Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the association between sleep disorders and lower urinary tract symptoms in patients who had visited urology departments.

Methods

This was an independent cross-sectional, observational study. Outpatients who had visited the urology departments at the Kinki University School of Medicine or the Sakai Hospital, Kinki University School of Medicine, between August 2011 and January 2012 were assessed using the Athens Insomnia Scale and the International Prostate Symptom Score.

Results

In total, 1174 patients (mean age, 65.7 ± 13.7 years), with 895 men (67.1 ± 13.2 years old) and 279 women (61.4 ± 14.6 years old), were included in the study. Approximately half of these patients were suspected of having a sleep disorder. With regard to the International Prostate Symptom Score subscores, a significant increase in the risk for suspected sleep disorders was observed among patients with a post-micturition symptom (the feeling of incomplete emptying) subscore of ≥1 (a 2.3-fold increase), a storage symptom (daytime frequency + urgency + nocturia) subscore of ≥5 (a 2.7-fold increase), a voiding symptom (intermittency + slow stream + hesitancy) subscore of ≥2 (a 2.6-fold increase), and a nocturia subscore of ≥2 (a 1.9-fold increase).

Conclusion

The results demonstrated that the risk factors for sleep disorders could also include voiding, post-micturition, and storage symptoms, in addition to nocturia.

Keywords: lower urinary tract symptoms, sleep disturbance, urological disease

Introduction

It has been indicated that in the present Japanese society, which is shifting to a “24-hour society” with a rapidly progressing aging population, one in five people complain of a sleep disorder.1 Sleep disorders interfere with people’s social activities and quality of life (QOL); further, they act as risk factors for the development of lifestyle-related diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.2 In addition, sleep disorders have been closely associated with nocturia,3–9 where the percentage of individuals who void three or more times at night increases among those aged ≥ 60 years; this is observed in approximately 30% of men and 20% of women who are aged ≥ 70 years.10 Moreover, some studies have reported that balance disorders (staggering) among individuals who rise to urinate at night could lead to increased mortality due to the associated risk of falling.11,12

Therefore, sleep disorders represent a major concern in the present 24-hour Japanese society that is witnessing an aging population. Consequently, it is likely that even nonspecialists in sleep disorders will be increasingly required to examine patients suffering from insomnia. In addition, given that lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and sleep disorders deteriorate as people age, the authors reasoned that studying the association between LUTS and sleep disorders would provide important information in considering treatment options, thereby contributing to the improvement of patients’ QOL. However, with the exception of nocturia, few reports have been published on the association between LUTS and sleep disorders among patients who receive outpatient urological treatment. Therefore, in this study, we have investigated the association between LUTS and sleep disorders, and in patients who visited urology departments for treatment. Further, this study aims to facilitate the early detection of insomnia.

Methods

This was an independent cross-sectional, observational study. A questionnaire was administered among 1174 outpatients who visited the Department of Urology, Kinki University School of Medicine, or the Department of Urology, Sakai Hospital, Kinki University School of Medicine between August 2011 and January 2012, and who were capable of understanding the interview sheets on their own. The 1174 subjects (mean age: 65.7 ± 14.6 years) consisted of 895 males (67.1 ± 13.2 years) and 279 females (61.4 ± 14.6 years). A total of 746 patients were 65 years of age and over, and 428 were less than 65 years.

The questionnaire was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kinki University, and consent was obtained from patients before the onset of the study.

Sleep disorders

The questionnaire-based evaluation of sleep disorders considered whether or not the patient had used a sleep inducer, and also considered the patient’s score on the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) (scores < 4 indicated no suspicion of sleep disorders; scores = 4–5 indicated some suspicion of sleep disorders; and scores ≥ 6 indicated suspicion of sleep disorders),13,14 which was established by the World Health Organization Worldwide Project on Sleep and Health. The first screening was conducted on the AIS, and then the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, second edition15 was used to assess: (1) subjective insomnia; (2) the presence of insomnia in an environment suited for sleep; and (3) functional impairments during the daytime (eg, daytime sleepiness, as well as impaired attentive abilities and concentration).

LUTS

LUTS were evaluated using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS).

The IPSS is an eight-question (seven questions on symptoms, and one question on QOL) written screening tool used to screen for, rapidly diagnose, track the symptoms of, and propose the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Presently, it is being used to evaluate LUTS associated with BPH as well as a variety of other diseases. The seven questions on symptoms are related to the urinary system and include feelings of incomplete emptying of the bladder, daytime frequency of urination, intermittency of urination, urgency to urinate, weak urinary stream, difficulty urinating, and nocturia. These questions referred to the period during the last month, and each question was assigned a score from 1 to 5 for a maximum of 35 points. The eighth question on the QOL was assigned a score from 1 to 6.

