Abstract

The pathological progression of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is sex dimorphic such that male HCM mice develop phenotypic indicators of cardiac disease well before female HCM mice. Here, we hypothesized that alterations in myofilament function underlies, in part, this sex dimorphism in HCM disease development. Firstly, 10–12 month female HCM (harboring a mutant [R403Q] myosin heavy chain) mice presented with proportionately larger hearts than male HCM mice. Next, we determined Ca2+-sensitive tension development in demembranated cardiac trabeculae excised from 10–12 month female and male HCM mice. Whereas HCM did not impact Ca2+-sensitive tension development in male trabeculae, female HCM trabeculae were more sensitive to Ca2+ than wild-type (WT) counterparts and both WT and HCM males. We hypothesized that the underlying cause of this sex difference in Ca2+-sensitive tension development was due to changes in Ca2+ handling and sarcomeric proteins, including expression of SR Ca2+ ATPase (2a) (SERCA2a), β-myosin heavy chain (β-MyHC) and post-translational modifications of myofilament proteins. Female HCM hearts showed an elevation of SERCA2a and β-MyHC protein whereas male HCM hearts showed a similar elevation of β-MyHC protein but a reduced level of cardiac troponin T (cTnT) phosphorylation. We also measured the distribution of cardiac troponin I (cTnI) phosphospecies using phosphate-affinity SDS–PAGE. The distribution of cTnI phosphospecies depended on sex and HCM. In conclusion, female and male HCM mice display sex dimorphic myofilament function that is accompanied by a sex- and HCM-dependent distribution of sarcomeric proteins and cTnI phosphospecies.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, SR Ca2+ ATPase (2a) (SERCA2a), cTnI, Site-specific phosphorylation, Phosphate-affinity SDS–PAGE

Introduction

The identification that familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 has a genetic and molecular basis has prompted many investigations into the precise functional impairment in the sarcomere as it relates to the clinical manifestation [1–4]. As the first identified mutation genetically linked to HCM, the myosin 403 (R403Q) mutation typifies this approach. The R403Q model has significantly contributed to our understanding of HCM largely because this particular murine model of human HCM possesses multiple phenotypic similarities with their human counterparts including, (1) histologic and physiological characteristics, (2) course of disease progression, (3) pathological spectrum of disease phenotype, and (4) phenotypic differences between the sexes [5,6]. The R403Q mutation resides in the actin-binding domain and previous studies examining how the R403Q mutation impacts protein kinetics give inconsistent results such as either reduced [7] or enhanced [8] actin filament velocity and either reduced [9] or enhanced [10] actin-activated ATPase. On the other hand, myosin isolated from mouse hearts with the R403Q mutation consistently demonstrates increased actin velocity, actin-activated ATPase, and shorter crossbridge time-on measured by laser trap [8,10,11].

Yet, the role that Ca2+-sensitive tension development as an index of cardiac contractility plays in the progression of HCM is unclear. Studies consistently show that Ca2+-sensitive tension development of cardiac fibers is not different between young (6–20 weeks) WT and R403Q hearts [11–13] even though previous studies show that intact hearts from male mice expressing the R403Q mutation show greater contractility compared to controls [14,15]. The suggestion is that inherent myofilament tension development is not altered by the R403Q mutation and R403Q HCM disease progression is a complex integration of myofilament function, crossbridge kinetics, and cellular signaling.

Another confounding observation with the R403Q mutation is that R403Q HCM mice display sex dimorphisms despite similar expression levels of the mutation [5,6,16]. Male HCM mice develop progressive left-ventricular dilation and impaired cardiac function whereas female counterparts show increasing hypertrophy without dilation and maintain adequate ventricular function well beyond that of males. Some of the cellular and molecular mechanisms behind the sex differences in the R403Q mice include a number of pathologic indicators such as fibrosis, induction of β-myosin heavy chain, inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β, and activation of pro-apoptotic pathways in males but not females [5,16,17].

In a recent report identifying research priorities for HCM [18], there is a clear consensus that HCM mutations initiate pathological phenotypes by activating specific signaling pathways, some of which have already been studied using the R403Q mice [5,6,16,17,19]. However, the impact of post-translational modification of myofilament proteins in R403Q hearts as it relates to HCM disease progression and sex dimorphisms has not been adequately studied and may provide unique insight as to differences between the sexes. Post-translational modifications of myofilament proteins and the subsequent impact on myofilament function such as Ca2+-dependent tension development (Ca2+-sensitivity) becomes a key mechanism of short- and long-term remodeling within the cardiac cell [20,21]. However, several studies that have investigated phosphorylation status in diseased hearts do not present universal findings; some report a significant reduction in basal cardiac troponin I (cTnI) phosphorylation at PKA sites (Ser23/24) in human heart failure [22,23] whereas others show increased cTnI phosphorylation [24].

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that the sex dimorphic progression of HCM was, in part, due to underlying differences in Ca2+-sensitive tension development and a differential pattern of post-translational modifications. To do this, hearts of female and male mice harboring an HCM (R403Q) mutation at 10–12 months of age, where males exhibit established HCM disease [5,6], were assessed for Ca2+-sensitive tension development, hypertrophic markers, and post-translational changes in myofilament proteins. Here, we report that male and female HCM hearts display a unique pattern of Ca2+-sensitivity and myofilament protein phosphorylation.

Material and methods

Animal models

The experimental murine model has been detailed previously and consisted of male and female mice heterozygous for the mutant α-myosin transgene [5]. Wild-type (WT) littermates were used as controls for the HCM mice. All experiments were performed using protocols that adhered to guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arizona and to 2012 NIH guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals.

Skinned cardiac trabeculae for calcium-sensitive force measurement

Wild-Type and HCM male and female mice (10–12 months of age) were anesthetized with inhaled anesthesia (isoflurane) and the hearts were rapidly excised and retrogradely perfused with a modified Krebs–Henseleit (K–H) solution (NaCl 118.5 mmol/L, KCl 5 mmol/L, MgSO4 1.2 mmol/L, NaH2PO4 2 mmol/L, D-(+)-glucose 10 mmol/L, NaHCO3 25 mmol/L, CaCl2 0.2 mmol/L) [25]. 2,3-Butanedione monoxime (20 mmol/L) was used to inhibit contraction presumably through the energetic stabilization of the unattached state of the myosin molecule [26]. Thin, uniform, and unbranched trabeculae were dissected from the RV free wall and transferred to an ice-cold standard relaxing solution (EGTA = 10 m-mol/L; ionic strength = 180 mmol/L) containing 1% Triton X-100 for a minimum of 2 h to allow solubilization of all membranous structures. Following excision of cardiac trabeculae, atria were removed and right and left ventricles separated. All tissue was then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for sample analysis at a later time.

