Abstract

Despite recent studies showing depletion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) pool accompanied by increased intracellular ROS upon autophagy inhibition, it remains unknown whether autophagy is essential in the maintenance of other stem cells. Moreover, it is unclear whether and how the aberrant ROS increase causes depletion of stem cells. Here, we report that ablation of FIP200, an essential gene for autophagy induction in mammalian cells, results in a progressive loss of neural stem cells (NSCs) pool and impairment in neuronal differentiation specifically in the postnatal brain, but not the embryonic brain, in mice. The defect in maintaining the postnatal NSC pool was caused by p53-dependent apoptotic responses and cell cycle arrest. However, the impaired neuronal differentiation was rescued by anti-oxidant NAC treatment, but not by p53 inactivation. These data reveal a role of FIP200-mediated autophagy in the maintenance and functions of NSCs through regulation of oxidative state.

Keywords: Autophagy, ROS, conditional knockout, mouse models, neural stem cells

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian brain maintains the capacity to generate new neurons as a function of tissue homeostasis and after injury. This regenerative capacity derives from neural stem cells (NSCs) that reside primarily within the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles 1 and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) 2-4. In adult brain, quiescent NSCs give rise to transit-amplifying progenitor cells which rapidly proliferate and contribute to lineage-restricted neuroblasts for the production of new neurons 5,6. Although the process of neurogenesis in adult brain is well characterized, our understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms maintaining NSCs in postnatal brain is still incomplete.

FIP200 (FAK-family Interacting Protein of 200 kDa) is one component of the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200-Atg101 complex essential for the induction of mammalian autophagy 7,8. Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process in which bulk cytoplasmic materials were sequestered and delivered to lysosomes for degradation9,10. Recent studies suggested that autophagy plays an important role in maintaining cellular homeostasis in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), as conditional knockout of essential autophagy gene Atg7 or FIP200 results in depletion of HSCs associated with increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) 11,12. Nevertheless, it is unclear whether and how the aberrant ROS increase causes depletion of HSCs. Moreover, the role of ROS in NSCs is less clear as a recent study indicates that a high ROS level is required for self-renewal of NSCs 13.

Here, we showed that FIP200 deletion led to a progressive loss of NSCs and defects in neurogenesis in postnatal brains, accompanied by increased ROS and its target p53. Further, inactivation of p53 restored the pool of NSC, but not their neurogenesis defects whereas treatment with ROS scavenger N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) rescued both defective phenotypes. These studies implicate a role for FIP200-mediated autophagy in the maintenance and functions of NSCs through regulation of oxidative state.

Results

FIP200 Deletion Leads to Various Defects in the SVZ and DG

To study the role of autophagy in NSCs, we conditionally deleted FIP200, an essential gene for autophagy induction, in these cells by crossing the floxed FIP200 mice 14 with the hGFAP-Cre transgenic mice, which express Cre recombinase in radial glial cells 15. FIP200f/f;hGFAP-Cre (designated as FIP200hGFAP cKO) mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio without exhibiting any overt differences compared to littermates control (FIP200f/f and FIP200f/+;hGFAP-Cre, designated as Ctrl mice) up to 10 weeks of age. Western blotting analysis showed efficient deletion of FIP200 in the SVZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. S1A). To analyze potential autophagy defects, we first measured the accumulation of LC3-II in the SVZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice at P14, which had been treated with chloroquine from P7 to P14 to inhibit LC3-II degradation 16. Reduced LC3-II accumulation was found in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to that in Ctrl mice (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, increased amount of p62 was found in lysates from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, consistent with autophagy inhibition in these cells 16. The p62 and ubiquitin-positive aggregations were also detected in sections containing the SVZ and DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. 1B; and data not shown). Together, these results suggest defective autophagy in NSCs of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice.

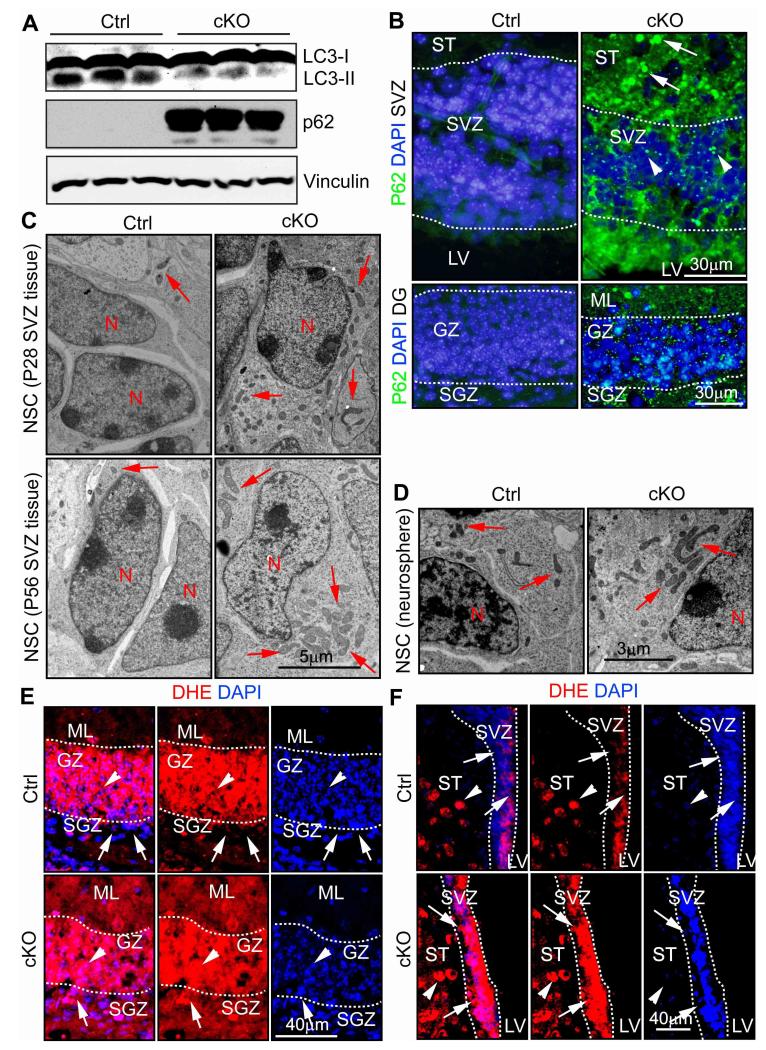

Figure 1. Deletion of FIP200 causes autophagy defects, increased mitochondria and ROS levels in NSCs.

(A) Lysates are extracted from the SVZ of three different Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice treated with chloroquine (CQ), and then analyzed by Western blot using anti-LC3 (top), anti-p62 (middle) or anti-Vinculin (bottom) antibodies. (B) Immunofluorescence of p62 and DAPI in the SVZ and DG of Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P28 (n= 3 mice for each). Lines indicate boundaries of the SVZ and GZ. The arrows and arrowheads mark larger and smaller p62+ aggregates in the ST and SVZ, respectively. (C) TEM of mitochondria in the SVZ tissue from Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P28 and P56 (n= 2 mice for each, >30 cells for each mouse). Arrows mark mitochondria. (D) TEM of mitochondria in cultured neurospheres from Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (n= 2 mice for each, >30 cells for each mouse). Arrows mark mitochondria. (E, F) Immunofluorescence of DHE and DAPI in the DG (E) and SVZ (F) of Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P28 (n= 5 mice for each). Lines indicate the boundaries of the GZ (E) and SVZ (F). Arrows mark cells in the SGZ (E) and SVZ (F) and arrowheads mark cells in surround regions (the GZ in E and the ST in F). Full-length blots are presented in the Supplementary Figure 11.

Because autophagy is essential for the clearance of damaged and/or excess mitochondria, which are a major source of intracellular ROS, we examined possible abnormalities of mitochondria and ROS level in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice. Analysis of cells in the SVZ by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed an increased number of mitochondria per nucleus in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to that in Ctrl mice at both P28 (18 ± 1 vs 8 ± 1) and P56 (17 ± 1 vs 11 ± 1) (Fig. 1C). At the later time point (P56), we also observed increased size and heterogeneity of mitochondria in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (arrows, lower panels). The aberrant accumulation of larger and more heterogeneous mitochondria was verified in neurospheres derived from NSCs of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. 1D, arrows). Quantification of multiple samples showed an approximately 50% increase in the number of mitochondria per cell in neurospheres from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (20±2), compared to that in Ctrl mice (13±1). We next determined ROS level in vivo using the fluorescent dye Dihydroethidium (DHE) as an indicator, as described previously 13,17. As shown in Fig. 1E, lower ROS level was found in the SGZ (arrows) compared to that in the surrounding GZ (arrowheads) in Ctrl mice (upper panels). High level of ROS was also observed in GZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (arrowheads, lower panels), but these were similar to those in Ctrl mice. Interestingly, however, elevated level of ROS was detected in the SGZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to Ctrl mice (arrows, lower panels). Similarly, ROS level was lower in the SVZ (arrows) than the surrounding striatum (ST; arrowheads) in Ctrl mice (upper panels), but was increased in the SVZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (lower panels)(Fig. 1F). Together, these results suggest that, as in other cell types11,18, deficient autophagy upon FIP200 deletion results in the increased mitochondrial mass and ROS in NSCs.

FIP200 Ablation Impairs NSC Maintenance and Neurogenesis

As ROS has been suggested as important regulators for the maintenance of various stem cells including NSCs 19-22, we performed histological examination of the DG and SVZ where postnatal NSCs reside. FIP200hGFAP cKO brains at P0 showed apparently normal morphology and cellular organization in the DG (circled with white lines) and SVZ (Figs. S1B and S1C) as well as all other brain regions (data not shown). At 4 weeks of age, however, the area of DG (circled with lines) was decreased in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to that in Ctrl mice (0.32±0.01 vs 0.17±0.01 mm2, n=5, >4 section/mouse, ***P<0.001)(Fig. 2A). Similarly, FIP200hGFAP cKO mice showed a thinner SVZ (marked by arrows) with decreased cellularity compared to Ctrl mice (177±7 vs 83±7 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, ***P<0.001)(Fig. 2A). Analysis of the SVZ by Toluidine Blue O staining as well as TEM confirmed the decreased cellularity in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. S1D-E). By 8 weeks of age, we also observed a significant decrease of the surface area of the olfactory bulb (OB) in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. S1F-G), suggesting a possible failure of neurogenesis driven by postnatal NSCs in these mice.

