Abstract

Innate behaviors have their origins in the specification of neural fates during development. Within Drosophila, BTB (Bric-a-brac,Tramtrack, Broad) domain proteins such as Fruitless are known to play key roles in the neural differentiation underlying such responses. We previously identified a gene, which we have termed jim lovell (lov), encoding a BTB protein with a role in gravity responses. To understand more fully the behavioral roles of this gene we have investigated its function through several approaches. Transcript and protein expression patterns have been examined and behavioral phenotypes of new lov mutations have been characterized. Lov is a nuclear protein, suggesting a role as a transcriptional regulator, as for other BTB proteins. In late embryogenesis, Lov is expressed in many CNS and PNS neurons. An examination of the PNS expression indicates that lov functions in the late specification of several classes of sensory neurons. In particular, only two of the five abdominal lateral chordotonal neurons express Lov, predicting functional variation within this highly similar group. Surprisingly, Lov is also expressed very early in embryogenesis in ways that suggests roles in morphogenetic movements, amnioserosa function and head neurogenesis. The phenotypes of two new lov mutations that delete adjacent non-coding DNA regions are strikingly different suggesting removal of different regulatory elements. In lov47, Lov expression is lost in many embryonic neurons including the two lateral chordotonal neurons. lov47 mutant larvae show feeding and locomotor defects including spontaneous backward movement. Adult lov47 males perform aberrant courtship behavior distinguished by courtship displays that are not directed at the female. lov47 adults also show more defective negative gravitaxis than the previously isolated lov91Y mutant. In contrast, lov66 produces largely normal behavior but severe female sterility associated with ectopic lov expression in the ovary. We propose a negative regulatory role for the DNA deleted in lov66.

Introduction

Understanding the molecular origins of behavioral responses is a central goal of neuroscience. Innate behaviors are a particular focus since these reflexive activities originate in neural circuitry “hard wired” into the organism during development to give robust, invariant responses. As the most intensely studied complex multi-cellular organism, Drosophila offers the best possibilities for understanding the processes by which neural circuitry is laid down in development.

Within Drosophila, the relatively simple larval nervous system, which is formed during embryogenesis, is providing many insights into neurogenesis and neural differentiation. The critical role of transcription factor cascades has emerged from studies of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), where major components of the transcriptional hierarchies that give rise to various classes of sensory neurons have been identified (reviewed in [1], [2]). Similarly, gene profiling of the CNS midline cells has identified cell-type specific signatures of transcription factor expression [3], [4], whose roles in neural specification is being confirmed by genetic studies [5], [6]. However, many further steps in the processes leading to final differentiation of individual neurons remain to be identified.

Through a screen for defective responses to gravity, we previously identified CG16778 as a neurally expressed gene that influences behavioral responses [7]. We have named the gene jim lovell (lov) in honor of this astronaut’s pioneering work in microgravity. lov encodes a putative transcription factor of the BTB/POZ domain family. These proteins contain a ∼120 amino acid domain, initially identified in the Drosophila proteins Bric-a-brac, Tramtrack and Broad [8] and in Poxvirus zinc finger proteins [9], that acts as a protein-protein interaction module mediating homo- and hetero-dimer formation and sometimes higher order oligomerization in various family members. Lov belongs to the more closely related tramtrack (ttk) subgroup [10] that has a BTB/POZ domain with three distinct regions of high conservation [11]. Fruitless, the master regulator for male courtship behavior, is also a ttk subgroup member [12]. Most of the Drosophila ttk proteins are known/putative transcription factors containing a zinc finger DNA binding domain. However, Lov belongs to a smaller subset consisting of Pipsqueak, Ribbon, Bric-a-brac, Pielke, and three uncharacterized proteins, that all contain a modified helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain termed the pipsqueak domain [11], [13]. These conserved domains thus suggest roles for lov in transcription regulation mediated via protein-protein interactions. Based on a partial cDNA sequence for CG16778, the gene was initially proposed to belong to the tyrosine kinase family and was named Tyrosine-kinase related (Tkr) [14]. Given that the protein does not function as a kinase, the authors of that previous study have agreed to the name change we propose here (H. Jackle, personal communication). CG16778 was also identified as gene BTB III in a study aimed at identifying BTB-containing genes in Drosophila [15].

We present here an investigation of lov function based on analysis of its expression and on study of new lov mutants derived from our initial gravitactic mutant, lov91Y. These studies show that lov is widely expressed in the embryonic nervous system and indicate a role in the late development of some sensory neurons, potentially producing distinctions in the properties of closely related neurons within a given class. We also demonstrate that lov is essential for proper execution of several innate behaviors - ranging from coordinated locomotor responses in larvae to negative gravitactic climbing and male courtship behavior in adults. We further provide evidence that lov has non-neural roles in early embryonic pattern formation and in the testis.

Materials and Methods

Mutation Generation by Imprecise Excision

Deletion mutations lov38, lov47 and lov66 were generated by mobilizing the w+ P{GawB} [16] insertion of lov91Y [7] with the Δ2–3 transposase at 99B [17]. Standard genetic crosses were used to generate lines of w− viable mutations. Each deletion was initially identified by genomic PCR and the precise endpoints for each deletion were determined by sequencing appropriate PCR fragments.

Fly Stocks and Genetics

Deficiency SB1 (also known as Df(2R)Kr10), which removes the entire lov locus [18], was obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) in stock 4961. For behavioral analysis, mutations lov38, lov47, lov66, lov91Y and deficiency SB1 were all isogenized by six rounds of outcrossing to a w+; Sco/CyO stock. SB1 and lov66, which cannot be maintained as homozygous stocks, are carried over the CyO chromosome from this w+; Sco/CyO stock. Stock 5702 (w−; Sco/CyO-GFP) from BDSC was used to generate lov47/CyO-GFP and lov66/CyO-GFP lines for larval and embryo analysis, respectively. For ectopic expression of lov, the following GAL4 drivers were obtained from BDSC: (GAL4::VP16-nos.UTR) CG6325MVD1 (stock 4937), P{GawB}c204 (stock 3751), P{GawB}c355 (stock 3750) and P{GawB}c532 (stock 30841).

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was prepared from various tissues or life cycle stages using Trizol lysis as described in [19]. cDNA was prepared using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and a random hexamer mix (New England Biolabs). For detection of processed lov transcripts, the primer 5′ TCAACTTCTGGTGGGCGTCCTTTA 3′, which is the reverse complement of residues 41–64 of the first common exon of the four lov transcripts, was paired with primers specific for the immediate upstream 5′UTR exon of each transcript (see below). PCR (30 cycles) at appropriate annealing temperatures was then used to generate fragments specific for each lov mRNA. Primers for transcripts from the ubiquitously expressed Actin gene at 57B were used to standardize output for analysis. Fragments were detected after agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Primer sequences were as follows.

Transcript A - 5′ ATCCGAGTGTCATCTTCAACGCGA 3′.

Transcript B - 5′ ACATACGCTCATTCGTTACCCGCT 3′.

Transcript C - 5′ TGTCTTGAACAGAACTATATTGTG 3′.

Transcript D - 5′ GTTTCCAAAGAAGCAATCAAACGGC 3′.

Actin 57B forward –5′ TTCCAAGCCGTACACACCGTAACT 3′.

Actin 57B reverse –5′ TCATCACCGACGTACGAGTCCTTCT 3′.

Antibody Generation

A 218 amino acid region of the lov coding sequence with no detectable similarity to any other protein sequence in the Drosophila genome was chosen for antibody generation. This region lies within the first protein coding exon (common to all four transcripts), 948 residues downstream of the ATG start site and 270 residues downstream of the BTB domain (Figure 1). Primers (5′ CTGGAAGTTCTGTTCCAGGGGCCCCTGGGATCC 3′ and 5′ GAATTCCCGGGTC GACTCGAGCGGCCGCAT 3′) that add an upstream BamH I site and downstream EcoR I site were used to generate the required PCR fragment from lov cDNA clone GH08221 (Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project) for CG16778. After initial cloning into pCR4-TOPO (Invitrogen), the coding region was transferred to expression vector pGEX-6P-1 as a BamH I/EcoR I fragment, to generate a GST-lov fused coding sequence. After induction, fusion protein was collected on a glutathione column. The Lov region was released by cleavage with PreScission Protease (GE Life Sciences) and used to raise antibodies in a rabbit and a guinea pig (Cocalico Biologicals, Inc). The recombinant Lov protein fragment cross-linked to NHS-activated Sepharose resin (GE Life Sciences) was used for affinity purification.

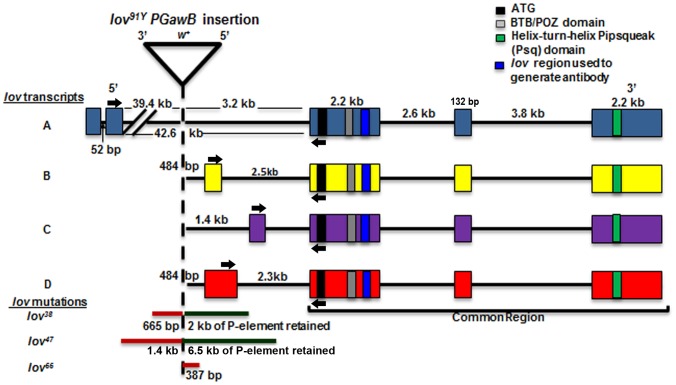

Figure 1. Transcripts and mutations of the Drosophila jim lovell locus.

The exon structure of the four lov transcripts is shown. The three common exons encode the same BTB/POZ domain protein. Structural motifs of the protein and the region used to prepare antibodies are indicated. Arrows indicate the positions of the primers used to probe for expression of the four transcripts. The original lov91Y P{GawB} insertion and three deletion mutations (lov38, lov47 and lov66) generated by imprecise excision of the transposon are shown.

UAS-lov Construct

The entire lov protein coding sequence in cDNA clone GH08221 was amplified using primers (5′ GTTGAATTCCTGGATACGAGAATTGAAGCACGC 3′ and 5′ GTTAGATCTGTTTCAATCATGCCCGGTC 3′) that add an upstream EcoR I site and a downstream Xho I site. The resulting PCR fragment was cloned into these two sites in the pUAST vector [16] using standard cloning techniques. The Lov protein sequence within the final construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Transgenic animals were generated by GenetiVision (Houston) and homozygous viable lines carrying single copies of the construct on each of the major chromosomes were prepared by standard genetic procedures. A line carrying UAS-lov on the second chromosome was used here.