Ca2+-sensitivity of force development

The experimental apparatus for mechanical measurements of skinned cardiac trabeculae was similar to that described previously [27,28]. The fiber was attached to the apparatus via aluminum T-clips to stainless steel hooks that extended from a high-speed servomotor and a modified strain gage force transducer (Permeabilized Fiber Test System, Aurora Scientific), both of which were attached to X–Y–Z manipulators mounted on a movable microscope stage. This allowed the suspended muscle to be lowered into a muscle trough that was temperature controlled (15 ± 0.1 °C). Sarcomere length was measured in a central segment of the muscle preparation by video micrometry and set at 2.2 μm for all experiments.

The Ca2+-sensitivity of force as a function of sarcomere length was determined as described previously [28] with slight modifications. Prior to activation, the relaxing solution in the muscle bath was exchanged with a pre-activating solution (Table 1). Following the determination of force, a quick release prior to fiber relaxation was used to identify the zero force level. The step size of the quick release was the minimum step that allowed accurate determination of both steady-state tension and the zero force level. Subsequently, the amount of active force generated at each [Ca2+] was calculated as the difference between total force and relaxed, passive force that was assessed by slackening the fiber while it was in the relaxed state. To determine any decline in force-generating capability, the fiber was maximally activated at the beginning and at the end of the protocol. If the fibers did not maintain 90% of initial maximal force then the fiber data was discarded.

Table 1.

Ca-EGTA is made by mixing equimolar amounts of CaCl2 and EGTA. In addition, all solutions contained the following (in mmol/L): 10 phosphocreatine, 100 N,N-bis[2-hydroxyethyl]-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (BES), 0.1 leupeptin, 0.1 phenylmethyl-sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 dithiothreitol (DTT), and 4 U/ml creatine phosphokinase. Free Mg2+ and Mg-ATP concentration was 1 and 5 mmol/L, respectively. Relaxing and activating solutions was mixed to obtain the desired range of free [Ca2+] assuming an apparent stability constant of the Ca2+-EGTA complex of 106.39 at 15 °C. The preactivating solution with low Ca2+ buffering capacity containing 1,6-diaminohex-ane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (HDTA) was used prior to the activating solution.

| Solution | MgCl2 | Na2ATP | EGTA | HDTA | Ca-EGTA | KProp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relaxing | 6.41 | 5.95 | 10 | 50.25 | ||

| Preactivating | 6.25 | 5.95 | 0.25 | 9.75 | 50.51 | |

| Activating | 6.20 | 6.08 | 10 | 29.98 |

Because of the experimental criteria, approximately 90% of the muscle preparations were discarded. Force in submaximally activating solutions was expressed as a fraction (Frel) of the maximum force (F0) at the same sarcomere length. The F0 value used to normalize submaximal force was obtained by linear interpolation between successive maximal activations. Each individual Ca2+-force relationship was fit to a modified Hill equation where , Frel = relative force, EC50 = [Ca2+] at which force is half-maximal, n = slope of the Ca2+-force relationship (Hill coefficient). The differences among EC50 for each group were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test to compare differences between mean values. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M.

Solutions for Ca2+-force experiments

The ionic strength of the solutions was kept at 180 mmol/L by adding the appropriate amount of potassium propionate (Table 1). Ca-EGTA was made by mixing equimolar amounts of CaCl2 and EGTA. In addition, all solutions contained the following (mM): phosphocreatine 10, N, N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (BES) 100, leupeptin 0.1, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) 0.1, dithiothreitol (DTT) 1, and 4 μ/ml creatine phosphokinase. The free Mg2+ and Mg-ATP concentration were calculated at 1 and 5 mmol/L, respectively. Relaxing and activating solutions were appropriately mixed to obtain a range of free [Ca2+] (temperature kept constant at 15 °C). The pH was adjusted to 7.0 at 15.0 °C with KOH.

Real time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the left ventricles of WT and HCM mouse hearts using the High Pure miRNA Isolation kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total cDNA was generated with NCode™ miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). Real time PCR was done via Universal ProbeLibrary Assay (Roche) using LightCycler 480 system (Roche). Primers for Universal ProbeLibrary Assay were designed using the probeFinder software. Primers for the HCM-R403Q transgene (normalized to GAPDH) were as follows: rat α-MyHC forward primer: ccaggtcaacaagctgcgg; reverse primer: tgtggtgtaaatagcaaag. LightCycler 480 probe master mix was used. Samples were prepared according to manufacturer’s protocol and run in duplicates on a 96-well plate. B-actin was used as the internal control of mRNA for Universal ProbeLibrary Assay.

Mouse cardiac samples for SDS–PAGE

A small portion of left ventricular tissue was broken off (5–10 mg) using a ceramic mortar and pestle cooled in liquid nitrogen. The cardiac tissue was weighed and then homogenized in sample buffer (50% urea, 25% glycerol, 34 mM DTT, 0.25 mM PMSF, 0.01 mM TPCK, 0.01 mM TLCK, 0.5 mM NaP2O7, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail [2.6 mM AEBSF, 2 μM aprotinin, 0.1 mM bestatin, 35 μME-64, 50 μMleupeptin, 37.5 μMpepstatin]) 5:1 sample buffer volume (μL) to cardiac tissue mass (mg). Post homogenization, samples were centrifuged for 30 s at maximum speed and sample buffer was added to bring the final volume (μL) to 40× the cardiac tissue mass (mg). Samples were incubated at 100 °C for 5 min, then aliquots were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Separation of cardiac myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms

Frozen heart samples were prepared as detailed above for SDS–PAGE to determine relative cardiac MyHC content as previously described [17]. The gels were silver stained and analyzed using a Umax PowerLook 1120 flatbed scanner with 1200 × 2400 dpi and 3.7 Dmax. To determine relative MyHC content, 6–7 dilutions of each sample were analyzed to stay in the linear densitometric range. From the linear relationships determined for each MyHC isoform, the relative MyHC content of each isoform were extrapolated. Soleus (containing predominately type I/(β-MyHC and type IIa MyHC) or neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (containing both α̃ and β-MyHC) were used as standards.

Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein staining

SDS–PAGE was used to separate out myofilament proteins and to measure phosphorylation status as detailed previously [29]. Briefly, the composition of SDS–PAGE gels were as follows, stacking gel: 5% acrylamide (29:1 acrylamide: bis-acrylamide), 0.1% SDS, 0.1% APS, 0.1% TEMED, 0.125 MTris pH 6.8; resolving gel: 12% acrylamide (29:1 acrylamide: bis-acrylamide), 0.1% SDS, 0.1% APS, 0.06% TEMED, 0.375 M Tris pH 8.8. Approximately, 10–12 μg of total protein was loaded into each lane. Gels were run using the Criterion system in ice cold running buffer (2.5 mM Tris, 19 mM glycine, 0.35 mM SDS) and at constant current (30–40 mA per gel).

Gels were then fixed (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid) with gentle agitation at room temperature for 30 min followed by 3 10-min washes in ultrapure water. Gels were incubated in Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein gel stain with gentle agitation for 90 min at room temperature, in the dark. All following steps were carried out in the dark. Gels were incubated 2× in destain solution (20% acetonitrile, 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0) with gentle agitation at room temperature for 30 min, followed by 2 × 5-min washes in ultrapure water. Gels were imaged using GE Typhoon Biomolecular imager. Gels were then stained with Coomassie (see Coomassie Brilliant Blue Staining) for total protein. Phosphorylated protein optical densities were quantified using LabImage 1D software and normalized to their respective Coomassie stained total protein bands or to overall total protein.

