Abstract

Background

Effective communication is essential to safe and efficient patient care. Additionally, many health information technology (HIT) developments, innovations, and standards aim to implement processes to improve data quality and integrity of electronic health records (EHR) for the purpose of clinical information exchange and communication.

Objective

We aimed to understand the current patterns and perceptions of communication of common goals in the ICU using the distributed cognition and clinical communication space theoretical frameworks.

Methods

We conducted a focus group and 5 interviews with ICU clinicians and observed 59.5 hours of interdisciplinary ICU morning rounds.

Results

Clinicians used an EHR system, which included electronic documentation and computerized provider order entry (CPOE), and paper artifacts for documentation; yet, preferred the verbal communication space as a method of information exchange because they perceived that the documentation was often not updated or efficient for information retrieval. These perceptions that the EHR is a “shift behind” may lead to a further reliance on verbal information exchange, which is a valuable clinical communication activity, yet, is subject to information loss.

Conclusions

Electronic documentation tools that, in real time, capture information that is currently verbally communicated may increase the effectiveness of communication.

Keywords: ICU, communication, interdisciplinary, electronic health record

1. Background

Evidence linking ineffective communication in the inpatient setting to negative outcomes such as increased length of stay, increased patient harm and increased resource utilization heightens the need to understand patterns and perceptions of clinical information exchange [1–5]. Effective communication in the intensive care unit (ICU) is critical due to complex technologies, therapeutic interventions and high patient acuity [5]. Adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) is higher in high-technology institutions, such as those with certain types of ICU care, and will likely increase due to Meaningful Use [6]. In the United States, the Joint Commission has identified communication failures as the leading cause of sentinel events and listed ineffective shift report as a contributing factor [7].

Stein-Parbury and Liaschenko found that during stressful situations collaboration breaks down and professional boundaries are accentuated regarding who owns what kinds of knowledge and who is responsible for specific kinds of work [8]. The ICU is a stressful environment in which goals of patient care are dependent on many disciplines who must simultaneously work both autonomously and collaboratively [9]. Shift work in the ICU, specifically the frequent hand-off of patient care responsibilities to a different clinician, is known to increase the demand for effective communication such as the communication of shared plans and goals [10, 11]. Additionally, division of labor (i.e., distribution of activities and responsibilities), which is utilized by clinicians to increase system efficiency and overall functioning, is dependent on information exchange of common goals [9].

1.1 Theoretical Frameworks

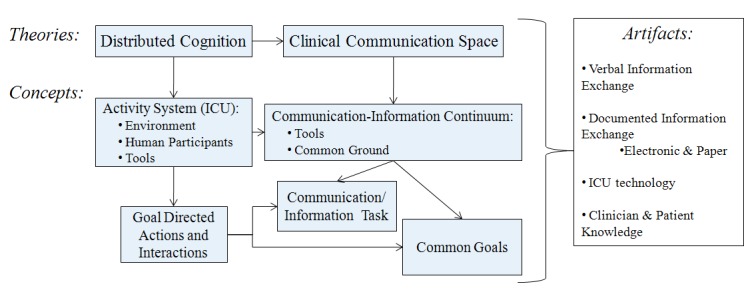

The theoretical frameworks of distributed cognition and Coiera’s clinical communication space facilitate understanding of clinician patterns and perceptions of the communication of common goals in the ICU (see ►Fig. 1) [12, 13]. In the theoretical framework of distributed cognition the unit of analysis is the activity system, which is composed of individuals and artifacts (e.g., technology). The theory posits that the pattern of information exchange can drastically modify the behavior of the activity system and that the behavior of the activity system should be described by the patterns of information flow [12]. As opposed to traditional cognitive frameworks that only analyze individual processes, distributed cognition integrates goal directed actions and interactions of individuals and artifacts, and information exchange within an activity system [12]. Distributed cognition, which has been applied to numerous contexts including aviation, education, psychology and health care, suggests that verbal descriptions often fail because the descriptions are poorly structured and, unlike documentation, the information will not endure over time [12, 14–16]. Therefore, distributed cognition supports the development of redundant storage and processing of information, enduring resources and the opportunity for checking and cross-checking critical information and the verification of decisions or common goals [14].

