Abstract

Periodontitis is a group of inflammatory diseases affecting the supporting tissues of the tooth (periodontium). The periodontium consists of four tissues : gingiva, alveolar bone and periodontal ligaments. Tobbaco use is one of the modifiable risk factors and has enormous influance on the development, progres and tretmen results of periodontal disease. The relationship between smoking and periodontal health was investigated as early as the miiddle of last century. Smoking is an independent risk factor for the initiation, extent and severity of periodontal disease. Additionally, smoking can lower the chances for successful tretment. Tretmans in patients with periodontal disease must be focused on understanding the relationship between genetic and environmental factors. Only with individual approach we can identify our pacients risks and achieve better results.

Key words: smoking, periodontal disease.

1. INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a group of inflammatory diseases affecting the supporting tissues of the tooth (periodontium). The periodontium consists of four tissues : gingiva, alveolar bone and periodontal ligaments.

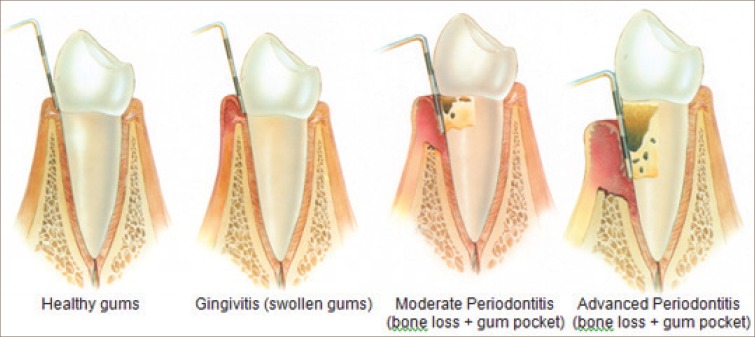

The periodontal diseases are highly prevalent and can affect up to 90% of the world wide population. Gingivitis, the mildest form of periodontal disease, is caused by the bacterial biofilm (dental plaque) that accumulates on teeth adjacent to the gingiva (gums).

The simtoms are usualy red, swollen gums who can bleed easily. However, gingivitis does not affect the underlying supporting structures of the teeth and is reversible. When gingivitis is not treated, it can advanece to periodontitis. Periodontitis results in loss of connective tissue and bone support and is a major cause of tooth loss in adults (1). In addition to pathogenic microorganisms in the biofilm, genetic and environmental factors has enormouse influence on development periodontal disease.Tobbaco use is one of the modifiable risk factors and has enormous influance on the development, progres and tretmen results of periodontal disease.

The American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) has classified periodontitis into aggressive periodontitis (AgP), chronic periodontitis (CP) and periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic diseases (2). Both AgP and CP have a multi-factorial etiology with dental plaque as the initiating factor (3). However the initiation and progression of periodontitis are influenced by other factors including tobbaco use.

2. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SMOKING AND PERIODONTAL DISEASE

One-third of the world’s adult population are smokers (57% of these are men, 43% are women) . It is predicted that in 20 years this yearly death rate from tobacco use will be more than 10 million people. Smoking in developing countries is rising by more than 3% a year (4). We can assume periodontal diseasees will also rise.

The relationship between smoking and periodontal health was investigated as early as the miiddle of last century. Smoking is an independent risk factor for the initiation, extent and severity of periodontal disease. Additionally, smoking can lower the chances for successful tretment. (Figure 1,2,3).

Figure 1.

Generalized advanced chronic periodontitis in smooker.

Figure 2.

Generalized advanced chronic periodontitis in smooker.

Figure 3.

Progression of periodontal disease :http://www.stcatherinesdentalpractice.co.uk/dental-treatments-in-grantham/periodontal-treatment-in-grantham.html.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal data provide strong support for the statement that the risk of developing periodontal disease as measured by clinical attachment loss and alveolar bone loss increases with increased smoking. Studies find that former smokers (clinically defined as two or more years since quitting smoking) experience less attachment loss than current smokers but more than neversmokers. Furthermore, the likelihood of developing increasing periodontal disease exhibits dose dependency (5).

