Abstract

Progressive renal failure often complicates Fabry’s disease. However, the pathogenesis of Fabry nephropathy is not well understood. We applied unbiased stereological methods to the study of the electron microscopic changes of Fabry nephropathy and the relationship between glomerular structural parameters and renal function in young Fabry patients. Renal biopsies from 14 (M/F=8/6) enzyme replacement therapy (ERT)-naive Fabry patients (median age 12 years; range 4–19 years) and 9 (M/F=6/3) normal living kidney donor control subjects were studied. Podocyte GL-3 inclusion volume density [Vv(Inc/PC)] increased progressively with age, while there was no significant relationship between age and endothelial [Vv(Inc/Endo)] or mesangial [Vv(Inc/Mes)] inclusion volume densities. Foot process width which was greater in male Fabry patients vs. controls also progressively increased with age, and correlated directly with proteinuria. Endothelial fenestration was reduced in Fabry patients vs. controls. These studies are the first to show relationships between quantitative glomerular structural parameters of Fabry nephropathy and urinary protein excretion. The parallel progression with increasing age in podocyte GL-3 accumulation, foot process widening and proteinuria, strongly suggest that podocyte injury may play a pivotal role in the development and progression of Fabry nephropathy.

Introduction

Reduced or absent activity of the lysosomal enzyme α-galactosidase A (α-Gal A) in Fabry disease leads to accumulation of its substrates, primarily globotriaosylceramide (GL-3), resulting in characteristic multi-lamellar lysosomal inclusions, the so-called myelin figures and zebra bodies, in different organs and cell types. Progressive cardiovascular, neurologic and renal complications are hallmarks of the disease, all potentially fatal [3, 4]. Most males and up to 15–20% of female Fabry patients eventually develop severe or end stage renal disease (ESRD) [5], and overt proteinuria is a finding in nearly all these patients [6]. Proteinuria, long considered the first clinical manifestation of Fabry nephropathy, may start as early as 10 years of age [7]. Recent morphologic studies have demonstrated that nephropathy may be prominent even before clinical signs of renal disease become apparent [8, 9]. Once overt proteinuria is established, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) declines inexorably towards ESRD, often by the third to fifth decade of life in males [10], and rarely, as early as 16 years of age [7]. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), if started early, may yet be proven to prevent subsequent vital organ damage [11, 12]. However, once proteinuria is manifest responsiveness to ERT may be incomplete and proteinuria generally does not normalize [13,14]. There are no clear genotype and phenotype correlations, and disease progression is variable among individuals. Moreover, there are no clear guidelines for initiation of ERT in young Fabry patients.

Only few studies focus on early renal pathologic lesions of Fabry disease [8, 15]. Such studies including re-biopsy studies after several years ERT are necessary for the discovery of early morphologic biomarkers of disease progression, which could be used as potential prognostic tools and treatment guides. We have developed unbiased stereological methods to study early glomerular electron microscopic (EM) changes of nephropathy in young Fabry patients and, for the first time, have shown relationships between these structural changes and urinary protein excretion in Fabry patients.

Results

Demographical and clinical characteristics of Fabry patients are summarized in Table 1. Male and female patients were not statistically different in age (Table 2). However, the control subjects were older than the Fabry patients (p=0.0005). Six patients (M/F=3/3) had detectable (>0) urine protein values [urine protein/creatinine ratios (UPCR) 11–251 mg/g or 1.2–28 mg/mmol]. Serum creatinine was normal in all patients where determined (n=10). Four patients with no serum creatinine values had normal blood urea nitrogen (BUN) values (Table 1) Measured (n=8) and estimated (n=2) GFR ranged from 90–183 (median 106) ml/min/1.73 m2. Urinary protein excretion and GFR were not statistically different between male and female Fabry patients. There was a direct relationship between urinary protein excretion rate and age (r=0.57, p=0.03).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of Fabry patients.

| Patient No. | Sex | Age (year) | Angiokeratoma | Acroparesthesia/pain | Corneal opacity | UPCR | S/Cr (mg/dl) | GFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | m | 4 | − | − | − | 0 | 0.5 | >90* |

| 2 | m | 7 | − | − | − | 0 | 0.49 | 183† |

| 3 | f | 8 | + | + | + | 0.04** | NA | NA |

| 4 | f | 9 | − | + | − | 19 | 0.59 | 106† |

| 5 | m | 11 | + | + | + | 0.039** | NA | NA |

| 6 | f | 11 | − | + | + | <0.015 | 0.51 | 105† |

| 7 | m | 12 | + | + | + | 0.039** | NA | NA |

| 8 | f | 12 | − | + | − | 29 | 0.69 | 109† |

| 9 | f | 13 | − | + | + | 0 | 0.81 | 97† |

| 10 | f | 14 | − | + | + | 62 | 0.57 | 90† |

| 11 | m | 15 | + | + | + | 0.1–0.6 (g/d) | 0.75 | NA |

| 12 | m | 16 | + | + | + | 92 | 0.72 | 112† |

| 13 | m | 18 | + | + | + | 251 | 0.87 | 96† |

| 14 | m | 19 | + | + | + | 0.05** | 0.6 | 120‡ |

UPCR= urinary protein creatinine ratio; S/Cr=serum creatinine; GFR=glomerular filtration rate; ND= not detectable per historical records; NA=not available S/Cr or GFR, but blood urea nitrogen value was normal.