Fig. 1.

Integrated distributed cognition and clinical communication space theoretical frameworks

Communication between nurses and physicians is important in the ICU because these clinicians work closely together to coordinate ICU specific patient care, communicate frequently, and are the primary users of the EHR which includes electronic clinical documentation and a computer provider order entry (CPOE) system [17]. Coiera’s clinical communication space framework describes the communication and information exchange activities between clinicians within the activity system according to the amount of common ground (i.e., shared knowledge) that exists between the communicators [13]. Goal directed actions, such as patient care tasks, and interactions, such as communication tasks, can be explicitly modeled, and the appropriate communication or information tools can be anticipated using the clinical communication space framework. For example, Coiera reasons that humans favor information tools when we have high common ground and can formalize interactions ahead of time. In contrast, clinicians often prefer a communication space that enables face-to-face discussions because these interactions provide the needed opportunity to clarify clinical problems; furthermore, this preference may be a consequence of inadequate printed or electronic information [13]. Baggs describes ICU interdisciplinary collaboration as contingent upon the antecedent conditions of Being Available and Being Receptive which facilitate the core process of Working Together to achieve the outcomes of Improved Patient Care, Feeling Better on the Job, and Controlling Costs [18]. The key focus of this study is Working Together which we have previously described as an extension of the Baggs coding framework and that includes the Coordination and Sharing of patient care information in a Patient Focused, Team environment [19].

2. Objectives

The aims of this study were:

-

1.

To describe the ICU activity system in the context of interdisciplinary communication of common goals; and

-

2.

To describe nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of interdisciplinary communication of common goals in the ICU.

3. Methods

This study took place in the Neurovascular ICU (NICU) at a large urban academic medical center. The NICU is an 18 bed unit that specializes in intensive care for patients with neurovascular injuries; patients are transferred to a separate neurology floor from the NICU once they are stable and no longer require intensive care. The hospital’s vendor-based EHR system (Eclipsys Sunrise, Eclipsys Corp., Atlanta, GA) had been deployed since 2004 and supported electronic documentation of structured, semi-structured, and free text data for nurses, physicians, and respiratory therapists in the NICU. Free text data entry in the EHR included any type of unstructured clinical note such as, physician progress notes, comments entered into flowsheets, and end-of-shift nursing notes. A large portion of the EHR structured documentation consisted of the nurses’ and respiratory therapists’ flowsheets for assessments, interventions, and goals and the physician’s computer provider order entry.

3.1 Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected using ethnographic observation techniques, focus groups and interviews. The focus group and interviews were conducted at a convenient time and place for the ICU clinicians. During the focus groups and interviews a standard set of questions and prompts were used that focused on interdisciplinary communication of common goals in the context of EHR use. All of the participants were compensated with a $10 cash voucher for their time. The focus group and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a paid transcriptionist. The transcripts were verified against the audio-recordings by the lead researcher (SC) for accuracy. The field notes and interview transcripts were analyzed by the researchers for themes related to information exchange of common goals for patient care. ATLAS.ti™ (GmbH Berlin, Version 5.5.9) software was used.

We observed all clinicians who participated in interdisciplinary NICU morning rounds. During the observations the investigator (SC) observed and recorded handwritten field notes of the interactions of the entire NICU team (i.e., activity system) as defined by the distributed cognition and the clinical communication space theoretical frameworks. These interactions included conversations as well as clinicians’ use of documentation artifacts, such as electronic documentation in the EHR system and paper-based documentation. Data collection continued until data saturation (i.e., no new themes were identified) was achieved and the observational, interviews, and focus group data were triangulated for consistent themes.