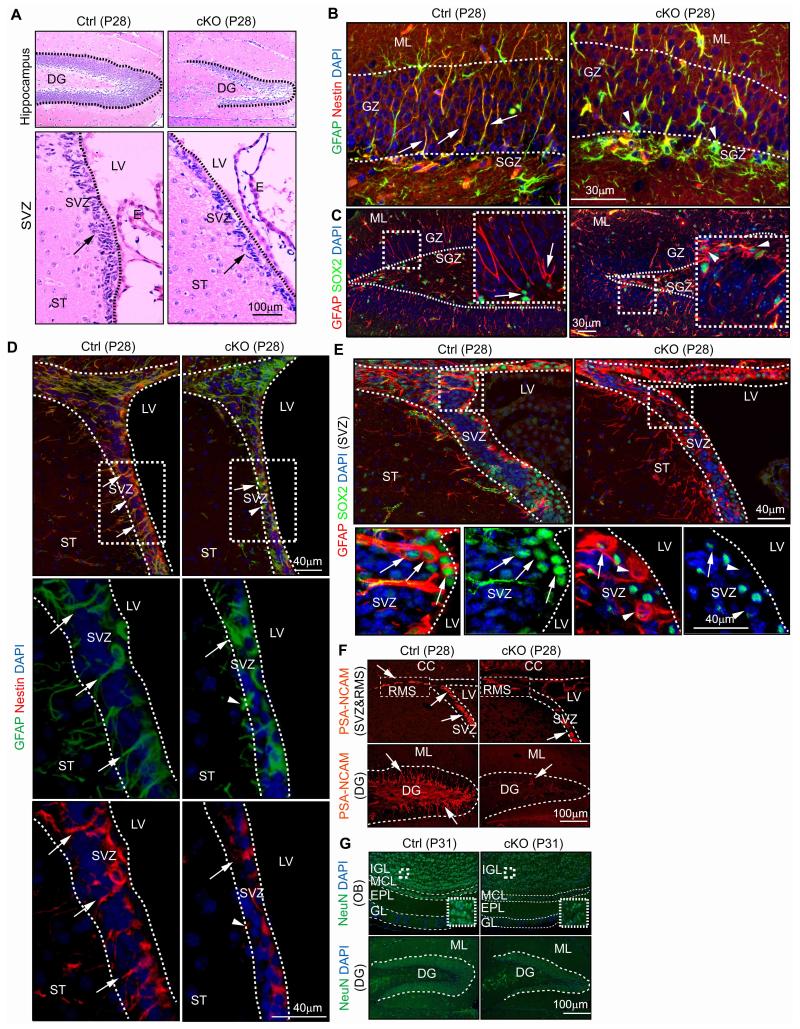

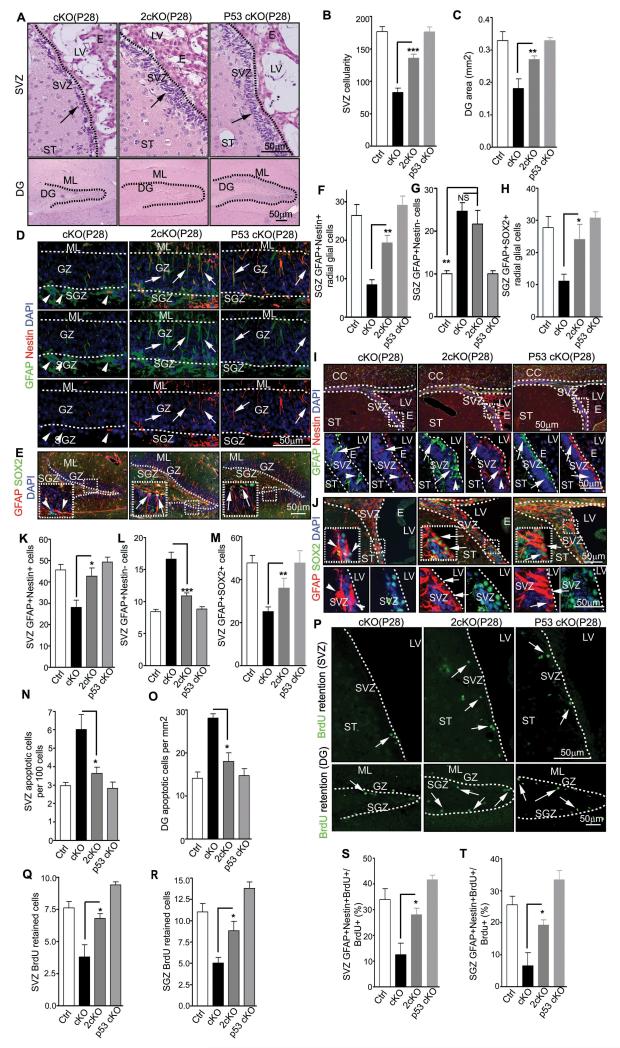

Figure 2. FIP200 ablation causes degeneration of the SVZ and DG as a result of NSCs deficiency.

(A) H&E staining of the DG and SVZ from Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P28. Lines indicate the boundaries of the DG and SVZ. Arrows mark cells in the SVZ. (B-E) Immunofluorescent staining with GFAP, Nestin, SOX2 and DAPI for the DG (B, C) and SVZ (D, E) from Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P28. The boxed areas in C-E are shown in more detail in insets (C) or panels below (D, E). Lines indicate boundaries of the GZ and SGZ (B), and SVZ (D, E). Arrows mark GFAP+/Nestin+ and GFAP+/SOX2+ NSCs with radial glial morphology (B, C), and arrowheads mark GFAP+/Nestin− and GFAP+/SOX2− astrocytes. (F) Immunofluorescent staining with PSA-NCAM for the RMS, SVZ, and DG of Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P28. Lines indicate the boundaries of the DG and SVZ. The boxed areas in upper panels indicate the RMS. Arrows mark PSA-NCAM+ cells in N. (G) Immunofluorescent staining with NeuN for the OB, and DG of Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P31. Lines indicate the layers of the OB and boundaries of the DG. The boxed areas in upper panels are shown in more detail for staining of NeuN in insets.

To further explore potential NSC defects in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, we determined the number of NSCs and their progenies by using various lineage markers. During embryonic development, radial glial cells in the ventricular zone (VZ) are NSCs and express RC2 23. Postnatally, radial glia are transformed into NSCs in the SVZ or DG as GFAP/Nestin positive cells, and are the source of continuous neurogenesis throughout the life 2. In the newborn mice (P0), comparable amount of radial glia/NSCs (RC2 positive and GFAP/Nestin positive), neuroblasts (PSA-NCAM positive), and Olig2 positive cells (oligodendrocytes and neural progenitor cells) were found in FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice (Fig. S2A-B). However, the pool of NSCs was significantly reduced in the DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P28, as measured by their radial glial morphology with expression of both GFAP and Nestin (27±3 vs 8±2 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, ***P<0.001)(Fig. 2B) or both GFAP and SOX2 (23±2 vs 12±1 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, **P<0.01)(Fig. 2C). Similar reductions of GFAP+/Nestin+ (48±3 vs 24±5 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, **P<0.01)(Fig. 2D) and GFAP+/SOX2+ (47±2 vs 25±2 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, **P<0.01)(Fig. 2E) NSCs were also found in the SVZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to Ctrl mice. Staining with PSA-NCAM showed a significant decrease of neuroblasts in the SVZ (65±2 vs 26±7 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, **P<0.01), RMS and DG (688±33 vs 190±30 cells/mm2, n=5, >4 section/mouse, ***P<0.001) of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to Ctrl mice (Fig. 2F), suggesting a defect in NSC-mediated neurogenesis. Consistent with this observation of impaired neurogenesis, a less densely populated RMS (Fig. S2C upper) as well as significantly reduced number of NeuN positive neurons in the internal granular layer (IGL) of the OB (4954±236 vs 3406±589 cells/mm2, n=5, >4 section/mouse, *P<0.05) and the granular zone (GZ) of the DG (601±25 vs 221±19 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, ***P<0.001) were found in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. 2G). In contrast to the decreased neurogenesis, we observed an increased number of GFAP+/Nestin− cells in the DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (10±1 vs 24±2 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, **P<0.01)(Fig. 2B). These cells in the GZ did not exhibit radial morphology, but attained astrocyte shape, and they were also detected as a dense ribbon in the SGZ (arrowheads). An increased number of GFAP+/Nestin− astrocytes were also found in the SVZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (arrowheads), with the concomitant loss of GFAP+/Nestin+ cells (7±1 vs 12±2 cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, **P<0.01)(Fig. 2D). In addition, increased GFAP staining was detected in the RMS of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, where the stream was filled with strong GFAP-positive bundles, instead of sparse GFAP positive processes in Ctrl mice (Fig. S2C lower). Besides neuronal lineages and astrocytes, we found that the number of Olig2 positive cells in the CC, RMS and DG were comparable between FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice (Fig. S2D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that deletion of FIP200 by hGFAP-Cre and aberrant increase in ROS result in progressive depletion of adult NSCs in postnatal brains. They suggest an essential function of FIP200 in postnatal NSC maintenance.