Phosphate-affinity (Phos-tag™) SDS–PAGE

Hand-cast phosphate-affinity SDS–PAGE (SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™) gel compositions were as follows: 5% acrylamide (stacking gel; 29:1 acrylamide: bis-acrylamide), 0.1% SDS, 0.1% APS, 0.1% TEMED, 0.125 M Tris pH 6.8; 11% acrylamide (resolving gel; 29:1 acrylamide: bis-acrylamide), 0.1% SDS, 0.15% APS, 0.3% TEMED, 0.4 M Tris pH 8.8, 0.2 mM MnCl2, 0.1 mM Mn-Phos-tag™-acrylamide. Approximately, 10–12 μg of total protein was loaded onto each lane. Gels were run using the Criterion system at 4 °C, on ice, in cold running buffer (2.5 mM Tris, 19 mM glycine, 0.35 mM SDS). Proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes using the Trans-Blot system (BioRad). Membranes were probed using the following antibodies: total cTnI (AbCam; 1:10,000); cTnI-ser23/24 (Cell Signaling; 1:1000); cTnI-ser150 (Proteintech Group, custom antigen; 1:1000).

Cardiac tissue samples prepared from transgenic mice harboring a mutant cTnI protein lacking phosphorylation sites ser23/24, ser43/35 and thr144 (mutated to alanine) [30] and cardiac myocytes (prepared as described below) treated with protein phosphatase (PP1 α-isoform; 1.5 U/μL) or protein kinase A (PKA catalytic subunit; 1 U/μL) treated cardiomyocytes were used as standards for the un-phosphorylated (0P), mono-phosphorylated (1P), and bis-phosphorylated (2P) species of cTnI. Each phosphospecies band was then quantified using LabImage 1D software and normalized to protein optical densities for total cTnI. Each SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ was run in triplicate. Then, triplicate samples (n = 4 for each experimental group) were averaged to obtain 1 value for each of the four samples.

All immunoblot analysis was performed from the semi-quantitation of individual blots and was not compared across blots according to accepted guidelines. All immunoblot images of a given target were cropped from the same blot in order to conserve figure space and redundancy.

Data and statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. A 2-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test or a student’s t test was performed to compare differences between mean values. Because we cannot perform paired analysis to determine the extent of cardiac growth, cardiac hypertrophy was represented as the relative change to respective WT controls. To do this, the percent change in cardiac mass with was determined by comparing the cardiac mass of HCM mice to the mean cardiac mass of the respective WT group as previously described [17]. The difference in cardiac mass was then expressed as a percent change from WT animals for each respective animal. p Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Animal morphometry

At 10–12 months of age, each animal was analyzed for body and cardiac mass following sacrifice. The results of these findings are summarized in Table 2. HCM hearts of both sexes exhibited significant cardiac hypertrophy as evidenced by an increase in absolute ventricular weight (VW). This is consistent with previous data in 8–10 month HCM mice [16,31]. This significant cardiac hypertrophy in HCM mice was also evident when VW was normalized to tibial length (TL). To determine if the impact of the HCM transgene was sex dimorphic, we calculated the percent increase in cardiac mass (percent cardiac hypertrophy) from WT controls. Compared to respective WT controls, the hypertrophic response in female HCM mice was nearly 3-fold greater compared to male HCM mice (19.3 ± 2.9% vs. 6.9 ± 3.1%, p < 0.01). To determine whether this increase in overall heart weight was due to myocyte hypertrophy and not myocyte proliferation, we measured in cardiac cell size in F-WT and F-HCM hearts. We found a similar increase in myocyte cell size (17.5 ± 3.3%) in F-HCM compared to F-WT myocytes.

Table 2.

Summary of morphometric data from 10 to 12 month HCM and WT male and female mice. VW/BW was determined by dividing ventricular mass (in mg) by body weight (in g). Likewise VW/TL was determined by dividing ventricular mass (in mg) by tibial length (in mm) (*p < 0.05 from values obtained in WT counterparts). A 2-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test or a student’s t test was performed to compare differences between mean values.

| Group | Body weight (g) | Ventricular weight (mg) | VW/BW (mg/g) | VW/TL (mg/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | ||||

| WT (n = 10) | 33.6 ± 2 | 99.9 ± 3.0 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 |

| HCM (n = 15) | 37.0 ± 1* | 119.1 ± 2.9* | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 0.2* |

| Males | ||||

| WT (n = 9) | 33.9 ± 1 | 127.3 ± 5.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.2 |

| HCM (n = 14) | 35.9 ± 1* | 138.2 ± 4.2* | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 7.3 ± 0.2* |

Calcium (Ca2+) sensitivity of myofilament tension development

An important determinant of cardiac contractility in the whole heart is the underlying sensitivity of the myofilaments to calcium (Ca2+). A recent study reports that the R403Q mutation does not impact Ca2+-sensitive tension development in demembranated cardiac fibers when compared to controls from either sex in 10–20-week old mice, when R403Q mice exhibit no observable HCM pathology [6,11,12]. Accordingly, we wished to determine if the sex-dimorphism in cardiac hypertrophy was accompanied by altered Ca2+-sensitivity of tension development in HCM mice with established HCM pathology. Therefore, we measured Ca2+-sensitive tension development in demembranated cardiac trabeculae from 10–12 month WT and R403Q male and female mice. Fig. 1 shows the relationship between steady-state force development and free [Ca2+] in skinned trabeculae from WT and R403Q male and female mice; the solid and dashed lines indicate the best fit of the Ca2+-force coordinates to a modified Hill equation whose parameters are summarized in Table 3. We demonstrated that HCM did not affect Ca2+-sensitive tension development in demembranated cardiac trabeculae from males (Fig. 1A). Cardiac trabeculae from F-HCM mice were significantly more sensitive to Ca2+ than WT controls (Fig. 1B). Moreover, while Ca2+-sensitivity was greater in M-WT and M-HCM trabeculae compared to F-WT, they were less sensitive to Ca2+ than cardiac trabeculae from F-HCM hearts. There were no differences in maximal tension generation between experimental groups as previously reported [12].

Fig. 1.

Ca2+-sensitive tension development in demembranated cardiac trabeculae from WT and HCM male and female mice. A: Ca2+-sensitive tension development in demembranated cardiac trabeculae from female WT (F-WT; closed triangles) and HCM (F-HCM; open triangles) hearts. B: Ca2+-sensitive tension development in demembranated cardiac trabeculae from male WT (M-WT; closed circles) and HCM (M-HCM; open circles) hearts. Sarcomere length was set to 2.2 μm and the data were normalized to Ca2+-saturated (maximum) tension. F-WT: female wild-type mice; F-HCM: female HCM mice; M-WT: male wild-type mice. M-HCM: male HCM mice.

Table 3.

