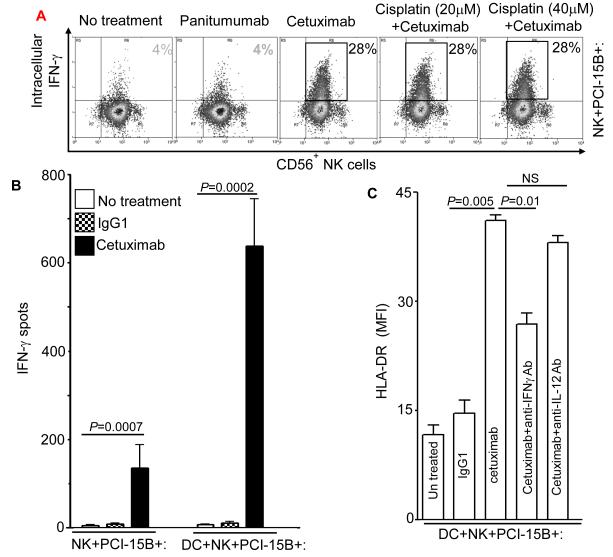

Figure 4.

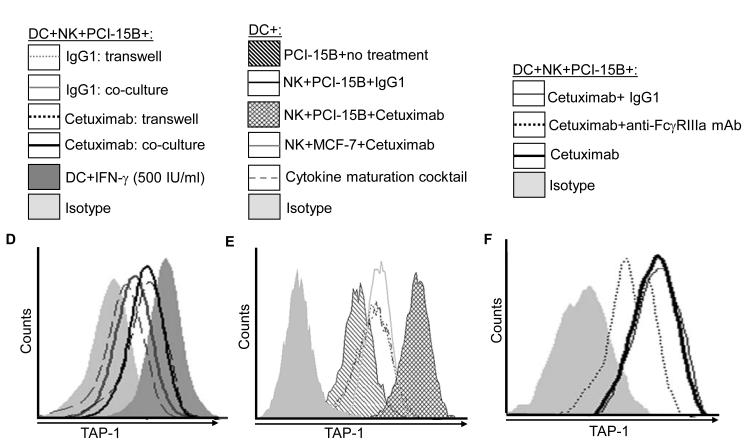

Enhancement by cetuximab of IFN-γ secretion by NK cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of intracellular IFN-γ in CD56+ NK cells, which were co-cultured with PCI-15B (1:1 ratio) with no treatment or with panitumumab or cetuximab (each 10μg/ml, 12h) in the presence or absence of cisplatin (20μm, 40μM). Representative figure of two independent experiments are shown. (B) Enhancement by cetuximab of IFN-γ secretion by NK-DC cross-talk in the presence of PCI-15B. The level of IFN-γ in the co-culture of NK:PCI-15B (1:1 ratio) or DC:NK:PCI-15B (1:1:1 ratio) with no treatment or with IgG1 or cetuximab (each at 10μg/ml) was measured after 12h of incubation by ELISPOT assay. Cumulative data of two donors are shown. A two-tailed unpaired t-test was performed for statistical analysis. (C) Importance of IFN-γ released by cetuximab activated NK cells in the enhancement of DC maturation. Percentages of HLA-DR+ DC in DC preparations co-cultured with NK:PCI-15B (at 1:1:1 ratio) with no treatment or with IgG1 or cetuximab (each at 10μg/ml, 48h) were measured by flow cytometry. In parallel, anti-IFN-γ mAb or anti-IL-12p40/70 mAb (each at 10μg/ml) were added along with cetuximab to the co-culture of DC:NK:PCI-15B, and DC maturation markers (HLA-DR+) were analyzed. Data are representative of two experiments from different donors. Enhancement by cetuximab of TAP-1 upregulation by DC in the presence of NK cells. (D-F) Enhancement of DC maturation by soluble factor released from cetuximab-activated NK cells. (D) TAP-1 upregulation in DC co-cultured with cetuximab-activated NK cell is mediated by a soluble factor. Flow cytometric analysis of intracellular TAP-1 expression (and TAP-2 expression, data not shown) was performed for DC incubated with NK:PCI-15B (1:1:1 ratio) with IgG1 or cetuximab (each at 10μg/ml, 48h). DC were physically separated from NK:PCI-15B co-culture using a transwell micropore system. TAP-1 expression in DC was enhanced after co-culture with NK:PCI-15B with cetuximab in both contact dependent and transwell culture conditions. Isotype (gray filled histogram), IgG1 transwell (gray dotted line), IgG1 co-culture (gray line), cetuximab transwell (black dotted line), cetuximab co-culture (black line), IFN-γ (black filled histogram). Data are representative of two experiments from two different donors. (E) Enhancement by cetuximab of TAP-1 upregulation in DC in the presence of NK cells with EGFRhigh HNC cells (PCI-15B), but not with breast cancer cells (MCF-7). By flow cytometry, intracellular TAP-1 expression (and TAP-2 expression, data not shown) was measured in DC that were incubated with NK:PCI-15B (at 1:1:1 ratio) or NK:MCF-7 (1:1:1 ratio) with IgG1 or cetuximab (each at 10μg/ml, 48h). No upregulation of TAP-1 was detected in DC that was incubated with NK:MCF-7 breast cancer cell cells (1:1:1 ratio) in the presence of cetuximab (each at 10μg/ml, 48h). As a control, the level of TAP-1 was measured in DC matured with cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, PGE2 for 48h). (F) Enhancement by cetuximab of TAP-1 upregulation by DC in the presence of NK cells is FcγRIIIa-dependent. TAP-1 expression was measured in DC incubated with NK:PCI-15B (1:1:1 ratio) in the presence of IgG1 isotype or cetuximab (each at 10μg/ml, 48h). A blocking FcγRIIIa-specific mAb (3G8) or IgG1 isotype control were used to demonstrate dependence of the observed TAP-1 upregulation (in DC) on FcγR expressed by NK cells, but not FcγR expressed by DC. Isotype (filled histogram), cetuximab plus IgG1 (thin line), cetuximab plus anti-FcγRIIIa-specific mAb (dotted line), cetuximab (thick line).