FIP200 Regulates NSC Apoptosis and Proliferation

To complement the above analysis using various markers and further study the role and potential mechanisms of FIP200 in the regulation NSC, we first examined self-renewal of NSC from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice by assessing the abilities of the dissociated neural cells from the SVZ of the mutant and control mice to form neurospheres in vitro. As shown in Figs. 3A-3C, the number and size of the primary neurospheres formed by the SVZ cells isolated at P0 were comparable between FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice, but the secondary neurospheres formed by the dissociated cells from the primary neurospheres were significantly decreased for FIP200hGFAP cKO compared to that of Ctrl mice. When the SVZ cells from P28 were analyzed, we found significant decreases in both primary and secondary neurosphere formations by FIP200hGFAP cKO neural cells (Figs. 3D and 3E). Similarly, an approximately 3-fold decrease in neurosphere formation was found for neural cells isolated from hippocampus (containing the DG) of P28 FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to those from Ctrl mice (data not shown). We also found that, consistent with observations in vivo (see Figs. 2B, 2D, 2F and 2G), culturing of dissociated cells from neurospheres in differentiation medium showed a significantly decreased differentiation to Tuj1+ neurons (7.3±0.3 vs 3.4±0.3%, n=3, >1000 cells/genotype, *P<0.05), but a slightly increased differentiation to astrocytes by neurospheres derived from FIP200hGFAP cKO NSCs compared to those from Ctrl NSCs (75±3 vs 82±5%, n=3, >1000 cells/genotype, P>0.05). These results suggest a potential role of FIP200 in the regulation of self-renewal and neurogenesis of NSCs.

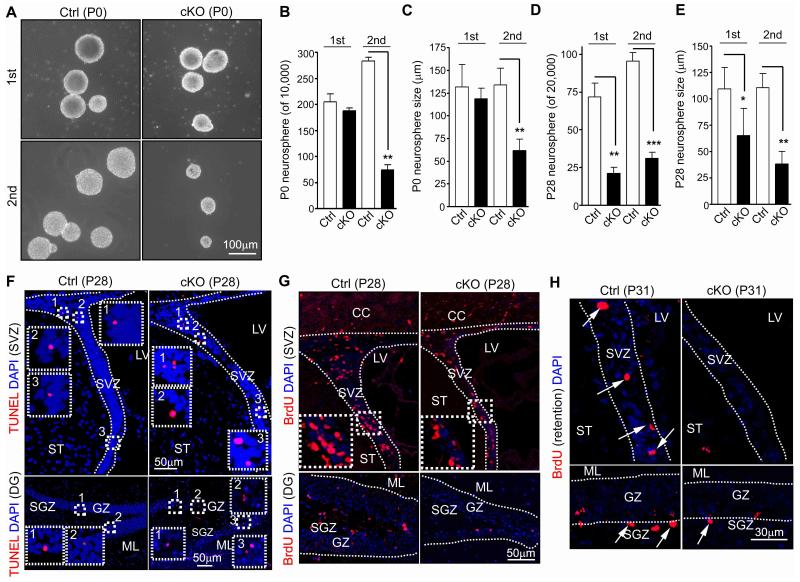

Figure 3. FIP200 deletion reduces the number of self-renewable NSCs.

(A-E) Primary (1st) and secondary (2nd) neurospheres from Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P0 and P28. Representative phase contrast images are shown in A (P0 neurospheres). Mean±SE of number (B, D) and size (C, E) of primary and secondary neurospheres from 3 independent experiments are shown (n= 3 mice for each). (F) TUNEL and DAPI staining of the SVZ and DG from Ctrl and FIP200hGFAPcKO mice at P28. Lines indicate the boundaries of the SVZ. The boxed areas are marked with numbers and shown in more detail for staining of TUNEL and DAPI in the SVZ and DG. (G) Short-term BrdU incorporation in the SVZ and DG of Ctrl and FIP200hGFAPcKO mice at P28. Lines indicate the boundaries of the SVZ and GZ. The boxed areas in upper panels are shown in more detail in the insets. (H) Long-term retention of BrdU in the SVZ and DG of Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at P31. Lines indicate the boundaries of the SVZ and GZ. Arrows mark BrdU+ cells. *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001.

Recent studies showed that FIP200 and several other Atg genes play a role in the survival of neurons and other cells 24-26. To determine whether an increased apoptosis is responsible for the progressive loss of NSCs in postnatal FIP200hGFAP cKO brains, we analyzed apoptosis in the SVZ, DG and other brain regions. At P0, several regions of FIP200hGFAP cKO brain, including the cortex, cerebellum, medulla and midbrain, exhibited a significant increase in apoptosis compared to that of Ctrl mice (Figs. S3A-F). Double staining with neural markers showed that the majority of apoptotic cells in both FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice were post-mitotic neurons as identified by NeuN+ staining, but not NSCs/progenitors (Nestin+) or oligodendrocytic cells (Olig2+) (Fig. S3G). In the SVZ and SGZ of the DG where NSCs reside and have no or few neurons, comparable levels of apoptosis were observed for FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice (Fig. S3H-I). In contrast to P0, a higher fraction of apoptotic cells was found in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to Crtl mice at P28 in both the SVZ (3.3±0.3 vs 4.6±0.4 apoptotic cells/100 cells, n=5, >500 cells/genotype, *P<0.05) and DG (15±2 vs 27±3 apoptotic cells/mm2, n=5, >4 section/mouse, *P<0.05)(Fig. 3F), suggesting that increased apoptosis upon FIP200 deletion is responsible for the progressive loss of NSCs in postnatal stages.

We next examined proliferation of NSCs in the SVZ and DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice, as more recent studies also suggested that deletion of FIP200 could result in decreased proliferation in breast cancer cells 18. At P0, comparable rate of proliferation were observed in the SVZ and DG of both FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice, as measured by either BrdU incorporation assay or Ki67 staining (Figs. S4A-D). At P28, fewer proliferative cells were found in the SVZ and DG in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to Ctrl mice. However, the fraction of proliferative cells was similar in the SVZ (27±2 and 25±1 BrdU+ cells/100 cells, n=5, >500 cells/genotype, P>0.05) or only slightly decreased in the DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to those of Crtl mice (62±2 vs 52±2 BrdU+ cells/mm2, n=5, >4 section/mouse, *P<0.05)(Fig. 3G)(and see Ki67 labeling in Figs. S4E-G), as the overall cellularity and area of these regions were also significantly decreased in the mutant mice. Because of the aberrantly increased astrogenesis in the SVZ and DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (see Figs. 2B and 2D) which could also proliferate, we further performed co-staining with neural markers to identify the nature of proliferative cells. We found that the proliferative NSCs (i.e. GFAP+Nestin+BrdU+ cells) as either a fraction of total BrdU+ (3.8±0.5 vs 1.3±0.4% [SVZ] and 4.2±0.6 vs 1.7±0.4% [SGZ], n=5, >200 BrdU+ cells/genotype and >4 section/mouse, respectively, ***P<0.001) or total GFAP+/Nestin+ (3.6±0.5 vs 1.2±0.4% [SVZ] and 3.8±0.6 vs 0.9±0.3% [SGZ], n=5, >200 GFAP+Nestin+ cells/genotype and >4 section/mouse, respectively, ***P<0.001 and **P<0.01, respectively) cells were indeed decreased in both the SVZ and DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to those in Ctrl mice. Similar reduction of dividing NSCs in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice was also observed by labeling proliferating cells using Ki67 (Figs. S4H-K). These data suggest that reduced proliferation could also contribute to the gradual loss of postnatal NSCs in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice.

Lastly, to validate the decreased number of NSCs in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice in vivo, we performed BrdU retention experiments by labeling with 3 consecutive injections at P7 followed by detection of BrdU+ cells in the SVZ and SGZ at 3 weeks after the pulse labeling. Similar number of BrdU+ cells was found in the SVZ and DG between FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice at P7 (data not shown). Interestingly, the number of BrdU retained cells in the lateral walls of the SVZ and SGZ of DG was significantly decreased in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to that in Ctrl mice (7.6±0.5 vs 3.3±0.3 [SVZ] and 11±1 vs 5±1 [SGZ] cells/section, n=5, >4 section/mouse, ***P<0.001)(Fig. 3H), suggesting a loss of self-renewing NSCs in vivo in the mutant mice. Together, these results suggest that FIP200 deletion reduced NSC self-renewal by affecting both apoptosis and proliferation, leading to progressive depletion of postnatal NSCs in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice.

P53 Ablation Rescues Self-renewal of FIP200-null NSCs

Although multiple signaling pathways could be affected by ROS, one important downstream target of ROS is the p53 tumor suppressor, which is a transcription factor that activates a plethora of genes whose products induce cell cycle arrest, differentiation, senescence, and apoptosis in response to DNA damage or other stress conditions 27-30. Therefore, it is possible that changes in p53 expression and activity could contribute to NSC defects upon FIP200 deletion and aberrant increase in ROS levels in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice. To test such a possibility, we first analyzed the level of p53 expression in neurospheres derived from FIP200hGFAP cKO and Ctrl mice. We found an increased expression of p53 in the neurospheres from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to those from Ctrl mice (Fig. 4A). Moreover, RT-qPCR analysis showed significant increases in the expression of several p53 target genes including p21, PUMA and Fas in neurospheres from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. 4B), although other targets like Bax, Tigar, and 14-3-3sigma did not show appreciable change (data not shown), when compared to neurospheres from Ctrl mice. These results suggest that NSC defects in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice may be dependent at least in part on the increased p53 and its downstream targets.