3.2 Data Analysis

This descriptive study used the theoretical frameworks of distributed cognition and Coiera’s clinical communication space and categories of ICU interdisciplinary collaboration described by Baggs et al. [18] to identify and describe characteristics of information exchange related to common goals in the ICU environment. We analyzed the triangulated data using distributed cognition to describe the activity system and the goal directed actions and interactions within the activity system. The clinical communication space and Baggs’ ICU interdisciplinary collaboration coding [18] were used to describe the communication and information exchange activities within the activity system. Baggs’ coding framework was extended where needed. The results are presented as:

-

1.

The distributed cognition activity system description, and

-

2.

The clinical communication space information exchange description.

4. Results

Clinicians were observed during NICU interdisciplinary morning rounds for a total of 16 days during the fall 2008 and spring 2009 which resulted in fifty-nine and one-half hours of direct observation. A total of 31 nurses, 9 respiratory therapists, 10 residents, and 3 attendings were observed. Each observation of NICU rounds lasted between three hours and four and a half hours. We also conducted one focus group that consisted of eight NICU nurses, one interview with an ICU staff nurse, and four interviews with ICU residents.

4.1 Distributed Cognition Activity System

Within the NICU’s activity system, the individuals who were observed included the following types of clinicians:

-

1.

Physicians (e.g., attendings, fellows, residents, and medical students);

-

2.

Nurses (e.g., charge nurse, staff nurses, and nursing students);

-

3.

Pharmacists; and

-

4.

Respiratory therapists.

If possible, a clinician would care for the same patient on subsequent days, but due to scheduling and patient acuity this was not always possible. ►Table 1 describes the planned and unplanned information exchange activities and the artifacts used within the ICU activity system.

Table 1.

ICU Planned and unplanned information exchange activities

| Nurses’ report | Residents’ sign-out | ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds | Updates | Neurosurgery rounds | Charge nurse rounds | Disposition rounds | Medical rounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication Type | Planned, verbal | Planned, verbal | Planned, verbal | Unplanned, verbal | Planned, verbal | Planned, documented | Planned, verbal | Planned, verbal |

| Participants | Night-shift nurse & day-shift nurse | Night-shift resident & day-shift resident | Neurology attending, fellow & residents; staff nurse; pharmacist; medical & nursing students (respiratory therapist intermittently) | Any clinician | Neurosurgery attending & resident, neurology attending & fellow, charge nurse | Charge nurse and, individually, the nurse for each patient | Charge nurse, social worker, & neurology fellow | Neurology attending, fellow, & residents |

| Frequency/Timing | 7 am & 7 pm | 7 am & about 6 pm | 7:30 am until 10:30–12 pm | Anytime needed | Between 8–11 am | About 6 am & about 6 pm | Between 9–11 am | About 5 pm |

| Approximate | 15–30 minutes/one patient | 15–30 minutes/all of resident’s patients | 3–4.5 hours/all ICU patients | Typically 30 seconds to 15 minutes/one patient | 10–15 minutes/all ICU patients | Less than 1 minute/one patient | 15–30 minutes/all ICU patients | 30 minutes/all ICU patients |

| Artifacts | Personal notes* | Personal notes* | EHR; personal notes* | EHR; pager; personal notes* | Personal notes* | Personal notes* & charge nurse paper note | Personal notes* & charge nurse paper note | Personal notes* |

EHR= electronic health record, *Personal notes = paper-based to-do list, paper-based vital-signs flow-sheet and printed information from EHR (NOTE: there was not a ‘typical’ type of ‘personal notes’ used by any of the clinicians during these information exchange activities)

Within the NICU, there was a computer in each patient’s room; additionally, there was a desktop computer outside of every other patient room and a separate workstation used for rounds that had two desktop computers and a computer on wheels. The paper and computer-based artifacts used by the clinicians as information resources in the NICU were used to provide and capture information during and after ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds. During ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds, the artifacts that provided information to the clinicians were:

-

1.

Computer terminals used by the attending, two residents and a pharmacist to provide access to the hospital’s EHR system; and

-

2.

