Abstract

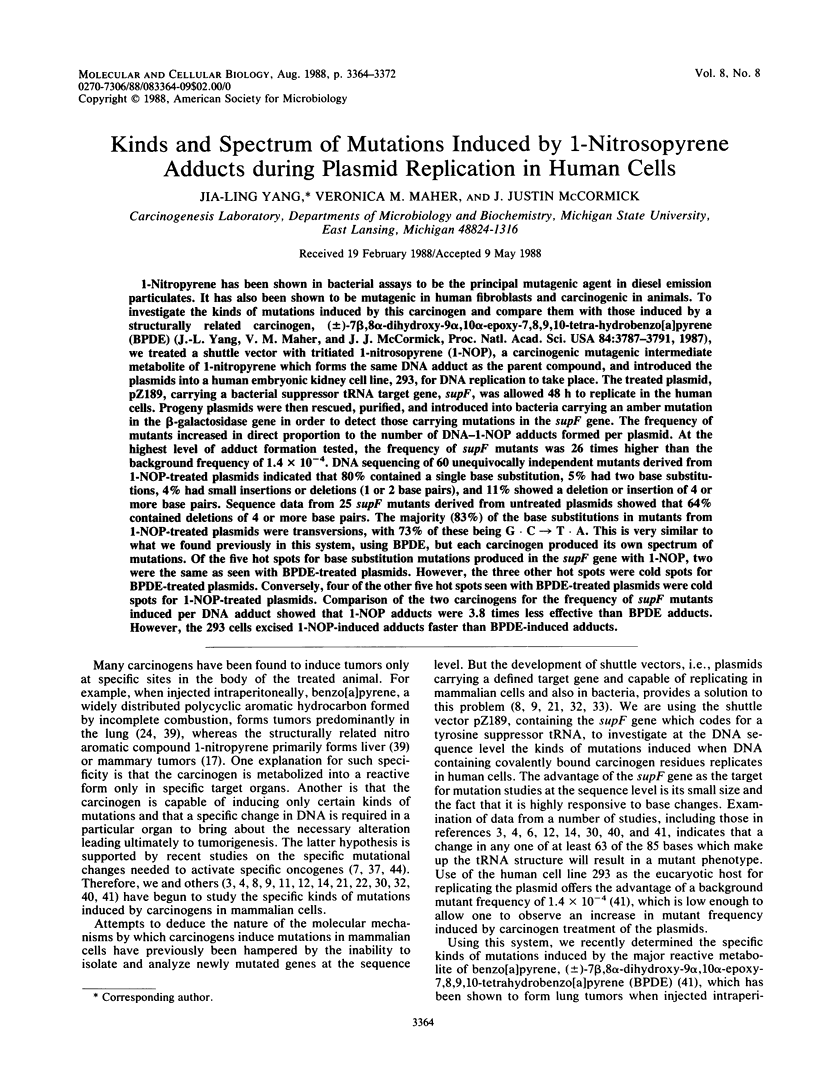

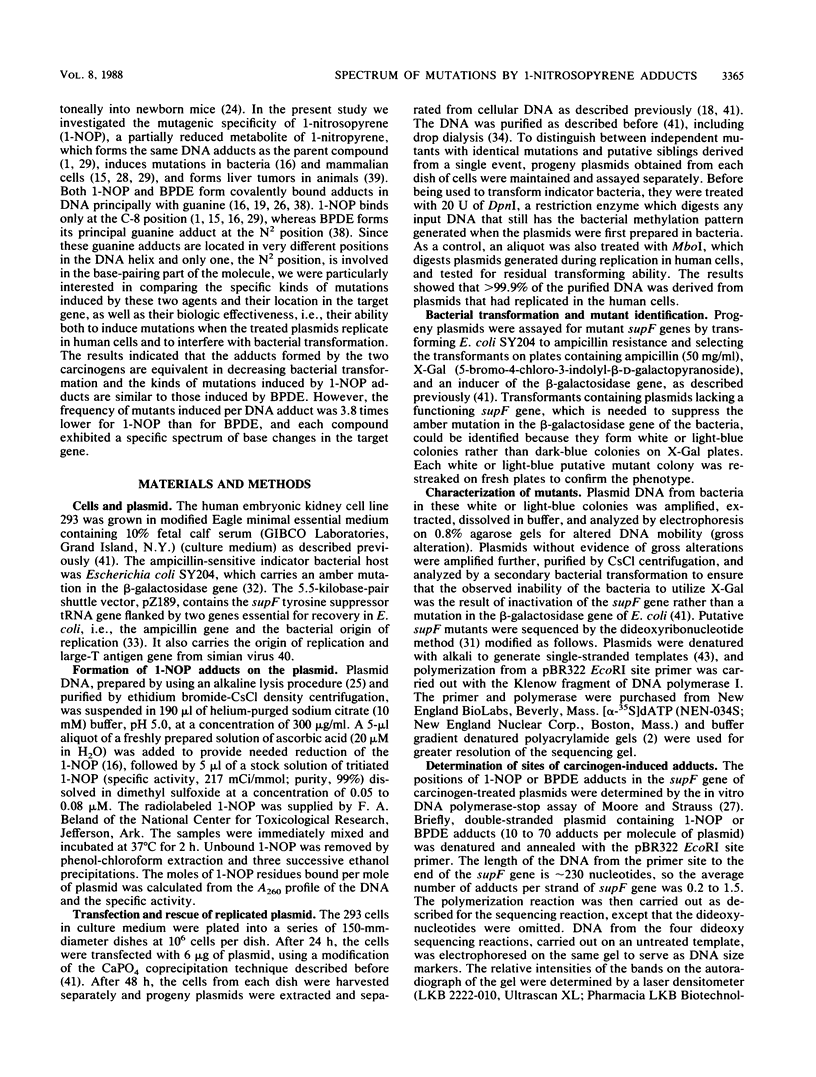

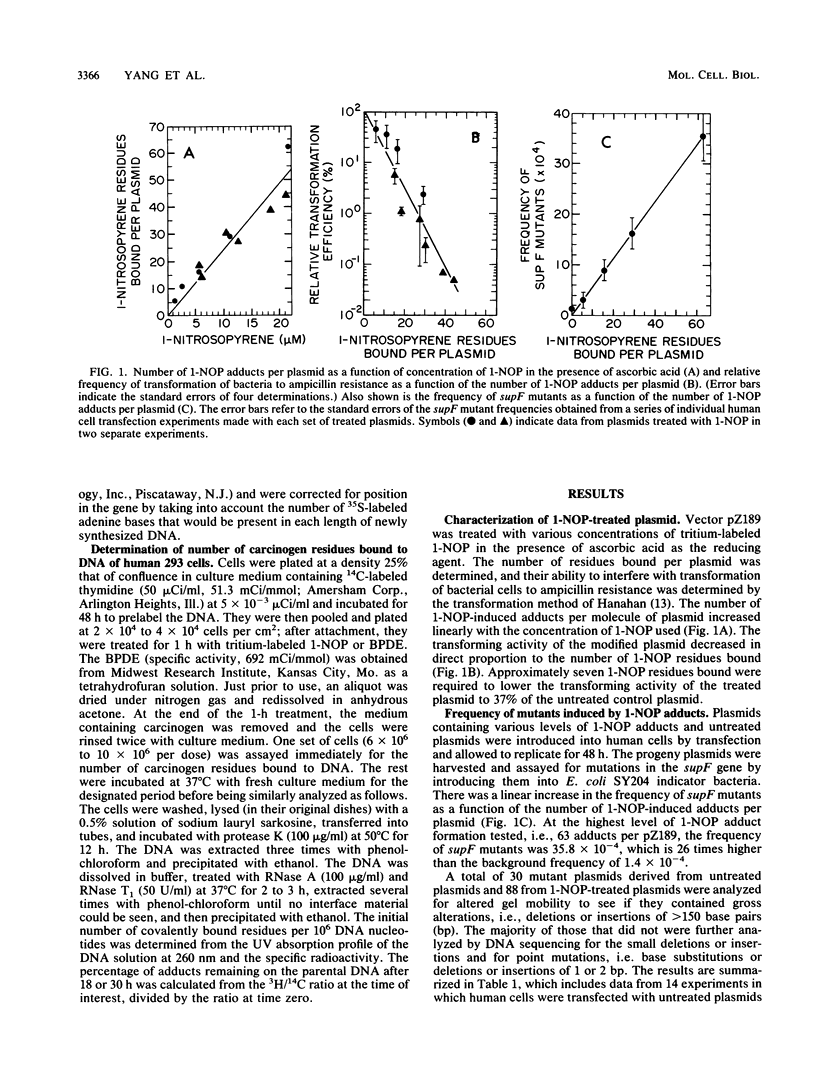

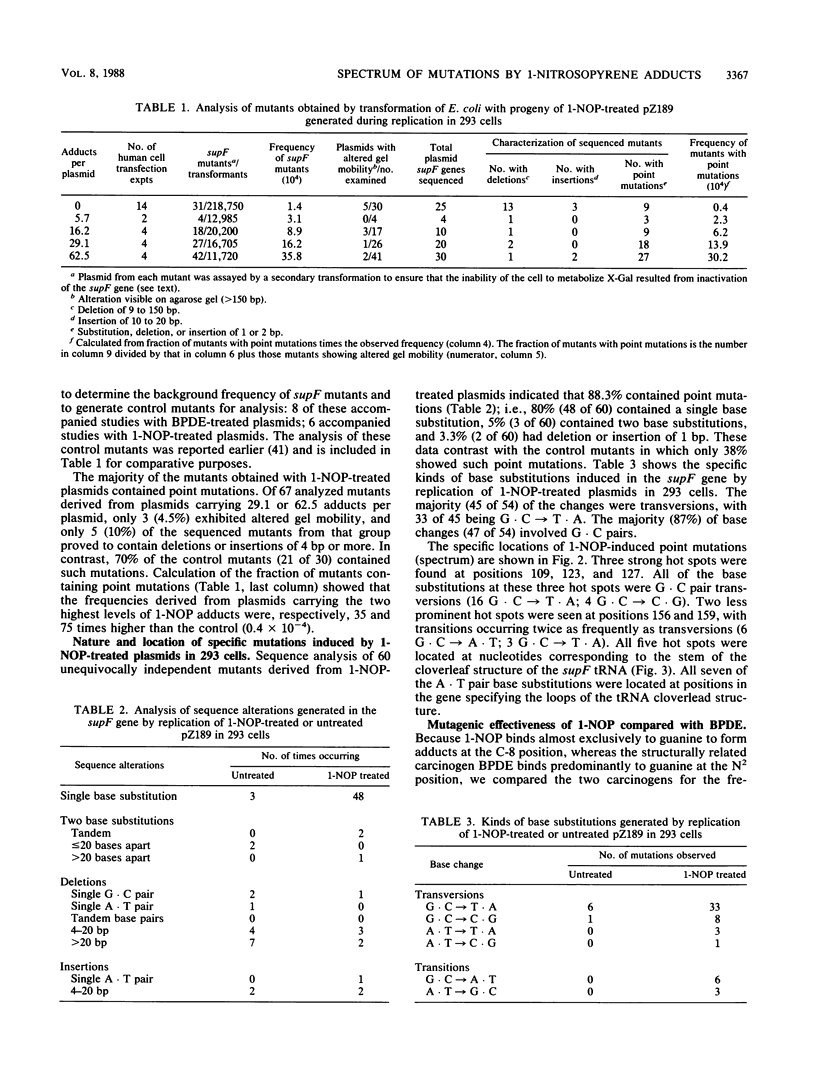

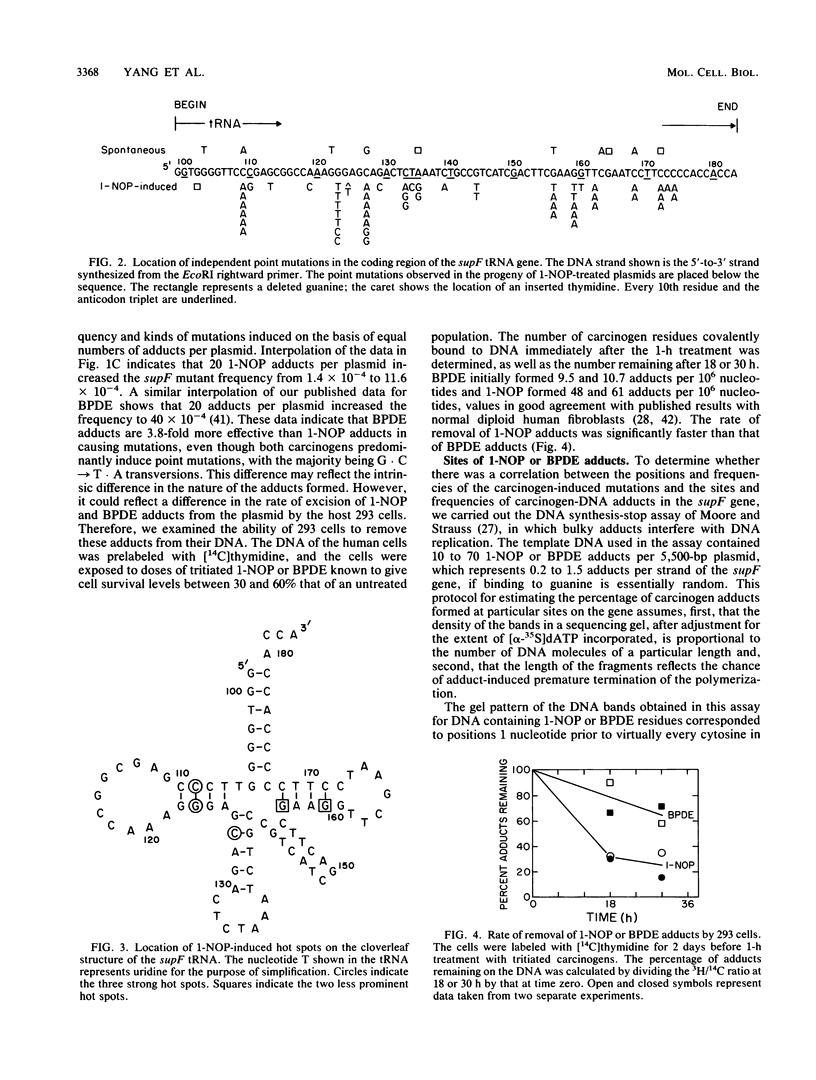

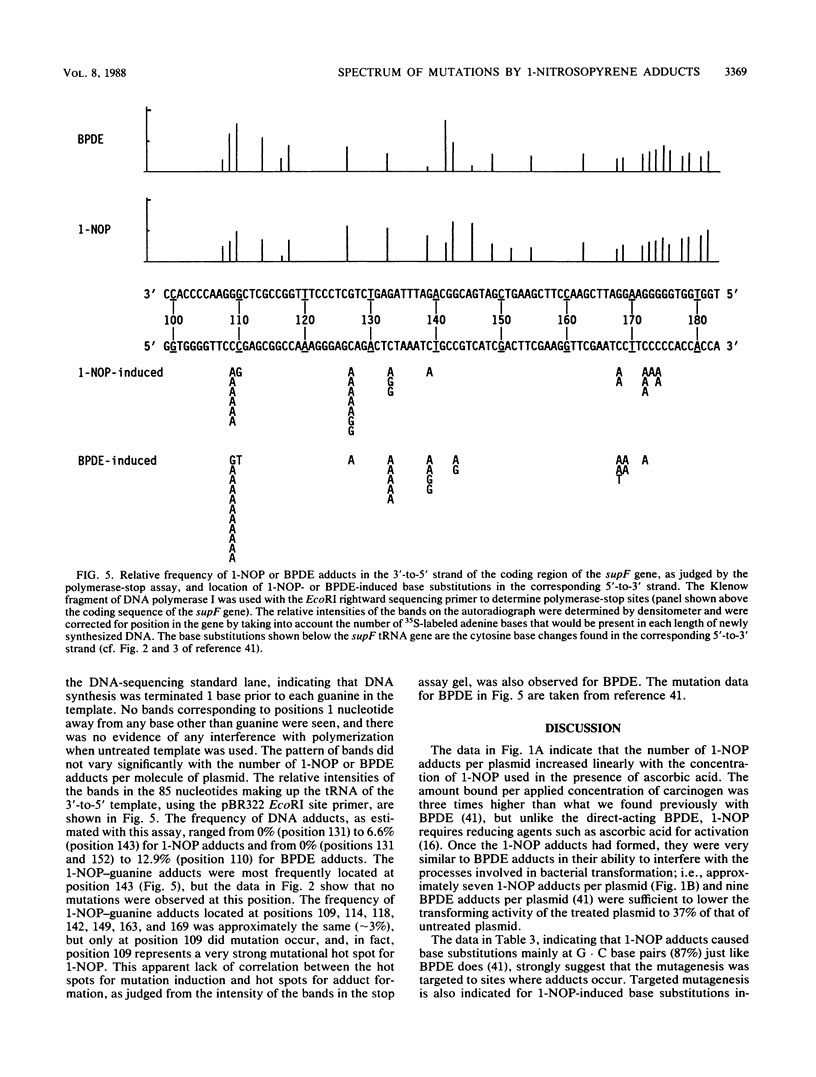

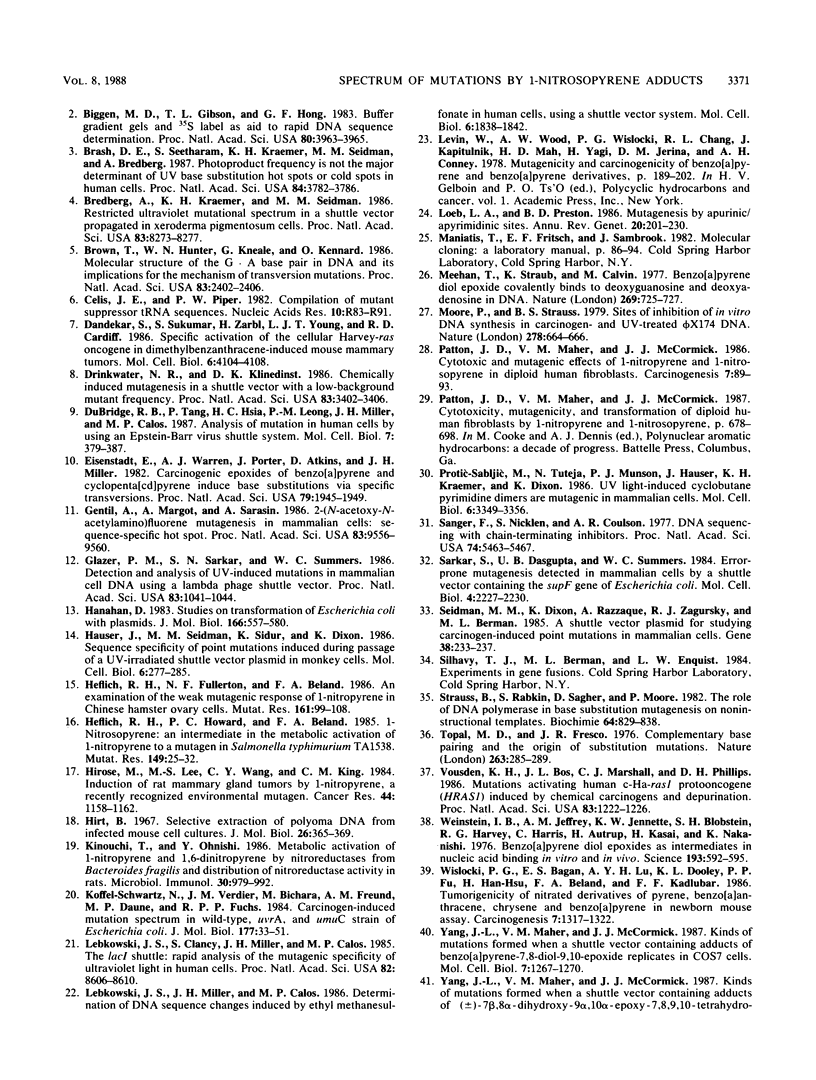

1-Nitropyrene has been shown in bacterial assays to be the principal mutagenic agent in diesel emission particulates. It has also been shown to be mutagenic in human fibroblasts and carcinogenic in animals. To investigate the kinds of mutations induced by this carcinogen and compare them with those induced by a structurally related carcinogen, (+/-)-7 beta,8 alpha-dihydroxy-9 alpha,10 alpha-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetra-hydrobenzo [a]pyrene (BPDE) (J.-L. Yang, V. M. Maher, and J. J. McCormick, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:3787-3791, 1987), we treated a shuttle vector with tritiated 1-nitrosopyrene (1-NOP), a carcinogenic mutagenic intermediate metabolite of 1-nitropyrene which forms the same DNA adduct as the parent compound, and introduced the plasmids into a human embryonic kidney cell line, 293, for DNA replication to take place. The treated plasmid, pZ189, carrying a bacterial suppressor tRNA target gene, supF, was allowed 48 h to replicate in the human cells. Progeny plasmids were then rescued, purified, and introduced into bacteria carrying an amber mutation in the beta-galactosidase gene in order to detect those carrying mutations in the supF gene. The frequency of mutants increased in direct proportion to the number of DNA-1-NOP adducts formed per plasmid. At the highest level of adduct formation