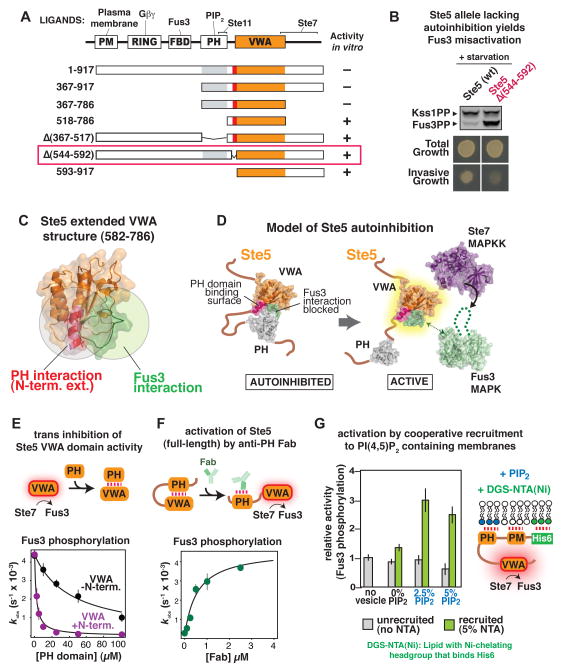

Fig. 3. Mechanism of Ste5 autoinhibition and activation by mating-specific input.

(A) Diagram of truncation mapping of Ste5 (red is residues 544–592). The minimal autoinhibited fragment (367–786) contains all elements necessary to assemble the three-tiered MAPK cascade (Fus3 is recruited to the VWA domain by Ste7 (16)). See fig. S9 for additional constructs.

(B) Effect of deletion of the N-terminal extension of the VWA domain in Ste5 (residues 544–592) to disrupt pathway insulation in vivo. Activation of Fus3 measured by protein immunoblotting, and invasive growth assayed on solid agar plates (assays conducted as in fig. 2C, see fig. S6).

(C) Crystal structure of Ste5582–786 (see Table S4 for crystallographic statistics). The N-terminal extension (582–592) is shown in pink, with surface residues necessary for trans inhibition by the PH domain (Fig. S10) shown as sticks in red. The Fus3-coactivating loop of Ste5 (743–756) is shown in green. The spatial proximity of the PH-domain interface and the site of Fus3 coactivation is illustrated by overlapping circles.

(D) Model for Ste5 autoinhibition inferred from truncation mapping data and Ste5582–786 crystal structure.

(E) Titration of the VWA domain with the PH domain results in inhibition of the Fus3 coactivator activity (kobs) of the VWA construct bearing the N-terminal extension (582–786, shown in pink), or lacking the N-terminal extension (593–786, shown in black). Error bars are standard deviations.

(F) Relief of autoinhibition in full-length Ste5 by a Fab antibody (SR13) that can bind the PH domain. Error bars are standard deviations.

(G) Recruitment of Ste5 to membranes with PIP2 stimulates coactivation of Fus3. A minimal, autoinhibited Ste5 fragment bearing a hexahistidine tag can be recruited to small unilamellar vesicles of varying lipid compositions by the DGS-NTA(Ni) lipid (see fig. S13 for exact details of the Ste5 construct used here). Error bars are standard deviations.