV-seropositive substance-dependent individuals: preliminary observations. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2007 Jul;29(5):496–504. doi: 10.1080/13803390600800970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martin EM, Pitrak DL, Rains N, et al. Delayed nonmatch-to-sample performance in HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative polydrug abusers. Neuropsychology. 2003 Apr;17(2):283–288. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.17.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martin EM, Sullivan TS, Reed RA, et al. Auditory working memory in HIV-1 infection. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2001 Jan;7(1):20–26. doi: 10.1017/s1355617701711022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martin EM, Pitrak DL, Weddington W, et al. Cognitive impulsivity and HIV serostatus in substance dependent males. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004 Nov;10(7):931–938. doi: 10.1017/s1355617704107054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mason KI, Campbell A, Hawkins P, Madhere S, Johnson K, Takushi-Chinen R. Neuropsychological functioning in HIV-positive African-American women with a history of drug use. J Natl Med Assoc. 1998 Nov;90(11):665–674. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hanlon CA, Dufault DL, Wesley MJ, Porrino LJ. Elevated gray and white matter densities in cocaine abstainers compared to current users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011 Dec;218(4):681–692. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Di Sclafani V, Tolou-Shams M, Price LJ, Fein G. Neuropsychological performance of individuals dependent on crack-cocaine, or crack-cocaine and alcohol, at 6 weeks and 6 months of abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002 Apr 1;66(2):161–171. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00197-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gould RW, Gage HD, Nader MA. Effects of chronic cocaine self-administration on cognition and cerebral glucose utilization in Rhesus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry. 2012 Nov 15;72(10):856–863. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meade CS, Conn NA, Skalski LM, Safren SA. Neurocognitive impairment and medication adherence in HIV patients with and without cocaine dependence. J Behav Med. 2011 Apr;34(2):128–138. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9293-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Byrd DA, Fellows RP, Morgello S, et al. Neurocognitive impact of substance use in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Oct 1;58(2):154–162. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318229ba41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Levine AJ, Hardy DJ, Miller E, Castellon SA, Longshore D, Hinkin CH. The effect of recent stimulant use on sustained attention in HIV-infected adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2006 Jan;28(1):29–42. doi: 10.1080/13803390490918066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Woicik PA, Moeller SJ, Alia-Klein N, et al. The neuropsychology of cocaine addiction: recent cocaine use masks impairment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009 Apr;34(5):1112–1122. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Verdejo-Garcia AJ, Lopez-Torrecillas F, Aguilar de Arcos F, Perez-Garcia M. Differential effects of MDMA, cocaine, and cannabis use severity on distinctive components of the executive functions in polysubstance users: a multiple regression analysis. Addict Behav. 2005 Jan;30(1):89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bolla K, Ernst M, Kiehl K, et al. Prefrontal cortical dysfunction in abstinent cocaine abusers. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004 Fall;16(4):456–464. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16.4.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Franklin TR, Acton PD, Maldjian JA, et al. Decreased gray matter concentration in the insular, orbitofrontal, cingulate, and temporal cortices of cocaine patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2002 Jan 15;51(2):134–142. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, et al. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. Synapse. 1993 Jun;14(2):169–177. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Volkow ND, Hitzemann R, Wang GJ, et al. Long-term frontal brain metabolic changes in cocaine abusers. Synapse. 1992 Jul;11(3):184–190. doi: 10.1002/syn.890110303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Volkow ND, Mullani N, Gould KL, Adler S, Krajewski K. Cerebral blood flow in chronic cocaine users: a study with positron emission tomography. Br J Psychiatry. 1988 May;152:641–648. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Delis DC, Peavy G, Heaton R, et al. Do patients with HIV-associated minor cognitive/motor disorder exhibit a “subcortical” memory profile? evidence using the California Verbal Learning Test. Assessment. 1995;2(2):151–165. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gongvatana A, Woods SP, Taylor MJ, Vigil O, Grant I. Semantic clustering inefficiency in HIV-associated dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007 Winter;19(1):36–42. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Peavy G, Jacobs D, Salmon DP, et al. Verbal memory performance of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence of subcortical dysfunction. The HNRC Group. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1994 Aug;16(4):508–523. doi: 10.1080/01688639408402662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maki PM, Cohen MH, Weber K, et al. Impairments in memory and hippocampal function in HIV-positive vs HIV-negative women: a preliminary study. Neurology. 2009 May 12;72(19):1661–1668. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a55f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.