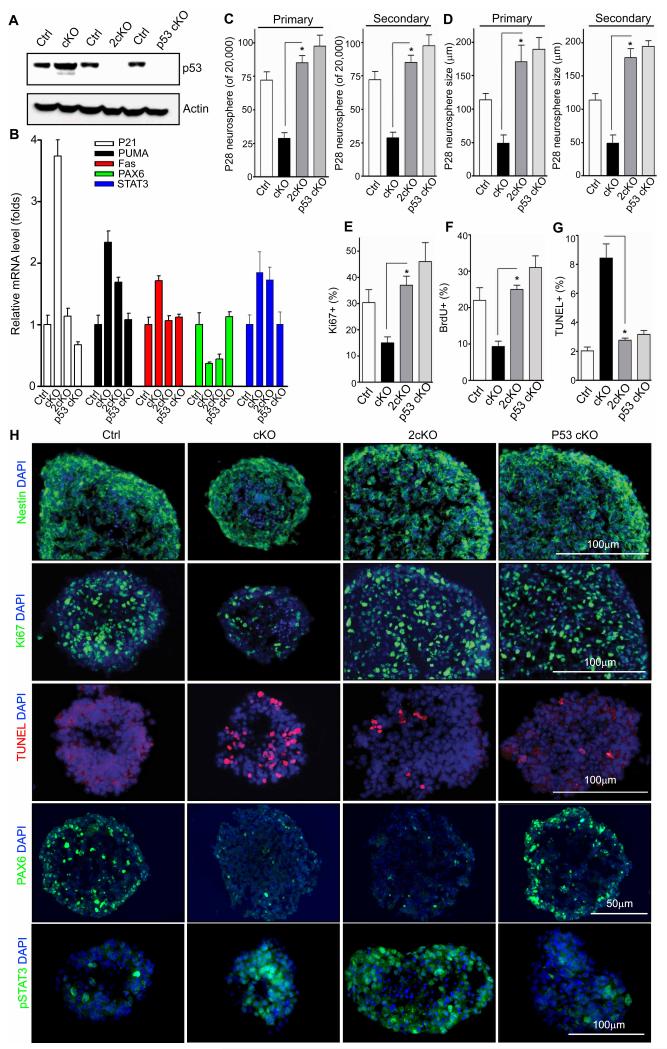

Figure 4. Inactivation of p53 rescues the defects of FIP200-null NSCs in vitro.

(A) Lysates are extracted from neurospheres of Ctrl, FIP200hGFAP cKO, p53hGFAP cKO, 2cKO mice and analyzed by Western blot using anti-p53 (top) and anti-actin (bottom) antibodies. (B) Mean±SE of relative mRNA level (normalized to Ctrl mice as 1) of p21, PUMA, Fas, PAX6 and STAT3 in neurospheres of Ctrl, FIP200hGFAP cKO, 2cKO, and p53hGFAP cKO mice are shown (n= 3 mice for each). (C, D) Mean±SE of the number (C) and size (D) of primary and secondary neurospheres from Ctrl, FIP200hGFAP cKO, 2cKO, and p53hGFAP cKO mice at P28 are shown (n=3 mice for each). (E-H) Neurospheres were frozen sectioned and analyzed by immunofluorescence for Nestin, Ki67, TUNEL, PAX6, phosphorylated STAT3, and DAPI, as indicated. Mean±SE of the percentage of Ki67+ (E), BrdU+ (F), and TUNEL+ (G) cells in neurospheres from Ctrl, FIP200hGFAP cKO, 2cKO, and p53hGFAP cKO mice are shown (n= 3 mice for each, counting of >500 cells for each mouse). Representative images are shown in H. *: p<0.01. Full-length blots are presented in the Supplementary Figure 11.

To explore the above possibilities directly, we generated double conditional KO mice with deletion of FIP200 and p53 (FIP200f/f;p53f/f;hGFAP-Cre; designated as 2cKO) as well as p53f/f;hGFAP-Cre (designated as p53hGFAP cKO) mice as a control by crossing FIP200hGFAP cKO and p53f/f mice (from NCI Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium). Both 2cKO and p53hGFAP cKO mice were obtained at the Mendelian ratio and analysis of neurospheres derived from these mice verified efficient deletion of p53 in NSCs (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this, the increased expression of p21, PUMA and Fas was also abrogated completely or partially in neurospheres from 2cKO mice (Fig. 4B). Analysis of the number and size of the neurospheres formed from 2cKO mice showed significant increases in both of these parameters compared to those from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Figs. 4C and 4D). The neurospheres were then sectioned and analyzed by staining with various markers. Ki67 staining (Figs. 4E and 4H) as well as BrdU incorporation assay (Fig. 4F) revealed a significant decrease of proliferative cells in neurospheres from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to those from Ctrl mice, which is consistent with observations in vivo (see Fig. 3G). Interestingly, the reduced proliferation of FIP200-null NSC/progenitors was completely rescued by p53 inactivation (Figs. 4E-F). Also similar to data from the DG and SVZ in vivo (see Fig. 3F), we observed a higher percentage of apoptotic cells in the neurospheres from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, which was dramatically reduced in the neurospheres from 2cKO mice (Figs. 4G-H). As expected, the majority of cells in neurospheres of all samples were Nestin positive (Fig. 4H) and RC2 positive (data not shown), confirming their NSC/progenitor nature. Together, these results indicate that the increased p53 expression after FIP200 deletion and aberrant ROS increase contribute to the defective self-renewal by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation of NSCs.

P53 Does not Mediate FIP200 Regulation of Neurogenesis

To validate the rescue of NSC defects of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice by p53 inactivation in vivo, we further examined the SVZ and DG in 2cKO mice. Histological analysis showed that the reduced cellularity of the SVZ and DG area in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice was rescued in 2cKO mice, up to 80% of the levels in Ctrl mice (Figs. 5A-5C). More importantly, the pool of NSCs in the DG of 2cKO mice was significantly increased compared to those of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, as measured by their radial glial morphology with double positive staining by Nestin and GFAP (Figs. 5D and 5F) or SOX2 and GFAP (Figs. 5E and 5H). Similarly, NSCs in the SVZ of 2cKO mice also increased from those of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice and to a comparable level as Ctrl mice, suggesting a more complete rescue in this region (Figs. 5I-5K and 5M). Consistent with data from neurospheres analysis in vitro, the increased apoptosis in SVZ and DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice was rescued in 2cKO mice (Figs. 5N and 5O). Moreover, analysis of the number of NSCs by BrdU retention and lineage tracing experiments confirmed that p53 inactivation was sufficient to restore NSC numbers in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Figs. 5P-5T). Together, these results suggest that the aberrantly increased p53 expression and apoptosis was mainly responsible for the shrinkage of the DG and SVZ and the reduction in number of NSCs in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice.

Figure 5. p53 deletion rescues NSCs defects in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice.

(A-C) H&E staining of the SVZ and DG of P28 mice (A). Arrows mark cells in the SVZ. Mean±SE of the SVZ cellularity (B) and DG area (C) per section are shown. (D-M) Immunofluorescence of the DG (D-H) and SVZ (I-M) of P28 mice(D, E, I, and J). The boxed areas are shown in more detail in insets (E) or panels below (I, J). Arrows mark GFAP+/Nestin+ and GFAP+/SOX2+ NSCs with radial glial morphology (D, E), and arrowheads mark GFAP+/Nestin− and GFAP+/SOX2− astrocytes. Mean±SE of the number of GFAP+/Nestin+ and GFAP+/SOX2+ radial glia (F, H), and NSCs (K, M), and GFAP+/Nestin− astrocytes (G, L) per section are shown. (N, O) Mean±SE of the number of TUNEL+ cells per 100 SVZ cells (N) or per 1 mm2 DG area (O) of P28 mice are shown. (P-R) BrdU retention in the SVZ and DG of P31 mice with BrdU+ cells marked by arrows (P). Mean±SE of the number of BrdU+ cells per section are shown in Q and R. (S, T) Mean±SE of percentage of GFAP+/Nestin+/BrdU+ cells of total BrdU retained cells in the SVZ (S) and SGZ (T) of P31 mice are shown. n= 5 mice, ≥4 sections/mouse, >500 cells counted/mouse in N, >20 BrdU+ cells counted/mouse in S and T. For staining panels, lines indicate the boundaries of the SVZ and DG (A) or GZ (D, E, K lower panels). NS: no significance; *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001.

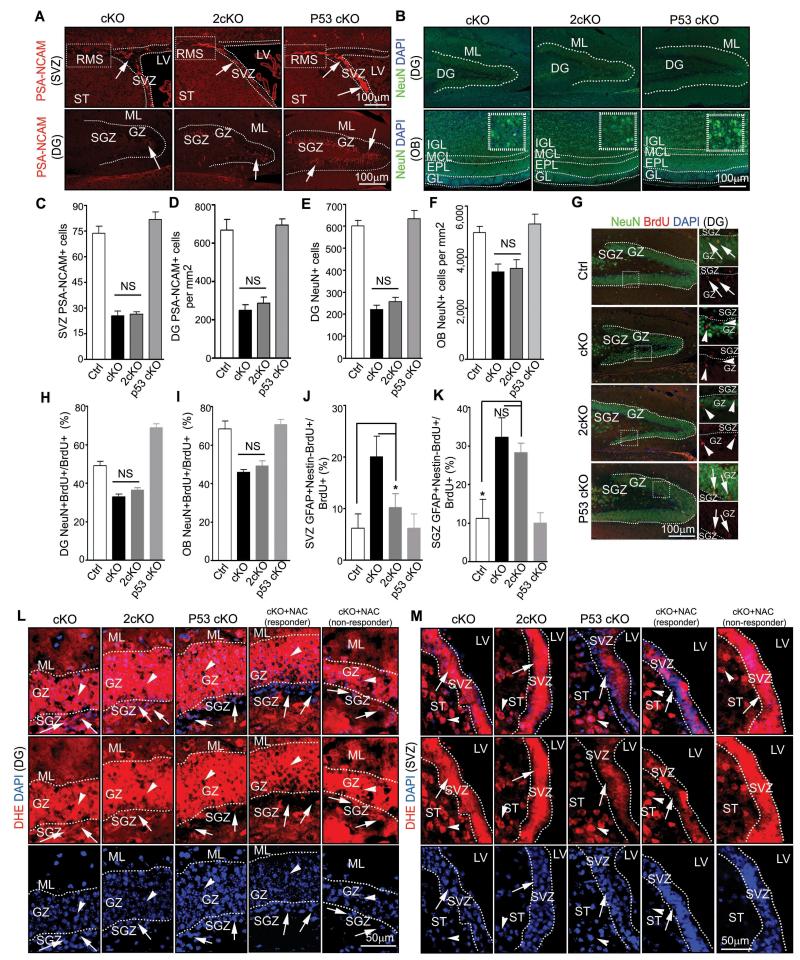

Despite the rescued number of NSCs observed in 2cKO mice, PSA-NCAM staining showed similarly decreased number of neuroblasts in the DG and SVZ of 2cKO mice as in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Figs. 6A, 6C-D). Consistent with this, the reduced number of NeuN positive neurons was also not rescued in 2cKO mice (Figs. 6B, 6E-F). These results suggest that p53 inactivation does not rescue defects in neuronal differentiation in FIP200-deficient NSCs. We therefore examined the neurogenesis step from neuroblasts to neurons by determining the fraction of neurons with BrdU label retention (i.e. those cells labeled as proliferating neuroblasts just before the last mitosis into the post-mitotic neurons) in the DG and OB of these mice. A significantly decreased fraction of NeuN+BrdU+ was found in the DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to those in Ctrl mice (Figs. 6G-H). Moreover, 2cKO mice showed similarly reduced fraction of NeuN+BrdU+ cells in the DG as those of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, supporting the notion that defects in neuronal differentiation of FIP200-null NSCs is independent of p53 activation. Similar results were obtained in OB (Figs. 6I and S5A).