Embryo Immunostaining

Standard procedures were used to collect embryos and then to dechorionate and fix them in 3% paraformaldehyde and to remove their vitelline membranes. Embryos were stored at −20°C in methanol prior to staining. After rehydration in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), embryos were blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS and then stained with primary antibodies. Antibodies used were as follows: guinea pig anti-Lov 1∶500, rabbit anti-Lov 1∶200, mouse 22C10 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) 1∶200. For single labeling, biotin-labeled secondary antibodies (Vector Labs, 1∶500 dilution) were used, followed by streptavidin-horse radish peroxidase (Pierce) and detection via metal-enhanced 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) treatment (Pierce). For double labeling with anti-Lov and 22C10, alkaline phosphatase (AP) labeled anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Promega, 1∶500 dilution) were also applied and detected with an X-phosphate nitroblue tetrazolium detection kit (Vector labs). For examination of lov66/lov66 embryos, a lov66/CyO-GFP stock was used. Embryos were co-stained with anti-GFP peptide antibody (Clontech Laboratories, Inc, 1∶500 dilution) and anti-Lov antibody to identify lov66 homozygous embryos.

Hatch Rate Determinations and Egg Shell Analysis

Males and virgin females 3–6 days of age were set up in egg lay dishes over small Petri dishes containing grape juice agar smeared with yeast paste. 12–15 male-female pairs were used per egg lay dish. After discarding the initial plate, 100 eggs were collected from each of three successive overnight collections. The eggs were arrayed in a 10×10 grid on a new plate and after 36 hours, the number of unhatched eggs was counted. For each male/female combination tested, at least two separate sets of mating pairs were set up to give at least six estimates of egg hatch rate. For eggshell analysis, after preparing a 10×10 grid of eggs, eggshells and dorsal appendages were scored and classified as described in the text.

Larval Locomotion and Food Shoveling Assays

Assays were modified from the protocols described by Neckameyer [20]. Four-hour egg lays were collected using egg lay dishes as described above. For locomotor assays, 24 hours later, batches of 30 newly hatched larvae were transferred to grape plates covered with 2.0 grams of yeast paste (40% w/v dry yeast powder). 72 (+/−2) hours after egg laying, larvae were washed free of food using fine Nitex meshes and transferred in batches onto 2% agar plates in preparation for assays. Individual larvae were then placed on a fresh 2% agar plate, allowed one minute to acclimatize and then the number of locomotor contraction waves (strides) in one minute was counted. In all genotypes but lov47, only forward strides were seen. But in lov47, trains of backward strides were also detected. To quantitate this effect, any larva showing three or more consecutive backward locomotor strides was scored as showing spontaneous backward movement. For food shoveling assays, newly hatched first instar larvae were collected from egg lay plates, and placed on 2% agar plates for one hour prior to assay. Individual larvae were then transferred to a 2% agar plate coated with a layer of 2% w/v yeast paste. After a minute of acclimatization, the number of mouth hook contractions (shovels) in one minute was scored. lov66 homozygous larvae were collected from the lov66/CyO-GFP stock based on lack of GFP fluorescence. At least 100 larvae of each genotype were tested in each assay.

Adult Climb Tests

Newly eclosed males were placed in individual food vials and aged for two days. Each was then transferred to an empty food vial with a circumferential marking line 5 cm from the base of the vial. The fly was then tapped gently to the bottom of the vial and the time to climb to the 5 cm mark was recorded. Each fly was tested 10 times with a one-minute rest period between tests. Any trial in which a fly failed to reach the 5 cm line in one minute was scored as a climb failure. At least 50 adults of each genotype were tested.

Male Courtship and Activity Assays

Courtship assays were modified from the protocol described previously [7]. Newly eclosed naïve males were collected and aged individually in food vials for 7 days before testing with single virgin 3–5 day old Canton-S control females. Wheel-type courtship chambers were used [7]. Flies were transferred to the chambers without anesthetization. Behavior was video-recorded and the amount of time each male spent performing any element of the courtship ritual (orienting to the female, tapping, wing extension, licking, and attempting copulation) in a 10 minute interval was determined. Two Courtship Indices (C.I.s) were calculated. The “directed” C.I. was calculated as the fraction of total time spent performing these rituals towards the female. The “non-directed” C.I. was calculated as the fraction of time preforming courtship elements not focused on the female. At least 10 males were tested for each genotype. General locomotor activity was determined for males alone in the courtship chambers by positioning a black line under the chamber at its diameter and determining how many times the male crossed the line in a 10 minute period. At least 25 males were tested for each genotype.

Results

The Multiple Transcripts of lov Show Tissue and Developmental Stage Specific Expression

The structure of the lov locus as predicted by Flybase in 2008 is shown in Figure 1. The four lov transcripts all generate the same protein encoded by three common 3′ exons of the gene. However, three different promoters are used and although transcripts B and D share a promoter, transcript D contains 5′ UTR sequences not present in transcript B. Thus unique 5′ non-coding sequences are present in each of the mRNAs. The transcript B/D promoter and C promoters are close to the protein coding exons, whereas the promoter for transcript A is remote, lying ∼ 43 kb upstream of the first protein coding exon. We used Semi-quantitative (Semi-Q) RT-PCR to investigate the expression patterns of the transcripts. A primer from the first protein coding exon was paired with transcript-specific primers derived from the non-coding 5′exons of the individual mRNAs so as to generate PCR fragments for each of the final four mRNAs. Figures 2 and 3 show the tissue distribution of the transcripts in adults and their developmental expression patterns, respectively.

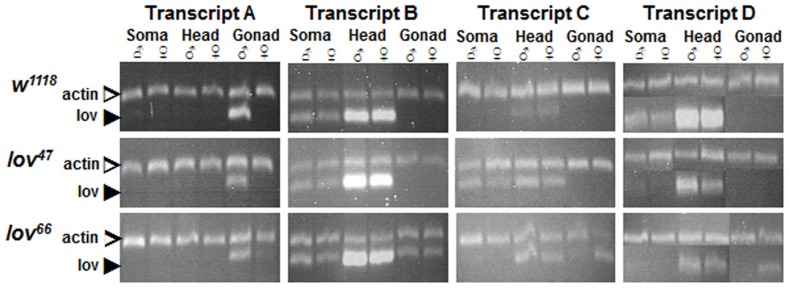

Figure 2. Tissue specific expression of the lov transcripts in adults.

Semi-Q RT-PCR was used to detect lov transcripts in the bodies (soma), heads and gonads of male and female adults from a control (w1118) strain and lov47 and lov66 mutant lines. Primers as indicated in Figure 1. In all cases, the fragments amplified span intron-exon boundaries to limit detection to mature transcripts. A fragment from the ubiquitous Actin mRNA (Actin at 57B) was amplified in parallel as the control. At least two separate RNA preparations for each tissue were used for transcript quantitation. The PCR fragment for transcript D was very close in size to the Actin PCR fragment. To quantitate this transcript, aliquots of separate transcript D and Actin PCR reactions for each RNA sample were run in parallel in separate gel lanes.

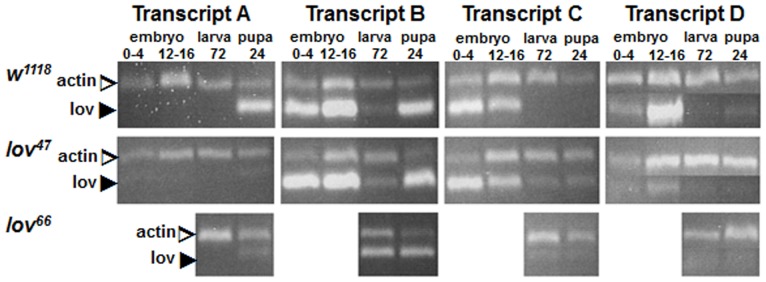

Figure 3. Developmental expression of the lov transcripts.

Semi-Q RT-PCR, as described for Figure 2, was used to detect lov transcripts in embryos 0–4 and 12–16 hours after egg laying (AEL), larvae 72 hours AEL, and pupae 24 hours after pupation from control (w1118) and lov47 and lov66 mutant flies. lov66 is maintained as a balanced (lov66/CyO) stock (see text) and transcripts for homozygous lov66 embryos could not be reliably evaluated. At least two separate RNA preparations for each stage were used for transcript quantitation.

The various transcripts show strikingly different expression profiles. Transcript A is testis-specific and transcript C is almost entirely limited in expression to the early stages of embryogenesis. Transcripts B and D, which share a transcription start site, show considerable overlap in their expression patterns. Both are more strongly expressed in the adult head rather than the soma, suggesting that they have neural roles. However both are also expressed in the early embryo along with transcript C indicating non-neural functions in early development, as described below. Transcript D appears to be the dominant neural transcript since it shows a greater differential presence in adult head versus soma than transcript B. Further, it shows much stronger expression in late embryos, during the neural developmental stages, than transcript B. As described below, the late embryonic expression of Lov is entirely neural. During the larval stages, very little lov transcription is detected and Lov protein expression in the nervous system fades away. But as the remodeling of the pupal stages begins, transcript B expression is again expressed (Figure 3) and Lov protein becomes detectable within proliferating CNS neurons (data not shown).

During the course of our work, transcript A, which was originally part of the Flybase description of the gene, was removed by the Flybase curators. However our Semi-Q RT-PCR experiments, in which we probed for processed mRNAs from the locus, establish that transcript A is indeed expressed in the organism as a testis-specific transcript (Figure 2). This transcript is first detected in early pupal stages as the male gonad begins its final development (Figure 3). Recent work indicates that lov transcription in the testis is regulated by wake-up-call, a lin-52 paralog [21].

Embryonic Lov Protein Expression Suggests Distinct Roles in Early Pattern Formation and in Neural Differentiation

To examine Lov protein expression we generated polyclonal antibodies against a unique protein-coding region (Figure 1) in rabbit and guinea pig and subjected them to affinity purification. We were able to confirm the specificity of these antibodies for protein immunolocalization in three separate ways. First, as predicted, Lov immunostaining is nuclear and the nuclear patterns correspond well to cytoplasmic in situ hybridization patterns for lov mRNA probes described previously [14], [15]. Second the antibodies stain every neural nucleus after ectopic expression of Lov protein throughout the embryonic nervous system using the elav GAL4 driver and a UAST-lov construct [22]. Finally, one of our lov mutations (lov47) results in loss of elements of the antibody immunostaining from components of the nervous system (see below).