GFR values based on clearances of *Cystatin C, †iohexol, or ‡creatinine; **average normal UPCR for age from Ref# 34. Patients (1 and 2), (3 and 7), and (4 and 8) are siblings.

Table 2.

Demographic, renal functional and glomerular structural parameters of Fabry patients and controls.

| Fabry Males (n=8) | Fabry Females (n=6) | Fabry Total (n=14) | Controls (M/F=6/3) (n=9) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14[4–19] | 12[8–14 | 12[4–19] | 32[16–52] | 0.0005‡, 0.0008*, 0.0009** |

| UPCR (mg/g) | 55±90 | 18±25 | 40±71 | NA | NS† |

| Serum Cr (mg/dl) | 0.70±0.15 (n=6) | 0.63±0.12 (n=5) | 0.65±0.13 (n=11) | NA | NS† |

| GFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 120±37 (n=5) | 101±8 (n=5) | 111±27 (n=10) | NA | NS† |

| Vv(Inc/PC) | 0.37±0.11 | 0.26±0.06 | 0.32±0.11 | -- | 0.06† |

| Vv(Inc/Endo) | 0.19±0.12 | 0.03±0.03 | 0.12±0.12 | -- | 0.008† |

| Vv(Inc/Mes) | 0.08±0.06 | 0.03±0.03 | 0.06±0.05 | -- | 0.06† |

| FPW (nm) | 558±133 | 455±67 | 514±118 | 430±61 | 0.06‡, 0.06†, 0.01** |

| % endothelial fenestration | 48±14 | 49±9 | 48±12 | 61±9 | 0.01‡, 0.06*, 0.03** |

All values are mean±SD except for age and urine protein creatinine ratio which are median [range]. To convert UPCR from mg/g to mg/mmol; multiply by 0.887. which are median [range].

Female Fabry vs. control;

male Fabry vs. control;

male vs. female Fabry;

combined male and female Fabry vs. control.

Abbreviations: UPCR= urinary protein creatinine ratio; S/Cr= serum creatinine; GFR=glomerular filtration rate; Vv(Inc/PC)=fractional volume of podocyte GL-3 inclusions per cytoplasm; Vv(Inc/Endo)= fractional volume of endothelial cell GL-3 inclusions per cytoplasm; Vv(Inc/Mes)=mesangial cell GL-3 inclusions per cytoplasm; FPW=foot process width