Figure 6. FIP200 regulates NSCs differentiation in p53-independent manner.

(A-F) Immunofluorescence of PSA-NCAM (A) or NeuN (B) in the DG, SVZ, RMS, and OB of P28 mice.. Lines indicate boundaries of the DG (A, B), SVZ (A), and layers of the OB (B). The boxed areas in upper panels of A indicate the RMS. Arrows mark PSA-NCAM+ cells in A. Mean±SE of the number of PSA-NCAM+ cells (C, D) or NeuN+ cells (E, F) per section are shown. (G-I) Immunofluorescence of BrdU retention cells in the DG and OB of P31 mice. The boxed areas in left panels of G are shown in more detail in right panels. Arrows mark NeuN+/BrdU+ cells and arrowheads mark NeuN−/BrdU+ cells in the DG. Mean±SE of the percentage of NeuN+/BrdU+ cells of total BrdU retained cells in the DG (H) and OB (I). are shown. (J, K) Mean±SE of percentage of GFAP+/Nestin−/BrdU+ cells of total BrdU retained cells in the SVZ (J) and SGZ (K) are shown. (L, M) Immunofluorescence of DHE and DAPI in the DG (L) and SVZ (M) from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice with or without NAC treatment, 2cKO mice, and p53hGFAP cKO mice at P28. Lines indicate the boundaries of the GZ (L) and SVZ (M). Arrows mark cells in the SGZ (L) and SVZ (M) and arrowheads mark cells in surround regions (the GZ in L and the ST in M). n= 5 mice, ≥4 sections/mouse, >20 (H, J, K) or >200 (I) BrdU+ cells counted/mouse. NS: no significance; *: p<0.05.

Besides a lack of rescue for neurogenesis defects, we also noted that the aberrantly increased SVZ GFAP+Nestin− astrocytes in 2cKO mice were still at a level higher than those in Ctrl mice although they were reduced compared to that in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Figs. 5I and 5L). Also consistently, although the radial shaped cells were significantly rescued in GZ of 2cKO mice (arrows), the increased GFAP staining of cells with astrocyte morphology were still present in the SGZ of 2cKO mice in a similar amount as those in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (arrowheads)(Figs. 5D and 5G). Interestingly, examination of BrdU-retained cells (see Fig. 5P) also showed an increased fraction of GFAP+Nestin−BrdU+ cells in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice compared to those in Ctrl mice, which was also only partially reduced in the SVZ (Fig. 6J) and high at a comparable level in the DG (Fig. 6K) of 2cKO mice. These results suggest that the increased number of GFAP+ differentiated astrocytes caused by FIP200 deletion (and not rescued by p53 inactivation) was generated from NSCs (rather than proliferating or upregulating GFAP via a more indirect mechanism). Taken together, these results suggested that FIP200 regulates self-renewal of NSC and differentiation of NSCs and their progenies neuroblasts through p53-dependent and –independent mechanisms, respectively. They also implicate that other targets of increased ROS could be responsible for the p53-independent, differentiation defects in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice.

ROS Depletion Rescues NSC Defects in FIP200hGFAP cKO Mice

To investigate the hypothesis that the neuronal differentiation defects in 2cKO mice were caused by aberrantly high ROS but independent of p53, we first examined whether ROS levels were reduced by p53 inactivation in these mice as previous studies reported that p53 could regulate ROS and autophagy 29. We found that 2cKO mice exhibited comparably elevated ROS levels as those in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice in both the SGZ (Fig. 6L) and SVZ (Fig. 6M). Moreover, the increased p62 aggregates caused by FIP200 deletion and defective autophagy also remained in the SVZ and DG of 2cKO mice (Fig. S5B). Therefore, inactivation of p53 did not rescue the autophagy defects and consequent ROS increase in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice. These results are consistent with the idea that aberrant ROS levels was genetically upstream of increased p53 expression and that other downstream targets of ROS could be responsible for the p53-independent NSC differentiation and neurogenesis defects in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice.

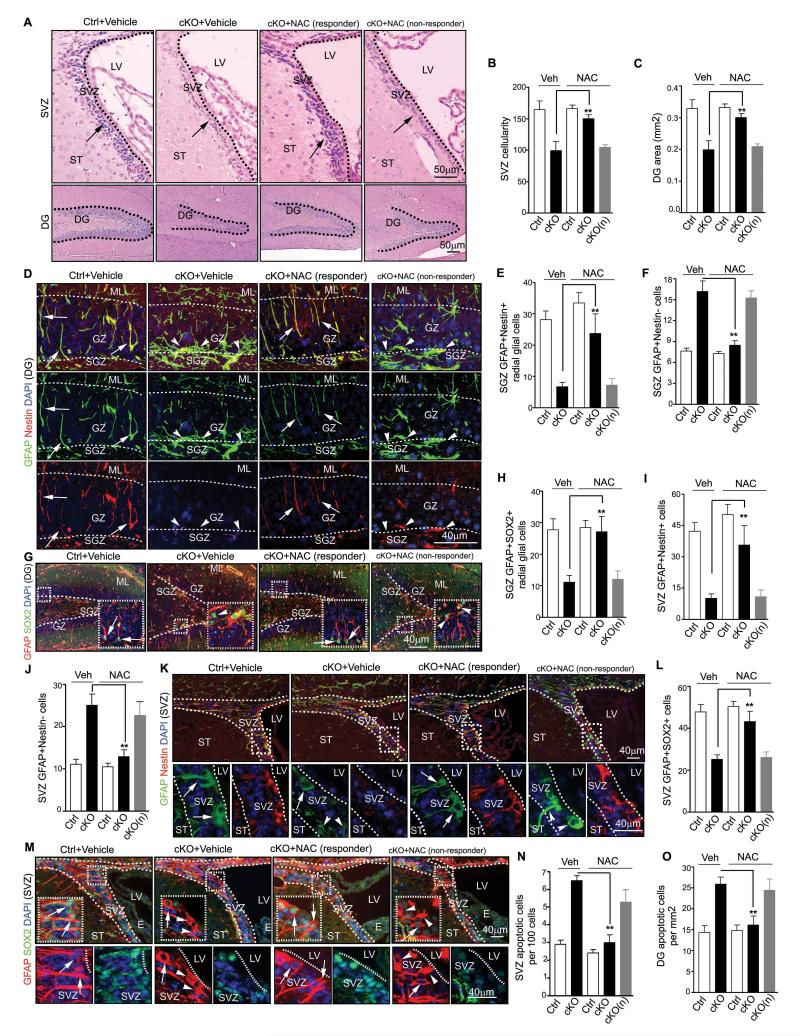

To directly test the above hypothesis more rigorously, we employed a widely used anti-oxidant, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), to scavenge ROS and examine the effects on NSCs. After daily treatment of NAC for 21 days starting from P7, the elevated ROS in the DG and SVZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice were decreased in the majority of samples (11 out of 16 mice, designated as responder and the remaining minority fraction as non-responder) (Figs. 6L and 6M, arrows in responder panels), whereas the levels of ROS in these regions of Ctrl mice were not affected and remained low (data not shown). As expected, treatment with NAC reversed the elevated expression of p53 and its targets p21, PUMA and Fas in neurospheres from responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. S6A-D). Analysis of the number and size of the neurospheres showed that NAC restored both of these parameters in FIP200-null NSCs from responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice to a similar level as those from Ctrl mice (Fig. S6E-F). Consistent with these data from neurosphere culture studies in vitro, histological analysis showed restoration of the SVZ cellularity and the DG area in NAC-treated responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice to comparable levels as those in Ctrl mice (Figs. 7A-7C). Moreover, the decreased pool of NSCs in the DG was also rescued by NAC in responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice to a similar level as those in Ctrl mice, as measured by Nestin/GFAP and SOX2/GFAP double positive cells with the radial glial morphology (Figs. 7D, 7E, 7G and 7H). Similar results were obtained for NSCs in the SVZ of responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Figs. 7I, 7K-M). Lastly, the increased apoptosis in SVZ and DG of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice was also reversed NAC in responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Figs. 7N and 7O). Together, these results indicate that suppression of the aberrant ROS levels and consequent p53 increase by NAC treatment rescued defective self-renewal caused by FIP200 deletion.

Figure 7. Rescue of NSCs maintenance in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice by scavenging abnormally elevated ROS.