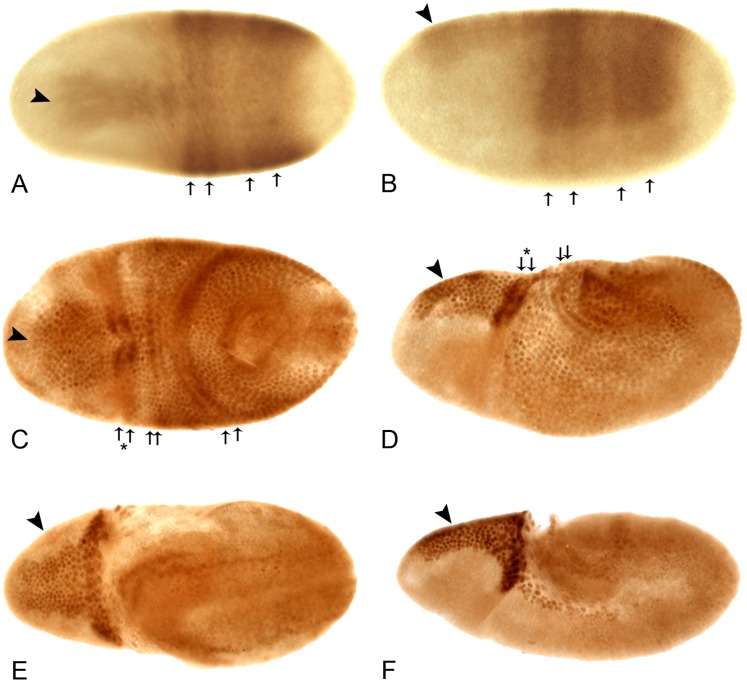

We have focused on the pattern of Lov protein expression during embryogenesis. Our RT-PCR experiments reveal a pronounced shift in lov mRNA expression, from transcript C to transcripts B and D, as embryogenesis progresses (see above). These changes are associated with two distinct phases of Lov expression: an early non-neural phase and a later phase associated with differentiation of the CNS and PNS. The early pattern is shown in Figure 4. The newly laid egg contains no Lov protein, in agreement with the absence of lov mRNA in the ovary (Figure 2). At cellular blastoderm, Lov appears in two distinct regions. A “wedge” of Lov protein spanning the anterior dorsal midline appears simultaneously with a broad “saddle” of expression, also across the dorsal midline, that stretches from ∼10–50% along the egg length and around ∼60% of the embryonic circumference (Figure 4 A, B). This saddle contains two prominent dark stripes at its anterior edge separated from a second pair of more diffuse dark stripes, of which the most posterior is significantly broader. The narrow pointed region of the wedge of Lov expression can also be seen to contain two or three darker stripes.

Figure 4. The early embryonic expression pattern of Lov protein.

All embryos are anterior to left. A, C, and E - views of the dorsal surface; B, D, and F - lateral views, dorsal uppermost. At cellular blastoderm (A, B) Lov staining appears across the dorsal midline as an anterior “wedge” (arrowhead) and a “saddle” of two pairs of diffuse stripes (arrows) at ∼10–50% egg length. In early germ band extension (C, D), staining in the wedge intensifies (arrowhead) and the diffuse saddle stripes (arrows) sharpen into paired rows of nuclei spanning the positions of ectodermal folds (see text). A further pair of rows of nuclei staining for Lov across the dorsal midline develops at the edges of the cephalic furrow (arrows and asterisk). The staining in these rows is particularly intense where they traverse the wedge of Lov stain. In late germ band extension (E, F), the wedge staining (arrowheads) can be seen to lie within the procephalic neuroectoderm. Intense staining is also seen in the polyploid nuclei of the amnioserosa at its junction with the cephalic furrow and in its lateral longitudinal extensions. In E, paired rows of Lov staining nuclei are also seen at the periphery of the extending germ band.

As germ band extension begins, the diffuse stripes within the wedge and saddle sharpen into discrete pairs of rows of cells with darkly staining nuclei (Figure 4 C, D). These rows correspond to the opposing edges of the folds in the dorsal ectoderm generated by germ band extension: these folds are the cephalic furrow, the anterior and posterior transverse ectodermal folds and the amnioproctodeal invagination. The staining in the pair of rows at the edge of the cephalic furrow is particularly intense. Cells at the edges of the embryonic folds may have special properties such as enhanced rigidity and Lov may in someway contribute to these characteristics. Lov expression in the remainder of the wedge also intensifies and becomes recognizable as lying within the procephalic neuroectoderm (pne) region, the source of many brain neurons. At full germ band extension, Lov is expressed in the dorsolateral ectoderm and in another pair of highly staining rows of cells around the periphery of the extended germ band (Figure 4 E). These cells are again positioned at the edges of dynamic folds and may also need mechanical reinforcement. Finally strong staining appears in the developing amnioserosa. This structure, which forms from cells between the tip of the extended germ band and the dorsal region of the cephalic furrow has roles in dorsal closure and germ band movement. The strongest staining in the embryo at full germ band extension is in the pne (Figure 4 F), where presumptive proneural cells are closely apposed to a band of strongly staining polyploid amnioserosal cells lining the cephalic furrow.

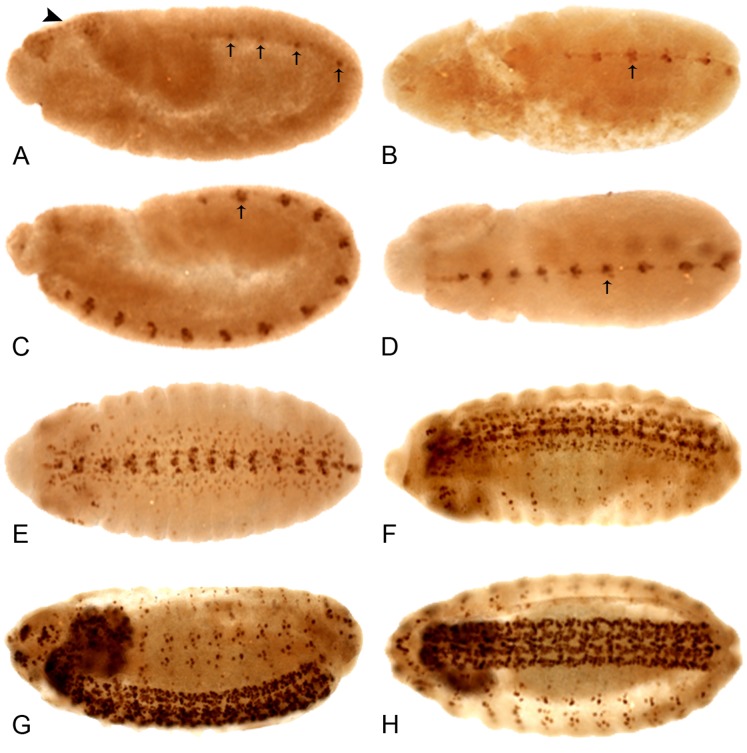

After full germ band extension, Lov staining disappears and the embryo is briefly devoid of Lov expression. But as segregation of neuroblasts from the ectoderm begins, a second phase of expression is initiated. A single nucleus in the midline of each developing thoracic and abdominal segment begins Lov expression (Figure 5 A). Further Lov positive CNS nuclei both at the midline and more laterally in the ventral nerve cord (VNC) appear during germ band retraction (Figure 5 B–D) so that a pattern dominated at first by nuclei at the positions of the longitudinal connectives is formed followed by a pattern with two additional longitudinal strong bands of nuclei at the lateral edges of the VNC. Lov-positive nuclei connecting these bands also develop such that the late Lov CNS staining has a mesh-like appearance (Figure 5 D–F). Using in situ hybridization, the Crews lab has previously characterized lov mRNA expression in CNS midline cells and other components of the CNS and PNS at later stages [3], [4]. Our Lov immunolocalizations match in nuclear protein staining the cytoplasmic lov transcript patterns detected in the Crews lab.

Figure 5. The late embryonic expression pattern of Lov protein.

All embryos are anterior to the left. A, C, and G - lateral views, dorsal uppermost; B, D, E–H - dorsal views. At the end of germ band extension (A) the early Lov pattern (Figure 4) disappears and a single nucleus at the midline of each parasegment begins to express Lov. As germ band retraction proceeds (B–D), more nuclei at the developing CNS midline express Lov. Nuclei in the lateral regions of the CNS (E) the brain lobes (E, F) and along the longitudinal connectives (F) develop staining as germ band retraction is completed and dorsal closure begins. PNS staining is first detected in early dorsal closure (F). At ∼ stage 15, CNS and PNS staining are maximal (G, H) and CNS staining has a mesh-like appearance (H).

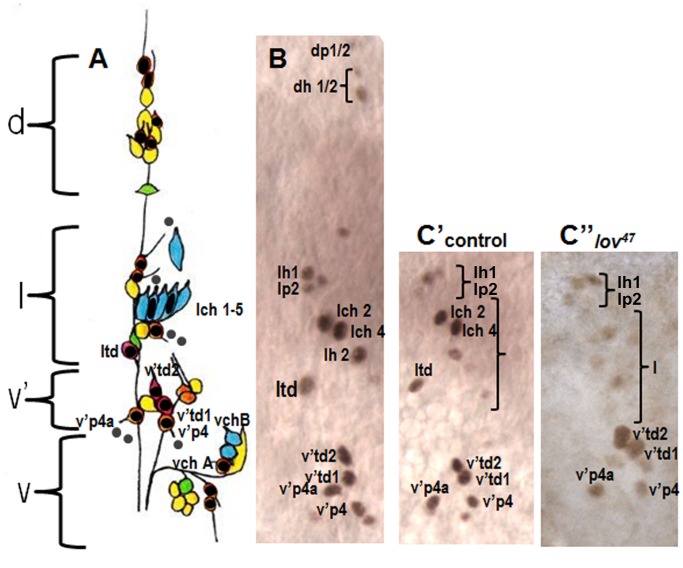

Although great progress in identifying the neuronal sub-types within the embryonic CNS has been made [23], at this point the PNS of the embryonic abdominal segments is better characterized, with four clusters of neurons (dorsal, lateral, ventral and ventral’) showing a highly stereotypical pattern in each hemisegment [24]. We therefore focused on analyzing Lov expression in these segments as a means of gaining insight into Lov’s roles in neural development. PNS Lov staining is not detected until after germ band retraction and initiation of dorsal closure, that is, as the final neurons of the PNS are developing and beginning terminal differentiation. A single darkly staining nucleus first appears in the lateral cluster, rapidly followed by groups of nuclei in all four clusters. The number of Lov-positive nuclei and the overall Lov staining intensity increases as dorsal closure proceeds such that stage 15 represents a point of maximal expression. We used co-staining with antibody 22C10, which stains all sensory neurons [25], to identify the PNS nuclei expressing Lov at this stage. Almost all stained nuclei are neuronal although faint staining was detected in some non-neuronal cells. From their positions we deduce that these are support cells in the external sense organ neural lineages. Figure 6 A shows a diagram of the sensory neurons in a typical abdominal hemisegment, indicating all nuclei identified as Lov-positive. Figure 6 B shows the actual ∼stage 15 Lov staining pattern in a single hemisegment for the dorsal, lateral and ventral’ clusters.

Figure 6. Lov expression in the embryonic abdominal PNS.