Personal notes.

These personal paper-based notes were carried by clinicians and included information written down during hand-off and throughout their shift. Personal notes consisted of the clinicians’ to-do lists and the nurses’ paper-based vital signs flow-sheet, as well as printed information from the EHR such as the medical administration record (MAR) and the attending’s ICU note or the resident’s sign-out note. During rounds, two day shift residents sat at computer terminals and, based on the discussion, retrieved laboratory values, clinician notes, vital signs, and radiology results such as x-rays from the EHR.

Additionally, the overnight resident, who had worked the previous night, presented information about the patient and referred to information that he or she printed from the EHR system as well as personal notes such as to-do lists. The patients themselves also served as an information resource during the moments that the team was in the patient’s room during ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds. For example, during a given patient’s bedside assessment the team also referred to data from the various therapeutic technologies in the room such as ventilator settings, intravenous medications, intravenous pumps rates, cardiac monitoring, and intracranial pressure monitoring data.

The artifacts for documentation that were used by clinicians to record the information that was discussed during rounds included paper documentation and the electronic CPOE system. The attending physician documented what was discussed by all of the clinicians who were present at rounds on the “Attending ICU note” in the EHR system. Additionally, each one of the other clinicians were observed to hand write brief notes on their own personal papers at varying time points. The residents, using the computer terminal, continuously entered discussed orders into the CPOE system during rounds. Besides the “Attending ICU note” which was completed at rounds, notes were completed by each clinician before leaving the unit at the end of his or her shift.

In addition to the artifacts that were used during rounds, the EHR system included an interdisciplinary plan of care flow sheet. Nurses, respiratory therapists and nutritionists used this structured electronic flow sheet to document care. Nurses were required to complete the structured vital sign and neurological flowsheets every hour. However, this flow sheet was not talked about or looked at during ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds. The only documents that were looked at during rounds were the “Vital Signs” and the “Intake and Output” flow sheets in the EHR system as well as the paper-based vital signs flow sheet used by nurses. A paper-based nursing care plan was available but was not used; the nurses stated that it could be useful, but that they did not want to have to fill out any further documentation or duplicate information that they already documented in the EHR system. There was no use of a multidisciplinary round sheet during daily rounds.

Despite documenting vital signs, medications, and fluids in the EHR system, the nurses also documented the patient’s vital signs and intravenous medications and fluids on the paper-based vital signs flow sheet that they carried around with them. The charge nurse also used a paper-based sheet that was written on and updated by each nurse during nursing rounds. This sheet contained information about each patient’s diagnosis, any abnormal vital signs, intravenous lines, and plans for imaging tests (e.g., computed axial tomography, also known as a CAT scan) or surgery. The charge nurse’s information sheet also contained information about interventions such as the use of a cooling blanket, if Tylenol was given for a fever (a fever is a concern for neurological patients due to a link to poorer outcomes [20]), and if intravenous medications were used to control the patient’s blood pressure. There was no formal structure (e.g., SBAR) used by the clinicians during handoff. During the end-of-shift handoff, the residents used their sign-out note that was printed from the EHR with handwritten personal “to-do” notes on it and the nurses used their paper-based flowsheets and personal notes.

4.2 Clinical Communication Space

Clinician perceptions and patterns of interdisciplinary communication and information exchange activities were coded according to Baggs’ ICU Interdisciplinary Collaboration coding framework. We found that clinicians preferred verbal discussions as a method of Coordinating and Sharing information that is Patient Focused within a Team environment. Therefore, to explicitly capture verbal discussions as a clinical communication space concept of communication and information tasks we added the codes Verbal and Documentation Information Exchange to the ICU collaboration framework (►Table 2). All of the ICU Interdisciplinary Collaboration categories had positive and negative aspects; therefore, they are all represented by positive and negative clinician quotations.

Table 2.