tested, the frequency of supF mutants was 26 times higher than the background frequency of 1.4 X 10(-4). DNA sequencing of 60 unequivocally independent mutant derived from 1-NOP-treated plasmids indicated that 80% contained a single base substitution, 5% had two base substitutions, 4% had small insertions or deletions (1 or 2 base pairs), and 11% showed a deletion or insertion of 4 or more base pairs. Sequence data from 25 supF mutants derived from untreated plasmids showed that 64% contained deletions of 4 or more base pairs. The majority (83%) of the base substitution in mutants from 1-NOP-treated plasmids were transversions, with 73% of these being G . C --> T . A. This is very similar to what we found previously in this system, using BPDE, but each carcinogen produced its own spectrum of mutations. Of the five hot spots for base substitution mutations produced in the supF gene with 1-NOP, two were the same as seen with BPDE-treated plasmids. However, the three other hot spots were cold spots for BPDE-treated plasmids. Conversely, four of the other five hot spots seen with BPDE-treated plasmids were cold spots for 1-NOP-treated plasmids. Comparison of the two carcinogens for the frequency of supF mutants induced per DNA adduct showed that 1-NOP-induced adducts were 3.8 times less than BPDE adducts. However, the 293 cell excised 1-NOP-induced adducts faster than BPDE adducts.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beland F. A., Ribovich M., Howard P. C., Heflich R. H., Kurian P., Milo G. E. Cytotoxicity, cellular transformation and DNA adducts in normal human diploid fibroblasts exposed to 1-nitrosopyrene, a reduced derivative of the environmental contaminant, 1-nitropyrene. Carcinogenesis. 