Abstract

Objectives

The thrombin inhibitor dabigatran is mainly excreted by the kidneys. We investigated whether the recommended method for estimation of renal function used in the clinical trials, the Cockcroft-Gault (CGold) equation and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) modification of diet in renal disease equation 4 (MDRD4), differ in elderly participants, resulting in erroneously higher dose recommendations of dabigatran, which might explain the serious, even fatal, bleeding reported. The renally excreted drugs gabapentin and valaciclovir were also included for comparison.

Design

A retrospective data simulation study.

Participants

Participants 65 years and older included in six different studies.

Main outcome measure

Estimated renal function by CG based on uncompensated (‘old Jaffe’ method) creatinine (CGold) or by MDRD4 based on standardised compensated P-creatinine traceable to isotope-dilution mass spectrometry, and the resulting doses.

Results

790 participants (432 females), mean age (±SD) 77.6±5.7 years. Mean estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) by the CGold equation was 44.2±14.8 ml/min, versus eGFR 59.6±20.7 ml/min/1.73 m2 with MDRD4 (p<0.001), absolute median difference 13.5, 95% CI 12.9 to 14.2. MDRD4 gave a significantly higher mean dose (valaciclovir +21%, dabigatran +25% and gabapentin +37%) of all drugs (p<0.001). With MDRD4 58% of the women would be recommended a full dose of dabigatran compared with 18% if CGold is used.

Conclusions

MDRD4 would result in higher recommended doses of the three studied drugs to elderly participants compared with CG, particularly in women, and thus increased the risk of dose and concentration-dependent adverse reactions. It is important to know which method of estimation of renal function the Summary of Products Characteristics was based on, and use only that one when prescribing renally excreted drugs with narrow safety window. Doses based on recently developed methods for estimation of renal function may be associated with considerable risk of overtreatment in the elderly.

Keywords: Clinical Pharmacology, Geriatric Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

The thrombin inhibitor dabigatran is eliminated by renal excretion. Severe bleeding, even fatal, was reported, mainly in elderly patients with impaired renal function.

Dosing should be adjusted according to renal function, that is, by the Cockcroft-Gault equation. However, in many countries the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) abbreviated modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD4) equation 4 is used in clinical practice for estimation of renal function.

We studied whether use of MDRD4 would show different estimates and thus different recommended doses for dabigatran and for two other renally excreted drugs, gabapentin and valaciclovir, in a group of elderly patients.

Key messages

A significantly larger group of elderly participants would receive a higher dose of the three drugs if MDRD4 was used for determination of dose. This may be one explanation of the cases of serious haemorrhage reported for dabigatran and central nervous system side effects for gabapentin and valaciclovir.

A method to optimise ongoing therapy is to determine plasma concentrations of the drug—(TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring).

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strength of this study is the number of elderly participants and the different settings from where they were recruited, reflecting a mean of the older Swedish population.

Limitations are that this is a data simulation study and no dabigatran, gabapentin, or valaciclovir dose has been given to the participants.

In addition, we have not performed any gold-standard methods, such as iohexol clearance, to elucidate the true GFR in the studied participants.

Introduction

The oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) is marketed as an alternative to warfarin for prevention of venous thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation. Dabigatran etexilate is a prodrug metabolised to the active species dabigatran, which is eliminated primarily by the kidneys. Renal function is therefore an important factor for its clearance rate.1 2