ICU Interdisciplinary collaboration coding framework and Ssupporting quotations: core process of working together [18, 19]

| Team | (+) Resident: [During rounds] a resident can easily enter orders on the wrong patient or confuse orders because they are catching up on previous patients…there are some good pharmacy checks and there are good nursing checks, [that] is the way…that orders are done correctly. |

| (-) Nurse: There are so many clinicians involved in patient care at a teaching hospital that it can be challenging for one to recall who he or she spoke to about an issue, information or a request. | |

| Patient focus | (+) Nurse: In a subspecialty unit like ours, there are certain standards that we all know and follow. |

| (-) Resident: It’s not that it’s not patient-focused, but it’s just everybody is very collegial a lot of times. I think there’s a lot of unspoken, like this is what we’re doing. We’re giving a little albumin; we’re waking them up. And sometimes it’s said, sometimes it’s just implied. | |

| Coordination | (+) Resident: For some tasks the resident has to do some things and the nurse will wait…and then like when the nurse is admitting the patient…after the resident can figure some stuff out. |

| (-) Nurse: Things are delayed for any patient, stable or unstable because of rounds…[the residents will say] “well, we’re going to put an order in for that, but we’re not putting it until after rounds are over.” | |

| Sharing | (+) Resident: [During rounds] the resident presents what he or she heard happen overnight and how the issues were dealt with. And the nurse will mention, “well this is what I got in my sign-out.” It is usually in agreement with minor variations of what the numbers are. |

| (-) Resident: Someone will say, “Oh, this patient is on Lasix,”…and another will say, “No, we stopped that days ago.” And it’s funny how you can’t agree on something as simple as a medication. | |

| Verbal Information Exchange1 | (+) Resident: It’s a lot faster and easier to ask ‘Please, just verbally, quickly tell me what’s going on.’ |

| (-) Nurse: It doesn’t all get written down [at rounds] and the night nurses don’t know, sometimes in the report it gets lost in transition…miscommunication or doesn’t get passed on, and you work twelve hours with one eye closed, basically not having all the information with you. | |

| (-) Resident: A third of the time, usually the event is communicated verbally and the issues or treatment and results are communicated verbally again, but nothing’s ever written down. | |

| Documentation Information Exchange1 | (+) Resident: The [beside chart] of the nurse’s notes…past medical history and pertinent… a log of what happened. If I know a specific event happened, and I’m trying to get more details, that’s where I may go. |

| (+) Nurse: Writing things down in succinct manner physically next to the patient is very helpful. Because [then] everyone’s very aware of it and people start saying, “Hey, did you see them?” “No, let’s call them again.” It’s very helpful in getting things done and communicating, because it’s written down, kind of almost set in stone once something’s written down. | |

| (-) Nurse: The computer system doesn’t even remotely match what’s going on with the patient. It’s ridiculous; there’ll be Cardizem hanging [intravenous medication] and no orders for it [in CPOE system]. |

1Category added; (+) positive aspect of category, (-) negative aspect of category

4.2.1 Verbal Information Exchange

Overall, verbal communication was the preferred method of information exchange in this ICU. The residents used the EHR system to retrieve vital signs, the patient’s fluid balance and to make sure that orders were entered; the residents verbally asked the nurse for other information related to the nursing assessments, interventions, evaluations and coordination of care for the patient. The residents stated that they place emphasis on entering new orders in the CPOE system, yet the nurses stated the importance of verbally communicating and discussing these orders to verify the EHR information in an effort to ensure the quality and safety of patient care. For example, the nurses stated that CPOE orders may only imply what the related patient goal was; therefore, if a goal related to an order was not previously discussed or documented the nurses’ verbal double check may be the only form of verification that the order was entered as intended. The nurses emphasized that part of sharing goals is making sure everyone knows the reason for why you are making a change. “Whether or not some documentation is updated is variable, but [we try] to always verbally communicated the updates to each other in shift report.”