QOL

QOL was evaluated according to the patients’ current satisfaction level (0, very satisfied; 1, satisfied; 2, mostly satisfied; 3, uncertain; 4, somewhat dissatisfied; 5, dissatisfied; and 6, very dissatisfied) in order to assess the association of sleep disorders and LUTS.

Other urological diseases

The definition of these diseases, including that for overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms, mainly remained the same prior to and during treatment, as well as during follow-up. OAB patients were defined as those with a pretreatment OAB symptom score of ≥2 on the urgency subscale, and with an overall score of ≥3. BPH patients were defined as those with an IPSS ≥ 8, a prostate size ≥ 20 g, and a maximum flow rate of ≤10 mL/second. Prostate cancer patients were defined as those with a histological diagnosis of prostate cancer using needle biopsy. Bladder cancer patients were defined as those who had a tumor confirmed prior to treatment using cystoscopy, and those who had been confirmed histologically during treatment and at follow-up.

Significant factors selected by univariate analysis were assessed by multivariate analysis using the multiple logistic regression model in order to analyze suspected sleep disorders as well as related factors. Suspected sleep disorders were characterized by the use of a sleep inducer, an AIS score of ≥6, and AIS scores of 4–5. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

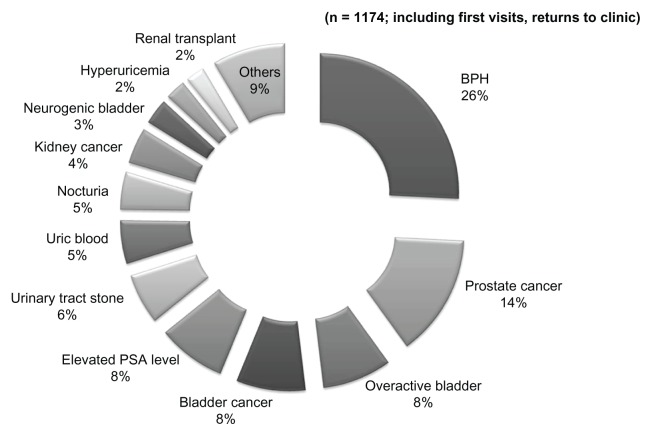

Figure 1 illustrates the demographics of the 1174 subjects. The most common primary disease was prostatic hyperplasia, which was observed in 335 patients (25.8%), followed by prostate cancer in 185 patients (14.2%), OAB in 105 patients (8.1%), bladder cancer in 105 patients (8.1%), and elevated prostate-specific antigen levels in 104 patients (8.0%).

Figure 1.

Diagnosis distribution.

Abbreviations: BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

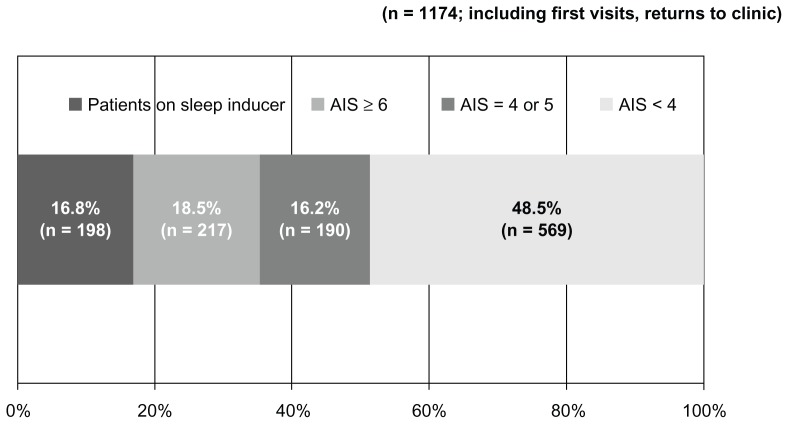

The AIS

Overall, 197 subjects (16.8%) were using sleep inducers; 217 subjects (18.5%) scored ≥ 6 on the AIS, 190 (16.2%) scored 4–5, and 570 (48.5%) scored < 4 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

AIS.

Notes: *Classified according to the total AIS. AIS <4, no suspicion of sleep disorders; AIS = 4 or 5, some suspicion of sleep disorders; AIS ≥6, suspicion of sleep disorders.

Abbreviations: AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale; n, number.

