Abstract

Introduction

Klippel–Feil syndrome (KFS) is a congenital cervical vertebral union caused by a failure of segmentation during abnormal development and frequently accompanies conditions such as basicranial malformation, atlas assimilation, or dens malformation. Especially in basilar invagination (BI), which is a dislocation of the dens in an upper direction, compression of the spinomedullary junction from the ventral side results in paralysis, and treatment is required.

Clinical presentation

We present the case of a 38-year-old male patient with KFS and severe BI. Plane radiographs and computed tomography (CT) images showed severe BI, and magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed spinal cord compression caused by invagination of the dens into the foramen magnum and atlantoaxial subluxation. Reduction by halo vest and skeletal traction were not successful. Occipitocervical fusion along with decompression of the foramen magnum, C1 laminectomy, and reduction using instruments were performed. Paralysis was temporarily aggravated and then gradually improved. Unsupported walking was achieved 24 months after surgery, and activities of daily life could be independently performed at the same time. CT and MRI revealed that dramatic reduction of vertical subluxation and spinal cord decompression were achieved.

Conclusion

Reduction and internal fixation using instrumentation are effective techniques for KFS with BI; however, caution should be exercised because of the possibility of paralysis caused by intraoperative reduction.

Keywords: Klippel–Feil syndrome, Occipitocervical malformation, Basilar invagination, Surgical treatment

Introduction

In 1912, Klippel and Feil reported cases of defects in the number of cervical vertebrae in patients with three characteristics: an extremely short neck, low hairline, and significant restriction of range of neck movement [14]. The definition of Klippel–Feil syndrome (KFS) has changed historically in accordance with the combination of congenital cervical union and various accompanying deformities, but currently cases with congenital cervical union are collectively defined as KFS [23]. This syndrome is a congenital union of cervical vertebrae caused by failure of segmentation during abnormal development and frequently accompanies conditions such as basicranial malformation, atlas assimilation, or dens malformation [23]. Especially in basilar invagination (BI), which is a dislocation of the dens in an upper direction, compression of the spinomedullary junction from the ventral side results in paralysis, and treatment is required.

We report a case of KFS with severe BI, in which posterior spinal decompression followed by reduction and internal fixation with cervical pedicle screw instrumentation resulted in a good outcome.

Case report

Informed consent was obtained from the patients. The subject was a 38-year-old man with numbness of the upper and lower limbs for 10 years. Increased numbness and gait disturbance appeared 1 month before he visited our hospital. His father had brevicollis, and the subject had shortness and webbing of the neck (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A thirty-eight year-old man with short neck and webbing of neck