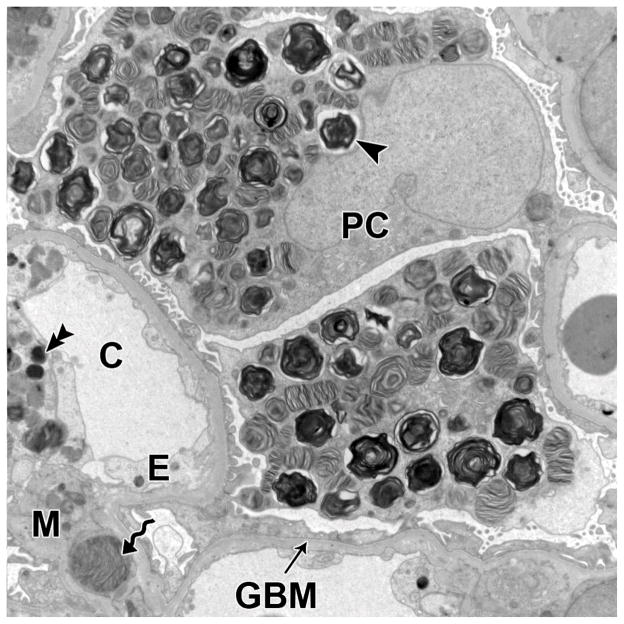

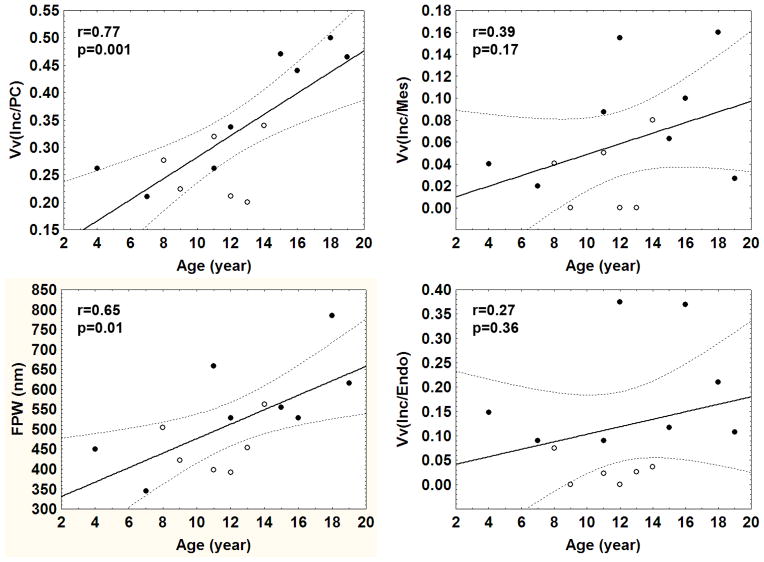

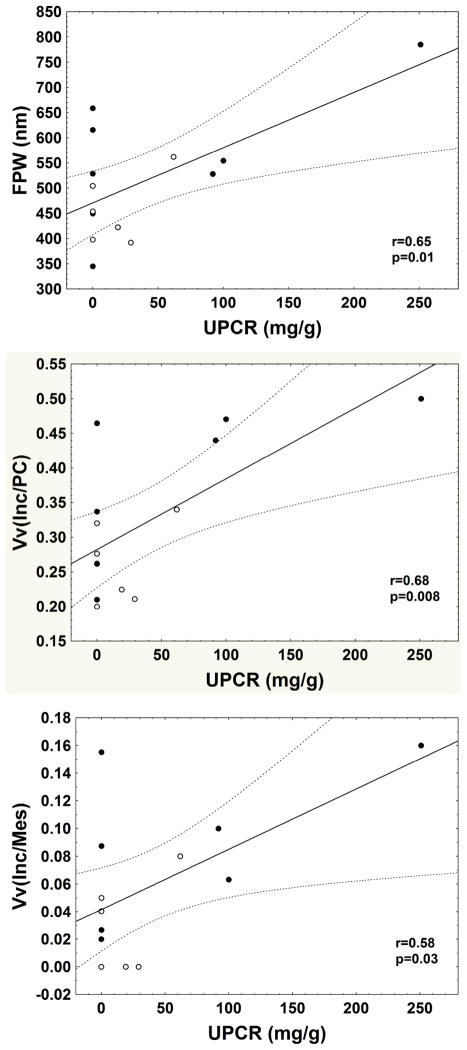

GL-3 inclusions were present in all glomerular cells, and were most abundant in podocytes (Figure 1). These inclusions, although sharing multi-lamellation and electron density, varied in size and shape. Generally, inclusions within mesangial cells were the smallest and within podocytes were the largest. The volume fraction of GL-3 inclusions per podocyte [Vv(Inc/PC)] increased with age, as did podocyte foot process width (FPW), while there was no significant relationship between age and the volume fraction of GL-3 inclusions per endothelial cell [Vv(Inc/Endo)] or per mesangial cell [Vv(Inc/Mes)] (Figure 2). Vv(Inc/PC) correlated directly with proteinuria (r=0.68, p=0.008) (Figure 3) and FPW (r=0.71, p= 0.005). Segmental foot process effacement was present in all glomeruli. Detachment of podocytes from the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) was very rare or absent in most glomeruli (data not shown). There was a trend for greater FPW in the total Fabry cohort than in control subjects (p= 0.06, Table 2).

Figure 1.

GL-3 inclusions in glomerular podocytes (arrowhead), endothelial cells (double arrowhead) and mesangial cells (spiral arrow) from a kidney biopsy of a Fabry patients (TEM, 11,000 x). Abbreviations: PC=podocyte; C=capillary lumen; E=endothelial cell; M=mesangium; GBM=glomerular basement membrane

Figure 2.

Relationship between age and podocyte [Vv(Inc/PC)], mesangial [Vv(Inc/Mes)], and endothelial cell [Vv(Inc/Endo)] GL-3 fractional volume of inclusions per cytoplasm and foot process width (FPW) in Fabry patients. (●=male; ○=female; the bold line is the regression line and the dashed lines are 95% confidence interval boundaries)

Figure 3.