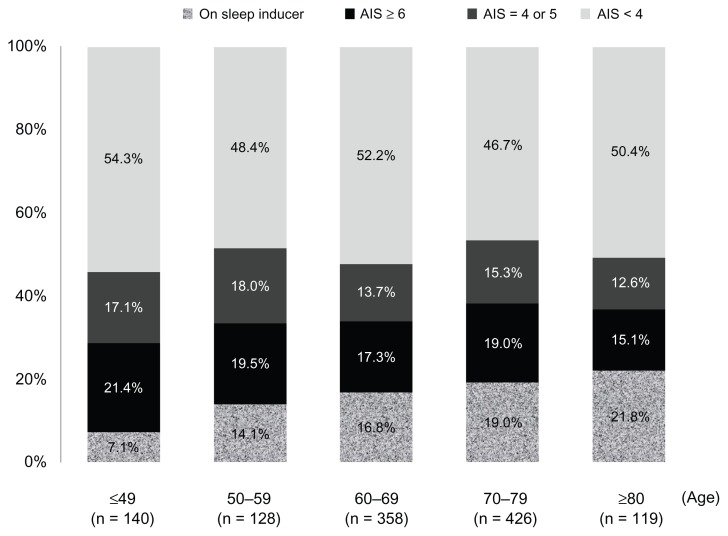

The suspected cases of sleep disorders are classified in Figure 3 into 10-year age groups. Patients on sleep inducers accounted for 7.1% of those aged ≤ 49 years, and their percentage increased to 21.8% among patients aged ≥ 80 years. If patients suspected of having a sleep disorder (ie, an AIS score of 4–5 and ≥6) were combined with those on sleep inducers, then they constituted more than 40% of patients across all age groups (45.7% of patients aged ≤ 49 years, and 49.6% of patients aged ≥ 80 years).

Figure 3.

AIS by age.

Abbreviations: AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale; n, number.

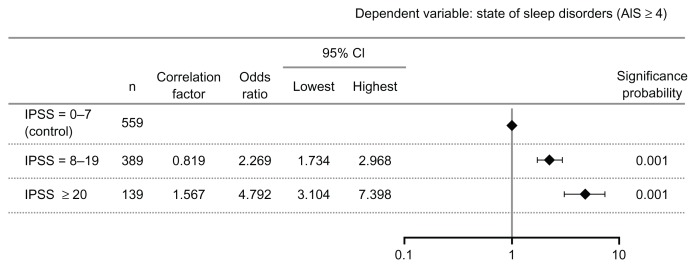

IPSS total score

Based on the IPSS total scores, this risk significantly increased by 2.3-fold among patients with moderate symptoms (scores of 8–19) and by 4.8-fold among those with severe symptoms (scores of ≥20), compared to patients with mild symptoms (scores of 0–7), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Analysis by logistic regression model.

Abbreviations: AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale; n, number; CI, confidence interval; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score.

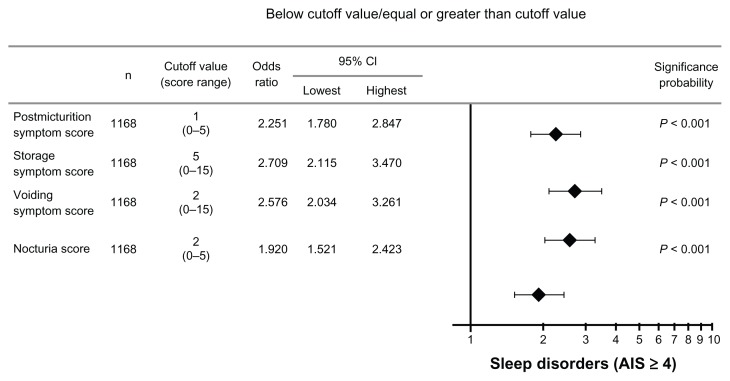

IPSS subscores

An increased risk of suspected sleep disorders was observed among patients with a post-micturition symptom (the feeling of incomplete emptying) subscore of ≥1 (a 2.3-fold increase), a storage symptom (daytime frequency + urgency + nocturia) subscore of ≥5 (a 2.7-fold increase), a voiding symptom (intermittency + slow stream + hesitancy) subscore of ≥2 (a 2.6-fold increase), and a nocturia subscore of ≥2 (a 1.9-fold increase), as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Odds ratio by subscore.

Abbreviations: n, number; CI, confidence interval; AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale.