Average Hill fit parameters of the Ca2+-Force relationships obtained from WT and R403Q male and female hearts at a sarcomere length of 2.2 μm. Hill equation: , Frel = relative force, EC50 = [Ca2+] at which force is half-maximal, n = slope of the Ca2+-force relationship (Hill coefficient).

| Group | EC50 (μm) | Hill Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| Female | ||

| WT (n = 4) | 1.67 ± 0.40* | 2.75 ± 0.28 |

| HCM (n = 6) | 0.80 ± 0.10† | 2.84 ± 0.27 |

| Male | ||

| WT (n = 6) | 1.01 ± 0.08 | 3.2 ± 0.21 |

| HCM (n = 15) | 1.07 ± 0.07 | 2.78 ± 0.10 |

p < 0.05 from measured EC50 obtained from Males (WT and HCM) and Female (HCM);

p < 0.01 from measured EC50 obtained from Males (WT and HCM) and Female (WT).

A 2-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test or a student’s t test was performed to compare differences between mean values.

Expression of β-myosin heavy chain

Although rodent myocardium predominantly expresses the α isoform of the myosin heavy chain (MyHC) gene, increased expression of β-MyHC occurs in response to pathological cardiac stimuli [32,33]. Expression of β-MyHC can negatively impact cardiac performance [34] by decreasing power output [35] or increasing the Ca2+-sensitivity of tension development [36,37]. More specific to this study, expression of β-MyHC impacts myofilament function in HCM mice [37]. Therefore, we wished to determine whether a shift in MyHC protein content underlies the differences in Ca2+-sensitivite tension development. First, we determined whether F-HCM and M-HCM hearts expressed similar levels of the HCM transgene. Using RT-PCR, we found the same level of transgene expression in F-HCM compared to M-HCM hearts (Fig. 2A). Next, a significantly higher level of β-MyHC message in M-HCM was measured compared to their WT controls and to both female groups (Fig. 2B). F-HCM hearts showed elevated β-MyHC message expression compared to F-WT controls, albeit not significantly. Next, relative MyHC content was quantified by SDS–PAGE as previously described [17]. We confirmed the significant elevation of β-MyHC protein in M-HCM hearts [16,31] but also demonstrated that F-HCM hearts had significantly more β-MyHC relative to their WT controls (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the amount of relative β-MyHC was not different between F-HCM and M-HCM hearts.

Fig. 2.

Expression of HCM-transgene and β-MyHC in WT and HCM male and female mice. A: Using quantitative real-time PCR, bar graph summary of HCM transgene expression in F-HCM and M-HCM hearts. B: Box plot summary of relative levels of β-myosin heavy chain (MyHC) was determined. (*p < 0.05 from all other groups; n = 5–6 for each group.) C: β-MyHC protein expression using SDS–PAGE. A series of 6–7 increasing concentrations starting ranging 1–80-fold were used to calculate relative expression of each MyHC isoform. Top panel: three of the 6–7 concentrations illustrate clearly separated α-MyHC and β-MyHC that were silver-stained and quantified as detailed in the methods. Soleus expressing Type I (β) MyHC and Type IIa and neonatal rat myocytes expressing α-MyHC and β-MyHC (not shown) are used as a MyHC standards. A 2-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test or a student’s t test was performed to compare differences between mean values. (*p < 0.05 as indicated; n = 6–7 for each group.) F-WT: female wild-type mice; F-HCM: female HCM mice; M-WT: male wild-type mice. M-HCM: male HCM mice.

Expression of Ca2+ handling proteins

Although expression of the SR Ca2+-ATPase pump (2a) (SER-CA2a) is typically decreased in heart failure [38], its expression in HCM hearts depends on time of HCM presentation, HCM geno-type and sex [39]. Therefore, we hypothesized that HCM hearts would show a HCM and sex dimorphic pattern in the expression of SERCA2a and other Ca2+-handling proteins including phospholamban (PLB). SERCA2a expression by Western Blot analysis was highest in F-HCM hearts over all other experimental groups including F-WT counterparts (Fig. 3). Interestingly, SERCA2a levels were lowest in M-HCM hearts although not significantly less than the levels in M-WT. The elevation of SERCA2a expression in F-HCM hearts is accompanied by no significant change in PLB expression (a negative regulator of SERCA2a) among all groups studied. However, F-HCM hearts showed a significant increase in PLB phosphorylation at Ser16/Thr17 compared to F-WT control mice, while no significant change was detected between either M-WT or M-HCM (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Expression of Ca2+ handling proteins in WT and HCM male and female mice. Top panel: Ca2+ handling proteins, SR Ca2+-ATPase (2a) (SERCA2a) and phospholamban (PLB), were assessed by immunoblot analysis. Bottom panel (left): Bar graph summary of SERCA2a levels in WT and HCM female (F-WT and F-HCM, respectively) and male (M-WT and M-HCM, respectively) hearts. Bottom panel (right): Bar graph summary of phospholamban phosphorylation at ser16/17 (PLBser16/17) levels in WT and HCM female (F-WT and F-HCM, respectively) and male (M-WT and M-HCM, respectively) hearts. A 2-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test or a student’s t test was performed to compare differences between mean values. (*p < 0.05 from all other groups; n = 4 for each group.) F-WT: female wild-type mice; F-HCM: female HCM mice; M-WT: male wild-type mice. M-HCM: male HCM mice.

Phosphorylation of sarcomeric myofilament proteins

A central mechanism by which the heart responds to both acute and chronic stimuli is through post-translation modifications of sarcomeric myofilament proteins [40]. Using SDS PAGE followed by Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein staining, we were able to identify and quantify phosphorylation levels of five myoflament proteins, cardiac troponin I (cTnI), cardiac troponin T (cTnT), cardiac tropomyosin (cTm), myosin light chain 2 (MLC2), and myosin binding protein C (MyBP-C) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Phosphorylation status of myofilament proteins. Left ventricular myocardial samples of 12-month-old WT and R403Q female and male mice were separated by SDS–PAGE. Top panel (left): Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein stain of SDS–PAGE used to determine relative phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I (cTnI), myosin binding protein C (MyBP-C), cardiac troponin T (cTnT), tropomyosin (Tm) and myosin light chain 2 (MLC-2). A non-phosphorylatable cTnI (Ala5 [30]) was used as a negative control. Top panel (right): Coomassie Brilliant Blue stain of SDS–PAGE used to normalize relative phosphoprotein stain. Bottom panel (left): Bar graph summary of total cTnI phosphorylation levels. Bottom panel (right): Bar graph summary of total cTnT phosphorylation levels. A 2-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test or a student’s t test was performed to compare differences between mean values. (*p < 0.05 from respective HCM hearts; #p < 0.05 from M-WT and M-HCM; n = 4 for each group.) cTnI: cardiac troponin I; cTnT: cardiac troponin T; cTm: tropomyosin; MLC2: myosin light chain 2; MyBP-C: myosin binding protein C. F-WT: female wild-type mice; F-HCM: female HCM mice; M-WT: male wild-type mice. M-HCM: male HCM mice.