Serious cases of haemorrhage, even fatal, have been reported with the drug,3–5 mainly in elderly patients with severe renal impairment.4 6 Haemorrhage is a dose-dependent and concentration-dependent adverse reaction, shown during the clinical trials with the drug, and the risk for haemorrhage increases in patients with low renal function.7 To prevent this serious risk, renal function should be evaluated by estimation of creatinine clearance including age, sex, serum creatinine and weight, based on the equation that was used during the clinical trials, presented as absolute values (ml/min; Cockcroft-Gault ie, CG).8 Later methods, such as the original modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) equation, the abbreviated MDRD equation 4 (MDRD4), and the chronic kidney disease epidemiology initiative (CKD-Epi) equation have been introduced providing estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as a relative value of ml/min/1.73 m2.9–11 In many countries, MDRD4 is used in clinical practice. Recently, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued draft guidance for industry that suggested that both CG and MDRD can be used for pharmacokinetic studies in patients with impaired renal function.1 The latter equation uses standardised serum creatinine concentrations traceable to isotope-dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS), resulting in a lower serum creatinine concentration compared with the old Jaffe method.12–15 The MDRD formula has shown to provide significantly higher eGFR values in the elderly, potentially resulting in higher dabigatran doses and increased risk for adverse drug reactions (ADRs)16–19 For the purpose of the present study we also studied two other drugs dependent on renal function; gabapentin, that is excreted unchanged by the kidneys, and valaciclovir, that forms a toxic metabolite accumulating in patients with renal impairment.20

Participants and methods

Data from participants 65 years and older were compiled from six different studies on renal function among the elderly. All participants were Caucasians. One study was performed in a home care centre (N=88)21: four studies were performed at an intermediary care unit of internal medicine within the emergency department (N=270),18 22–24 all in Stockholm; and finally, a study of 75-year-old participants was performed in the city of Västerås (N=432).25 We simulated the doses of dabigatran that these participants would be prescribed based on their renal function, that is, 300 mg if creatinine clearance is higher than 50 ml/min; 220 mg if creatinine clearance is 30–50 ml/min and associated with high risk of bleeding; and finally contraindicated if creatinine clearance is less than 30 ml/min. The rationale behind our stratification is that exposure to dabigatran increases from threefold to sixfold in patients with moderate and severe renal impairment.26 Patient characteristics, such as weight, height, age and sex were recorded. Complete data were retrieved for 790 participants, 432 women and 358 men (table 1). Ethical approval was obtained for five studies; the sixth was a local quality assessment not requiring ethical approval in Sweden. From the six studies, only laboratory and demographic data of the included participants were received by the investigators and all other information was blinded.

Table 1.

Demographic data (age, sex, weight, length, BSA and BMI) for 790 individuals aged 65 and older divided between men and women in Sweden from six different studies of the elderly

| All (N=790) | Female (N=432) | Male (N=358) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 77.6±5.7 | 78.0±6.0 | 77.1±5.2 | 0.022 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.2±13.9 | 66.0±14.0 | 75.2±12.1 | <0.0001 |

| Height (cm) (N=590) | 167±8.6 | 161.3±5.5* | 174.0±6.1† | <0.0001 |

| BSA (m2) (N=590) | 1.8±0.18 | 1.7±0.17* | 1.9±0.14† | <0.0001 |

| BMI (N=590) | 25.5±4.2 | 25.7±4.6* | 25.1±3.5† | 0.073 |

| Compensated P-creatinine (µmol/l) | 102.2±42.1 | 95.6±35.0 | 110.1±48.3 | <0.0001 |

| Uncompensated P-creatinine (µmol/l) | 120.2±38.8 | 114.0±32.2 | 127.3±44.4 | <0.0001 |

| CG uncompensated P-creatinine (ml/min) | 44.2±14.8 | 39.8±13.2 | 49.5±15.0 | <0.001 |

| MDRD4 (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 59.6±20.7 | 55.3±19.4 | 64.7±21.0 | <0.001 |

Renal function estimates with different methods: CG and MDRD4. Divide by 88.4 to get creatinine concentration in mg/ml. Mean±SD, p<0.05 is regarded as significant.

*N=322.

†N=268.

BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CG, Cockcroft and Gault; MDRD4, modification of diet in renal disease equation 4

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistica (Statsoft, Tulsa). Analysis of variance was used to compare the difference in renal clearance in relation to age. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and SD.