A - a cartoon of the four clusters (dorsal (d), lateral (l), ventral’ (v′) and ventral (v)) of sensory neurons within each hemisegment of the abdominal segments (redrawn from [2]). Neurons are color coded according to class as follows: orange - external sense organ, pink - tracheal dendrite, blue - chordotonal, yellow - dendritic arborization, green - bipolar dendritic. Key neurons discussed in the text are labeled. Neuronal nuclei expressing Lov (shown by black dots or ovals) were identified in embryos co-stained with anti-Lov and 22C10. Grey dots = putative non-neuronal support cell nuclei that express low levels of Lov. Nomenclature for all neurons as in [24] except that the neurons of the lateral chordotonal organ are labeled lch1-5. B - Actual example of wild type Lov-staining nuclei at stage 15 in clusters d, l, and v′ of a single abdominal hemisegment. C - anti-Lov (brown) and 22C10 (blue) costaining of the lateral chordotonal organ in a control embryo to demonstrate Lov limitation to lch2 and lch4. D - 22C10 staining of a lov47 homozygous embryo demonstrating the presence of all five chordotonal neurons in the lateral chordotonal organ. E′, E′′ - loss of Lov staining in chordotonal organ neurons lch2 and 4 of a lov47 mutant embryo. E′ shows control staining in clusters l and v′. E′′ shows staining in equivalent regions of a lov47 embryo. Loss of staining in td neuron ltd is also seen in this lov47 embryo.

Five classes of sensory neurons are present in the abdominal PNS; external sense organ (eso) neurons, chordotonal (ch) neurons and three classes of multiple dendritic neurons – the dendritic arborization (da), bipolar dendritic (bp) and tracheal dendrite (td) classes. With the possible exception of one da class cell (Figure 6 A), Lov is not expressed in any neurons of the bp or da classes. All three td neurons show strong nuclear staining and almost all eso class nuclei are also Lov positive, although some stain quite weakly and no staining was ever detected in two eso neurons of the ventral’ cluster. Strikingly, of the eight chordotonal organ neurons present per hemisegment, six showed no Lov expression, but two express Lov strongly. These are neurons 2 and 4 of the lateral pentascolopale organ (lch 2 and 4 where lch 1 is the nearest neuron to the intersegmental nerve) (Figure 6 C). The nucleus of neuron 2 of this cluster is the first peripheral neuron to begin expressing Lov (see above). Lov expression is thus not limited to any particular class of PNS neurons and is not expressed in all members of the classes in which it is expressed.

At stage 15, the nuclei of lch2 and 4 together with the two td neurons of the ventral’ cluster show the strongest Lov staining. In the final stages of embryogenesis and immediately before cuticle formation, these four nuclei are often the only peripheral neurons retaining Lov expression, creating a distinctive pattern of four dots in each abdominal segment.

Phenotypes Associated with Deletion Mutations of the lov Locus

We identified a single mutation to the lov locus (lov91Y) as part of a screen for mutations that affect gravity responses in Drosophila [7]. The P{GawB} element associated with lov91Y is inserted close to the transcription start sites for the B, C and D lov mRNAs and within the large intron of the A transcript. Imprecise excision of the lov91Y transposon generated three mutations that delete genomic DNA from the locus (Figure 1). lov38 and lov47 delete sequences upstream of the lov91Y insertion point, with the lov38 deletion lying entirely within the 1.4 kb lov47 deletion. In contrast, lov66 deletes ∼400 bp of DNA downstream of the lov91Y transposon. The mutations thus delete intronic or flanking DNA not present in any final transcripts, with lov38 and lov47 deleting overlapping DNA that is distinct from that of the lov66 deletion.

All three of the new deletion mutations produce viable adults with normal external morphology suggesting that any phenotypic defects are limited to behavior and/or reproductive processes rather than developmental events. As a consequence of their origins as imprecise excisions of the w+ P{GawB} transposon of lov91Y, these new mutations were initially in a w− background. To allow comparisons to lov91Y and avoid possible effects of the w − background on adult behavior [26], the new mutations and lov91Y were all subjected to serial outcrossing to put them into the same w+ background. All of the studies described here were performed with mutant lines in this genetic background.

Loss of lov expression in lov47 leads to defects in larval locomotion and feeding and adult locomotion and courtship

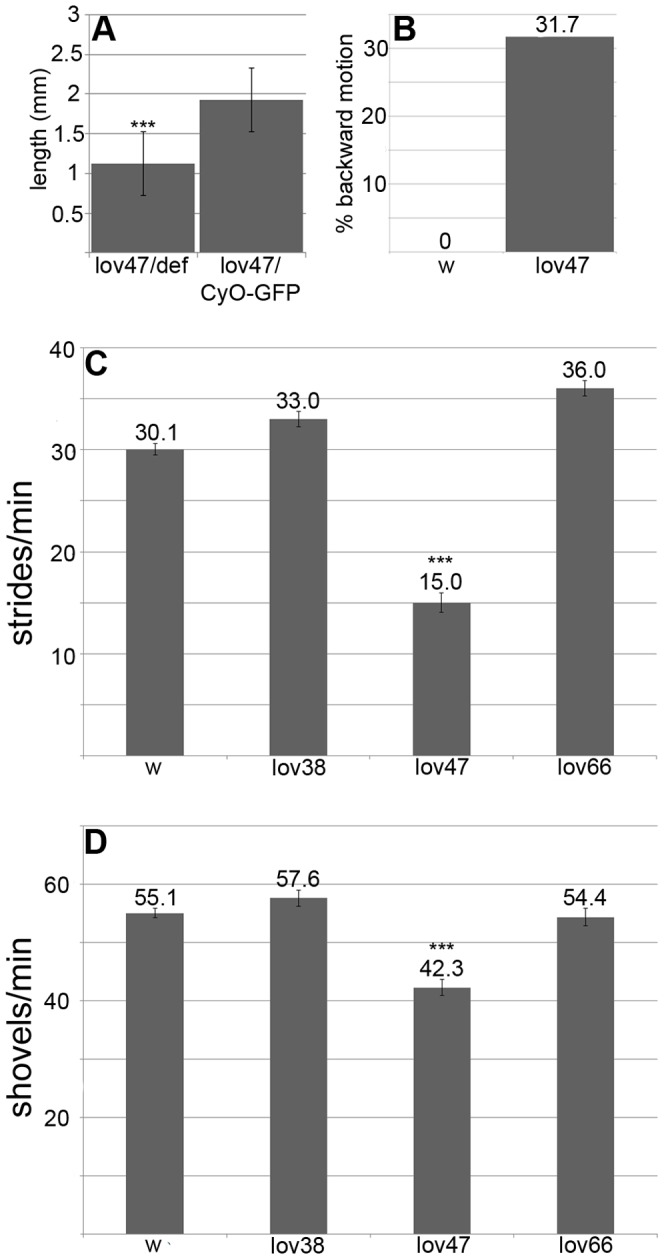

Although lov47 homozygous and hemizygous females are highly fertile in terms of eggs laid and egg hatch rate (Figure 7), the resulting larvae show delayed development and poor growth. Fewer individuals survive to adulthood and surviving adults are often reduced in size. Even when fed on a diet of pure yeast paste, lov47 larvae are significantly smaller than Canton-S controls (Figure 8 A). We detected two behavioral defects in the larvae that could contribute to this poor growth. From hatching onwards lov47 larvae are sluggish, showing less than half the locomotor activity of controls (Figure 8 C). Locomotion is also often deregulated. Whereas wild type larvae only show reflexive backward movements in response to contact with obstacles or noxious stimuli, 32 out of 101 lov47 larvae show bouts of spontaneous avoidance of this type in the absence of any obvious trigger (Figure 8 B). Feeding activity, as assessed by counting the rate of mouth hook movement associated with food shoveling, is also depressed (Figure 8 D). Given that reduced feeding could result from decreased chemosensory input from food, we investigated food-related sensory capacity in these larvae. Although lov47 larvae are slow to respond in taste tests, due to their decreased mobility, their preference for sucrose versus sucrose laced with caffeine (a repellent stimulus) is indistinguishable from wild type (data not shown) and they show a normal preference for fructose (a strongly attractant stimulus) versus lactose (a non-stimulating sugar [27])(Figure S1). These data suggest that poor motor control rather than reduced food sensing could underlie the “failure to thrive” of lov47 larvae.

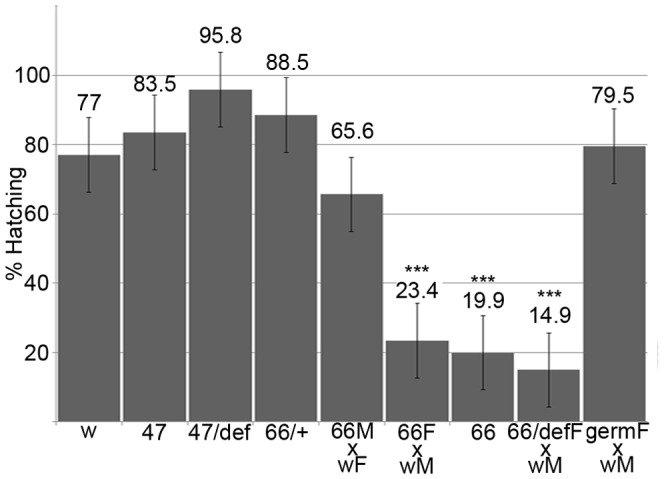

Figure 7. Hatch rates for eggs from lov47, lov66 and related genotypes.

Batches of eggs from stocks or crosses of the genotypes indicated were collected and scored for hatching as described in Material and Methods. w = w1118, 47 = lov47, 66 = lov66, def = lov deficiency chromosome SB1,+ = CyO balancer, germ = UAS-lov in the ovarian germline under the GAL4 driver P (GAL4::VP16-nos.UTR) CG6325MVD1. M = male, F = female. Hatch rates for the lov66/CyO stock and the lov47/def stock were adjusted to correct for death of CyO/CyO and def/def homozygotes. At least six separate collections, totaling at least 600 eggs, were scored for each genotype. One way Anova and a Dunnett’s test were used to determine statistical significance *** = p<0.001 compared to w1118.

Figure 8. Growth and behavioral defects in lov47 larvae.

A - poor growth of lov47 larvae in rich medium. lov47 hemizygous (lov47/def) and heterozygous (lov47/CyO-GFP) larvae from a lov47/CyO-GFP stock grown on yeast paste were sorted based on GFP fluorescence at 87 hours AEL and imaged under a dissecting microscope with a length gauge, after brief ether anesthetization. B - percentage of larvae at 72 hours AEL showing backward locomotion (as defined in Material and Methods) for lov47 and w1118 (w). C - forward locomotion rates at 72 hours AEL for w1118, lov38, lov47, and lov66 homozygous larvae. D - food shoveling rates at 72 hours AEL for larval genotypes as in C. Statistics as for Figure 7. *** = significantly decreased (p<0.001) as compared to w1118.

The early embryonic Lov expression pattern is normal in lov47, but major defects in the late neural expression precede the behavioral problems seen in lov47 larvae. Expression of lov transcript D during neural differentiation is highly suppressed (Figure 3) and Lov staining is missing from many neurons in both the CNS and PNS. In the abdominal PNS, staining with the panneural antibody 22C10 established that the relevant neurons were present but no longer expressing Lov (Figure 6 D). We also established that the mutation has differential effects on Lov expression amongst the various Lov staining neurons identified. For most of the eso neurons and tracheal neurons, v′td1 and v′td2, Lov expression is not dramatically altered. But strikingly, expression in lch2 and 4 is absent in most segments (Figure 6 E′, E′′). Thus, the lov47 deletion appears to specifically affect regulatory elements that direct expression in these neurons.