Although we were unable to detect differences in the phosphorylation levels of cTnI in any of the groups, we did find a significant reduction of cTnT phosphorylation in F-HCM relative to F-WT hearts (Fig. 4). M-HCM hearts also had significantly lower levels of phosphorylated cTnT. Moreover, F-WT hearts showed higher cTnT phosphorylation levels than all other groups. Phosphorylation of cardiac tropomyosin (cTm), myosin light chain 2 (MLC2) and myosin binding protein C (MBP-C) were not significantly different among the groups studied.

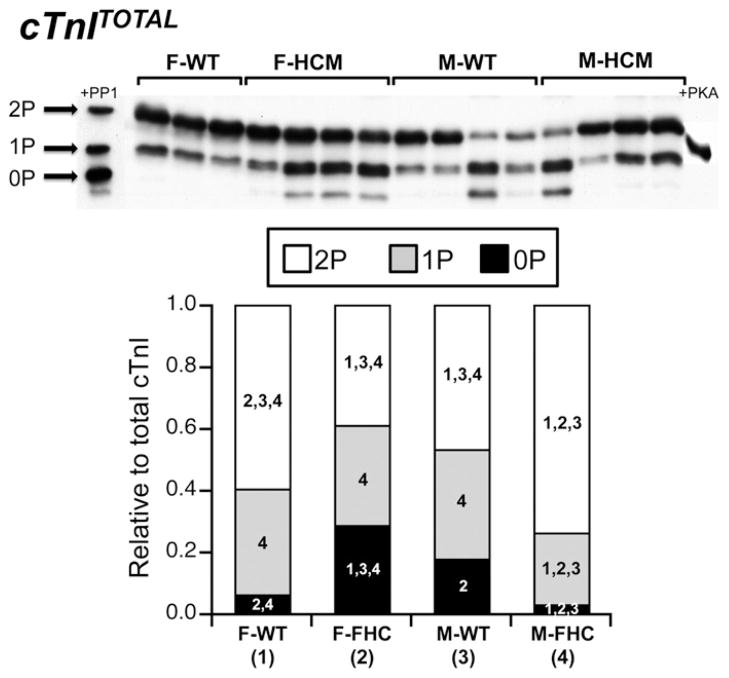

Phosphorylation of cTnI: P-cTnITOTAL

In the heart, cTnI represents the point of convergence at several target sites for multiple kinases including cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), and p-21 activated kinase [40]. Despite no sex or HCM dependent differences in total cTnI phosphorylation determined by Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein staining (Fig. 4), we wished to investigate whether sex or HCM resulted in differential site-specific phosphorylation and/or distribution of cTnI phospho-species. Using SDS–PAGE containing a phosphate-binding tag (Phos-tag™) followed by Western Blot analysis with a cTnI-specific antibody, we detected three distinct bands of cTnI corresponding to the un-, mono- and bis-phosphorylated (0P, 1P, and 2P, respectively) species of cTnI [41]. Cardiac myocytes treated with either protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) or protein kinase A (PKA) were used to identify each phosphospecies. Here, the relative distribution of cTnI phospho-species was dependent on both sex and presence of the HCM mutation (Fig. 4). The amount of 2P-cTnI was significantly different in all experimental groups studied with the order from greatest to least as follows: M-HCM > F-WT > M-HCM > F-HCM. Furthermore, M-HCM hearts contained significantly less 1P-cTnI compared to the other groups. F-HCM hearts exhibited the greatest level of 0P-cTnI followed by M-WT hearts. On the other hand, M-HCM hearts displayed a reduction in the amount of 0P-cTnI that was not different from M-HCM hearts but significantly less than F-HCM and M-WT hearts.

Phosphorylation of cTnI: P-cTnI-ser23/24

Stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors and subsequent activation of cAMP-protein kinase A (PKA) signaling axis is a key mechanism by which the heart dynamically regulates contractility in response to stress [40]. In addition, overstimulation of this path-way is suggested to play an important role during pathological cardiac remodeling [23,42]. Therefore, we examined site-specific phosphorylation of cTnI at the putative PKA sites, cTnI ser23/24 (P-cTnI-ser23/24) using SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ followed by Western Blot analysis using a phospho-specific antibody for P-cTnI-ser23/24. This method of analysis indicated the presence of 2 cTnI phospho-species corresponding to the 1P and 2P forms of cTnI (Fig. 5 and Supplemental data Fig. 1). Total phosphorylation at cTnI-ser23/24 was elevated in M-HCM mice over F-HCM and M-WT. Interestingly, F-WT demonstrated total P-cTnI-ser23/24 that was greater than F-HCM and M-WT but similar to M-HCM.

Fig. 5.

Phosphate affinity SDS–PAGE (SDS–PAGE Phos-tag™) for total cTnI (cTnITOTAL). Separation of cTnI into distinct phosphospecies (unphosphorylated [0P], mono-phosphorylated [1P], bis-phosphorylated [2P]) by phospho-affinity SDS–PAGE (SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™) followed by Western blot analysis with a total cTnI antibody (cTnITOTAL). Top panel: Representative SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ followed by Western blot illustrating three distinct bands corresponding to 0P, 1P, and 2P. Protein phosphatase 1-treated myocytes (+PP1) and protein kinase-treated (+PKA) were used to confirm each phosphospecies. Bottom panel: Stacked bar graph summary indicating the relative amounts of each phosphospecies for each experimental group. Each lane was normalized to the total protein determined from the Coomassie Brilliant Blue protein stain. Each experimental group was set to a standard of one and all phosphospecies were expressed as a relative ratio. The numerical value within each phosphospecies refers to statistical significance (p < 0.05) from the indicated group. A 2-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test or a student’s t test was performed to compare differences between mean values. Each numerical value corresponds to the matched experimental group as indicated. F-WT (1): female wild-type mice; FHCM (2): female HCM mice; M-WT (3): male wild-type mice and M-HCM (4): male HCM mice.

In addition to significant differences in total P-cTnI-ser23/24 phosphorylation between experimental groups, we detected sex and HCM-dependent differences in the distribution of cTnI-ser23/ 24 phospho-species (Fig. 6A). Comparing the amount of cTnI-ser23/24 that exists in the bis-phosphorylated (2P) form, F-WT hearts had significantly more 2P-cTnI-ser23/24 than F-HCM hearts whereas M-HCM hearts had significantly more 2P-cTnI-ser23/24 than M-WT hearts. Furthermore, this quantity of 2P-cTnI-ser23/24 in M-HCM hearts was more than F-HCM but not F-WT hearts. Overall, F-HCM hearts showed the highest levels of 1P-cTnI-ser23/ 24 that was significantly elevated over F-WT and M-HCM. M-HCM showed the least amount of 1P-cTnI-ser23/24 that was significantly lower than F-HCM and M-WT hearts.

Fig. 6.