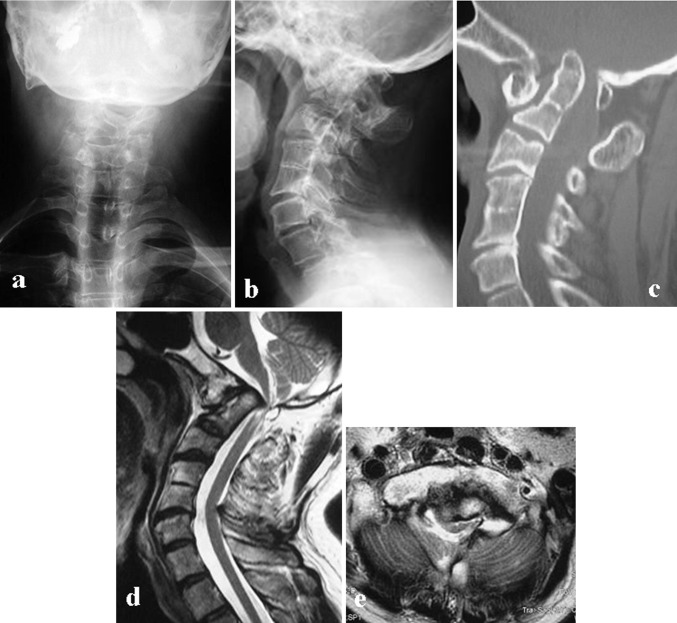

Neurological findings included spastic gait, skill-movement disorder, hyperreflexia, clonus, and hypesthesia of bilateral forearms, hands, and the left lower limb. The score according to the Japanese Orthopaedic Association scoring system (JOA score) [11] was 12 and that according to the Nurick scale [19] was 3 degrees. Radiographs revealed assimilation of the C4–5 vertebrae, atlantoaxial subluxation (AAS), and BI. The atlantodental interval (ADI) [8] was 4 mm; Redlund-Johnell value [26], 20 mm; and Ranawat value [24], 4 mm (Fig. 2a, b). A sagittal computed tomography (CT) reconstruction image showed posterior deviation of the dens, which was invaginated into the foramen magnum; the clivo-axial angle [15] was 95 degrees (Fig. 2c). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed marked anterior compression and flattening of the spinal cord caused by the dens at the C1 level. The T2-weighted image showed high intensity, and the cervicomedullary angle [1] was decreased to 130 degrees (Fig. 2d, e). The diagnosis was myelopathy caused by severe BI in KFS. Feil classification was type II [6]. After hospitalization, a halo vest (Depuy-ACE, Warsaw, IN, USA) was fitted, and reduction of subluxations by manual traction was attempted, but was not possible (Fig. 3a). However, MRI revealed slight improvement of spinal cord compression after manual halo traction was applied (Fig. 3b). As improvement of symptoms was not observed, surgery was performed 1 month later.

Fig. 2.

a Frontal view, plain radiograph. b Lateral view, plain radiograph. C4, 5 assimilation vertebra, atlantoaxial subluxation, and basilar invagination were observed. c CT sagittal image. Dens invaginated into the foramen magnum and showing marked posterior deviation. The clivo-axial angle was 95°. d MRI T2 sagittal image. Marked compression of spinal cord by the dens from the frontal side was observed. The cervicomedullary angle was 130°. e MRI T2 axial image. Flattening of spinal cord by posterior deviation of the dens

Fig. 3.

a Plain radiograph lateral image after traction by halo vest. Basilar invagination was not reduced. b MRI T2 sagittal image. Compression of the spinal cord by the dens from the frontal side was slightly decreased