1986 Aug;7(8):1279–1283. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.8.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggin M. D., Gibson T. J., Hong G. F. Buffer gradient gels and 35S label as an aid to rapid DNA sequence determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Jul;80(13):3963–3965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.13.3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brash D. E., Seetharam S., Kraemer K. H., Seidman M. M., Bredberg A. Photoproduct frequency is not the major determinant of UV base substitution hot spots or cold spots in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Jun;84(11):3782–3786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredberg A., Kraemer K. H., Seidman M. M. Restricted ultraviolet mutational spectrum in a shuttle vector propagated in xeroderma pigmentosum cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Nov;83(21):8273–8277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T., Hunter W. N., Kneale G., Kennard O. Molecular structure of the G.A base pair in DNA and its implications for the mechanism of transversion mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Apr;83(8):2402–2406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celis J. E., Piper P. W. Compilation of mutant suppressor tRNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982 Jan 22;10(2):r83–r91. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.2.762-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandekar S., Sukumar S., Zarbl H., Young L. J., Cardiff R. D. Specific activation of the cellular Harvey-ras oncogene in dimethylbenzanthracene-induced mouse mammary tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Nov;6(11):4104–4108. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drinkwater N. R., Klinedinst D. K. Chemically induced mutagenesis in a shuttle vector with a low-background mutant frequency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 May;83(10):3402–3406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBridge R. B., Tang P., Hsia H. C., Leong P. M., Miller J. H., Calos M. P. Analysis of mutation in human cells by using an Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Jan;7(1):379–387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt E., Warren A. J., Porter J., Atkins D., Miller J. H. Carcinogenic epoxides of benzo[a]pyrene and cyclopenta[cd]pyrene induce base substitutions via specific transversions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Mar;79(6):1945–1949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentil A., Margot A., Sarasin A. 2-(N-acetoxy-N-acetylamino)fluorene mutagenesis in mammalian cells: sequence-specific hot spot. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Dec;83(24):9556–9560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazer P. M., Sarkar S. N., Summers W. C. Detection and analysis of UV-induced mutations in mammalian cell DNA using a lambda phage shuttle vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Feb;83(4):1041–1044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.4.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983 Jun 5;166(4):557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser J., Seidman M. M., Sidur K., Dixon K. Sequence specificity of point mutations induced during passage of a UV-irradiated shuttle vector plasmid in monkey cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jan;6(1):277–285. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.1.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflich R. H., Fullerton N. F., Beland F. A. An examination of the weak mutagenic response of 1-nitropyrene in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mutat Res. 1986 Jun;161(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(86)90104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflich R. H., Howard P. C., Beland F. A. 1-Nitrosopyrene: an intermediate in the metabolic activation of 1-nitropyrene to a mutagen in Salmonella typhimurium TA1538. Mutat Res. 1985 Mar;149(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(85)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose M., Lee M. S., Wang C. Y., King C. M. Induction of rat mammary gland tumors by 1-nitropyrene, a recently recognized environmental mutagen. Cancer Res. 1984 Mar;44(3):1158–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J Mol Biol. 1967 Jun 14;26(2):365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinouchi T., Ohnishi Y. Metabolic activation of 1-nitropyrene and 1,6-dinitropyrene by nitroreductases from Bacteroides fragilis and distribution of nitroreductase activity in rats. Microbiol Immunol. 1986;30(10):979–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb03028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffel-Schwartz N., Verdier J. M., Bichara M., Freund A. M., Daune M. P., Fuchs R. P. Carcinogen-induced mutation spectrum in wild-type, uvrA and umuC strains of Escherichia coli. Strain specificity and mutation-prone sequences. J Mol Biol. 1984 Jul 25;177(1):33–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebkowski J. S., Clancy S., Miller J. H., Calos M. P. The lacI shuttle: rapid analysis of the mutagenic specificity of ultraviolet light in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Dec;82(24):8606–8610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebkowski J. S., Miller J. H., Calos M. P. Determination of DNA sequence changes induced by ethyl methanesulfonate in human cells, using a shuttle vector system. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 May;6(5):1838–1842. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.5.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb L. A., Preston B. D. Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:201–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan T., Straub K., Calvin M. Benzo[alpha]pyrene diol epoxide covalently binds to deoxyguanosine and deoxyadenosine in DNA. Nature. 1977 Oct 20;269(5630):725–727. doi: 10.1038/269725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore P., Strauss B. S. Sites of inhibition of in vitro DNA synthesis in carcinogen- and UV-treated phi X174 DNA. Nature. 1979 Apr 12;278(5705):664–666. doi: 10.1038/278664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton J. D., Maher V. M., McCormick J. J. Cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of 1-nitropyrene and 1-nitrosopyrene in diploid human fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis. 1986 Jan;7(1):89–93. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protić-Sabljić M., Tuteja N., Munson P. J., Hauser J., Kraemer K. H., Dixon K. UV light-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are mutagenic in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Oct;6(10):3349–3356. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.10.3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Dasgupta U. B., Summers W. C. Error-prone mutagenesis detected in mammalian cells by a shuttle vector containing the supF gene of Escherichia coli. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Oct;4(10):2227–2230. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.10.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman M. M., Dixon K., Razzaque A., Zagursky R. J., Berman M. L. A shuttle vector plasmid for studying carcinogen-induced point mutations in mammalian cells. Gene. 1985;38(1-3):233–237. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss B., Rabkin S., Sagher D., Moore P. The role of DNA polymerase in base substitution mutagenesis on non-instructional templates. Biochimie. 1982 Aug-Sep;64(8-9):829–838. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(82)80138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topal M. D., Fresco J. R. Complementary base pairing and the origin of substitution mutations. Nature. 1976 Sep 23;263(5575):285–289. doi: 10.1038/263285a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden K. H., Bos J. L., Marshall C. J., Phillips D. H. Mutations activating human c-Ha-ras1 protooncogene (HRAS1) induced by chemical carcinogens and depurination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Mar;83(5):1222–1226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein I. B., Jeffrey A. M., Jennette K. W., Blobstein S. H., Harvey R. G., Harris C., Autrup H., Kasai H., Nakanishi K. Benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxides as intermediates in nucleic acid binding in vitro and in vivo. Science. 