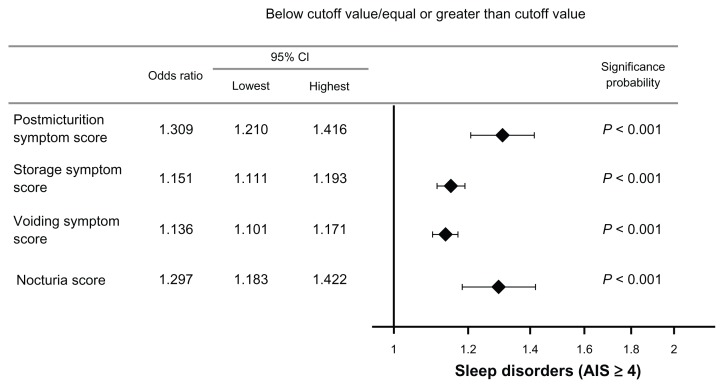

The odds ratio per unit subscore change was calculated at 1.3 for patients with post-micturition symptoms, 1.2 for those with storage symptoms, 1.1 for those with voiding symptoms, and 1.3 for those with nocturia symptoms (Figure 6). The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient suggested a positive correlation between nocturia and post-micturition, storage, and voiding symptom subscores (P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Odds ratio per unit of change in score.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale.

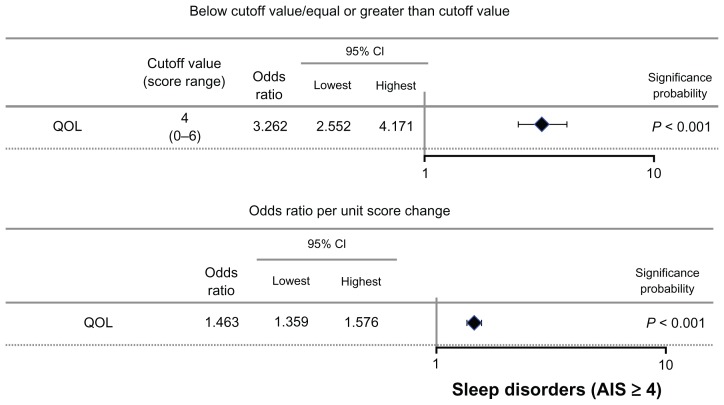

Association between IPSS, QOL, and suspected sleep disorders

The risk for suspected sleep disorders significantly increased by 3.3-fold with a QOL score of ≥4, and the corresponding odds ratio per unit score change was estimated at 1.5 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Association between IPSS, QOL, and sleep disorders.

Abbreviations: QOL, quality of life; CI, confidence interval; AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale.

Discussion

In the present study, our results showed that 16.8% of outpatients treated at urology departments were already using sleep inducers. This suggested that, when combining these patients with suspected cases of sleep disorders characterized by an AIS score of ≥4, 51.5% of patients (or one in two patients) might have developed a sleep disorder as a complication of their disease. This figure exceeded that reported in a previous nationwide study examining the incidence of insomnia complaints in the general population among 3030 subjects who were aged ≥ 20 years, where approximately 30% of subjects aged ≥ 60 years were reported as having a sleep disorder as a complication.1

It is possible that sleep disorders may have been observed in comparatively higher percentages of patients treated at urology departments across all age groups because they have some kind of LUTS. However, the present study did not address the issue of medical complications, which may also cause sleep disorders, and thus further investigations are warranted.

A significant increase in the total IPSS score was observed in patients with moderate (a 2.3-fold increase) and severe symptoms (a 4.8-fold increase), compared to the score of those with mild symptoms. This suggests that there is an association of more severe LUTS with a higher risk of sleep disorders.

Many studies have reported a correlation between sleep disorders and nocturia.3–9 Nocturnal awakening due to nocturia is four times more common than awakening due to pain, which establishes nocturia as a predictor of insomnia and as a factor that influences sleep quality.7 The present study indicates that, in addition to nocturia, other IPSS subscores may act as independent risk factors of sleep disorders. This is demonstrated by the observed 2.3-fold increase in the risk for suspected sleep disorders among patients with a post-micturition symptom subscore of ≥1, the 2.7-fold increase in risk among patients with a storage symptom subscore of ≥5, and the 2.6-fold increase among patients with a voiding symptom subscore of ≥2.