Relationships between urinary protein creatinine ratio (UPCR, mg/g) and foot process width (FPW, nm), GL-3 inclusion fractional volume per podocyte cytoplasm [Vv(Inc/PC)] and mesangial cell cytoplasm [Vv(Inc/Mes)] in Fabry patients. (●=male; ○=female; the bold line is the regression line and the dashed lines are 95% confidence interval boundaries)

Vv(Inc/Endo) was greater in male vs. female patients (p=0.008, Table 2). There were trends for greater Vv(Inc/PC) (p=0.06) and Vv(Inc/Mes) (p=0.06) in males vs. females (Table 2). FPW was greater in male patients vs. control subjects (p=0.01, Table 2), while there was no statistically significant difference in FPW between control subjects and female patients. There was a trend for greater FPW in male vs. female Fabry patients (p=0.06, Table 2). FPW correlated directly with proteinuria (r=0.65, p=0.01) (Figure 3). Vv(Inc/Mes) also correlated directly with Vv(Inc/PC) (r=0.61, p=0.02), FPW (r=0.70, p=0.006) and proteinuria (r=0.58, p=0.03). However, there was no relationship between Vv(Inc/Endo) and proteinuria. There was a direct relationship between Vv(Inc/Mes) and Vv(Inc/Endo) (r=0.76, p=0.002). There was a trend for a direct correlation between Vv(Inc/PC) and Vv(Inc/Endo) (r=0.52, p=0.06). Glomerular endothelial fenestration was reduced in Fabry patients compared to controls (p=0.01, Table 2); this was statistically significant in male patients (p=0.03) but only a trend in female patients (p=0.06). However, there was no statistically significant difference in glomerular endothelial fenestration between male and female Fabry patients. Although the number of cases was limited, there was no trend for a relationship between age and FPW or endothelial fenestration in the controls, nor was there a trend for these parameters to be different between male and female controls. There was no relationship between % endothelial fenestration and Vv(Inc/Endo), age, proteinuria or GFR. Vv(Inc/Endo) was greater in male vs. female patients (p=0.008, Table 2); there were also trends for greater Vv(Inc/PC) (p=0.06) and Vv(Inc/Mes) (p=0.06) in the male Fabry patients (Table 2).

Discussion

This is the first study of glomerular ultrastructural lesions of Fabry nephropathy using unbiased stereological quantitative methods. Furthermore, it is the first study showing age-dependent progressive accumulation of GL-3 deposits in podocytes in a cohort of young Fabry patients with normal GFR with absent or low grade proteinuria. While angiokeratoma corporis diffusum was first described by Fabry in 1898 [16], Fabry renal pathology was only recognized about half a century later by Pompen et al when reporting autopsies of three brothers [17]. More detailed descriptions, including biopsies from children with Fabry disease were published later by Desbois and Gubler et al [15, 18]. In fact, GL-3 inclusions have been described in kidney cells, especially in podocytes, as well as in heart, cornea, and placenta in autopsies of Fabry disease fetuses [19–21]. Concordant with previous studies [8, 15], we identified GL-3 inclusions in all glomerular cell types (podocytes, endothelial and mesangial cells) in our young Fabry patients, including a 4 years old boy.

In a classic paper of Fabry renal pathology, Gubler et al, used a semi-quantitative scoring system for intracellular GL-3 inclusions [15], These authors did not find significant relationships between inclusions in any glomerular cells and age [15], nor did this study detect variations in podocyte GL-3 scores among the patients. Tøndel et al described renal lesions in 9 Fabry children aged 7 to 18 years with normal GFR values, but with slightly elevated urine albumin in 2/3 of patients [8]. Using a light microscopic semi-quantitative method, the scores for GL-3 inclusions in podocytes were virtually identical in all biopsies in this study. No statistically significant relationships were found between inclusion scores in different cell types and age, GFR or proteinuria. Similarly, a recent light microscopy scoring system for renal lesions proposed by the International Study Group of Fabry Nephropathy (ISGFN) did not identify relationships between cellular inclusion scores and renal function [9]. However, most cases in this latter study were adult Fabry patients with mild nephropathy (CKD stage 1–2).

In contrast, the present study of children and adolescents utilizing quantitative stereological EM methods, documented progressive accumulation of podocyte GL-3 inclusions with increasing age. This is likely due to greater precision and perhaps accuracy in EM stereological methods to estimate cellular GL-3 accumulation. Similar to these earlier studies [8, 15], we found it difficult to appreciate differences in inclusion densities in podocytes by light microscopy when, in fact, there was substantial difference by EM stereology [data not presented]. This was, perhaps, especially true for endothelial and mesangial inclusions, which are less abundant and usually smaller than those in podocytes where EM appears to provide even greater precision and sensitivity (data not presented). Systematic uniform random sampling (SURS) is, in fact, an efficient tool to study variable, but not rare, phenomena in biology [22]. SURS is designed to overcome variations in sampling (glomeruli, sections, microscopic fields, etc) efficiently and, in an unbiased way, to unveil the true biologic variation which underlies relationships between parameters, and difference among groups. The methods used in the present studies provide mean values of GL-3 inclusion densities among the sampled cell types. These methods are not suitable to distinguish between uniform vs. heterogeneous distributions of cellular GL-3 inclusion densities. The latter, perhaps, might be posited as an expression of lionization in females.