Estimation of renal function and drug dosage

Plasma creatinine was analysed at the laboratory of Clinical Chemistry at Karolinska University Hospital and at the laboratory of Chemistry at Västerås hospital with a modified Jaffe method, traceable to IDMS27 and similar to an enzymatic method, that is, ‘compensated’ creatinine. These values have then been recalculated to ‘uncompensated’ creatinine when used in the CGold equation (uncompensated creatinine=compensated creatinine ×0.92+26) to resemble the CG results gained in the initial studies of dabigatran.13 28 In addition, we investigated if similar relation could be shown with two other older drugs with renal excretion; gabapentin and valaciclovir. Compensated creatinine has been incorporated in the MDRD4 equation (box 1). We then simulated the dabigatran, gabapentin, and valaciclovir doses, each participant would receive based on the resulting renal clearance. The eGFR is as usual given in relative value (ml/min/1.73 m2).

Box 1.

Estimations of renal function used in a cohort of elderly participants by two different equations: the Cockcroft-Gault (CG) equation with uncompensated P-creatinine (CGold) and the modification of diet in renal disease equation 4 (MDRD4) calculated with compensated creatinine traceable to isotope-dilution mass spectrometry. No correction factor for Afro-Americans has been included as all participants were Caucasians. P-creatinine concentration was calculated in µmol/l.