Operation

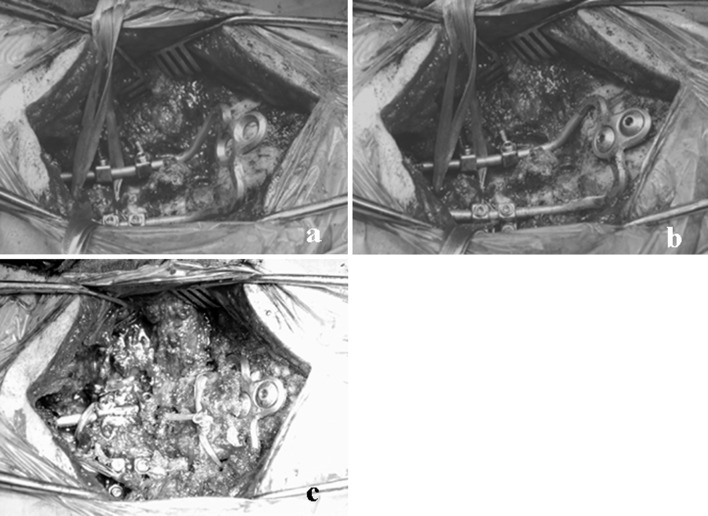

The surgical plan was to perform reduction of BI by the posterior approach; if reduction failed, a secondary procedure would be performed by the anterior approach. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia with fibroscopic endotracheal intubation. The patient was placed in a prone position, and a halo tongue was connected to the surgical bed by a special adaptor (Surgical Bed Adapter; PMT, Inc. Chanhassen, MN, USA). The posterior part of the halo vest was removed to obtain a clear posterior surgical field. Electrodes for muscle evoked potentials following transcranial electrical stimulation (MEP, D-185 MultiPulse Cortical Stimulator, Digitimer Ltd., Letchworth Garden, UK) were placed on the skull, thenar, and plantar surfaces. Under anesthesia, the C2 spinous process was pushed and anterior translation of the C2 spinous process was observed on imaging. An incision was made from the occipital bone to the cervical lamina, and posterior soft tissues from the contracture around the occipitocervical junction were released. Pedicle screws were inserted into the left C2, right C3, and both C4 under CT-guided navigation (Stealth Station TREON™; Medtronic, Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN, USA). Decompression of the foramen magnum and C1 laminectomy were performed, and a pre-bent plate–rod (RRS Loop Spinal System, Robert Leid, Tokyo, Japan) was connected to pedicle screws (Fig. 4a) to achieve reduction position. In the plate–rod type used, screws were inserted in the thick central part of occipital bone. The plate–rod angle was bent to make the angle smaller than that between occipital bone and cervical vertebra and set the occipito-plate 10 mm away from occipital bone. The C2 spinous process was pushed under radiographic guidance, and anterior translation of the C2 vertebral body was achieved. Then, the occipital screw was inserted where the plate touched the occipital bone (Fig. 4b). This procedure was performed to reduce bulbar and spinal cord compression by creating an anterior tilt of the odontoid process. In addition, sublaminar wiring with high-density polyethylene tape (Nesplon tape, Alfresa, Osaka, Japan) was added to C4 and an autograft collected from the iliac bone was transplanted here (Fig. 4c). MEP was monitored during this surgery, and no abnormal waveform was observed.

Fig. 4.

a Decompression of the foramen magnum and C1 laminectomy were performed, and a rod (pre-bent to achieve reduction position) was connected to the pedicle screws. b Using an image intensifier, the C2 spinous process was gently pushed forward, and the plate part of the rod was contacted to the occipital bone and fixed by an occipital screw. c Sublaminar wiring with high-density polyethylene tape was added to C4, and autografted iliac bone was transplanted

Postoperative course

The halo vest was removed and a neck brace was fixed after surgery. The patient was kept in an intensive care unit to confirm the absence of airway obstruction and dysphagia. The day after surgery, the subject was moved to a general ward where ambulation was started immediately. Numbness of upper limbs and skill-movement disorder improved immediately after surgery. However, difficulty in urination and numbness of the left lower limb appeared 4 days after surgery. At this time, imaging results showed good decompression of the spinal cord and no new compression. Rehabilitation continued, and urination without help became possible 1 month after surgery. Unsupported walking was achieved 1 year after surgery. Sensation in the left lower limb improved to the preoperative level 24 months after surgery. At 24 months after surgery, complete bony union was achieved, with ADI, Redlund-Johnell value, and Ranawat value being 2, 25, and 11 mm, respectively, thus showing improvement of BI. On radiographs, the clivo-axial angle and CM angle showed improvement to 125 degrees and 150 degrees, respectively. However, the high intensity on MRI persisted (Fig. 5). JOA score and Nurick score improved to 14 points and 1 degree, respectively.

Fig. 5.

a, b Plain radiograph obtained 24 months after surgery. Good spinal alignment and bony union were achieved. c CT sagittal image. Basilar invagination was reduced, and a clivo-axial angle of 125° was achieved. d MRI T2 sagittal image. Spinal cord compression by the dens was relieved, and the cervicomedullary angle was improved to 150°. However, high intensity of the spinal cord persisted on the image

Discussion

Disorders of the occipitocervical junction with severe BI should be surgically treated if reduction is not achieved by flexion and extension movement or with traction. In surgery, there is controversy regarding whether an anterior or posterior approach should be used. Anterior decompression by the transoral approach or mandibular split is indicated if the compression lesion of the spinal cord is located in an anterior position [25]. This approach is optimal for decompression of the medulla–cervical junction. However, compared to the posterior approach, the anterior approach has drawbacks, including a more complicated technique, higher invasiveness, difficulty in primary fixation, higher incidence of postoperative infection, and increased incidence of respiratory tract disorders [3, 12, 13]. Jones et al. [12] reported that 7 of 44 patients had complications such as dysphagia, nasal escape, nasal regurgitation, and infection. In contrast, reduction by posterior instrumentation is feasible in many cases, because bony compression can be resolved by the reduction of abnormally positioned bone without the above-mentioned complications. Therefore, the posterior approach is increasingly used at present. Internal fixation by the posterior approach can achieve rigid fixation and does not require supportive external fixation such as a halo vest. As a result, early ambulation is easily achieved [10]. However, spinal cord decompression could be insufficient if the reduction is not successful.