The progressive accumulation of GL-3 inclusions with age in podocytes and not in the endothelial or mesangial cells may result from different rates of GL-3 production in these different cell types. This may also reflect the rate at which these cells turn over. In contrast to endothelial and mesangial cells, podocytes are thought to be terminally differentiated and to proliferate poorly in response to injury or loss [23]. Podocyte loss is associated with segmental, and eventually global glomerulosclerosis [24], common findings in advanced Fabry nephropathy. Increase in foot process width (FPW), an indicator of podocyte injury, was greater in young male compared to female Fabry patients and to normal subjects in the present study. Tøndel et al. observed qualitative segmental foot process effacement in all young Fabry patients in their study, despite AER within the so-called “normoalbuminuric” range in some of those patients [8]. In fact, AER in normal children of similar age is much lower than the 20 μg/min, the upper limit for “normoalbuminuria” which is conventionally accepted [25]. Moreover, increased leakage of albumin and other proteins across the glomerular filtration barrier may not be detectable in the final urine unless it surpasses tubular reabsorption capacity. Torbjörnsdotter et al documented increased foot process width in “normoalbuminuric” young type 1 diabetic patients compared with normal living kidney donors [26]. The presence of podocyte injury in normoalbuminuric young Fabry patients in the present study suggests that albuminuria/proteinuria is not sensitive enough to detect early kidney injury in Fabry nephropathy. Thus, our findings further strengthen previous observations that clinical parameters alone do not permit a diagnosis of early Fabry nephropathy, but this can be made based on renal biopsy [8, 9]. In addition, renal biopsy is also a useful tool to exclude non-Fabry renal diseases in cases with atypical clinical course, such as rapid decline of renal function or very early development of heavy proteinuria.

Importantly, the present study is the first to find strong relationships between early structural and early functional changes in Fabry renal disease. Foot process width and the fractional volume of GL-3 inclusions in the podocytes correlated with urinary protein excretion rates. ERT leads to a rapid and marked decrease in mesangial and endothelial cell GL-3 inclusions, while podocyte inclusions and proteinuria persist despite this treatment [27–29]. This argues that podocyte inclusions may be of greater pathogenic importance to proteinuria than the mesangial and endothelial cell inclusions. Further support for this thesis comes from the correlation between FPW and proteinuria in Fabry patients, especially in males, and from the correlation of FPW and the fractional volume podocyte inclusions. Nevertheless, endothelial and vascular lesions may still be important in the pathogenesis of renal or extrarenal complications of Fabry disease. We also found a direct relationship between mesangial cell GL-3 inclusion densities, proteinuria and FPW, and this deserves further investigation.

Since progression of proteinuria, especially to levels exceeding 1 g/24 hours is a strong predictor of progression to ESRD in Fabry disease [27,30], these early structural-functional relationships in Fabry nephropathy are likely to be clinically significant. If, as we suspect, it can be established that robust quantitative stereological early measures of structural parameters are predictive of disease progression, then renal biopsy could become an additional tool in Fabry disease prognosis and management, at least until non-invasive biomarkers come along. Such structural predictors could potentially also be used as endpoints for clinical trials. The validity of these speculations remains to be determined in future studies.

The present study included a limited number of female Fabry patients with proteinuria data, and thus, comparison of these values between the sexes may not be statistically informative; however, FPW was greater in boys. There were also trends for less GL-3 inclusions in podocytes and mesangial cells in girls. This gender difference was particularly striking for GL-3 inclusions in endothelial cells (about 6 times less in females). Perhaps residual levels of enzyme activity could explain the lesser GL-3 accumulation in these cells in females.

GL-3 inclusion density in endothelial and in mesangial cells did not progress with age in either sex in this study. Moreover, as noted above, ERT rapidly reduces inclusions in endothelial and mesangial cells while in patients with proteinuria, the disease may progress [11, 31]. Thus, endothelial or mesangial GL-3 inclusion density are probably not the best primary endpoints for clinical trials in Fabry disease.

Endothelial fenestration was reduced in Fabry patients, a finding similar to that we reported in diabetic nephropathy [32]. This could reflect endothelial injury and dysfunction and goes along with findings of reduced nitric oxide bioavailability in endothelial cells of a mouse model of Fabry disease [33].

Our study has some limitations. Although this is the largest biopsy study in young Fabry patients, a larger number of patients might have improved our ability to find certain relationships or group differences. Control subjects were older than Fabry patients in this study. Since previous studies suggested important glomerular structural differences (including podocyte foot process width) between cadaver and living kidney donor biopsies [26, 34], we confined our studies to living donor control subjects. This naturally excluded younger children. Nevertheless, we know of no previous reports suggesting a change in foot process width or endothelial fenestration with age in humans, nor did we find such trends among our control subjects.