|

|

Results

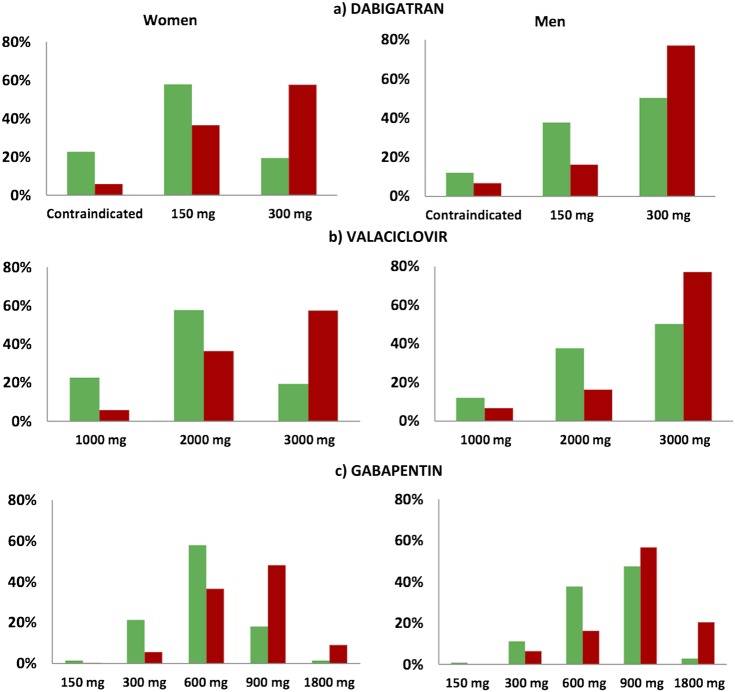

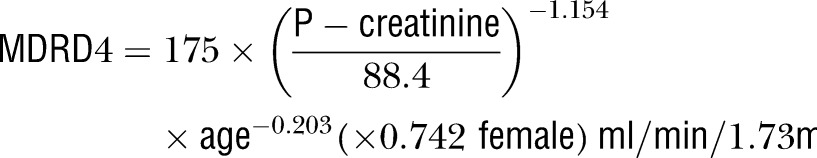

Renal function decreased significantly (p<0.001) in relation to increasing age for both estimations (figure 1). CGold produced the lowest estimated renal function, 44.2±14.8 ml/min, and MDRD4 the highest, 59.6±20.7 ml/min/1.73 m2 (p<0.001), the absolute mean difference being 13.5, 95% CI 12.9 to 14.2 (table 1). Data simulation showed a significantly higher mean dose of dabigatran with MDRD than with CGold: 260±76 mg compared with 208±103 mg (25% higher dose; p<0.001). The difference was even more pronounced for women, 253±73 mg for MDRD4 compared with 186±105 mg for CGold (+36%) and less for men, 267±77 mg for MDRD4 compared with 234±94 mg for CGold (+14%), but still highly significant (p<0.001). For women, the MDRD4 equation resulted in an increased dose compared with the CGold in 221 participants (51%), a lower dose in eight participants (2%) and an unaltered dose in 203 participants (47%). Dabigatran would be contraindicated (creatinine clearance less than 30 ml/min) in 18% of all participants using CGold and in 7% of those with the MDRD4 equation. In total, 33% of all participants would be recommended a full dose of dabigatran if CGold is used, whereas the corresponding number for MDRD4 is 67% (figure 2A). The same pattern was shown for valaciclovir and gabapentin; mean valaciclovir dose calculated with CGold was 2156±699 mg compared with 2602±603 mg with MDRD4 (21% higher dose; p<0.001). Gabapentin mean dose was 663±266 mg when calculated with CGold compared with 910±406 mg with the MDRD4 (+37%, p<0.001; figure 2B,C).

Figure 1.

Renal function estimated in 790 individuals aged 65 and older by the Cockcroft-Gault equation with uncompensated P-creatinine (creatinine clearance absolute values in ml/min) and modification of diet in renal disease equation 4 (MDRD4) calculated according to the equations in box 1. MDRD4 is given as a relative value (ml/min/1.73 m2; mean±SEM). Uncompensated creatinine denotes S/P-creatinine determined with the ‘old Jaffe’ method.13

Figure 2.

(A–C) Data simulation of recommended daily doses for dabigatran (A), valaciclovir (B) and gabapentin (C) in relation to renal function by the Cockcroft-Gault formula (green staples) and the abbreviated modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD4) formula (red staples) in 790 individuals aged 65 years and older in Sweden. Dose recommendations by the MDRD4 formula will result in significantly higher doses, particularly in women. As an example, 19% (82) of the female participants would receive an ordinary dose (300 mg) of dabigatran if the Cockcroft-Gault equation with uncompensated P-creatinine would be used when estimating renal function, compared to 59% (259) with the MDRD4 formula (A). Recommended daily dose for gabapentin is in general in a range 900–3600 mg if creatinine clearance is higher than 80 ml/min. We have chosen to show half of the maximum recommended dose in each stratum.

Discussion

Our study shows that the change from the CG equation with uncompensated P-creatinine by the Jaffe analysis method to the MDRD4 equation with a compensated creatinine traceable to IDMS, results in significantly higher renal function value in the elderly. Consequently, the dose recommendation based on MDRD4 results in higher doses of dabigatran, particularly in elderly female participants. This may have contributed to the serious and sometimes fatal ADRs reported around the world.4 6 29 30 We found similar results for two older renally excreted drugs (also developed during a period when uncompensated creatinine by the Jaffe creatinine method was used), valaciclovir and gabapentin for comparison.

The problem is similar to that which would be faced when treating patients with other renally excreted drugs (including metabolites), for example, antibiotics, pregabalin, metformin and morphine. Other researchers too have found similar results.15–17 31 There are reports suggesting that MDRD can be used for drug dosing,32 whereas others have questioned it.33–35

In Europe, a ‘Dear Healthcare Professional Letter’ was circulated in October 2011 to point out that renal function should be estimated in all patients before treatment with dabigatran. This recommendation was released to exclude those patients with creatinine clearance less than 30 ml/min, where dabigatran is contraindicated owing to increased risk of bleeding.36 Renal function should be re-estimated in clinical situations where renal function may decline and at least annually in patients older than 75 years (corresponding to 29% of all dabigatran users in Sweden). The current European dabigatran summary of products characteristics (SPCs) points out that in patients with advanced age and moderately impaired renal function (creatinine clearance 30–50 ml/min) dose reduction should be considered and the patients should be closely observed regarding bleeding or anaemia.37