The surgical procedure involves either in situ fixation after preoperative reduction by halo vest and traction or reduction and fixation by intraoperative instrumentation. The advantage of in situ fixation using preoperative reduction by halo vest or direct traction is that informed consent can be obtained, because neurological improvement can be achieved by preoperative conscious reduction [20]. However, reduction is occasionally imperfect or incomplete [2, 14, 27]. In contrast, intraoperative reduction by instrumentation is easier because it is performed under general anesthesia [1]. However, postoperative respiratory paralysis or dysphagia may occur [17, 28].

In the present case, primary anterior decompression was judged to be difficult because the invaginated dens was deviated to the posterior side above the skull base. BI has been reported to be reduced by halo traction [20, 27] or direct traction [2], but this was not achieved by manual halo traction in this case. Manual halo traction alone was performed in accordance with the procedure reported by Ogihara et al. [10]. However, direct traction on the bed or traction on the halo chair with weight can be chosen instead. MRI performed after halo vest fixation revealed slight decompression of spinal pressure caused by the odontoid process and it appeared that the fusion in the medulla–cervical junction was not rigid. Therefore, the posterior approach was selected as the primary procedure with the precondition that if correction should be insufficient and/or symptomatic and if improvement was not observed postoperatively, a subsequent operation would be performed using the anterior approach. This procedure was chosen because we predicted that under general anesthesia, the odontoid process could be translated anteriorly by pressing the C2 spinous process forward to achieve decompression. If the clivo-axial angle could be improved, fixation by posterior approach alone might be feasible. Abumi et al. [1] showed that the plate–rod fixed to the occipital bone, which was bent to a smaller angle than the angle between the occipital bone and cervical spine, was then tightened with a nut to the pedicle screw to reduce hyperextension of cervical vertebrae and achieve anterior translation of C2. Peng et al. [22] suggested bending the occipitocervical rod to 110–120° and setting the occipital plate 5–10 mm away from the occipital bone before inserting the occipital screw into the plate to tilt the odontoid process. As posterior translation of C2 by tightening the nut may occur in Abumi’s procedure, we modified the method of Peng and fixed the plate–rod to the pedicle screw first and then manually pushed C2 to achieve anterior translation. However, because the risk of paralysis existed as this procedure was performed, it was not feasible to repeat the reduction, and it was favorable to perform the surgery with both an image intensifier and spinal cord monitoring. While selecting instrumentation, a plate that can insert screws into the thick cortical bone of the central occipital bone and a pedicle screw with high pull-out force were chosen to maintain occipitocervical alignment. The important factors in achieving posterior reduction of BI are absence of bony fusion of the occipitocervical junction, sufficient release of soft tissues around the occipitocervical junction, and selection of instrumentation to achieve rigid fixation.

Table 1 shows complications occurring after posterior occipitocervical reconstruction. Complications related to the surgical procedure, such as screw loosening, nonfusion, dural tear, and infection, are most common, but were not seen in our case. This patient also did not show any airway obstruction and dysphagia. However, even though good reduction of occipitocervical alignment was achieved postoperatively by intraoperative reduction and rigid fixation by instrumentation, paralysis was exacerbated 4 days after surgery in this case. Because no abnormal findings were observed during intraoperative spinal monitoring and paralysis occurred several days after surgery, it was possible that spinal cord compression may have occurred because of a lesion such as a hematoma. However, no abnormal findings were observed on CT or MRI; therefore, the cause was unknown. Fortunately, paralysis was alleviated with continued rehabilitation, and the patient returned to work 2 years after surgery. Generally, excessive reduction during surgery has a higher risk of exacerbating paralysis, and moderate reduction may achieve a clinically sufficient result [16]. The findings of the present case show that it is important not to be overly focused on the degree of reduction.