Phosphate affinity SDS–PAGE (SDS–PAGE Phos-tag™) for phosphorylated cTnI at cTnISer23/24 (P-cTnI-ser23/24) and cTnISer150 (P-cTnI-ser150). Phosphateaffinity SDS–PAGE (SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™) followed by Western blot analysis with cTnI antibodies targeting Ser23/24 (P-cTnI-ser23/24) or Ser150 (P-cTnI-ser150) only when phosphorylated. A (top panel): Representative SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ followed by Western blot with a P-cTnI-ser23/24 antibody illustrating two distinct bands corresponding to 1P and 2P. Protein phosphatase 1-treated myocytes (+PP1) and protein kinase-treated (+PKA) were used to confirm each phosphospecies (Supplemental Data Fig. 1). Bottom panel: Stacked bar graph summary indicating the relative amounts of phosphospecies 1P and 2P for each experimental group. B (top panel): Representative SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ followed by Western blot with a P-cTnI-ser150 antibody illustrating three distinct bands corresponding to 0P, 1P, and 2P. Bottom panel: Stacked bar graph summary indicating the relative amounts of phosphospecies 0P, 1P and 2P for each experimental group. For each of the stacked bar graphs, the summed band densities were used as a measure of total cTnI phosphorylation at cTnI-ser23/24 or cTnI-ser150. Each lane was normalized to total P-cTnI-ser23/24/cTnI-ser150 of F-WT levels after adjustment for protein loading based on total cTnI. Each phosphospecies were expressed as a relative ratio of total P-cTnI-ser23/24/cTnI-ser150. The numerical value within each phosphospecies refers to statistical significance (p < 0.05) from the indicated group. A 2-way ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman Keuls post hoc test or a student’s t test was performed to compare differences between mean values. Each numerical value corresponds to the matched experimental group as indicated. F-WT (1): female wild-type mice; FHCM (2): female HCM mice; M-WT (3): male wild-type mice and M-HCM (4): male HCM mice.

Phosphorylation of cTnI: P-cTnI-ser150

Although cTnI can be phosphorylated at a number of residues, several recent studies have pointed out the significance of cTnI phosphorylation at ser150 (P-cTnI-ser150) and its impact on Ca2+-sensitivity of tension development [43–45]. Accordingly, we probed hearts using a phospho-specific antibody for phospho-cTnI-ser150 [46] following SDS–PAGE containing Phos-tag™. We are able to detect phosphorylation at P-cTnI-ser150 in the 0P, 1P and 2P bands indicating the existence of cTnI-ser150 in at least three states of cTnI phosphorylation (Fig. 6B). Although total phosphorylation at cTnI-ser150 was similar among the groups studied, there was a significant difference in the distribution of phospho-species that contained P-cTnI-ser150. In this study, we unexpectedly detected a positive 0P-cTnI-ser150 that was elevated in F-HCM hearts compared to all other groups, despite evidence that the antibody targeting P-cTnI-ser150 does not detect cTnI in the unphosphorylated state (Supplemental data Fig. 2 and see [47]).

Discussion

The view that gender acts as an important determinant of HCM clinical outcome is becoming increasingly accepted [48]. In this study, three critical findings support this clinical fact but also outline the difficulty with identifying a key cellular and/or molecular mechanism underlying these sex dimorphisms. First, by 10–12 months of age, HCM females develop proportionately larger hearts than HCM male counterparts. Second, in cardiac trabeculae from these same hearts, HCM females display alterations in the Ca2+-sensitivity of tension development over their female WT controls whereas HCM males do not. Third, the pattern of post-translational modifications depends on both sex and HCM genotype.

Although the increase in Ca2+-sensitivity may provide inotropic support at the myofilament level for HCM female hearts attenuating HCM progression unlike male counterparts, it becomes difficult to attribute changes in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity to the development of HCM. Alternatively, it is possible that the changes in Ca2+-sensitivity are purely an outcome of HCM disease progression. Because previous measurements show no HCM-dependent differences in Ca2+-sensitivity [12] and were taken at an early timepoint, HCM disease progression is most likely not the result of perturbations in Ca2+-sensitivity. Considering that the current study illustrates differences in Ca2+-sensitivity, we suggest that, as HCM disease progresses, alterations in Ca2+-sensitivity become part of an iterative feedback system with cellular signaling pathways to tune or modulate sarcomeric function to meet hemodynamic demand. In support of this contention, in a recent statement by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, it is now appreciated that HCM disease progression depends on activation of cellular signaling pathways that can modify the HCM phenotype, such as Ca2+-sensitivity [18].

Increased β-MyHC expression is a hallmark of pathological disease progression in the heart [5,33,49], and the pathological consequences of this isoform shift are beginning to emerge. Because HCM female hearts do not express elevated β-MyHC levels at earlier timepoints [5,16], these data, along with the increased SERCA2a expression and decreased PLB/SERCA2a in HCM female hearts compared to males [39], are consistent with a delayed onset of HCM disease progression in females.

Apart from the well established reduction in power output in hearts expressing β-MyHC [35], Ca2+-sensitivity of tension development is also increased [36,37]. This β-MyHC shift in female HCM hearts can partly underlie the increase in Ca2+-sensitivity but not in male HCM hearts. This latter finding is of particular interest considering that sarcomere dynamics in mice expressing an HCM cTnT transgene are impacted by MyHC expression [37]. In the current study, β-MyHC expression was similar in males and females pointing to an alternate cause of the sex-dimorphic myofilament phenotype, specifically, post-translational modifications. Incidentally, male HCM hearts display reduced cTnT phosphorylation potentially impacting the observed phenomenon.

The dynamic properties of cardiac myocytes are dramatically affected by post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation that targets myofilament proteins [50]. Phosphorylation of specific serine/threonine residues on cTnI is dynamically regulated by several kinases and phosphatases and has known effects on Ca2+-sensitivity [51], crossbridge cycling rate [52] and Ca2+ binding characteristics [53]. In addition, the impact that phosphorylation can have on sarcomere dynamics is altered by the presence of MyHC isoform and HCM mutations [37,53]. There are no documented studies addressing phosphorylation status of cTnI or sex-dimorphisms in cTnI phosphorylation in R403Q HCM mice.

Because there are no detectable differences in total cTnI phos-phorylation by Pro-Q Diamond phosphostain, we used the strategy of SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ coupled with phospho-specific antibodies to exploit the fact that cTnI harbors multiple phosphorylation sites including protein kinase A and protein kinase C sites, Ser22/Ser23, Ser42/44, and Thr143 and p-21 activated kinase/AMP-kinase site ser150 [40]. Using this technique we were able to detect three distinct bands that represent, based on control experiments, the un-, mono- and bis-phosphorylated (0P, 1P, and 2P, respectively) species of cTnI [41]. Previous work using top down mass spectrometry measures approximately 24% cTnI in the un-phosphorylated form [54] whereas, here, the amount of 0P-cTnITOTAL is influenced by sex and HCM genotype. Taken together, the data presented in the current study illustrate that the amount of quantifiable, un-phosphorylated (and other phosphospecies) depends on mouse strain, age, sample preparation, and, most importantly, methodology for phosphospecies detection (SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ vs. top-down mass spectrometry).