1976 Aug 13;193(4253):592–595. doi: 10.1126/science.959820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wislocki P. G., Bagan E. S., Lu A. Y., Dooley K. L., Fu P. P., Han-Hsu H., Beland F. A., Kadlubar F. F. Tumorigenicity of nitrated derivatives of pyrene, benz[a]anthracene, chrysene and benzo[a]pyrene in the newborn mouse assay. Carcinogenesis. 1986 Aug;7(8):1317–1322. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.8.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. L., Maher V. M., McCormick J. J. Kinds of mutations formed when a shuttle vector containing adducts of benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide replicates in COS7 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Mar;7(3):1267–1270. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. L., Maher V. M., McCormick J. J. Error-free excision of the cytotoxic,mutagenic N2-deoxyguanosine DNA adduct formed in human fibroblasts by (+/-)-7 beta, 8 alpha-dihydroxy-9 alpha, 10 alpha-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Oct;77(10):5933–5937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.10.5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbl H., Sukumar S., Arthur A. V., Martin-Zanca D., Barbacid M. Direct mutagenesis of Ha-ras-1 oncogenes by N-nitroso-N-methylurea during initiation of mammary carcinogenesis in rats. 1985 May 30-Jun 5Nature. 315(6018):382–385. doi: 10.1038/315382a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]