Common goals for the patient were verbally shared by physicians and nurses during morning rounds; yet, the clinicians acknowledged that sometimes a goal was explicitly stated and sometimes it was just implied in a CPOE order or other documentation and without a verbal double check it may be missed, forgotten or not prioritized as intended. Nurses stated that if they were not present at rounds, due to conflicting patient care responsibilities at that time, they would piece together the plan and determine the patient’s goals from their own assessment, attending note, resident sign-out, nurse shift report, orders and unit standards “that we all know.” During the observations, the charge nurse and the fellow (i.e., a physician receiving specialty training) acted as liaisons between the medical and nursing teams. There was no formal team-based meeting after morning rounds to communicate changes in plans between nurses and physicians or to come to consensus about changes in patient goals. As one nurse stated, “sometimes nursing goals and medical goals conflict; however, due to the high amount of verbal communication on the unit they often overlap.” The residents and nurses agreed that “if goals are known they are used to guide the day.” Therefore, the clinicians expressed that it may be beneficial to provide unified general patient goals, specific tasks and major events of the day in a simple format that is readily accessible and contributed to by everyone.

4.2.2 Documentation Information Exchange

Clinicians emphasized aspects of documentation in the ICU that inhibited their workflow such as patient information contained in multiple disparate sections of the EHR, and information that was not updated to reflect current patient goals. Moreover, nurses commended that orders appear in the CPOE system that were not explicitly related to the nurses perceived understanding of the common goals for the patient. One resident described difficulty in keeping the medication list accurate: “Yes, because I find that it changes frequently, that list, whether it’s the drips versus the standing medications.”

However, the clinicians also described aspects of the computer-based documentation that enhanced clinical workflow. One resident stated that documenting a plan “can solidify it” to help to ensure that the plan will be carried out and its progress will be evaluated. Nurses commented that ‘if someone forgot to tell you the plan in report, it was wonderful if it was written in the computer.’

Our observations identified that the structured documentation in the EHR was typically supplemented by electronic free text notes written by nurses and electronic sign-out notes written by residents at or near the end of their shifts. These notes included information that may have been documented in a structured format in other parts of the EHR, but summarized the structured data and provided additional contextual information in order to “tell the story” of the patient and the patient care that was provided during that shift.

5. Discussion

Computerized systems may increase the effectiveness of communication within the nursing or medical discipline [10, 21]. However, the integrated distributed cognition and clinical communication space analysis demonstrated the perceived lack of effective and updated electronic documentation artifacts within the ICU activity system that was examined. Overall, we found that goal setting is an important but under-recognized activity and the design of EHRs that facilitate the capturing of implicit goals and rationales for orders in CPOE systems may increase provider satisfaction and improve safety.

Limited use of electronic documentation restricts the ability of clinicians to establish common ground through the EHR regarding their goal directed actions and interactions, communication and information tasks, and common goals of patient care. Our analysis suggests that when the EHR does not facilitate the establishment of common ground clinicians prefer verbal information exchange. These findings are consistent with Coiera’s argument that the communication space is the preferred interaction mode for clinicians [13].

Based on the clinicians’ statements during the focus group and interviews, information contained in the EHR is often perceived to be a shift behind (e.g., night shift or day shift) and includes only the clinical care that has already been provided to the patient. Therefore, the current structure and content of the documentation tools in the NICU may not be sufficient to capture the information exchange of common goals that occurs during and in between ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds. The perceived lack of updated documentation may increase clinicians’ reliance on verbal communication. For instance, if the clinicians perceive that other clinicians are not updating the electronic documentation frequently they may wonder if frequently updating the electronic documentation is an efficient use of their time during their shift in the fast paced and complex ICU environment where they are caring for critically ill patients.

These perceptions likely influence clinicians’ behavior to electronically document patient information at the end of their shift or to omit information that had been verbally exchanged from the electronic documentation. Kim et al., also found that the restrictions imposed by the EHR developers caused nurses to omit many information layers and data categories that would have represented greater contextual information that was useful for clinical care as well as for data reuse for administrative and research purposes [22].