Perhaps more importantly, what becomes apparent from SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ analysis is that the relative distribution of the three phosphospecies is unique for each experimental group. Although the implication is over-stimulation of protein kinase pathways or, alternatively, suppression of phosphatase activity [40] in HCM male hearts, for example, it is likely that multiple cellular mechanisms are responsible for the individual patterning of cTnI phosphorylation. In an attempt to tease out the relationship of cellular signaling and cTnI phosphorylation, we sought to elucidate the site-specific distribution of cTnI phosphospecies. It must be noted that the presence of only three detectable bands in the current study does not rule out the existence of other phosphospecies as indicated in previous work [55]. Instead, the technique of SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ identifies the most abundant phosphospecies within the densitometric range.

To do this, we coupled SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ followed by Western blot using antibodies that target specific sites on cTnI only when phosphorylated. Using the summed band densities as a measure for total phosphorylated-(P)-cTnI-ser23/24, we are able to show that total P-cTnI-ser23/24 is more abundant in HCM male hearts compared to HCM female and WT male hearts. The suggestion is heightened adrenergic drive in HCM male compared to HCM female hearts [50]. Moreover, there is a differential distribution of the alternative phosphospecies, the 1P-cTnI-ser23/24 and 2P-cTnI-ser23/24. Although this differential distribution in P-cTnI-ser23/24 phosphospecies is most likely due to differences in adrenergic signaling, an alternative view is that the myocellular environment in male HCM hearts may not be able to support phosphorylation at one PKA-target site. Interestingly, a previous study using top down mass spectrometry illustrates that phosphorylated Ser23 is slightly more abundant than phosphorylated Ser24 [54], although the functional impact of mono-phosphorylated cTnI at either Ser23 or Ser24 has not been clearly defined.

Nevertheless, if myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity in this R403Q model were dictated solely by phosphorylation of cTnI at the putative PKA sites (P-cTnI-ser23/24), then we would predict a reduction in P-cTnI-ser23/24 in HCM female hearts along with the increased myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity relative to HCM male hearts, which is supported by the current study. Likewise, we would expect a decreased Ca2+-sensitivity in HCM male trabeculae compared to both male and female WT trabeculae, a prediction that is only partly supported by these data. Therefore, we cannot directly attribute the observed pattern of Ca2+-sensitivity to phosphorylation of cTnI-ser23/ 24 alone. The inability of the myofilaments to respond appropriately to adrenergic stimulation could be a mechanistic basis underlying HCM disease progression in male, but not female HCM mice.

The myofilaments act as a nodal point for multiple cellular kinases and cTnI-ser23/24 is one of several target sites on cTnI [40]. Recent reports have identified a P-21 activated kinase and AMP kinase target site on cTnI (cTnI-ser150) and cardiac fibers exchanged with cTnI pseudo-phosphorylated at serine150 have increased Ca2+-sensitivity [44]. Therefore, we further hypothesized that the increase in Ca2+-sensitivity observed in HCM female trabeculae is due to increased phosphorylation at cTnI-ser150. Although our data shows similar levels of P-cTnI-ser150 between all experimental groups, the distribution of P-cTnI-ser150 depends on sex and HCM.

In HCM female hearts, one-third of P-cTnI-ser150 is detected in the, presumably un-phosphorylated 0P band (0P-cTnI-ser150), a significantly greater amount than the other groups. Our supplemental data and previous reports indicate that the phosphospecific cTnI-ser150 antibody targets the Ser150 site only when phosphorylated [47]. Until additional studies are performed such as top-down mass spectrometry on this specific protein band, it is reasonable to conclude that the presumably 0P band harbors at least some of cTnI when phosphorylated at Ser150. Therefore, we conclude that the detection of P-cTnI-ser150 in the 0P band without concomitant phosphorylation at Ser23/24 represents cTnI phosphorylated at Ser150, only. In addition, we can also conclude that, although each band following SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™ most likely represents a unique phosphospecies of cTnI, the categorization of each band as un-, mono-, or bis-phosphorylated may under-represent the existence of alternative cTnI phosphospecies.

Elevated levels of 0P-cTnI-ser150 and 1P-cTnI-ser23/24 are consistent with an overall increase in 0P-cTnITOTAL in HCM female hearts compared to the other experimental groups. Moreover, an increased phosphorylated-cTnI-ser150 is predictive of the increased Ca2+-sensitivity measured in HCM female trabeculae [44]. We further speculate that a reduction in total P-cTnI-ser23/24 may be per-missive to phosphorylation of cTnI at Ser150, which would also predict an increase in Ca2+-sensitivity. However, it is important to note that (1) the quantitative amounts of P-cTnI-ser150 relative to P-cTnI-ser23/24 cannot be determined using SDS–PAGE-Phos-tag™, and (2) the impact of cTnI phosphorylation at alternative target sites, MyHC expression and phosphorylation of other myofilament proteins such as troponin T is not known.

Conclusions

The assertion that HCM is a complex disease is underscored by the difficulty in attributing a single cause to the disease such as aberrant myofilament function. What is evident from studies using the R403Q HCM model is that although the primary defect may reside in the sarcomere, the development of the HCM phenotype depends on the interaction of the initiated signaling pathways, environmental stressors, and individual genotype (including sex/ gender). In this particular study, we show that differences in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity are most likely the result and not the cause of HCM. More importantly, the differential patterning or distribution of cTnI phosphospecies implicates a critical relationship between HCM and cellular signaling pathways and that Ca2+-sensitivity represents a single functional parameter that is the summation of multiple signals as suggested [44]. Finally, although this particular murine model of HCM does not exactly mimic the human genotype, it is a useful tool to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the HCM phenotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Leslie A. Leinwand for providing the HCM mice for the initial studies. This work was supported by NIH grant (HL 098256 and HL50560 [L.A. Leinwand]), by a National and Mentored Research Science Development Award (K01 AR052840) and Independent Scientist Award (K02 HL105799) from the NIH awarded to J.P. Konhilas and the Interdisciplinary Training Grant in Cardiovascular Sciences (HL007249). Support was received from the Sarver Heart Center at the University of Arizona and from the Steven M. Gootter Foundation.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2012.12.023.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; β-MyHC, β-myosin heavy chain; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; PMSF, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; MyHC, myosin heavy chain; PVDF, polyvinylidene fluoride; PKA, protein kinase A; VM, ventricular weight; TL, tibial length; PLB, phospholamban; cTm, cardiac tropomyosin; MLC2, myosin light chain 2; MBP-C, myosin binding protein C; PKC, protein kinase C.