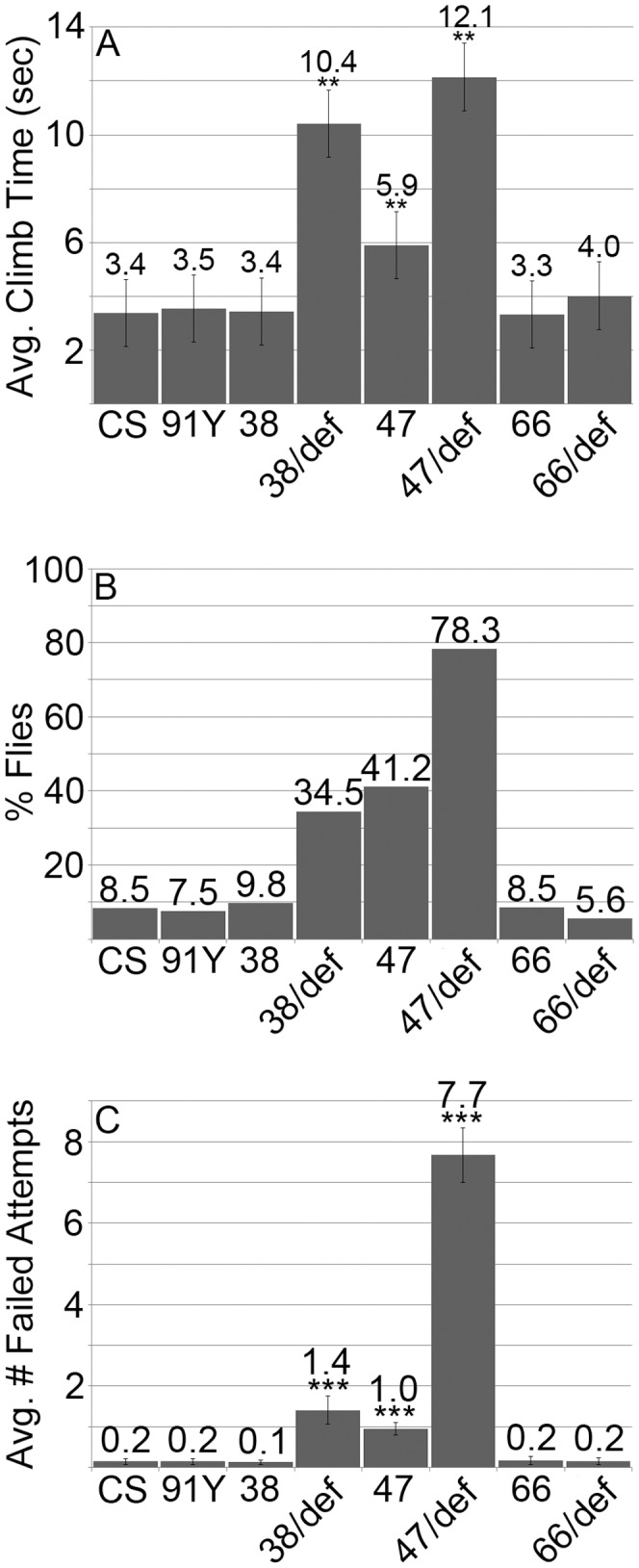

lov47 adults were tested for responses to light, attractive and repellent tastes, repellent odors and water. Their responses in these assays were essentially wild type (Figures S2–S5) suggesting, as for lov47 larvae, that many sensory pathways are intact. However, two major behavioral defects were detected. When assayed in a negative gravitactic climb test, lov47 homozygous and hemizygous adults showed two defects. For flies that completed climb assays, the climb rate was slower than for controls, with lov47 hemizygotes taking three times as long to complete the 5 cm climb, as a result of pausing and non-upward movement (Figure 9 A). But in addition, lov47 mutant flies showed a failure to complete climb tests, either from failure to initiate climbing or cessation of climbing during the assay. Each individual fly was sequentially tested 10 times and ∼40% of homozygotes, ∼80% of hemizygotes, failed to complete the climb in at least one of these repetitions (Figure 9 B). The average percentage of failed climbs per fly for hemizygotes was particularly high (76%, Figure 9 C). lov47 hemizygous adults showed poor viability, typically dying within five days of eclosion.

Figure 9. Negative gravitactic defects in lov38 and lov47 adults.

A - Climb times in the negative gravitactic climb assay (see Material and Methods) for flies of each genotype that completed the climb in less than one minute. B - Percentage of flies of each genotype that failed to complete the climb in at least one trial. C - The average number of failed climbs for the 10 consecutive trials performed for each fly. CS = Canton-S, 91Y = lov91Y, 38 = lov38, 47 = lov47, 66 = lov66, def - lov deficiency chromosome SB1. Statistics as previously. ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001 as compared to CS.

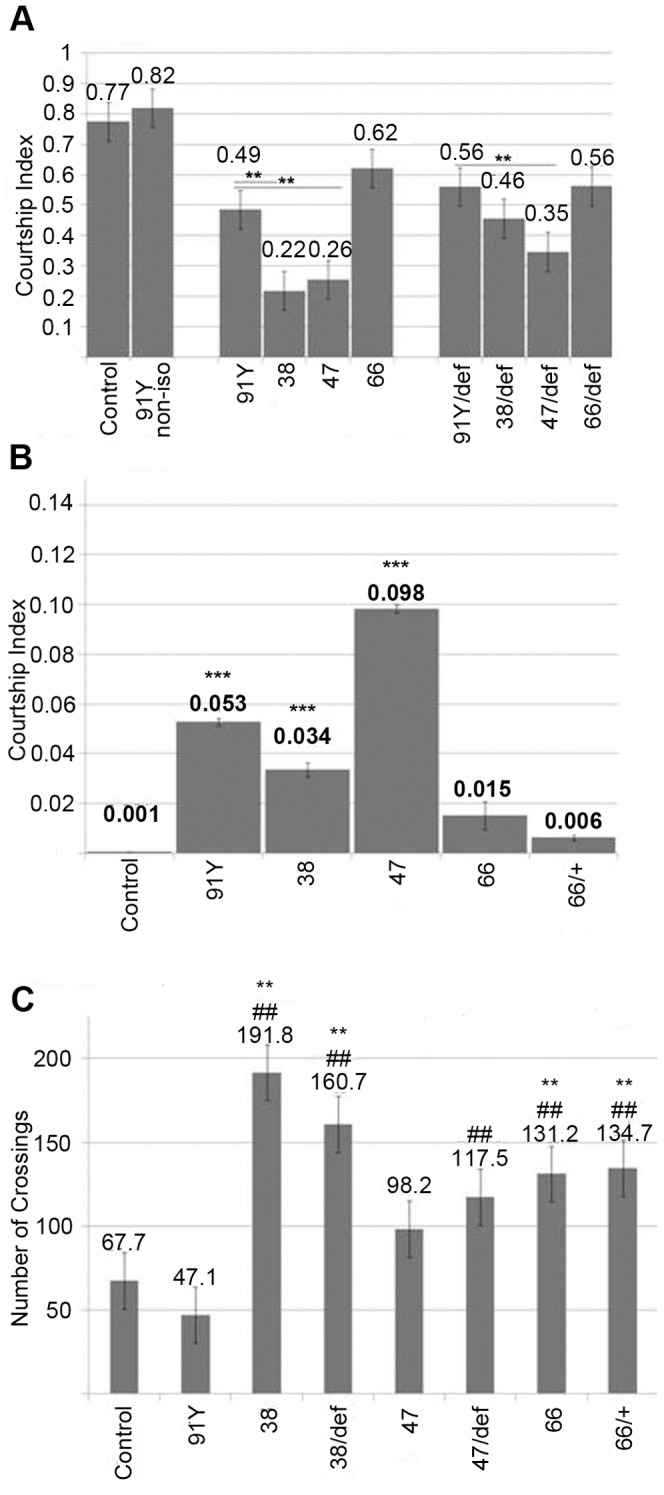

lov47 males also showed strong defects in male courtship. Normal courtship was significantly lower than for males of the parent lov91Y genotype, which showed wild type courtship in its original genetic background (see legend Figure 10 A). In addition, lov47 males showed “non-directed” courtship, performing elements of the courtship ritual without focusing their behavior on the female. This was particularly true of wing extension. Males could be seen wandering around the courtship chamber rather than pursuing the female, performing wing extension as they did so. Separate Courtship Indices for “directed” (Figure 10 A) and “non-directed” courtship (Figure 10 B) were calculated for lov47 and other genotypes. These revealed a low level of non-directed courtship for the parent lov91Y chromosome and for the related lov38 deletion (Figure 10 B and see below). Further, this quantitation established that for lov47, almost 30% of total courtship activity is of the “non-directed” type (Figures 10 A, B). Due to their poor viability, only a limited number of lov47 hemizygous males could be tested for courtship at seven days of age. These males tended to be immobile in the presence of females and non-directed courtship was largely replaced by “passive” courtship, where males would only execute elements of the courtship routine if the female came very close. However, a generalized defect in locomotion was not a factor in lowering the courtship index for these males. Activity assays performed in the courtship chambers in the absence of females revealed that both lov47 hemizygotes and homozygotes were at least as active, if not more so, than controls (Figure 10 C).

Figure 10. Courtship defects in lov38 and lov47 males.

A - Directed courtship. Courtship indices for courtship directed towards the female. The courtship indices for lov91Y in its original genetic background (91Y non-iso) and after isogenization of lov91Y into the same w+ background (see text) as the other lov mutants (91Y) are shown. Comparison of these two indices demonstrates that the new genetic background suppresses courtship significantly. Courtship behavior for lov38, lov47 and lov66 is therefore compared only to the lov91Y iso line (91Y) to correct for this background suppression of courtship. Statistics as previously. ** = p<0.01 as compared to isogenized lov91Y. B - Non-directed courtship. Courtship indices for elements of the courtship ritual performed while not pursuing the female. Statistics as previously. *** = p<0.001 as compared to Canton-S control. C - Locomotor activity for males alone in courtship chambers (see Material and Methods). Control - Canton-S, 91Y = lov91Y, 38 = lov38, 47 = lov47, 66 = lov66,+ = CyO chromosome, def - lov deficiency chromosome SB1. Statistics as previously. ** = p<0.01 as compared to Canton-S control. ## = p<0.01 as compared to isogenized lov91Y.

lov38 mutants show adult behavioral phenotypes similar to those of lov47

The deletion associated with lov38 is contained within the lov47 deletion, sharing the same downstream breakpoint as lov47. Unlike lov47, lov38 does not affect the late embryonic expression pattern of Lov protein and lov38 mutant larvae appeared and behaved like controls (Figure 8 C, D). However, lov38 does show adult phenotypes similar to those of lov47. Male courtship is decreased to levels comparable to those seen for lov47 males (Figure 10 A) and is accompanied by the same kind of non-directed courtship activities (Figure 10 B). lov38 also fails to complement the lov47 defects in male courtship (data not shown). lov38 adults show poor climbing ability although the defects are not as marked as those of lov47 (Figure 9). However, the general locomotor activity shown by lov38 males when alone in the courtship chamber is significantly higher than that of lov47 males (Figure 10 C).

lov66 is a neomorphic mutation affecting oogenesis

In lov66, a different region of the locus is deleted than in lov38 and lov47 and the phenotypic consequences are markedly different: lov66 produces female sterility (Figure S6). Eggs from homozygous or hemizygous lov66 mothers have a low hatch rate (∼20%) irrespective of mating partner genotype ( Figure 7 ) and the mutation has to be maintained as a balanced stock. Hoechst staining established that ∼80% of the unhatched eggs showed no development and were apparently unfertilized. This lack of development did not correlate with problems in mating or sperm storage since lov66 homozygous females are courted by Canton-S males as vigorously as Canton-S females (data not shown) and after mating, lov66 females carry stored sperm in their seminal receptacles as frequently as controls (Table S1).