Clinicians’ continued reliance on personal paper-based notes suggests that the EHR may facilitate establishing common ground amongst the clinicians. One of the intended useful roles of an EHR at the point of care is to provide clinicians with access to shared information regardless of constraints such as their location or the time of the day. The sharing of paper based documentation is limited by constraints such as the location of the documentation or the shift worked by the clinician that is in possession of the paper documentation.

Of note, the clinicians who were interviewed appreciated the potential benefits of electronic documentation such as increasing common ground regarding the patient’s plan of care, preventing information loss, and increasing the opportunity for information retrieval. However, the continued use of personal paper-based documentation by clinicians and their preference for verbal communication, despite their acknowledgments of the potential benefits of electronic documentation, are evidence that clinicians are ignoring aspects of the EHR tools that do not fit into their clinical workflow.

Despite the clinicians’ perceived limitations of the EHR to support ICU communication and information exchange activities, the clinicians continued to use the EHR; however, they supplemented the system by implementing verbal information exchange conventions. These verbal conventions were used to double check the EHR information in an effort to ensure the quality and safety of patient care. In a previous study we found that nurses perform these double checks by determining the physician’s rationale for an order as a method to assess the safety and appropriateness of the order [23].

These finding about the clinicians’ use of verbal double checks relate to Hazlehurst and colleagues conclusion that multiple representations, or redundancy, of information in the ICU increases robustness of the system and ensured correct functioning [24]. Including contextual clinical information linked to CPOE orders or nursing actions, such as the rationale or an explicit patient goal, may provide the multiple representations that may be sufficient as a double check.

Moreover, the clinicians’ free text documentation in the EHR provided contextual information and summarization of the interpretation and meaning of the structured data points in various parts of the EHR. Clinicians’ discussions may inform the “story of the patient” that is told in the free-text documentation; additionally, a clinician may “tell the story” of the patient in free-text documentation because once his or her shift is over there likely will be no further opportunities to discuss and convey summarized and contextual information about the patient with other clinicians who may care for the patient.

Given that clinicians document this rich contextualized information, but clinicians perceive EHR information retrieval as inefficient, the development of communication tools within the EHR may facilitate the efficient exchange of pertinent information about the “patient’s story” that clinicians choose to document.

Moreover, communication tools within the EHR may provide a medium for clinicians to verify EHR information with each other and document that verification [25]. We know that information that is routinely exchanged is ripe for tools that automate that exchange [13]; therefore the information that is routinely verbally discussed during rounds or documented in free-text notes may be appropriately exchanged using EHR tools that increase the efficiency of information exchange. Specifically, information exchanges that summarize and update patient data may be ripe for an EHR information tool and an EHR communication tool, such as online messaging, may be appropriate for information exchanges that contextualize patient data to “tell the patient’s story” [13, 25].

The limitations of this study are that the observations were conducted on one NICU and that all of the clinicians that were interviewed or participated in the focus group were from one hospital. Therefore, some of the findings may not be transferable to different ICUs, different types of patient care settings, or other hospitals. Additionally, we did not conduct any observations during the night shift in the ICU. However, the data saturation and triangulation of the observational, focus group and interview data increase confidence in the discussed themes and conclusions drawn from this study.

6. Conclusion

The large amount of information that is verbally exchanged amongst clinicians is evidence that clinicians have not harnessed the EHR tools available for their maximum use of information exchange and confirms Coiera’s theory of the clinical communication space [13]. According to the clinicians observed and interviewed, EHR documentation is a shift behind and information retrieval is not efficient, leading to a further reliance on verbal information exchange. Moreover, verbal information exchange is subject to information loss.

Our data indicate that the current documentation tools in the NICU may not be sufficient to capture the interdisciplinary communication of common goals that occurs during, and in between, ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds. The development of EHR information and communication tools should target verbal information exchange and free text documentation in the ICU. Therefore, future research should aim to further understand and meet the need for EHR information and communication tools to support verbal information exchange in the ICU in real time.