References

- 1.Szczesna D, Zhang R, Zhao J, Jones M, Guzman G, Potter JD. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:624–630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra M, Rundell VL, Tardiff JC, Leinwand LA, De Tombe PP, Solaro RJ. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tardiff JC, Factor SM, Tompkins BD, Hewett TE, Palmer BM, Moore RL, Schwartz S, Robbins J, Leinwand LA. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2800–2811. doi: 10.1172/JCI2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tardiff JC, Hewett TE, Palmer BM, Olsson C, Factor SM, Moore RL, Robbins J, Leinwand LA. J Clin Invest. 1999;104 doi: 10.1172/JCI6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vikstrom KL, Factor SM, Leinwand LA. Mol Med. 1996;2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisterfer-Lowrance AA, Christe M, Conner DA, Ingwall JS, Schoen FJ, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Science. 1996;272:731–734. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuda G, Fananapazir L, Epstein ND, Sellers JR. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1997;18:275–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1018613907574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmiter KA, Tyska MJ, Haeberle JR, Alpert NR, Fananapazir L, Warshaw DM. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2000;21:609–620. doi: 10.1023/a:1005678905119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney HL, Straceski AJ, Leinwand LA, Tikunov BA, Faust L. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1603–1605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashita H, Tyska MJ, Warshaw DM, Lowey S, Trybus KM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28045–28052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer BM, Fishbaugher DE, Schmitt JP, Wang Y, Alpert NR, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, VanBuren P, Maughan DW. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H91–99. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer BM, Wang Y, Teekakirikul P, Hinson JT, Fatkin D, Strouse S, Vanburen P, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Maughan DW. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1939–1947. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00644.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard E, Seidman C, Seidman JG, LeWinter M, Maughan D. Circ Res. 1999;84:475–483. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semsarian C, Ahmad I, Giewat M, Georgakopoulos D, Schmitt JP, McConnell BK, Reiken S, Mende U, Marks AR, Kass DA, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1013–1020. doi: 10.1172/JCI14677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgakopoulos D, Christe ME, Giewat M, Seidman CM, Seidman JG, Kass DA. Nat Med. 1999;5:327–330. doi: 10.1038/6549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stauffer BL, Konhilas JP, Luczak ED, Leinwand LA. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:209–216. doi: 10.1172/JCI24676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konhilas JP, Watson PA, Maass A, Boucek DM, Horn T, Stauffer BL, Luckey SW, Rosenberg P, Leinwand LA. Circ Res. 2006;98:540–548. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205766.97556.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Force T, Bonow RO, Houser SR, Solaro RJ, Hershberger RE, Adhikari B, Anderson ME, Boineau R, Byrne BJ, Cappola TP, Kalluri R, LeWinter MM, Maron MS, Molkentin JD, Ommen SR, Regnier M, Tang WH, Tian R, Konstam MA, Maron BJ, Seidman CE. Circulation. 2010;122:1130–1133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.950089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsson MC, Palmer BM, Stauffer BL, Leinwand LA, Moore RL. Circ Res. 2004;94:201–207. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000111521.40760.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Tombe PP, Solaro RJ. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000;28:991–1001. doi: 10.1114/1.1312189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solaro RJ. In: Physiology and Pathophysiology of the Heart. Sperelakis N, editor. Kluwer Publishers; Boston: 1995. pp. 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kooij V, Saes M, Jaquet K, Zaremba R, Foster DB, Murphy AM, Dos Remedios C, van der Velden J, Stienen GJ. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:954–963. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodor GS, Oakeley AE, Allen PD, Crimmins DL, Ladenson JH, Anderson PA. Circulation. 1997;96:1495–1500. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belin RJ, Sumandea MP, Kobayashi T, Walker LA, Rundell VL, Urboniene D, Yuzhakova M, Ruch SH, Geenen DL, Solaro RJ, de Tombe PP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2344–2353. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00541.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta RC, Neumann J, Boknik P, Watanabe AM. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1138–1144. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.3.H1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Backx PH, Gao WD, Azan-Backx MD, Marban E. J Physiol. 1994;476:487–500. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020149. Lond. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobesh DP, Konhilas JP, de Tombe PP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1055–H1062. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00667.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janssen PML, de Tombe PP. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2415–H2422. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Velden J, Merkus D, de Beer V, Hamdani N, Linke WA, Boontje NM, Stienen GJ, Duncker DJ. Front Physiol. 2011;2:83. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pi Y, Kemnitz KR, Zhang D, Kranias EG, Walker JW. Circ Res. 2002;90:649–656. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000014080.82861.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsson MC, Palmer BM, Leinwand LA, Moore RL. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1136–1144. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyata S, Minobe W, Bristow MR, Leinwand LA. Circ Res. 2000;86:386–390. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadal-Ginard B, Mahdavi V. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1693–1700. doi: 10.1172/JCI114351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tardiff JC, Hewett TE, Factor SM, Vikstrom KL, Robbins J, Leinwand LA. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herron TJ, Korte FS, McDonald KS. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1217–1222. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice R, Guinto P, Dowell-Martino C, He H, Hoyer K, Krenz M, Robbins J, Ingwall JS, Tardiff JC. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;48:979–988. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ford SJ, Mamidi R, Jimenez J, Tardiff JC, Chandra M. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gianni D, Chan J, Gwathmey JK, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37:375–380. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9474-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guinto PJ, Haim TE, Dowell-Martino CC, Sibinga N, Tardiff JC. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H614–626. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01143.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solaro RJ, Kobayashi T. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9935–9940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.197731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikuta E, Takiyama K, Koike T. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:749–757. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500024-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Messer AE, Jacques AM, Marston SB. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliveira SM, Davies J, Carling D, Watkins H, Redwood C. Biophys J. 2009 [Google Scholar]; Biophysical Society Meeting Abstracts. 2009;20a 841-Plat. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nixon BR, Thawornkaiwong A, Jin J, Brundage EA, Little SC, Davis JP, Solaro RJ, Biesiadecki BJ. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19136–19147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.323048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliveira SM, Zhang YH, Solis RS, Isackson H, Bellahcene M, Yavari A, Pinter K, Davies JK, Ge Y, Ashrafian H, Walker JW, Carling D, Watkins H, Casadei B, Redwood C. Circ Res. 2012;110:1192–1201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.259952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sancho-Solis R, Xu L, Ge Y, Walker JW. Biophys J. 2009 [Google Scholar]; Biophysical Society Meeting Abstracts. 2009;20a Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sancho Solis R, Ge Y, Walker JW. Protein Sci: A Publication Protein Soc. 2011;20:894–907. doi: 10.1002/pro.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olivetti G, Giordano G, Corradi D, Melissari M, Lagrasta C, Gambert SR, Anversa P. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1068–1079. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li C, Li J, Cai X, Sun H, Jiao J, Bai T, Zhou XW, Chen X, Gill DL, Tang XD. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40782–40791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.263046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solaro RJ, de Tombe PP. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:616–618. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Konhilas JP, Wolska B, Martin AF, Solaro RJ, de Tombe PP. Biophys J. 2000;78:108A. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kentish JC, McCloskey DT, Layland J, Palmer S, Leiden JM, Martin AF, Solaro RJ. Circ Res. 2001;88:1059–1065. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biesiadecki BJ, Kobayashi T, Walker JS, John Solaro R, de Tombe PP. Circ Res. 2007;100:1486–1493. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000267744.92677.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ayaz-Guner S, Zhang J, Li L, Walker JW, Ge Y. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8161–8170. doi: 10.1021/bi900739f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Messer AE, Gallon CE, McKenna WJ, Dos Remedios CG, Marston SB. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2009;3:1371–1392. doi: 10.1002/prca.200900071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.