In summary, this is the first study to show relationships between proteinuria and early glomerular lesions of Fabry nephropathy in young patients. Longitudinal studies are required to establish the predictive value of these early changes for the ultimate progression of Fabry renal disease. However, the very long natural history of Fabry nephropathy makes such studies difficult to do. However, cross sectional studies at various stages of the disease could be equally informative, as has been the case in diabetic nephropathy [35]. Therefore, additional structural-functional relationship studies at later stages of the disease are required to better understand the progression of these and other structural parameters in relation to important clinical outcomes, such as GFR loss and end-stage renal disease. Nevertheless, the relationships between early structural changes and proteinuria presented here suggest that such studies would prove useful.

Methods

Subjects

Renal biopsies from 14 (M/F = 8/6) ERT-naive Fabry patients (12 [4–19] years-old) were studied by EM stereology. Nine (M/F=6/3) normal living kidney donors served as control subjects. Four Fabry biopsies (from Hôpital Necker, Paris, France) were archived materials with limited available clinical information. Per medical records, these biopsies were from patients with no proteinuria. Average normal urine protein creatinine ratio values for age were used in statistical analyses for these subjects [36]. Recent biopsies were all performed shortly before initiation of ERT and after informed consent was obtained. Both the Norwegian cases and the Minneapolis cases had renal biopsies in order to obtain a baseline evaluation and to make decisions regarding the initiation of ERT. These patients also had clinical symptoms qualifying them for ERT. Protein excretion per gram creatinine was derived from urines obtained close to the date of biopsy. GFR was estimated by the plasma clearance of iohexol (n=8) or creatinine (n=1), or by cystatin C (n=1) levels.

Stereological Methods

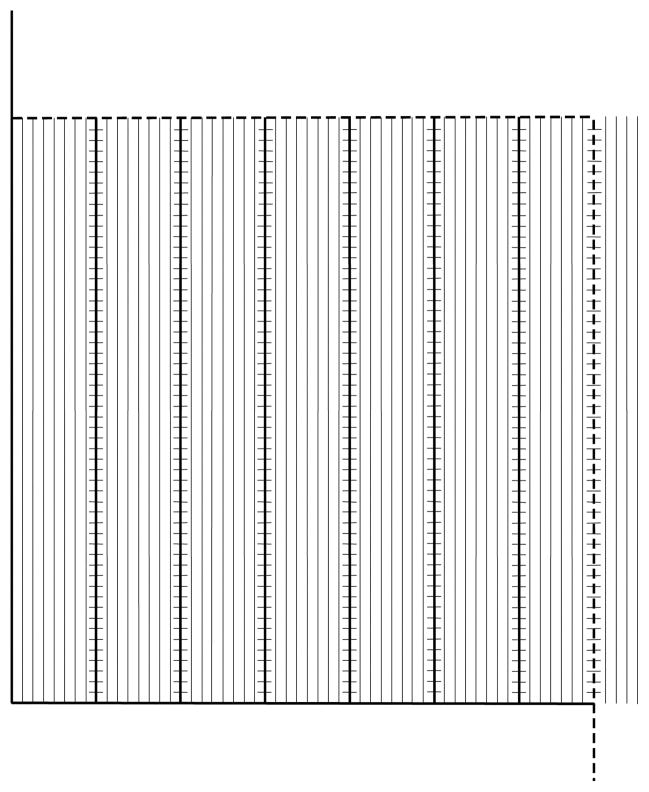

Semithin (1 μm) toluidine blue stained sections were prepared from resin embedded biopsy tissues. The centermost glomerulus with intact Bowman’s capsule and no discernible mechanical artifact in each EM block was selected. Between 1 to 5 glomeruli per biopsy were studied. Thin (60–90 nm) sections were mounted on Formvar-coated slot cupper grids. Digital EM images were taken by a JEOL 100CX TEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) according to a systematic uniform random sampling protocol at 16,000 and 35,000 magnifications. Volume fraction of GL-3 inclusions in podocytes [Vv(Inc/PC)], endothelial [Vv(Inc/Endo)] and mesangial cell cytoplasm [Vv(Inc/Mes)] were estimated on 16,000 x images using a point counting method using grids with the following characteristics: Vv(Inc/PC), points 60 mm apart; Vv(Inc/Endo), points 40 mm apart and 4 fine points per each course point; and Vv(Inc/Mes), coarse points 60 mm apart and 9 fine points per each coarse point. The following equations were used to estimate these parameters: ; and , where FP=fine points; CP=coarse points, Inc=inclusions; PC=podocyte cytoplasm; Endo=endothelial cytoplasm; and Mes=mesangial cytoplasm. A line drawn where the GBM and capillary lumina lost their parallelism was used to define peripheral vs. mesangial components of GBM and capillary lumenal surface. Foot process width (FPW) was estimated as the reciprocal of filtration slit length density [Ls(SP/GBM)] on peripheral GBM on 35,000x images [32]. % endothelial fenestration on the peripheral capillary lumenal surface was estimated on the same images using a line intercept counting method. In brief, an unbiased counting frame (224 × 224 mm) with fine parallel lines 4 mm apart and one course line per 7 fine lines was superimposed on these images (Figure 4). The intercept of each coarse line with capillary lumenal surface was considered non-fenestrated if the distance between the two fenestrae on each side of the coarse line was more than three fine lines, and otherwise it was called fenestrated (Figure 5). % endothelial fenestration was calculated as , where I is the number of grid coarse line intercepts with fenestrated (numerator) or total (denominator) peripheral capillary endothelial coverage.