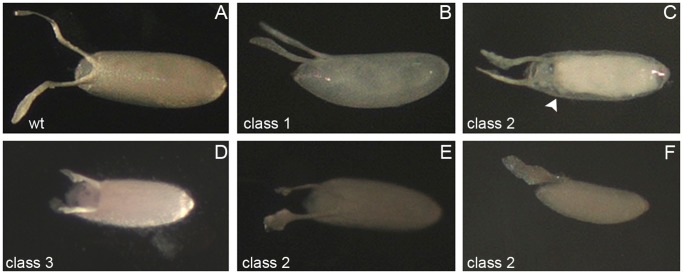

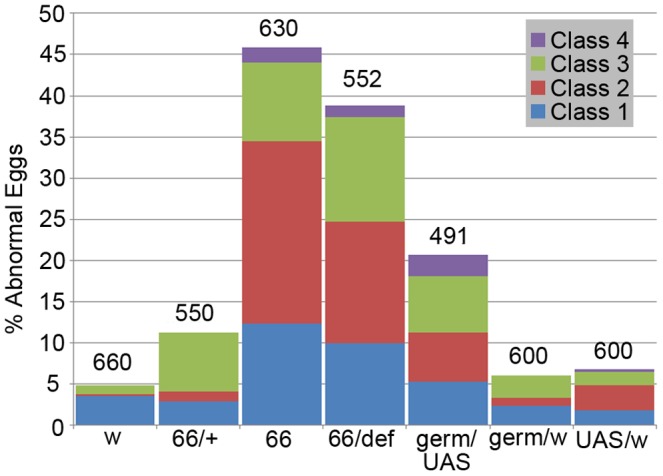

Eggs from lov66 homozygous or hemizygous mothers show a range of defects. Some aberrant eggs (Class 1, Figure 11) were of normal shape and size, but had a transparent, thin eggshell (chorion) and dorsal appendages (DAs) and were typically somewhat flaccid. This phenotype has been well described [28] and illustrated previously (compare Figure 1 B of Schwed et al. [29] with Figure 11 B) and results from failure to amplify or express chorion protein genes late in oogenesis [30], [31]. However, in addition to a thin chorion, some eggs also showed defects in the final stages of egg morphogenesis (Class 2, Figure 11). Aberrantly shaped DAs were seen, often on eggs showing failed formation of the anterior-most dorsal structures of the eggshell. These eggs often appeared unsealed at the anterior and absorbed color from the grape plates used for egg collections. Late in oogenesis the germline nurse cells “dump” their cytoplasmic contents into the oocyte proper. For lov66, eggs in which the chorion appeared to seal off the nurse cell compartment prematurely and prevent complete dumping were identified (Figure 11 C). A further abnormal egg class (Class 3, Figure 11) consisted of short eggs with sealed eggshells showing a characteristic cup-shaped indentation at the position of the operculum flanked by two stubby branched DAs. In most cases the chorion and DAs on these eggs were thick and opaque; a few short eggs of this type also showed the transparent chorion/DA phenomenon and were categorized as Class 2 eggs. Finally a small number of eggs appeared otherwise normal except for aberrantly shaped DAs (Class 4).

Figure 11. Classes of abnormal eggs produced by lov66 mothers.

A - wild type egg with opaque chorion and two opaque dorsal appendages (DAs). B-F - examples of abnormal eggs from lov66 homozyous or hemizygous mothers. B - class 1 egg (see text) with translucent chorion and translucent, weak DAs. C - class 2 egg (see text). DAs are abnormal and translucent and formation of the anterior chorion has failed. Illuminated to show chorion-like barrier (arrow) that has prevented complete nurse cell dumping. D - class 3 egg. Chorion is opaque and thick but egg is short, with stubby DAs. E, F - class 2 short, flaccid eggs with translucent chorions and translucent abnormal DAs.

An analysis of oogenesis established that defects in egg chamber formation for lov66 mothers were limited to the late stages of oogenesis. Follicles prior to the vitellogenic stages appeared morphologically normal and markers for specialized somatic cells associated with the follicles, such as the stalk and polar cells, showed that these cells were present in normal numbers and at their normal positions (data not shown). However, abnormalities consistent with the defects seen in laid eggs were detected during the vitellogenic and later stages, including malformed DAs and incomplete nurse cell dumping associated with premature formation of a chorion-like structure between the nurse cells and oocyte proper. Overall, these findings show that lov66 affects late events in egg morphogenesis including aberrant activity of the somatic cells that form the chorion and associated structures.

These defects were surprising given that we could not detect either lov transcripts (Figure 2) or Lov protein in wild type egg chambers. RT-PCR analysis of lov transcript expression in the lov66 mutation resolved this discrepancy. As shown in Figure 2, in contrast to the control situation, all four lov mRNAs are detectable in the lov66 ovary. Thus the lov66 ovarian phenotype involves ectopic expression of lov in this tissue. To determine if deliberate ectopic expression of lov in the germline or somatic follicle cells of the egg chambers could produce effects comparable to lov66, we used the GAL4-UAS system [16] to drive lov expression in both cell types. We found that expression of lov in the female germline using the GAL4 driver P(GAL4::V P16-nos.UTR) CG6325MVD1 [32] reproduced the lov66 phenotype. Although a lower fraction of the eggs were abnormal (Figure 12), qualitatively the same range of aberrant egg phenotypes was produced by GAL4::V P16-nos.UTR) CG6325MVD1/UAS-lov mothers. The quantitative difference could reflect a lower level of ectopic lov expression than that seen with lov66 itself. We tested three GAL4 follicle cell drivers, c532 [33], c204 and c355 [34] in an attempt to determine whether ectopic lov expression in the somatic cells also affects egg development but, presumably as a result of ectopic expression of lov in other tissues, these crosses produced essentially no adult survivors making meaningful analysis impossible.

Figure 12. Abnormal egg production in lov66-related genotypes.

The percentage of abnormal eggs of various classes (see text) is shown for lov66 homozygous (66), heterozygous (66/+ = 66/CyO), and hemizygous mothers (66/def), for mothers (germ/UAS) expressing UAS-lov ectopically in the ovarian germ-line under the GAL4 driver P (GAL4::VP16-nos.UTR) CG6325MVD1 and for appropriate control mothers (w = w1118, germ/w and UAS/w). All females were mated to w1118 males. Numbers of eggs examined for each genotype are shown above the bars.

We deduce that these lov66-associated maternal effects on oogenesis result from the ectopic expression of lov in the ovary. However, surprisingly, whereas lov66 hemizygous mothers show comparable maternal effects on hatch rate and eggshell defects (Figures 7, 12), eggs from lov66 heterozygous mothers (lov66/CyO) have largely normal egg cases and show normal hatch rates. This finding, which may indicate a transvection effect at the locus (see Discussion), allowed us to assess the effects of the lov66 mutation on embryonic viability in the absence of the lov66 maternal effect. As shown in Figure 7, lov66/CyO × lov66/CyO crosses have an essentially wild type hatch rate, when corrected for the death of CyO/CyO progeny, indicating that lov66/lov66 embryos are viable. To determine whether, like lov47, lov66 affects the zygotic Lov protein expression pattern we examined lov66 embryos from a lov66/CyO-GFP stock. Given that GFP expression from the balancer chromosome develops slowly, we could only reliably examine the later neural expression of Lov. In contrast to lov47 embryos, lov66 embryos showed no loss in Lov expression in the PNS or major changes in CNS expression (data not shown). The resultant larvae grew as well as controls when selected from the balanced CyO-GFP stock and grown as homozygotes in yeast paste. These larvae also showed none of the larval behavioral defects associated with the lov47 mutation (Figure 8). When lov66/CyO stocks were grown in uncrowded conditions, lov66 homozygous adults emerged in the expected ratio (that is 2 lov66/CyO : 1 lov66/lov66) but the number of emergent lov66 homozygotes dropped considerably in crowded conditions, suggesting some growth disadvantage in the presence of heterozygous siblings. The lower expression of lov transcript B during larval and early pupal life (Figure 3) may contribute to this effect.

lov66 homozygous adults were subjected to the same array of behavioral tests as lov47 and lov38 and showed none of the behavioral problems seen for those mutants. Climbing behavior and male courtship were comparable to controls (Figures 9 and 10) and lov66 males were essentially normal in the sensory assays we performed (Figures S2–S5), with the exception of a statistically significantly slight reduction in response to sucrose as a tastant (Figure S3).

Discussion

The Lov Early Embryonic Expression Pattern

The early Lov staining pattern suggests roles for the protein in three aspects of early embryogenesis. The intense staining in rows of cells that form the boundaries of transient folds in the ectoderm may indicate that Lov functions to promote the mechanical properties of these cells, supporting their role in global re-structuring of the embryo. The strong staining in the dorsal head region, which spans the procephalic neural ectoderm, suggests a role in determination of neural lineages within the head. Finally, the early expression in the amnioserosa could signify a role for Lov in the early differentiation of this extraembryonic tissue and thus its function in dorsal closure and germ band retraction [35], [36]. None of the mutations characterized here is a null and none of them affects these early expression elements. Experiments with lov RNAi are therefore being used to address the functions of these early patterns.