(A-C) H&E staining of the SVZ and DG of P28 mice treated by NAC or vehicle control. Lines indicate boundaries for the SVZ and DG. Arrows mark cells in the SVZ. Mean±SE of the SVZ cellularity (B) and DG area (C) per section are shown. (D-M) Immunofluorescence of the DG (D-H) and SVZ (I-M) of P28 mice treated by NAC or vehicle control. Representative images are shown in D, G (DG) and K, M (SVZ). Lines indicate boundaries of the GZ (D, G) and SVZ (K, M). The boxed areas in G, K and M are shown in more detail in insets (G) or panels below (K and M). Lines indicate boundaries of the GZ (D, G) and SVZ (K, M). Arrows mark GFAP+/Nestin+ and GFAP+/SOX2+ NSCs with radial glial morphology (D, G), and arrowheads mark GFAP+/Nestin− and GFAP+/SOX2− astrocytes. Mean±SE of the number of GFAP+/Nestin+ and GFAP+/SOX2+ radial glia (E, H), and NSCs (I, L), and GFAP+/Nestin− astrocytes (F, J) per section are shown. (N, O) Mean±SE of the number of TUNEL+ cells per 100 SVZ cells (N) or per 1 mm2 DG area (O) of P28 mice treated by NAC or vehicle control are shown. n= 5 mice, ≥4 sections/mouse, >500 cells counted/mouse in N. For all panels, cKO(n): NAC non-responder cKO mice.

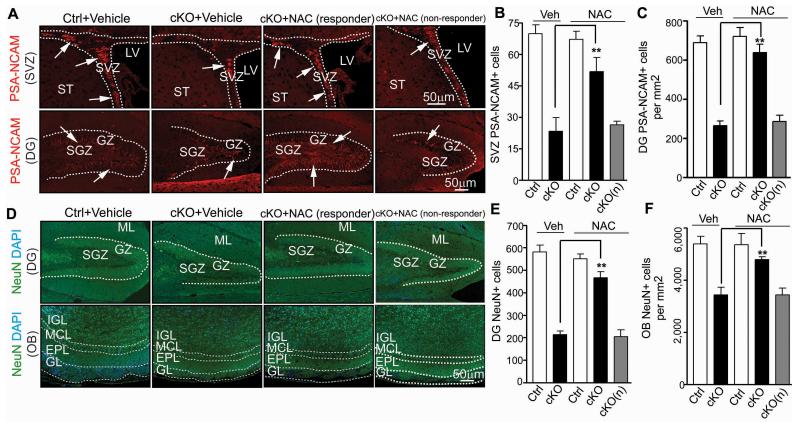

More importantly and in contrast to p53 inactivation, reversal of elevated ROS by NAC also alleviated the defects in neurogenesis and differentiation of NSCs in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice. As shown in Figs. 8A-C, the reduced numbers of neuroblasts in the DG, SVZ and RMS (arrows) of responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice were significantly increased after NAC treatment. Similarly, the number of neurons in the DG and OB was also rescued in responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice upon NAC treatment (Figs. 8D-F). Consistent with these results, the fraction of NeuN+ neurons retaining BrdU labelling was also rescued in responder (but not non-responder) FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, supporting restoration of the neuronal production in these mice by NAC treatment (Fig. S6G-J). Besides rescued neurogenesis defects, the aberrant increase of astrogenesis in the mutant mice was abrogated, as the elevated number of astrocytes (i.e. GFAP+/Nestin− cells; arrowheads) was reduced to a similar level as in Ctrl mice after NAC treatment (Figs. 7D, 7F, 7J-K).

Figure 8. Rescue of NSC neurogenesis defects in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice by NAC.

Immunofluorescence of PSA-NCAM (A-C) or NeuN (D-F) in the DG, SVZ, RMS and OB of P28 mice treated by NAC or vehicle control. Representative images are shown for PSA-NCAM (A) and NeuN (D). Lines indicate boundaries of the DG (A, D), SVZ (A)and layers of the OB (D). Arrows mark PSA-NCAM+ cells in A. Mean±SE of the number of PSA-NCAM+ cells in SVZ (B) and DG (normalized to 1 mm2 area) (C), and the number of NeuN+ cells in DG (E) and IGL of OB (normalized to 1 mm2 area) (F) per section are shown (n= 5 mice for each; ≥4 sections for each mouse). cKO(n): NAC non-responder cKO mice. **: p<0.01.

A number of transcription factors and signaling pathways such as the Notch and BMP pathways play important roles in the regulation of NSCs differentiation and neurogenesis in recent studies31,32. Therefore, we next examined the expression of several genes of these pathways in neurospheres derived from Ctrl, FIP200hGFAP cKO and 2cKO mice as well as those from FIP200hGFAP cKO treated with NAC (both responder and non-responder) to explore the potential p53-independent mechanisms regulating NSC differentiation downstream of elevated ROS after FIP200 deletion. We found that the expression of Notch and several target genes were not changed upon FIP200 deletion (Fig. S7), suggesting that Notch pathway is not involved. Interestingly, the expression of PAX6 (a pro-neurogenesis transcription factor33,34) was decreased in neurospheres from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, as measured for both mRNA and protein levels (Figs. 4B and 4H). Moreover, the expression and activity of STAT3, which both cooperates and can activate the BMP pathway to promote astrogenesis35, were increased in FIP200hGFAP cKO neurospheres as shown by measuring mRNA expression and pSTAT3 levels (Figs. 4B and 4H). The changes for PAX6 and STAT3 were not rescued by p53 inactivation in 2cKO mice (Figs. 4B and 4H), suggesting that they were regulated in a p53-independent manner. Consistent with the rescue of both NSC maintenance and differentiation phenotypes, NAC treatment of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice restored expression of PAX6 and STAT3 in responder (but not non-responder) mice to comparable levels as those in Ctrl mice (Fig. S8A-B). We further tested the effect of NAC treatment of FIP200-null NSCs from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice in vitro, where unlike the situation (with a small fraction of non-responders) in vivo, all cells are expected to respond to the treatment uniformly. As expected, NAC reversed the elevated expression of p53 and its targets p21, PUMA and Fas in neurospheres from FIP200-null NSCs (Fig. S8C). NAC also rescued defects in secondary neurosphere propagation of NSCs from P0 FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. S8D-F). Similar to results in responder mice, NAC reversed the abnormal expression levels of PAX6 and STAT3 in these cells (Fig. S8G-H). These results suggest that FIP200-mediated autophagy may support neurogenesis and astrogenesis by maintaining the normal levels and activities of PAX6 and/or STAT3 in a p53-independent manner.

Taken together, our studies demonstrate that suppression of abnormal increase in ROS rescued both p53-dependent and –independent NSC defects in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, implicating that the increased ROS after FIP200 deletion is most likely an underlying molecular mechanism for the deficient self-renewal and differentiation of NSCs in these mice.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate a critical role of autophagy in controlling ROS level in postnatal NSCs for their maintenance and differentiation. Deletion of the essential autophagy gene FIP200 by hGFAP-Cre resulted in aberrant increase in ROS and gradual depletion of NSCs. Moreover, inhibition of autophagy by Spautin-1 36 significantly reduced neurosphere formation from the SVZ cells in culture (Fig. S9A-C), further supporting autophagy function of FIP200 in NSC regulation. Unlike the increased proliferation upon FIP200 deletion in HSCs11, FIP200-null NSCs with elevated ROS exhibited decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis, which were rescued by NAC treatment, suggesting that deficiency in autophagy and increased ROS may impact on NSCs and HSCs through distinct cellular mechanisms. Despite the previous studies in HSCs 11,12, the present study is the first to provide the mechanistic basis underlying the progressive loss of NSCs or any other stem cells caused by aberrant increase of ROS.

It is interesting that FIP200 deletion caused gradual depletion of postnatal NSCs, but did not affect embryonic NSCs. Because deletion of FIP200 in NSCs would also lead to its inactivation in their progenies including astrocytes, which mostly differentiate and proliferate in the postnatal brain, one intriguing possibility is that FIP200-null astrocytes affected postnatal NSCs in the adult brain. However, co-culture of embryonic NSCs with neonatal astrocytes from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice did not significantly affect their neurosphere formation when compared to those co-cultured with astrocytes from Ctrl mice or without co-culture (Fig. S9D), suggesting that such potential effects from FIP200-null astrocytes are less likely and that the different response to FlP200 deletion between embryonic and postnatal NSCs is mostly intrinsic to NSCs. It is also possible that both embryonic and postnatal NSCs are susceptible to autophagy inhibition and aberrant ROS elevation, but the accumulation of ROS is a gradual process in the autophagy-deficient NSCs. Therefore, damages could only be observed in postnatal NSCs, but not embryonic NSCs, due to longer time for ROS accumulation to reach a threshold level in these cells. Lastly, an alternative but not mutually exclusive possibility is that embryonic and postnatal NSCs may have intrinsic differences in their autophagy activity and consequently differential responses to loss of FIP200 in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice. Indeed, analysis of brain samples from embryonic and postnatal FIP200hGFAP cKO mice showed that autophagy activity in regions containing NSCs is minimal at E17.5, but can be readily detected at P14 with further increase at P28, as measured by LC3-II levels (Fig. S9E). Interestingly, inactivation of autophagy by FIP200 deletion caused accumulation of p62 as well as elevated ROS levels in P14 and P28 SVZ, but not E17.5 VZ, where postnatal and embryonic NSCs reside respectively, in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Figs. S9F and S10A). Therefore, the very low level of autophagy activity in embryonic NSCs and thus the absence of elevated ROS upon FIP200 deletion in these cells could account for their resistance to loss of FIP200 and autophagy.

Our findings here that treatment of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice with NAC rescued all NSC defects in the majority of mice and that the rescue of NSC defects correlated with the ROS levels in the treated mice (i.e. rescued in responders but not in a small fraction of non-responders) highlight the important role ROS in the regulation of NSCs. Consistent with our findings, several previous studies suggested a role of increased ROS in NSC defects upon deletion of other genes including FoxO family members 37,38,39. Interestingly, recent studies suggested that FoxO1 could control autophagy in cancer cells 40 and that FoxO3 regulated autophagy in muscles 41. Thus, it will be interesting to examine possible autophagy defects in these mice, which might also contribute to the ROS elevation and NSC phenotypes caused by FoxO-deficiency.