Although the mechanism behind the association between sleep disorders and these symptoms is not clear, long-term insomnia and nocturia are often found to be intricately associated in the elderly. While poor sleep quality may increase arousal during sleep, which results in secondary nocturia, prostatic hyperplasia in men has been reported to cause nocturia,16,17 which in turn leads to a sleep disorder. The present study found a positive correlation between nocturia and post-micturition, storage, and voiding symptom subscores. The severity of LUTS positively correlated with the frequency of nocturia, which may cause sleep disorders. Studies focusing solely on BPH have suggested that sleep disorders are caused not only by nocturia, but also by storage and voiding symptoms. The mechanism underlying the development of such sleep disorders may also involve imbalances in steroid hormone action, sympathetic nervous system activity, and immune dysfunction, which have been considered to potentially contribute to the development of symptomatic BPH and bladder outlet obstruction.18

Some studies have also reported that disruption of the circadian rhythm may contribute to sleep disorders.19,20 The body’s biological clock is involved in regulating bladder function and the amount of urine to be stored over the course of 24 hours, which is important for maintaining secure and sound sleep. Therefore, this mechanism may be involved in the association between LUTS and sleep disorders.21

Although sleep disorders are highly common among patients treated at urology departments, they have not been carefully studied yet. However, treating these sleep disorders will help maintain patients’ level of activity and improve their QOL. It is also possible that improving LUTS may help improve sleep disorders. Therapeutic intervention involving a large number of cases is needed to further understand the association between LUTS and sleep disorders.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. The authors of the present paper have no financial or commercial interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Kim K, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Liu X, Ogihara R. An epidemiological study of insomnia among the Japanese general population. Sleep. 2000;23(1):41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaneita Y, Uchiyama M, Yoshiike N, Ohida T. Associations of usual sleep duration with serum lipid and lipoprotein levels. Sleep. 2008;31(5):645–652. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kageyama T, Kabuto M, Nitta H, et al. Prevalence of nocturia among Japanese adults. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54(3):299–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2000.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asplund R. Nocturia in relation to sleep, somatic diseases and medical treatment in the elderly. BJU Int. 2002;90(6):533–536. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshimura K, Oka Y, Kamoto T, Yoshimura K, Ogawa O. Differences and associations between nocturnal voiding/nocturia and sleep disorders. BJU Int. 2010;106(2):232–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Middelkoop HA, Smide-van den Doel DA, Neven AK, Kamphuisen HA, Springer CP. Subjective sleep characteristics of 1,485 males and females aged 50–93: effects of sex and age, and factors related to self-evaluated quality of sleep. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51(3):M108–M115. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.3.m108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bliwise DL, Foley DJ, Vitiello MV, Ansari FP, Ancoli-Israel S, Walsh JK. Nocturia and disturbed sleep in the elderly. Sleep Med. 2009;10(5):540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gopal M, Sammel MD, Pien G, et al. Investigating the associations between nocturia and sleep disorders in perimenopausal women. J Urol. 2008;180(5):2063–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coyne KS, Zhou Z, Bhattacharyya SK, Thompson CL, Dhawan R, Versi E. The prevalence of nocturia and its effect on health-related quality of life and sleep in a community sample in the USA. BJU Int. 2003;92(9):948–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2003.04527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homma Y, Kakizaki H, Gotoh M, Takei M, Yamanishi T, Hayashi K. Epidemiologic survey on lower urinary tract symptoms in Japan. Nippon Hainyokino Gakkaishi. 2003;14:266–277. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa H, Niu K, Hozawa A, et al. Impact of nocturia on bone fracture and mortality in older individuals: a Japanese longitudinal cohort study. J Urol. 2010;184(4):1413–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupelian V, Fitzgerald MP, Kaplan SA, Norgaard JP, Chiu GR, Rosen RC. Association of nocturia and mortality: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Study. J Urol. 2011;185(2):571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48(6):555–560. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. The diagnostic validity of the Athens Insomnia Scale. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(3):263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. 2nd ed. Rochester, MN: Sleep Disorders Association; 2005. (ICSD-2) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter DJ, Berra-Unamuno A, Martin-Gordo A. Prevalence of urinary symptoms and other urological conditions in Spanish men 50 years old or older. J Urol. 1996;155(6):1965–1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanker MH, Bohnen AM, Groeneveld FP, Bernsen RM, Prins A, Ruud Bosch JL. Normal voiding patterns and determinants of increased diurnal and nocturnal voiding frequency in elderly men. J Urol. 2000;164(4):1201–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cakir OO, McVary KT. LUTS and sleep disorders: emerging risk factor. Curr Urol Rep. 2012;13(6):407–412. doi: 10.1007/s11934-012-0281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zee PC, Mehta R, Turek FW, Blei AT. Portacaval anastomosis disrupts circadian locomotor activity and pineal melatonin rhythms in rats. Brain Res. 1991;560(1–2):17–22. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91209-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steindl PE, Finn B, Bendok B, Rothke S, Zee PC, Blei AT. Disruption of the diurnal rhythm of plasma melatonin in cirrhosis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(4):274–277. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negoro H, Kanematsu A, Doi M, et al. Involvement of urinary bladder Connexin43 and the circadian clock in coordination of diurnal micturition rhythm. Nat Commun. 2012;3:809. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]