Table 1.

Occipitocervical fusion complications

| Series | Description of patients | Complications |

|---|---|---|

| Abumi et al. [1] | 26 patients treated with OC fusion using a plate–rod system Fusion achieved in 24/26 cases |

Screw mispositioning (4/64 screws) Cerebrospinal fluid leakage (1 case) Deep wound infection (1 case) |

| Deutsch et al. [4] | 58 nonconsecutive patients treated with OC fusion Fusion achieved in 48/51 cases |

Nonfusion (3 cases) Wound infection (4 cases) Occipital neuralgia (1 case) |

| Fehlings et al. [5] | 16 patients treated with OC fusion using a wire–rod system Fusion achieved in 15/16 cases |

Nonfusion (1 case) Instrumentation loosening (1 case) Occipital decubitus (1 case) Wound infection (1 case) |

| Grob et al. [7] | 39 patients treated with OC fusion using Y-plate screw–rod fixation Fusion achieved in 22/22 cases |

Retropharyngeal wall injury (1 case) Infection (1 case) C5 syndrome caused by screw misplacement (1 case) |

| Hsu et al. [9] | 9 patients treated with OC fusion using screw–rod system 9/9 cases achieved fusion |

Deep wound infection (1 case) |

| Nockels et al. [18] | 69 patients treated with OC fusion using screw–rod system 64/62 cases achieved fusion |

Nonfusion (2 cases) Infection (2 cases) Screw fracture (1 case) Plate fracture (1 case) |

| Miyata et al. [17] | 29 patients treated with OC fusion using plate–rod system No mention about fusion |

Dysphagia (5 cases) Dyspnea (1 case) |

| Ogihara et al. [21] | 23 patients treated with OC fusion using plate–rod system assisted by navigation 23/23 cases achieved fusion |

Screw mispositioning (1/88 screws) Occipital screw backout (1 case) |

| Tagawa et al. [28] | A patient treated with OC fusion Case report |

Airway obstruction (1 case) |

OC occipitocervical

This procedure is a useful surgical technique for disorders of the occipitocervical junction that cannot be reduced by conservative measures to achieve good spinal alignment. However, unpredictable postoperative paralysis should be taken into account in malformation cases.

Conclusions

Surgical treatment was performed for Klippel–Feil syndrome with severe basilar invagination. Basilar invagination could not be reduced by conservative combination treatment using a halo vest and direct traction. Gentle intraoperative reduction achieved good spinal alignment and reduction of basilar invagination. Paralysis was exacerbated immediately after surgery, but was alleviated within 24 months after surgery. This procedure is effective for difficult reduction cases, but unpredictable paralysis after surgery should be taken into account.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff members of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Shinshu University, School of Medicine.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing or financial interests to disclose in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Abumi K, Takeda T, Shono Y, Kaneda K, Fujiya M. Posterior occipitocervical reconstruction using cervical pedicle screws and plate–rod systems. Spine. 1999;24:1425–1434. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199907150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botelho RV, Neto EB, Patriota GC, Daniel JW, Dumont PAS, Rotta JM. Basilar invagination: craniocervical instability treated with cervical traction and occipitocervical fixation. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:444–449. doi: 10.3171/SPI-07/10/444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crokard HA. Transoral surgery: some lessons learned. Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9:283–293. doi: 10.1080/02688699550041304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deutsch H, Haid RW, Rodts GE, Mummaneni PV. Occipitocervical fixation: long-term results. Spine. 2005;30:530–535. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154715.88911.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fehlings MG, Errico T, Cooper P, Benjamin V, DiBartolo T. Occipitocervical fusion with a five-millimeter malleable rod and segmental fixation. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:198–208. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feil A (1919) L’absebce et la diminuation des vertebres cervicales (etude cliniqueel pathogenique): le syndrome dereduction numerique cervicales. Theses de Paris