For many years sciences did not know how smoking affect periodont and why people with chronical periodontitis have reduced clinical inflammation.Today we know that tobacco smoke induces alterations to the 3-OH fatty acids present in lipid A in a manner consistent with a microflora of reduced inflammatory potential.

In investigation smookers had significant reductions in the 3-OH fatty acids associated with the consensus (high potency) enteric LPS structure were noted in smokers compared with non-smokers with chronic periodontitis. Thus, smoking is associated with specific structural alterations to the lipid-A-derived 3-OH fatty acid profile in saliva that are consistent with an oral microflora of reduced inflammatory potential.(6).

These findings provide much-needed mechanistic insight into the established clinical conundrum of increased infection with periodontal pathogens but reduced clinical inflammation in smokers.

Bagaitkar and asos. established that exposure of P. gingivalis to tobacco smoke extract increased the expression of the major fimbrial antigen (FimA), but not the minor fimbrial antigen (Mfa1). That means that exposure did not induce P. gingivalis auto-aggregation but did promote dual species biofilm formation, monitored by microcolony numbers and depth. Interestingly, P. gingivalis biofilms grown in the presence of tobacco smoke exhibited a lower pro-inflammatory capacity (TNF-α, IL-6) than control biofilms. The underlying mechanisms are unknown, more likely tobacco smoke represents an environmental stress to which P. gingivalis adapts by altering the expression of several virulence factors–including major and minor fimbrial antigens (FimA and Mfa1, respectively) and capsule–concomitant with a reduced pro-inflammatory potential of intact P. gingivalis(7,8).

In vitro studies have shown altered gingival crevicular fluid inflammatory cytokine profiles (GCF) ,immune cell function and altered proteolylic regulation in smokers.

Smokers exhibited a decrease in several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and certain regulators of T-cells and NK-cells. This reflects the immunosuppressant effects of smoking which may contribute to an enhanced susceptibility to periodontitis (9).

Periodontal treatment tends to be less likely to be successful in smokers than in non-smokers. Studies evaluating the efficacy of periodontal disease control and specific periodontal procedures including regenerative procedures, soft tissue grafting procedures and implant procedures have consistently demonstrated a negative effect from smoking on success rates(10).

3. CONCLUSION

Smoking is well-established risk factor for periodontal disease. It changes the humen microflora , humen immune response that leads to destruction of the supporting tissues of the tooth. Difficult circumstance is a fact that simptoms in periodontal disease in smookers are increased so It can take years before the patient seeks help, then it is often too late.

Tretmans in patients with periodontal disease must be focused on understanding the relationship between genetic and environmental factors. Only with individual approach we can identify our pacients risks and achieve better results.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal disease and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Page RC, Offenbacher S, Schroeder HE, Seymour GJ, Kornman KS. Advances in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: summary of developments, clinical implications and future directions. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:216–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00199.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal disease. The Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809–1820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagaitkar J, Daep CA, Patel CK, Renaud DE, Demuth DR, Scott DA. Tobacco smoke augments Porphyromonas gingivalis–Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayman L, Steffen MJ, Stevens J. Smoking and periodontal disease: discrimination of antibody responses to pathogenic and commensal oral bacteria. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164(1):118–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buduneli N, Larsson L, Biyikoglu B, Renaud DE, Bagaitkar J, Scott DA. Fatty acid profiles in smokers with chronic periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2011;90(1):47–52. doi: 10.1177/0022034510380695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/releases/9702.php .

- 7.http://dentalstudynotes.pgpreparation.in/2007/12/periodontitis.html .

- 8.Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: findings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 2000;71(5):743–751. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tymkiw KD, Thunell DH, Johnson GK, Joly S, Burnell KK, Cavanaugh JE, Brogden KA, Guthmiller JM. Influence of smoking on gingival crevicular fluid cytokines in severe chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2011 Mar;38(3):219–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01684.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagaitkar J, Demuth DR, Daep CA, Renaud DE, Pierce DL, Scott DAP. Gingivalis fimbrial proteins which induce TLR2 hyposensitivity. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e9323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]