By comparing the Lov expression pattern to that of other early acting genes, we have identified loci that may be upstream regulators of lov, or act in parallel with it, during these early stages. The three highly-related Dorsocross proteins, which all have the same expression pattern, show a strikingly similar distribution to Lov at stage 8, with the same strong head and amnioserosal staining [37]. This set of proteins does not show the stripe elements seen for Lov at cellular blastoderm but the mRNA expression patterns for pannier (pnr) [38], which encodes a GATA transcription factor [39] and for a gene encoding the serotonin receptor 5HT2 [40] both consist of broad saddles of stripes across the dorsal midline that overlap the Lov saddle along the anterior/posterior axis. Interestingly the 5HT2 receptor has already been shown to play a role in transverse furrow formation in the ectoderm during germ band extension [41]. pnr and the Dorsocross genes are both required for formation of the amniserosa and are regulated by decapentaplegic (dpp) and zernknullt (zen), which act early in the formation of the dorsal embryonic tissues. Both the Zen protein [42] the dpp mRNA pattern [43] also show intense staining in cells at the boundaries of the transient ectodermal folds, as seen with Lov, suggesting that these early acting regulators also control the Lov pattern. The stripe component of the early Lov pattern evokes comparisons to the pair rule and segment polarity genes, whose roles in early pattern formation entail expression in distinct stripes along the anterior-posterior axis [44]. The striped expression of the serotonin receptor 5HT2 is already known to be regulated by the pair rule gene fushi tarazi (ftz) and its ubiquitously expressed cofactor, ftz-F1 [45]. We plan epistatic analyses to determine the position of lov in these early genetic hierarchies.

The Lov Abdominal PNS Expression Pattern

The timing and expression pattern of Lov in the PNS indicates that lov acts late in neural development to direct final neuronal differentiation of subsets of neurons. Given the expression pattern of Lov within the various classes of sensory neurons, we can predict some elements of the transcriptional hierarchies that regulate lov in the PNS. Thus the lov expression in most eso neurons indicates that lov is activated downstream of achaete and scute, the proneural genes of the achaete-scute complex (ASC) that direct formation of the eso mother cells [46] and downstream of cut, which maintains the “eso” identity in the mother cell lineage [47]. The da class of multiple dendritic neurons, which does not express Lov, also derives from these lineages [48] and so additional regulators must act to prevent lov expression in these neurons. Similarly the absence of Lov in the bp multiple dendritic class suggests suppression of lov by amos, the proneural regulator of this class [49].

The expression pattern of Lov within the chordotonal lineages indicates considerable complexity in lov regulation. Limitation of Lov expression to two neurons of the ch class (neurons 2 and 4 of the lateral chordotonal five-neuron cluster) is a striking finding. To our knowledge this is a unique observation that suggests for the first time functional differences amongst the five chordotonal organs (CHOs) at this site. Developmentally, these CHOs are already known to originate via two distinct pathways [50]. Initially, three chordotonal precursors are formed under the direction of the proneural gene atonal [50], [51]. Subsequently rhomboid expression in these precursors leads to EGF receptor signaling, induction of argos in adjacent cells, and formation of two further chordotonal precursors. It is not known precisely which of the final five lateral CHOs correspond to the two derived from the second phase of development but one possibility is that they are the two Lov expressing neurons. Lov expression would thus be downstream of both atonal and EGF signaling in these neurons.

One of the two CHOs of the ventral cluster (VchA) is also induced by the later wave of EGF signaling activity [50], but we find that neither of the two ventral CHOs (VchA and B) expresses Lov, indicating different regulatory mechanisms when compared to lch2 and 4. Further, both the VchA and VchB neurons undergo an additional cell division to generate the two md tracheal neurons td1 and td 2 [48]. These neurons, in contrast to their sibling VchA and VchB neurons, express Lov strongly. Generation of these varying Lov expression patterns within the CHO lineages clearly requires a multiplicity of regulatory mechanisms.

The analyses of lov mRNA expression in the midline lineages performed previously [3]–[6] indicate that regulation of lov within the CNS is also dynamic and complex and that here too lov has roles in the final differentiation of particular neuronal sub-types. The single cell per segment that first expresses Lov protein in the CNS (Figure 5) has been identified by the Crews lab as one of the eight primordial midline precursor cells whose determination is controlled by singleminded. Through stages 11–17 of embryogenesis lov mRNA is transiently expressed in the posterior midline glia, the median neuroblast (MNB) cell and a subset of ventral unpaired median motorneurons (VUMs) to give a final expression pattern at stage 17 in just three neurons: a single cell of the MNB progeny and the sister interneuron and motor neuron derived from division of midline precursor neuron 6 (MP6). Notch and lethal-of-scute act at various points to regulate these expression patterns [5], [6].

The lov47 and lov66 Phenotypes Reflect Loss of Different Transcription Regulatory Elements

The lov47 and lov66 mutations produce strikingly different phenotypes, with lov47 mutants showing multiple behavioral defects and lov66 mutants proving behaviorally unexceptional but strongly female sterile. These differences indicate that the mutually exclusive, non-coding, DNA sequences deleted in the two mutations have differing regulatory roles for the individual lov transcripts. Some of the effects on individual transcripts produced by each mutation generate the differing phenotypes detected here but other effects are without consequence, at least in terms of the traits we assayed. Thus the DNA deleted in lov47 has a strong positive role in production of lov transcript D, a lesser positive role in production of transcript A and a negative role in production of transcript C (Figures 2 and 3), but the phenotypic effects detected here all appear to have their origins in the loss of transcript D alone. Interestingly, transcript B, which has the same transcription start site and expression pattern as transcript D, is not affected by the deletion. It is possible therefore that the embryonic neurons retaining Lov expression in the lov47 mutant are neurons that express transcript B as opposed to transcript D.

We hypothesize that a global repressor of lov transcript expression in the female gonad is deleted in the lov66 mutation and the main phenotypic consequences of this mutation result from loss of this DNA. The deleted DNA also contributes in a positive way to expression of transcripts A, B and D in various tissues and stages (Figures 2 and 3). Due to the female sterility, we did not examine transcript D levels in late embryogenesis for lov66 by RT-PCR, but Lov protein expression appeared normal in these stages. However, in adults, lov66 depresses neural transcript D expression even more strongly than lov47. Given their marked differences in terms of behavioral consequences, we conclude that the two mutations affect transcript D expression in different subsets of adult neurons. As discussed below, a component of the lov66 induced female sterility may result from loss of lov expression in neurons controlling the female genitalia that are unaffected by lov47.

The lov47 Behavioral Phenotypes

The larval phenotypes identified for lov47 are defects in motor functions: the rates of food shoveling responses and forward locomotion are significantly decreased. The Crews lab has shown that loss of the ventral nerve cord midline neurons, which includes lov expressing cells, results in sluggish larval forward motion [5], suggesting that this lov47 phenotype originates in the CNS. But lov47 larvae also show bouts of backward locomotion, which are normally a stimulus-elicited avoidance response. A Central Pattern Generator (CPG) within the CNS coordinates the rhythmic locomotor contraction waves of the larval body wall and prior work has shown that loss of sensory input from the periphery disrupts CPG performance, producing both decreased forward, and spontaneous backward, contraction waves [52]. Caldwell and Eberl have further provided evidence that most of this peripheral sensory feedback to the CPG derives from the chordotonal neurons of the PNS [53]. Thus, the specific loss of Lov expression in two of the five lateral chordotonal organ neurons in lov47 could diminish sensory feedback to the CPG and contribute to abnormal backward movement.

Motor defects are also seen in lov47 adults. The defective lov47 gravitactic climb responses cannot be considered a consequence of general sluggishness since lov47 adults show enhanced locomotor activity when alone in courtship chambers. They appear to represent a more severe form of the diminished negative gravitaxis produced by the original lov91Y mutation. Thus the original lov91Y mutant has normal climb behavior (Figure 9 and [7]) and its decreased negative responses to gravity are only uncovered in the gravitactic maze assay [7]. Like the lov47 larval locomotor defects, the lov47 defective gravity responses could also reflect loss of lov function in chordotonal neurons. Although the enhancer trap P{GawB} insertion of lov91Y does not show GAL4 expression in Johnston’s organ, a major graviperceptor organ in the antenna, GAL4 is expressed in the adult leg femoral chordotonal organ (data not shown), another proprioceptor organ with a demonstrated role in gravity responses in other insects (reviewed in [54]). Thus, the loss of negative gravitaxis in adult lov47 mutants could reflect deletion of enhancer sequences adjacent to the lov91Y P{GawB} insertion point that promote lov expression in the femoral chordotonal organ.

The larval defects of lov47 indicate loss of central organization of locomotor responses. The aberrant courtship responses of lov47 males reinforce this concept of failed coordination of innate responses. Male courtship is highly stereotypic with a series of ordered steps (following the female, tapping her, wing vibration, licking the female) leading to abdomen curling and copulation. lov47 males showed a marked inability to pursue females continuously but still performed non-directed wing extension, and occasionally abdomen curling, often towards the courtship chamber walls. As noted earlier, Lov belongs to a class of putative transcription factors that includes Fruitless (Fru), the master regulator of male courtship behavior. Given that this class of transcriptional regulators is known to form homo- and hetero-dimers, it is tempting to speculate that Lov might affect courtship responses through protein-protein interaction with Fru. We have not yet attempted a detailed analysis of Lov protein expression in the adult head but preliminary experiments indicate that Lov is expressed in a very large number of adult CNS neurons, a subset of which also express Fru (data not shown).

The lov66 Neomorphic Phenotype

The lov66 induced female sterility appears to represent a neomorphic phenotype resulting, at least in part, from ectopic expression of lov in the ovarian germline. However, some aspects of our data for this phenotype are puzzling. First, although lov66 hemizygotes show the same phenotype as homozygotes, lov66 heterozygotes are essentially wild type both with respect to eggshell features and egg hatch rate (Figures 7 and 12). Given that the single copy of the mutant chromosome present in both hemizygotes and heterozygotes should be capable of deregulated lov expression, this result is unexpected. The two genotypes differ however in the state of the lov locus on the homolog paired with the lov66 chromosome. In hemizygotes, the entire locus is missing whereas in heterozygotes the presumed regulatory DNA is present on the homolog and could regulate expression from the lov66 chromosome via transvection. Recently transvection has been shown to be a common regulatory mechanism in Drosophila [55], supporting this possibility.

A further puzzling comparison involves the hatch rates and eggshell defects associated with lov66 homozygous/hemizygous mothers and mothers expressing UAS-lov under the ovarian germline GAL4 driver. Whereas for mothers expressing UAS-lov in the germline, the fraction of aberrant eggs (20%) correlates well with the fraction of unhatched eggs (20%), for lov66 mothers, the fraction of unhatched eggs (∼80%) is significantly higher than the fraction of detectably abnormal eggs (∼45%). Given that the unhatched eggs from lov66 mutant mothers appear undeveloped and unfertilized, one possible explanation is that lov66 can disrupt egg maturation and fertilization through a second route, involving other elements of the female reproductive system. Adult females lacking the midline CNS neuron population (which includes lov expressing neurons) show sterility thought to reflect loss of innervation of the female genitalia, perhaps producing failed fertilization [5]. It is possible that lov66 causes loss of elements of lov CNS expression in addition to producing ectopic ovarian expression.