Clinical Relevance

A large amount of clinical information is verbally exchanged within the ICU which may lead to information loss and impact patient safety. Reliance on verbal information exchange impacts perceptions that the EHR is a “shift behind” and inefficient to support clinical care information needs. EHR systems should include tools that support the exchange of information that is routinely verbally exchanged in the ICU.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were responsible for the study design. SC, supervised by LC, was responsible for the data collection and data analysis. SC was responsible for the drafting of the article, and all authors performed critical revisions of the article for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in the research.

Human Subject Research

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained for all activities and informed consent was obtained from participants.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute for Nursing Research T32NR007969 and by Wireless Informatics for Safe and Evidence-based APN Care (D11 HP07346). Dr. Collins is supported by T15 LM 007079.

References

- 1.Fagin CM. Collaboration between nurses and physicians: no longer a choice. Acad Med 1992; 67: 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larson E. The impact of physician-nurse interaction on patient care. Holist Nurs Pract 1999; 13: 38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sexton JB, Thomas EJ, Helmreich RL. Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross sectional surveys. BMJ 2000; 320: 745–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zwarenstein M, Reeves S. Working together but apart: barriers and routes to nurse – physician collaboration Jt Comm J Qual Improv 2002; 28: 242– 7, 209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pronovost P, Wu A, Sexton J. Acute decompensation after removing a central line: practical approaches to increasing safety in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140: 1025–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Electronic Health Record Incentive Program. In Baltimore, MD; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sentinel event alert. Available athttp://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert/

- 8.Stein-Parbury J, Liaschenko J. Understanding collaboration between nurses and physicians as knowledge at work. Am J Crit Care 2007; 16: 470–477; quiz 478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel VL, Zhang J, Yoskowitz NA, Green R, Sayan OR. Translational cognition for decision support in critical care environments: a review. J Biomed Inform 2008; 41: 413–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strople B, Ottani P. Can technology improve intershift report? What the research reveals. J Prof Nurs 2006; 22: 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora V, Johnson J, Lovinger D, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer DO. Communication failures in patient sign-out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care 2005; 14: 401–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutchins E. Cognition in the Wild. Cambridge MA: MIT Press; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2000; 7: 277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchins E. How a cockpit remembers its speeds. Cognitive Science 1995; 19: 265–288 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown A. Distributed expertise in the classroom. : Salomon G, editor. Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations. New York: Cambridge UP; 1993, p. 188–228 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hazlehurst B, Gorman PN, McMullen CK. Distributed cognition: An alternative model of cognition for medical informatics. Int J Med Inform 2008; 77: 226–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munir SK, Kay S. Organisational culture matters for system integration in health care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2003: 484–488 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH. Nurses’ and Resident Physicians’ Perceptions of the Process of Collaboration in an MICU. Research in Nursing and Health 1997; 20: 71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins S, Currie L. Interdisciplinary Collaboration in the ICU. Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on Nursing Informatics. 2009; 146: 362–366 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badjatia N. Fever control in the neuro-ICU: why, who, and when? Curr Opin Crit Care 2009; 15: 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Eaton EG, Horvath KD, Lober WB, Rossini AJ, Pellegrini CA. A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign-out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 200: 538–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim H, Harris MR, Savova GK, Chute CG. The first step toward data reuse: disambiguating concept representation of the locally developed ICU nursing flowsheets. Comput Inform Nurs 2008; 26: 282–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins SA, Currie LM, Bakken S, Cimino JJ. Information needs, Infobutton Manager use, and satisfaction by clinician type: a case study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009; 16: 140–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hazlehurst B, McMullen C, Gorman P, Sittig D. How the ICU follows orders: care delivery as a complex activity system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2003: 284–288 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins S, Bakken S, Vawdrey D, Coiera E, Currie L. Model development for EHR interdisciplinary information exchange of ICU common goals. Int J Med Inform 2010[epub ahead of print] available online 25. October2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]