Our studies also implicate that autophagy is important for NSC maintenance and differentiation by regulating oxidative stress under physiological conditions. Adult NSCs localize in hypoxic niches, e.g. the SGZ of the DG 42. As hypoxia could cause elevation of ROS and oxidative damage, it would be important for NSCs to keep a lower ROS level especially in quiescence. Indeed, we observed lower ROS levels in the SVZ and SGZ compared to cells in surrounding regions of Ctrl mice, and they were significantly elevated in FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, suggesting that autophagy may limit ROS increase to protect NSCs in the hypoxic niche. In contrast to our observation and other studies43, a recent report showed higher ROS levels in NSCs within the SVZ, which was suggested to associate with the proliferative or “activated” state of NSCs 13. Interestingly, we also observed some heterogeneity in ROS levels in the SVZ (Fig. 1F), although ROS levels were uniformly low in the SGZ (Fig. 1E) that was not examined in 13. It is therefore possible that NSCs with the higher ROS level in the SVZ are proliferative whereas those with lower levels are quiescent. Interestingly, further analysis by triple labeling showed very low level of ROS in GFAP+/SOX2+ NSCs of Ctrl SVZ (Fig. S10B, left panels), which exhibited some heterogeneity (i.e. slight DHE staining for the NSC at left [arrows] but not for the NSC at right [asterisks]). In contrast, elevated ROS level was found in GFAP+/SOX2+ NSCs in the SVZ of FIP200hGFAP cKO mice (Fig. S10B, right panels), supporting the hypothesis that aberrantly elevated ROS is responsible for the gradual depletion of postnatal NSCs. Future studies will be necessary to resolve the potentially complex regulation of NSCs by ROS in both positive and negative manners.

Previous studies suggested p53 and its target genes p21 and PUMA as negative regulators for self-renewal of various stem cells including NSCs 44-46. Ectopic expression of constitutively active p53 led to depletion of various adult stem cells, including NSCs 45 whereas germline p53 deletion increased proliferation, survival and self-renewal of NSCs 46,47. However, our study showed that conditional inactivation of p53 in somatic cells exhibited little or no phenotypes in the SVZ and DG, consistent with a previous study that employed the same hGFAP-Cre-mediated inactivation of p53 48. These results suggest that p53 does not normally regulate NSC functions unless these stem cells are under stress conditions such as in culture (as in previous studies) or high levels of ROS (this study).

FIP200 deletion also affected NSC differentiation with reductions in neurogenesis, consistent with previous studies showing altered differentiation in HSCs with loss of FIP200 or Atg7 11,12 or preadipocytes lacking Atg5 or Atg7 49,50. In FIP200hGFAP cKO mice, the diminished production of new neurons could be the consequence of reduced pool of NSCs, decreased proliferation or survival of NSCs or their progeny, or reduced neuronal lineage commitment. Interestingly, while it rescued the deficient pool of NSCs, p53 ablation did not restore the defective neurogenesis, suggesting that the reduced NSC pool is not solely responsible and that additional ROS targets are important for the defective neurogenesis. Interestingly, we found that the pro-neurogenesis transcription factor PAX6 was decreased whereas the expression and activity of STAT3, which both cooperates and can activate the BMP pathway to promote astrogenesis35, were increased in neurospheres derived from FIP200hGFAP cKO mice. Moreover, the altered expression of PAX6 and STAT3 was rescued by NAC treatment, but not by p53 ablation, suggesting that elevated ROS may decrease neurogenesis and/or increase astrogenesis through PAX6 and/or BMP signaling in a p53-independent manner.

In conclusion, our study identified a role for FIP200-dependent autophagy in the maintenance of postnatal, but not embryonic NSCs, and in neurogenesis of NSCs. Our results also demonstrate that autophagy is a critical mechanism in controlling ROS levels to ensure the self-renewal of postnatal NSCs.

Methods

Mice

FIP200f/f, p53f/f and hGFAP-Cre transgenetic mice were described previously 48,51. Male and female mice with 50% FVB and 50% C57/B6 backgrounds were used in experiments. Age- and littermate-matched control and mutant mice were randomly collected based on their genotypes. Mice were housed and handled according to local, state, and federal regulations. All experimental procedures were carried out according to the guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of Michigan. Mice genotyping for FIP200, p53 and Cre alleles were performed by PCR analysis of tail DNA, essentially as described previously 24,51.

Antibodies and Reagents

Primary antibodies used were mouse anti-Nestin (1:50, Rat-401), anti-PSA-NCAM (1:50, 5A5), anti-BrdU (1:200, G3G4), anti-RC2 (1:100, C-19)(all from DSHB, IA), Rhodamine conjugated anti-BrdU (1:200, Millipore, MA), anti-beta-actin (1:5000), anti-vinculin (1:5000; both from Sigma, MO) and anti-NeuN (1:500, Millipore, MA); rabbit anti-p53 (1:1000, Leica, Germany), anti-Ki67 (1:100, Spring Bioscience, CA), anti-p62 (1:200 for immunofluorescent and 1:1000 for Western blot, Enzo, PA), anti-GFAP (1:400, DAKO, CA), anti-LC3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, MA), anti-PAX6 (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-Tuj1 (1:100, Sigma, MO), anti-SOX2 (1:500, Millipore, MA) and anti-phosphor-STAT3 (Tyr 705) (1:100, Cell Signaling, MA); rat anti-Ki67 (1:100, Biolegend, CA). Rabbit anti-FIP200 (1:1000) and rabbit anti-Olig2 (1:500) were as described previously 18,24,48. Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC (1:400), goat anti-rabbit IgG-Texas red (1:400), goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC (1:200), goat anti-mouse IgG-Texas Red (1:400), goat anti-mouse IgM-Rhodamine (1:200), goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (1:5000), goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:5000)(all from Jackson Immunology, PA). Chloroquine, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and Dihydroethidium (DHE) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Histology, Immunofluorescence (IF) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Mice were euthanized using CO2, and a complete tissue set was harvested during necropsy. Fixation was carried out for 16 hr at 4°C using 4% (w/v) freshly made, pre-chilled PBS-buffered paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brain tissues were all sagital sectioned and then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm. Slides from histologically comparable positions (triangular lateral ventricle with intact RMS) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for routine histological examination or left unstained for immunofluorescence (IF). H&E stained sections were examined under a BX41 light microscope (Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, PA), and images were captured with an Olympus digital camera (model DP70) using DP Controller software (Version 1.2.1.10 8). For IF, unstained tissues were first deparaffinized in 3 washes of xylene (3 min each) and then were rehydrated in graded ethanol solutions (100, 95, 70, 50, and 30%). After heat-activated antigen retrieval (Retriever 2000, PickCell Laboratories B.V., Amsterdam, Holland) according to the manufacturer’s specifications, sections were treated with Protein Block Serum Free (Dako Corp, CA) at room temperature for 10 min. Slices were then incubated with the primary antibodies at 4°C for 16 hr in a humidified chamber, washed in PBS for 3 times (5 min each) and incubated with the 1:200 secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. After incubation with secondary antibodies and washed in PBS for 3 times (5 min each), nuclei were stained with DAPI and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, CA). Digital photography was carried out as described previously (Wei et al., 2011).

The TEM studies of the SVZ samples were performed as described previously 24. In brief, wild type and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice were perfused through the heart with a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 1.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). Brains were removed and postfixed for 2 hr with the same fixative. Brains were sectioned as 200 μm slices with a vibratome (Leica, Germany). Before postfixation for 1 hr with 1% osmium tetroxide, slices were washed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer pH 7.2. The slices were dehydrated through a series of ethanol solutions, infiltrated with epoxy resins and flat embedded. Slices with the lateral ventricle and the SVZ were trimmed and mounted on blocks and sectioned with an ultramicrotome. Ultrathin sections were counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and analysed with a Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope. Neurospheres were settled down by gravity and fixed with 1.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PB. The following postfixation and staining procedures for neurospheres were same as those for the SVZ tissues.

Neurosphere Formation Assay, in vitro Differentiation, and Cryosection

Neurosphere formation assay was performed as previously described 52. In brief, the SVZ tissues were isolated under dissection microscope and cut into ~1 mm3 cubes. They were digested in 0.2% Trypsin to obtain single cell suspension. The cells were cultured in neural basal media supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen, CA), 10 ng/ml bFGF and 20 ng/ml EGF (Invitrogen, CA) in Ultra-Low Attachment dishes (Corning, MA). Neurospheres with diameter larger than 50 μm were counted 7–9 days after culturing. For their passage, primary neurospheres were collected by centrifugation, and then incubated in 0.2% Trypsin at 37°C for 10 min with ~50 times pipetting. After addition of trypsin inhibitor supplemented with DNase I (Worthington, NJ) to stop digestion, dispersed cells were collected by centrifugation at 400g for 10 minutes, counted, and then cultured for the secondary neurospheres formation and quantified as described above. In some experiments, the dispersed cells from neurospheres were cultured for differentiation in neural basal media supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen, CA), 10 ng/ml bFGF and 5% (v/v) FBS in 48-well plates coated with 150 μg/ml poly-d-lysine (Biomedical Technologies, MA) and 20 μg/ml laminin (Invitrogen, CA) for another 7 days. Differentiated cells are stained with Tuj1 and GFAP for lineage analysis. In other experiments, neurospheres were fixed in 4% PFA for 30 min and then washed twice in cold PBS for 10 min. Fixed neurospheres were consecutively transferred to 20% and 30% sucrose to settle down overnight. They were embedded in O.C.T. (Sakura, CA), cryosectioned to get 10 μm slices (3050 Cryostat, Leica, Germany) and the slices were kept at −80°C before used for IF.

In some experiments, primary astrocytes were isolated from P0 Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice and cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS for 10 days. They were then re-plated into 0.4 mm pore size transwell membrane inserts (Costar) for 7 days. The cultured astrocytes were then rinsed, fed with neurosphere growth media, and the transwells containing the cells were placed above freshly plated embryonic NSCs isolated from E17.5 embryos. The cultures were fed with fresh neurosphere growth media every four days. The number of neurosphere was determined 10 days after co-culture as described above.