Figure 4.

The grid used to estimate % endothelial fenestration composed of an unbiased counting frame with inclusion (dashed) and exclusion (continuous) borders, and parallel lines 4 mm apart. There is one coarse line (where the intercepts with endothelial coverage are counted) per seven fine lines. The short lines on the coarse lines are 4 mm apart and, similar to fine lines, are used to define fenestrated vs. non-fenestrated coverage. The endothelial coverage was arbitrarily called non-fenestrated if the distance between the two fenestrae on either side of the coarse line was more than 3 fine and coarse lines, and otherwise it was called fenestrated.

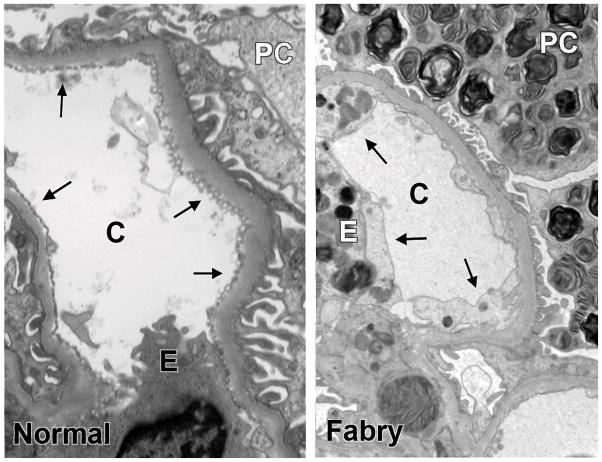

Figure 5.

Comparison of capillary endothelial coverage (arrows) in kidney biopsies from a normal subject (left) and a Fabry patient (right). Note that fenestration is markedly reduced in the Fabry biopsy. Abbreviations: C= capillary; E=endothelial cell; PC=podocyte

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, except for age and urinary protein excretion which are presented as median [range]. Unpaired 2-tailed Student t-test or analysis of variance with least square distance post-hoc test was performed for group comparisons. Linear regression analyses were performed for inter-variable relationships. P values <0.05 were considered to be significant.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor David Warnock for helping us to establish collaborations with International Study Group of Fabry Nephropathy. Also, we thank Ann Palmer and John Basgen for performing electron microscopy and stereological studies and Patricia L. Erickson for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr. Najafian received a travel grant from Genzyme to present part of the data presented in this paper at “Focus on Fabry Nephropathy” satellite meeting of the World Congress of Nephrology 2009, Bergamo, Italy. Dr. Mauer is a member of the Genzyme-sponsored Fabry Registry Board and has been a paid speaker at Genzyme-sponsored events. Dr. Svarstad and Dr. Tøndel have received travel grants from Genzyme and Shire and speakers fee from Genzyme.