Mechanistically, ectopic expression of lov in the ovary must be presumed to produce interference with the action of one or more factors active in eggshell synthesis and morphogenesis. Making the simplest assumption that a single factor is affected by Lov to produce both phenotypes, we sought to identify regulators that affect both eggshell synthesis and eggshell morphogenesis and for which action in the follicle cells is controlled by signals from the germline. Two transcriptional regulators, Broad [33], [56] and Tramtrack [57]–[59], meet these criteria. Interestingly these are both BTB transcriptional regulators, offering the possibility, as discussed for Fruitless above, that Lov misregulates function by direct protein interaction. For both Broad and Tramtrack, there is evidence that expression and/or action in the somatic follicle cells is controlled by ecdysone signaling from the germline [58]–[60]. Further, mutation of broad and dominant interference with ecdysone signaling produce eggshell phenotypes similar to those seen with lov66. In particular i) the fragile chorions and short/malformed/branched DAs from mothers mutant for the rbp class of broad mutations [56] are similar to the eggs from lov66 mothers and ii) the short eggs with stubby DAs and cupshaped dorsal anteriors produced by dominant negative inhibition of ecdysone receptor function in the follicle cells, or loss of ecdysone production, are like the Class 3 eggs identified for lov66 [61]. These findings suggest that the neomorphic action of Lov in the ovarian germline affects ecdysone signaling and that downstream effects on follicle cell function include disruption of the action of Broad. Although we have not pursued the underlying mechanism of this neomorphic lov66 phenotype in detail, we have determined that, in ovaries from lov66 mothers, effects on broad are not limited to effects at the level of protein/protein interaction. broad transcription is depressed in lov66 ovaries in addition to disruption of Broad protein localization (Figure S7). Depression of broad expression is consistent with the depressed broad expression seen on loss of ecdysone signaling.

Note Added in Proof

In addition to lacking transcript A (RA), the Flybase page for CG16778 now shows a new minor lov transcript (transcript RE), which was not studied here and which contains additional 3′ protein coding sequences.

Supporting Information

lov47 larvae show normal taste responses to sugars. Petri dishes filled with two adjacent semicircles of 1% agarose gel, one with 10% fructose (strongly attractant) and red food coloring and the other with 10% lactose (non-stimulating) and blue food coloring, were used to test larval sugar preference. Twenty-five larvae, collected 65 hours after egg laying, were placed on the boundary between the two sugars and the number of larvae at the boundary and on each of the two sugar semicircles was counted after 5, 10 and 15 minutes. The experiment was repeated eight times (200 larvae of each genotype total) and mean values with standard error for all eight repeats are shown. A. Control Canton-S larvae. B. lov47 larvae. Although lov47 larvae take longer to move to the compartment of their choice, their preference for fructose at 15 minutes is indistinguishable from that of the controls. Error bars represent standard error. Assay modified from Xu et al., Nature Neuroscience 11, 676–682, 2008 and Schipanski et al., Chem. Senses 33, 563–573, 2008.

(DOCX)

lov mutants show normal responses in a fast phototaxis assay. The various lov mutants were tested for their ability to detect and respond to light. Flies were placed in a t-test apparatus in which one tube was exposed to a light source and one tube remained in the dark. The flies were allowed one minute to choose which tube to enter and then the number of flies in each tube was counted. For this assay, vials of up to 25 newly eclosed males were collected and allowed to age for three to five days before testing. The assay was repeated up to six times. Wild type flies show positive phototaxis. The responses of all lov mutants are indistinguishable from the control line (df 5; χ2 = 5.17; Control = Canton S n = 100, lov91Y n = 170, lov38 n = 132, lov47 n = 82, lov66 n = 138, lov66/CyO n = 146).

(DOCX)

lov66 has a decreased response to sucrose. The proboscis extension response (PER) assay of Gordesky-Gold (Chemical Senses 33, 301–309, 2008) was used to investigate adult taste responses. Newly eclosed males were starved overnight in food vials with paper tissue moistened with water. Flies were then mounted on toothpicks with Tissue Tack and allowed to recover for three hours. Prior to testing, flies were satiated with water to ensure that tastant, and not water, responses, were assayed. Attractive (1% or 4% sucrose) or repellent (4% caffeine +4% sucrose) tastants were touched to the front legs and the proboscis response noted. Flies were tested three times, and given water between testings. A score of one (“tasting”) was given if a fly extended its proboscis all three times. Two additional trials were performed for flies with mixed responses in the first three trials. After five trials, any fly that extended its proboscis three or more times was scored as “tasting”. Approximately 50 flies from each line were tested. A chi square test was used to determine significance relative to the control, Ore R flies. The reduced response of lov66 to sucrose and stronger response of lov91Y to sucrose+caffeine are statistically significant. (4% Sucrose: df 5; Ore R n = 50, lov91Y n = 50, lov38 n = 50, lov47 n = 50, lov66 n = 47 (χ2 = 56.7), lov66/CyO n = 44 (χ2 = 56.7); 1% Sucrose: df 5; Ore R n = 50, lov91Y n = 50, lov38 n = 50, lov47 n = 48, lov66 n = 47 (χ2 = 50.2), lov66/CyO n = 44 (χ2 = 50.2); 4% Sucrose and 4% Caffeine: df 5; Ore R n = 50, lov91Y n = 50 (χ2 = 13.5), lov38 n = 50, lov47 n = 50, lov66 n = 51, lov66/CyO n = 51).

(DOCX)

Olfactory responses to a repellent odorant for lov mutants. Newly eclosed males were collected, aged for four to six days, then placed in empty food vials in groups of five. A Q-tip pre-soaked with 100 µl of repellent odorant (1% or 0.1% benzaldehyde) was then placed in the vial so that the tip was in the middle of the vial. For one minute, the number of flies at the far end of the vial (opposite the plug) was counted every five seconds. The number of flies at the far end was averaged to give an Olfactory Response Index (ORI). The assay was repeated ten times for each genotype. An ORI above 3 (above the red line) means flies are repelled by the odorant. A one-way ANOVA was performed to determine if there were differences among the lines. A Dunnett’s Test was used to compare the results of the mutant lines to the control, Ore R. Error bars represent standard error. Responses of the lov mutants to 1% benzaldehyde are indistinguishable from the control, Ore R, response (1% benzaldehyde: p = 0.593, n = 50 for all genotypes). The slightly stronger responses of lov91Y, lov38, lov66 and lov66/CyO to 0.1% benzaldehyde as compared to the control are statistically significant. (0.1% benzaldehyde: p = 0.004; n = 50 for all genotypes). Assay modified from Anholt and Mackay, Behav. Genet. 31,17–27, 2001.

(DOCX)

Olfactory responses to a neutral odorant for lov mutants. Newly eclosed males were collected, aged four to six days and then placed in an empty food vials in groups of five. A Q-tip pre-soaked with 100 µl of neutral odorant (water) was then placed in the vial so that the tip was in the middle of the vial. For one minute, the number of flies at the far end of the vial (opposite the plug) was counted every five seconds. The number of flies at the far end was averaged to give an Olfactory Response Index (ORI). The assay was repeated at least ten times so that a minimum of 50 flies were tested. An ORI between 2 and 3 (between the green and red lines) means flies are neutral to the odorant. A one-way ANOVA was performed to determine if there were differences among the lines. A Dunnett’s Test was used to compare the results of the mutant lines to the control, Canton S. Error bars represent standard error. The slight attraction to water shown by the control and the slight repulsion to water shown by lov47 are statistically significant. (p≤0.001; Control = Canton S n = 125, lov91Y n = 50, lov38 n = 50, lov47 n = 100, lov66 n = 50, lov66/CyO n = 50). Assay modified from Anholt and Mackay, Behav. Genet. 31,17–27, 2001.

(DOCX)

lov66 decreased fertility is attributed to the females. Average total progeny number for the crosses shown above was determined as follows. Single male/single virgin female mating pairs were set up in vials and transferred on day 8 and then day 16 to new vials. On day 24 they were removed from the third vial and discarded. Adult offspring were then collected from each vial for eight days after eclosion of the first adult. A minimum of 10 mating pairs were scored for each line. Female lov66 mutants have significantly decreased fertility when compared to lov66 males in terms of producing viable progeny when mated to control flies. A one-way ANOVA was performed to determined to assess significance of differences between crosses. A Dunnett’s Test was performed with w1118 as the control. Error bars represent standard error. *** = p<0.001 relative to the w1118 control; M = males; F = females.

(DOCX)

lov66 affects Broad expression in the ovary. In stage 10 of oogenesis, two patches of somatic follicle cells on the dorsal surface of the oocyte compartment show elevated nuclear expression of Broad (Tzolovsky et al., Genetics 153,1371–1383, 1999). This enhanced Broad expression commits the affected cells to dorsal appendage formation. A. The Broad patches (arrowheads) on a stage 10 wild type Canton-S egg chamber. Broad staining of the nurse cell nuclei (n) and oocyte nucleus (o) is artifactual and was intermittently seen with the antibody used. B. A normal size stage 10 egg chamber from a lov66 mother. Although the overall pattern of Broad expression is similar to wild type, enhanced Broad expression at the position of the two presumptive patches of dorsal appendage cells is barely detectable. C. A short stage 10 egg chamber from a lov66 mother. Again, overall patterning of Broad expression is relatively normal but expression within the patches is highly aberrant. D. Semi-Q RT-PCR to probe for all broad transcripts within ovaries from one-day-old control (w1118) and lov66 homozygous females shows that Broad expression is depressed in lov66 ovaries. Methods. A-C. Ovaries from Canton-S or lov66 homozygous mothers were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with the Broad-core monoclonal antibody 25E9-D7 (1∶250 dilution) from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank and an Alexafluor-488 labelled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen,1∶500 dilution). The Broad-core antibody recognizes sequences common to all isoforms of Broad. D. Semi-Q RT-PCR on ovarian RNA was performed as described in Material and Methods of the main text. Primers termed Broad F1 (5′ TGCAGGATGTCAACTTCATGGACC 3′) and Broad R (5′TATCTGAGCCAGATGGCTGTGTGT 3′), which span an exon-exon junction within the shared protein coding sequences of all broad transcripts, were used to probe for all processed broad transcripts. Actin 57B primers (see main text Material and Methods) were used in parallel to provide an internal control.

(DOCX)

Sperm transfer and storage is not impaired in lov66 mutants. A third chromosome don juan-GFP construct (Santel et al. Mech. Dev. 64, 19–30, 1997), which generates GFP-expressing sperm, was used to monitor sperm storage in the seminal vesicles and spermathecae of mated females. Males and virgin females were aged for 3–6 days after eclosion and set up in matings of the genotypes indicated. The sperm storage organs of females were dissected out after confirmed mating and were examined for GFP fluorescing sperm. There is no significant difference in the ability of lov66 males to transfer sperm or lov66 females to store sperm, relative to the w1118 and lov66/CyO controls. χ2 = 1.04.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Rice undergraduates Darin Carabenciov, Erica Huley, Megan Land, Angela Lin, James Liu, Helen Tsao, Peter Ye and Kevin Yi and summer students Lauren Anderson, Meg Bevilacqua, Mengwei Ni, and Charles Tian for their help with the experiments described here. We are also grateful to two visiting summer interns, Wankun Li and Xinyu Hong, from China for their valuable contributions to these studies.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NASA grant NNX09AH43G to Kathleen M. Beckingham. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.