Dose recommendations in relation to renal function given in the SPCs are in general based on endogenous creatinine clearance or estimated creatinine clearance according to the CG equation (including P-creatinine, age, sex and weight) in ml/min, an absolute value of clearance.1 This is also the case for dabigatran.38 However, different equations have been used in the trials such as the CG equation,39–41 the original MDRD equation,7 9 measured creatinine clearance and sinistrin clearance.26 In one study only creatinine clearance was mentioned, without stating the clearance estimation method.41 Since then, worldwide standardisation of the creatinine method has resulted in a lower reference range for creatinine and thus higher clearance values in patients with low P-creatinine, for example, elderly patients. Other researchers have also pointed out the differences among results from the various methods to estimate renal function and the consequential differences in doses.15 17 31 42

The ‘Dear Healthcare Professional Letter’ states that dose recommendations should be based on equations based on sex, age and weight.36 This statement excludes the MDRD4 equation and the CKD-Epi equation as they do not include weight in the calculation. With MDRD4 (we found similar results with the CKD-Epi formula—data not shown) more patients will be recommended higher doses of dabigatran than with CG and will be exposed to greater risk of dose-concentration-dependent ADRs, for example, haemorrhage. There is no antidote to give if the dose is too high, nor in trauma or during acute operations. The only treatment available presently is symptomatic or possibly dialysis.43

Another important factor is to use the patient's absolute renal function and not the relative clearance the patient or participant would have had if his/her body surface area (BSA) would have been 1.73 m2 since most dose recommendations based on dose–effect studies use the absolute clearance.34 ‘Absolute’ = without correction for BSA (ml/min) and ‘relative’=with correction for BSA (ml/min/1.73 m2). In most patients, the difference between the two may be small but in certain patients, for example, elderly women, in particular those with a BSA smaller than (the standard) 1.73 m2, the difference may be considerable. A case report from France describes two elderly dabigatran-treated women 84 and 89 years old, respectively, one with a fatal and one with a serious haemorrhage. Plasma concentrations of dabigatran were reported to be high. Both patients had low weight, low relative creatinine clearance of 29 and 32 ml/min/1.73 m2, respectively, and probably an absolute creatinine clearance below 30 ml/min, which is a contraindication for dabigatran treatment.4

For older remedies to prevent dangerously high doses in the elderly a comparison factor between older and newer methods to determine P-creatinine may be needed, however impractical. We found that the method used to estimate renal function has impact on recommended dabigatran doses in the elderly. Subsequently, one question remains to be answered: Can we rely on the measurements of renal function made in the initial dabigatran pharmacokinetic studies? This needs to be elucidated urgently for the elderly.

Elderly patients with decreased renal function are at particular risk for dose-dependent and concentration-dependent ADRs. Their reduced renal function is not always noticed.18 There is a great need of evidence-based support when prescribing drugs for elderly patients.44 Before new methods to estimate renal function, for example, MDRD4 and CKD-Epi, all being surrogate markers for renal function, are used for drug dosing in the elderly, the consequences must be well documented including pharmacokinetic modelling and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). In the most recent draft guideline from the US FDA, both CG and MDRD4 may be used.1 The current ‘guidance on the evaluation of the pharmacokinetics of medicinal products in patients with impaired renal function’ from European Medicines Agency 2004 (EMEA 2004) states that measuring GFR should be based on accurate well established methods (such as iohexol clearance).45 In contrast to the US FDA, there is no practical recommendation from EMEA.

We support that recommended dabigatran dose-rate should be adjusted linearly for decrease in creatinine clearance and standard pharmacological principles.46 We also suggest that the therapy in the elderly is more frequently guided by TDM, if available.