References

- 1.Spada M, Pagliardini S, Yasuda M, et al. High incidence of later-onset Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:31–40. doi: 10.1086/504601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meikle PJ, Ranieri E, Ravenscroft EM, et al. Newborn screening for lysosomal storage disorders. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30 (Suppl 2):104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacDermot KD, Holmes A, Miners AH. Anderson-Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 98 hemizygous males. J Med Genet. 2001;38:750–760. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.11.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDermot KD, Holmes A, Miners AH. Anderson-Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 60 obligate carrier females. J Med Genet. 2001;38:769–775. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.11.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilcox WR, Oliveira JP, Hopkin RJ. Females with Fabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93:112–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiffmann R, Warnock DG, Banikazemi M, et al. Fabry disease: progression of nephropathy, and prevalence of cardiac and cerebrovascular events before enzyme replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(7):2102–2111. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheth KJ, Roth DA, Adams MB. Early renal failure in Fabry’s disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1983;2:651–654. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(83)80047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tøndel C, Bostad L, Hirth A, Svarstad E. Renal biopsy findings in children and adolescents with Fabry disease and minimal albuminuria. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:767–76. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.032. Erratum Am J Kidney Dis 2009, 53, 567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogo AB, Bostad L, Svarstad E. Scoring system for renal pathology in Fabry disease: report of the International Study Group of Fabry Nephropathy (ISGFN) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp528. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branton MH, Schiffmann R, Sabnis SG, et al. Natural history of Fabry renal disease: influence of alpha-galactosidase A activity and genetic mutations on clinical course. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:122–138. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiffmann R, Ries M, Timmons M, et al. Long-term therapy with agalsidase alfa for Fabry disease: safety and effects on renal function in a home infusion setting. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:345–54. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehout F, Schwarting A, Beck M, et al. Effects of enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase alfa on glomerular filtration rate in patients with Fabry disease: preliminary data. Acta Paediatr. 2003;5(Suppl 92):14–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00214.x. discussion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiffmann R, Askari H, Timmons M, et al. Weekly enzyme replacement therapy may slow decline of renal function in patients with Fabry disease who are on long-term biweekly dosing. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1576–83. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West M, Nicholls K, Mehta A, et al. Agalsidase alfa and kidney dysfunction in Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1132–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008080870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gubler MC, Lenoir G, Grunfeld JP, et al. Early renal changes in hemizygous and heterozygous patients with Fabry’s disease. Kidney Int. 1978;13:223–35. doi: 10.1038/ki.1978.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fabry J. Ein Beitrag Zur Kenntnis der Purpura haemorrhagica nodularis (Purpura papulosa hemorrhagica Hebrae) Arch Dermatol Syphilis. 1898;43:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pompen AW, Ruiter M, Wyers HJ. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (universale) Fabry, as a sign of an unknown internal disease; two autopsy reports. Acta Med Scand. 1947;128:234–255. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1947.tb06596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desbois JC, Maziere JC, Gubler MC, et al. Fabry’s disease in children. Clinical and biological study of one family. Structure and ultrastructure of the kidney in a hemizygote and a heterozygote. Ann Pediatr (Paris) 1977;24:575–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elleder M, Poupetova H, Kozich V. Fetal pathology in Fabry’s disease and mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Cesk Patol. 1998;34:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desnick RJ, Allen KY, Desnick SJ, et al. Fabry’s disease: enzymatic diagnosis of hemizygotes and heterozygotes. Alpha-galactosidase activities in plasma, serum, urine, and leukocytes. J Lab Clin Med. 1973;81:157–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsutsumi O, Sato M, Sato K, et al. Early prenatal diagnosis of inborn error of metabolism: a case report of a fetus affected with Fabry’s disease. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;11:39–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1985.tb00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction. J Microsc. 1987;147:229–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shankland SJ. The podocyte’s response to injury: role in proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2131–2147. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kriz W, Gretz N, Lemley KV. Progression of glomerular diseases: is the podocyte the culprit? Kidney Int. 1998;54:687–697. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rademacher E, Mauer M, Jacobs DRJ, et al. Albumin excretion rate in normal adolescents: relation to insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk factors and comparisons to type 1 diabetes mellitus patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:998-998–1005. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04631007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torbjörnsdotter TB, Perrin NE, Jaremko GA, Berg UB. Widening of foot processes in normoalbuminuric adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:750–758. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Germain DP, Waldek S, Banikazemi M, et al. Sustained, long-term renal stabilization after 54 months of agalsidase beta therapy in patients with Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1547–57. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurberg BL, Rennke H, Colvin RB, et al. Globotriaosylceramide accumulation in the Fabry kidney is cleared from multiple cell types after enzyme replacement therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1933–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubanda JC, Anijalg E, Bzdúch V, et al. Evaluation of a low dose, after a standard therapeutic dose, of agalsidase beta during enzyme replacement therapy in patients with Fabry disease. Genet Med. 2009;11:256–64. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181981d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wanner C, Oliveira JP, Ortiz A, et al. Prognostic Indicators of Renal Disease Progression in Adults with Fabry Disease: Natural History Data from the Fabry Registry. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 doi: 10.2215/CJN.04340510. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banikazemi M, Bultas J, Waldek S, et al. Agalsidase-beta therapy for advanced Fabry disease: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146:77–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyoda M, Najafian B, Kim Y, et al. Podocyte detachment and reduced glomerular capillary endothelial fenestration in human type 1 diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2007;56:2155–60. doi: 10.2337/db07-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shu L, Park JL, Byun J, et al. Decreased Nitric Oxide Bioavailability in a Mouse Model of Fabry Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1975–85. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caramori ML, Basgen JM, Mauer M. Glomerular structure in the normal human kidney: differences between living and cadaver donors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1901–3. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000075554.31464.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caramori ML, Kim Y, Huang C, et al. Cellular basis of diabetic nephropathy: 1. Study design and renal structural-functional relationships in patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:506–13. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.506. Erratum in: Diabetes 2002, 51, 1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houser M. Assessment of proteinuria using random urine samples. J Pediatr. 1984;104:845–848. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]