BrdU Incorporation Assay and TUNEL Assay

For in vitro experiments, BrdU was added to the neurosphere culture medium 2 hr before cell harvest at a final concentration of 10 μM. For in vivo studies, BrdU was administrated intra-peritoneally (I.P.) at 100 μg/gram for 3 times with 2 hr interval. Mice were either euthanized 2 hr after the last injection (short term incorporation) or 3 weeks later (long term retention), and tissues were processed as described above. For BrdU detection, the samples were treated with 2M HCL at room temperature for 20 min to denature the nucleotides and then neutralized with 0.1 M sodium borate at room temperature for another 20 min. After 3 washes in PBS (5 min each), slides were incubated with mouse anti-BrdU antibody and secondary antibodies as described in immunefluorescent staining. Nuclei were stained with DAPI and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, CA). For IF and detection of BrdU in the same tissue, IF was carried out first and samples were post-fixed with 4% PFA at room temperature for 20 min before nucleotides denaturing with HCL. Histological examination and digital photography were carried out as described above.

Apoptotic cells were detected by TUNEL method according to the protocol provided by the manufacture within the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit-TMR Red (Roche, Germany).

DHE Administration

Mice were injected I.P. with DHE prepared as follows. DHE powder was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to create a DHE stock solution (10 mg/ml). The DHE injectate (27 mg/kg) was produced by adding DHE stock solution to PBS and maintained at 40°C. Mice were anesthetized 18 hr after DHE injection and were perfused with 4% PFA in PBS. Samples were postfixed in 4% PFA at 4°C for 1 week and transferred to 20%, 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C. Brains were then embedded in O.C.T. compound and frozen on dry ice. Cryosection of 10 μm thickness was performed in 3050 Cryostat machine (Leica, Germany) and sectioned samples were kept at −80°C before IF. For IF in DHE stained samples, IF was carried out as described above.

Chloroquine (CQ) and NAC Administration

To show autophagy defects in cKO mice, CQ was administrated I.P. into Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice from P7 for 7 consecutive days at the concentration of 50 mg/kg in sterile PBS to block LC3II degradation. For in vitro experiments, NAC was added daily to the culture medium of neurospheres at a final concentration of 50 μM. For in vivo administration of NAC, freshly prepared NAC (10 mg/ml in PBS at pH.7.4) was subcutaneously injected into Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at a dose of 67 mg/kg once a day from P7 to P28. After 21 days NAC treatment, mice were injected DHE as described above. In some experiments, brains from NAC treated mice were split into halves at the end of treatment. One hemisphere was used for in vitro neurosphere assay and the other for IF and DHE staining. In other experiments, NAC treated mice were labeled first with BrdU for long term BrdU retention at P7 before the injection of NAC.

RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real Time PCR (Q-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from neurosphere using TRIzol reagent (Ambion, CA) and RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacture’s instruction. Revere transcription and Q-PCR using the SYBR Green PCR Core reagents system (Qiagen, Germany) were carried out as described previously 18. The primers for mouse PAX6, STAT3, p53, Notch1, Hes1, Hes5, Hey1 (sequences will be sent upon request), p21, PUMA, Fas (sequences as described previously 45) and internal control (sequence as described previously 18) were obtained from Fischer Scientific (Fischer Scientific, PA).

Protein Extraction, SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

The cortices were collected from embryos of Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice at E17.5. The SVZ tissues from Ctrl and FIP200hGFAP cKO mice were micro-dissected from 300-μm-thick coronal sections of P14 and P28 brains, and used for protein extraction by homogenization in modified radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 0.2% SDS, 1 mm sodium EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitors (5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). In other experiments, cells from neurospheres were obtained by centrifugation and dissolved with the same lysis buffer. After removing tissue and cell debris by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, protein concentration was determined using Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. The lysates were boiled for 5 min in 1×SDS sample buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 12.5% glycerol, 1% SDS, 0.01% bromphenol blue) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol. They were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using various antibodies, as described previously18,24.

Statistical analysis

Lengths, areas and the number of cells from comparable sections were quantified using the Image J software package. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. No data points were excluded in the analysis. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-tailed Student’s t-test, with p<0.05 as indicative of statistical significance using Graph Pad Prism (Version 4.0). Sample sizes were determined post-hoc based on sample sizes used in previous similar studies (e.g. ref 13 and 48)”. The number of animals used for quantification was indicated in the figure legends. Most of the experiments were successfully repeated at least three times and all at least two times.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Junying Yuan of Harvard Medical School for Spautin-1. We thank our lab colleagues for their discussions, help throughout the project, and helpful comments of the manuscript. This research was supported by NIH grant GM052890 to J.-L. Guan.

Footnotes

Contributions

C.W. conducted the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; C.-C. L. generated some mouse lines; Z.C.B. performed some study; Y. Z. analyzed the data; J.-L.G. conceived and supervised the study, analyzed the data and co-wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Doetsch F, Caille I, Lim DA, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:703–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kriegstein A, Alvarez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:149–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gage FH. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science. 2000;287:1433–8. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imayoshi I, et al. Roles of continuous neurogenesis in the structural and functional integrity of the adult forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1153–61. doi: 10.1038/nn.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell. 2008;132:645–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ueda H, Abbi S, Zheng C, Guan JL. Suppression of Pyk2 Kinase and Cellular Activities by FIP200. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:423–430. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hara T, et al. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: Renovation of Cells and Tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu F, et al. FIP200 is required for the cell-autonomous maintenance of fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortensen M, et al. The autophagy protein Atg7 is essential for hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. J Exp Med. 2011;208:455–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Belle JE, et al. Proliferative neural stem cells have high endogenous ROS levels that regulate self-renewal and neurogenesis in a PI3K/Akt-dependant manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gan B, et al. Role of FIP200 in cardiac and liver development and its regulation of TNFalpha and TSC-mTOR signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:121–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Y, et al. Early inactivation of p53 tumor suppressor gene cooperating with NF1 loss induces malignant astrocytoma. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizushima N. Methods for monitoring autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quick KL, Dugan LL. Superoxide stress identifies neurons at risk in a model of ataxia-telangiectasia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:627–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei H, et al. Suppression of autophagy by FIP200 deletion inhibits mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1510–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.2051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito K, et al. Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:446–51. doi: 10.1038/nm1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noble M, Mayer-Proschel M, Proschel C. Redox regulation of precursor cell function: insights and paradoxes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1456–67. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prozorovski T, et al. Sirt1 contributes critically to the redox-dependent fate of neural progenitors. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:385–94. doi: 10.1038/ncb1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tothova Z, et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128:325–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merkle FT, Tramontin AD, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Radial glia give rise to adult neural stem cells in the subventricular zone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17528–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407893101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang CC, Wang C, Peng X, Gan B, Guan JL. Neural-specific deletion of FIP200 leads to cerebellar degeneration caused by increased neuronal death and axon degeneration. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3499–509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hara T, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komatsu M, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vazquez A, Bond EE, Levine AJ, Bond GL. The genetics of the p53 pathway, apoptosis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:979–87. doi: 10.1038/nrd2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assaily W, et al. ROS-mediated p53 induction of Lpin1 regulates fatty acid oxidation in response to nutritional stress. Mol Cell. 2011;44:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lane D, Levine A. p53 Research: the past thirty years and the next thirty years. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000893. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louvi A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch signalling in vertebrate neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:93–102. doi: 10.1038/nrn1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross RE, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins promote astroglial lineage commitment by mammalian subventricular zone progenitor cells. Neuron. 1996;17:595–606. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hack MA, et al. Neuronal fate determinants of adult olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:865–72. doi: 10.1038/nn1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heins N, et al. Glial cells generate neurons: the role of the transcription factor Pax6. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:308–15. doi: 10.1038/nn828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuda S, et al. Potentiation of astrogliogenesis by STAT3-mediated activation of bone morphogenetic protein-Smad signaling in neural stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4931–7. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02435-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, et al. Beclin1 controls the levels of p53 by regulating the deubiquitination activity of USP10 and USP13. Cell. 2011;147:223–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chuikov S, Levi BP, Smith ML, Morrison SJ. Prdm16 promotes stem cell maintenance in multiple tissues, partly by regulating oxidative stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:999–1006. doi: 10.1038/ncb2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paik JH, et al. FoxOs cooperatively regulate diverse pathways governing neural stem cell homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:540–53. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renault VM, et al. FoxO3 regulates neural stem cell homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:527–39. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y, et al. Cytosolic FoxO1 is essential for the induction of autophagy and tumour suppressor activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:665–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mammucari C, et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 2007;6:458–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazumdar J, et al. O2 regulates stem cells through Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1007–13. doi: 10.1038/ncb2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madhavan L, Ourednik V, Ourednik J. Increased “vigilance” of antioxidant mechanisms in neural stem cells potentiates their capability to resist oxidative stress. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2110–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kippin TE, Martens DJ, van der Kooy D. p21 loss compromises the relative quiescence of forebrain stem cell proliferation leading to exhaustion of their proliferation capacity. Genes Dev. 2005;19:756–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.1272305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu D, et al. Puma is required for p53-induced depletion of adult stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:993–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meletis K, et al. p53 suppresses the self-renewal of adult neural stem cells. Development. 2006;133:363–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.02208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gil-Perotin S, et al. Loss of p53 induces changes in the behavior of subventricular zone cells: implication for the genesis of glial tumors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1107–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3970-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, et al. Expression of mutant p53 proteins implicates a lineage relationship between neural stem cells and malignant astrocytic glioma in a murine model. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:514–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh R, et al. Autophagy regulates adipose mass and differentiation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3329–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI39228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, et al. Adipose-specific deletion of autophagy-related gene 7 (atg7) in mice reveals a role in adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19860–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906048106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei H, Gan B, Wu X, Guan JL. Inactivation of FIP200 Leads to Inflammatory Skin Disorder, but Not Tumorigenesis, in Conditional Knock-out Mouse Models. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6004–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806375200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.