Conclusion

This data simulation study shows that the MDRD4 equation would result in higher doses of dabigatran, gabapentin, and valaciclovir to elderly participants, particularly in women, compared to the CG equation that was used during the clinical trials, and thus increase the risk of dose-dependent and concentration-dependent ADRs. Although dose recommendations for dabigatran in the SPCs refer to both renal function and age, creatinine clearance according to CG is the basis for calculating recommended doses for dabigatran as for many other drugs with renal elimination. Doses based on other methods may be associated with considerable risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Maria Hentschke, RN, for her skillful contribution with the collection of patient data, and to Professor Gideon Koren, who provided valuable comments to the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: AH, IOC and UB initiated, designed and analysed the data and wrote the article. GN, SS, AS, MVE, GÖ contributed with the collection and evaluation of patient data. All authors interpreted the data, critically revised the manuscript and gave the final approval of the version to be published. AH is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by the Stockholm County Council (ALF 20060747, FOU project no. 560747) and by grants from the Karolinska Institutet.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: All studies, except one study, had ethics approval. However, all personal data were blinded for the researchers and we could therefore not connect the results to participants. This has been stated in the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Guidance for industry pharmacokinetics in patients with impaired renal function—study design, data analysis, and impact on dosing and labeling. 2010. Draft guidance. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM204959.pdf (accessed 3 Feb 2012)

- 2.Pradaxa, SPC. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2012/05/WC500127777.pdf (accessed 3 Apr 2013)

- 3.Casado Naranjo I, Portilla-Cuenca J, Jiménez Caballero P, et al. Fatal intracerebral hemorrhage associated with administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in a stroke patient on treatment with dabigatran. Cerebrovasc Dis 2011;32:616–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legrand M, Mateo J, Aribaud A, et al. The use of dabigatran in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1285–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen B, Viny A, Garlich F, et al. Hemorrhagic complications associated with dabigatran use. Clin Toxicol 2012;50:854–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food and Drug Administration http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm282724.htm (accessed 3 Feb 2012).

- 7.Ezekowitz MD, Reilly PA, Nehmiz G, et al. Dabigatran with or without concomitant aspirin compared with warfarin alone in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (PETRO Study). Am J Cardiol 2007;100:1419–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976;16:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:461–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:247–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wuyts B, Bernard D, Van den Noortgate N, et al. Reevaluation of formulas for predicting creatinine clearance in adults and children, using compensated creatinine methods. Clin Chem 2003;49:1011–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan MH, Ng KF, Szeto CC, et al. Effect of a compensated Jaffe creatinine method on the estimation of glomerular filtration rate. Ann Clin Biochem 2004;41:482–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delanghe J, Speeckaert M. Creatinine determination according to Jaffe—what does it stand for? NDT Plus 2011;4:83–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyman HA, Dowling TC, Hudson JQ, et al. Comparative evaluation of the Cockcroft-Gault Equation and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation for drug dosing: an opinion of the Nephrology Practice and Research Network of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy 2011;31:1130–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gouin-Thibault I, Pautas E, Mahé I, et al. Is Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula similar to Cockcroft-Gault formula to assess renal function in elderly hospitalized patients treated with low-molecular-weight heparin? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007;62:1300–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill J, Malyuk R, Djurdjev O, et al. Use of GFR equations to adjust drug doses in an elderly multi-ethnic group—a cautionary tale. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:2894–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helldén A, Bergman U, Von Euler M, et al. Adverse drug reactions and impaired renal function in elderly patients admitted to the emergency department: a retrospective study. Drugs Aging 2009;26:595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank M, Guarino-Gubler S, Burnier M, et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate in hospitalised patients: are we overestimating renal function? Swiss Med Wkly 2012;142:1–11 doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helldén A, Odar-Cederlöf I, Diener P, et al. High serum concentrations of the acyclovir main metabolite 9-carboxymethoxymethylguanine in renal failure patients with acyclovir-related neuropsychiatric side effects: an observational study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003;18:1135–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Söderström A, Bergman U, Helldén A, et al. Renal function and drug treatment in a home care center in Farsta (Abstract. In Swedish). Poster LÄ 2P at the General Meeting of the Swedish Society of Medicine, Gothenburg, Hygiea, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson M, Bergman U, Helldén A, et al. Adverse drug reaction-related admissions at the Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge—a follow up with focus on generic drug treatment. (Abstract. In Swedish) Poster AM25P at the General Meeting of the Swedish Society of Medicine, Gothenburg, Hygiea, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odar-Cederlöf I, Oskarsson P, Öhlén G, et al. Adverse drug effect as cause of hospital admission. Common drugs are the major part according to the cross-sectional study (in Swedish). Läkartidningen 2008;105:890–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Von Euler M, Eliasson E, Öhlén G, et al. Adverse drug reactions causing hospitalization can be monitored from computerized medical records and thereby indicate the quality of drug utilization. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:179–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson G, Hedberg P, Öhrvik J. Survival of the fattest: unexpected findings about hyperglycaemia and obesity in a population based study of 75-year-olds. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000012. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, et al. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet 2010;49:259–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Expressing the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate with standardized serum creatinine values. Clin Chem 2007;53:766–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb EJ. Effect of a compensated Jaffe creatinine method on the estimation of glomerular filtration rate. Ann Clin Biochem 2005;42:160–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dabigatran (Pradaxa): risk of bleeding relating to use. http://www.tga.gov.au/safety/alerts-medicine-dabigatran-111005.htm (accessed 10 Jan 2012).