- 7.Grob D, Schutz U, Plotz G. Occipitocervical fusion in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;366:46–53. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinck VC, Hopkins CE. Measurement of the atlanto-dental interval in the adult. Am J Roentgenol. 1960;84:945–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu YH, Liang ML, Yen YS, Cheng H, Huang CI, Huang WC. Use of screw–rod system in occipitocervical fixation. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:20–28. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain VK, Mittal P, Banerji D, et al. Posterior occipitoaxial fusion for atrantoaxial dislocation associated with occipitalized atlas. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:559–564. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.4.0559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Japanese Orthopaedic Association scoring system for cervical myelopathy (1994) J Orthop Assoc 68:490–503 (Jpn)

- 12.Jones DC, Hayter P, Vaughan D, Findley GFG. Oropharyngeal morbidity following transoral approaches to the upper cervical spine. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;7:295–298. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80618-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanamori Y, Miyamoto K, Hosoe H, Fujitsuka H, Tatematsu N, Shimizu K. Case report. Transoral approach using the mandibular osteotomy for atlantoaxial vertical subluxation in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis associated with mandibular micrognathia. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:221–224. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200304000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klippel M, Feil A. Un cas d’absence des vertebras cervicales avec cage thoracique remontant jusqu’s base du craine. Nouv Icon Salpetriere. 1912;25:223. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menezes AH, Vangilder JC, Graf CJ, Mcdonnel DE. Craniocervical abnormalities: a comprehensive surgical approach. J Neurosurg. 1980;53:444–455. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.4.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyamoto K, Shimizu K, Sakaguchi Y, Sugiyama S, Kodama H, Nishimoto H. Perioperative management of the surgical treatment using halo vest for the cranio-cervical junction and cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Bessatsu Seikeigeka. 2001;40:78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyata M, Neo M, Fujibayashi S, Ito H, Takemoto M, Nakamura K. O–C2 Angle as a predictor of dyspnea and/or dysphagia after occipitocervical fusion. Spine. 2009;54:184–188. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ff64e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nockels RP, Shaffrey CI, Kanter AS, Azeem S, York JE. Occipitocervical fusion with rigid internal fixation: long-term follow-up data in 69 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:117–123. doi: 10.3171/SPI-07/08/117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurick S. The pathogenesis of the spinal cord disorder associated with cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1972;95:87–100. doi: 10.1093/brain/95.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogihara N, Takahashi J, Hirabayashi H, Hashidate H, Mukaiyama K, Kato H. Stable reconstruction using halo vest for unstable upper cervical spine and occipitocervical instability. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1973-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogihara N, Takahashi J, Hirabayashi H, Hashidate H, Kato H. Long-term results of computer-assisted posterior occipitocervical reconstruction. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:723–729. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng X, Chen L, Wan Y, Zou X. Treatment of primary basilar invagination by cervical traction and posterior instrumented reduction together with occipitocervical fusion. Spine. 2011;36:1528–1531. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f804ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pizzutillo PD. Klippel–Feil syndrome. In: Clark CR, editor. The cervical spine. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 448–458. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranawat CS, O‘Leary P, Pellicci P, Tsairis P, Marchisello P, Dorr L. Cervical spine fusion in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:1003–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothman RH, Simeone FA. The spine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992. pp. 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudlund-Johnell I, Pettersson H. Radiographic measurements of the cranio-vertebral region. Designed for evaluation of abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Radiol Diagn. 1984;25:23–28. doi: 10.1177/028418518402500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simsek S, Yigitkanli K, Belen D, Bavbek M. Halo traction in basilar invagination: technical case report. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tagawa T, Akeda K, Asamura Y, Miyabe M, Arisaka H, Furuya M. Upper airway obstruction associated with flexed cervical position after posterior occipitocervical fusion. J Anesth. 2011;25:120–122. doi: 10.1007/s00540-010-1069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]