- 30.Wychowski MK, Kouides PA. Dabigatran-induced gastrointestinal bleeding in an elderly patient with moderate renal impairment. Ann Pharmacother 2012;46:e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denetclaw TH, Oshima N, Dowling TC. Dofetilide dose calculation errors in elderly associated with use of the modification of diet in renal disease equation. Ann Pharmacother 2011;45:e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens L, Nolin T, Richardson M, et al. Comparison of drug dosing recommendations based on measured GFR and kidney function estimating equations. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;54:33–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wargo K, Eiland E3, Hamm W, et al. Comparison of the modification of diet in renal disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations for antimicrobial dosage adjustments. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1248–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spruill WJ, Wade WE, Cobb HH. Continuing the use of the Cockcroft-Gault equation for drug dosing in patients with impaired renal function. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;86:468–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermsen E, Maiefski M, Florescu M, et al. Comparison of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations for dosing antimicrobials. Pharmacotherapy 2009;29:649–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/pl-p/documents/websiteresources/con134763.pdf (accessed 20 Mar 2012).

- 37.Dabigatran SPC. http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/20760/SPC/ (accessed 13 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pradaxa EPAR—product information. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000829/WC500041059.pdf (accessed 13 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eriksson BI, Dahl OE, Ahnfelt L, et al. Dose escalating safety study of a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran etexilate, in patients undergoing total hip replacement: BISTRO I. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:1573–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trocóniz I, Tillmann C, Liesenfeld K, et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of the new oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate (BIBR 1048) in patients undergoing primary elective total hip replacement surgery. J Clin Pharmacol 2007;47:371–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehr T, Haertter S, Liesenfeld KH, et al. Dabigatran etexilate in atrial fibrillation patients with severe renal impairment: dose identification using pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation. J Clin Pharmacol 2012;52:1373–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charhon N, Neely MN, Bourguignon L, et al. Comparison of four renal function estimation equations for pharmacokinetic modeling of gentamicin in geriatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:1862–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cotton BA, McCarthy JJ, Holcomb JB. Acutely injured patients on dabigatran. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2039–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tawadrous D, Shariff SZ, Haynes RB, et al. Use of clinical decision support systems for kidney-related drug prescribing: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;58:903–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Note for guidance on the evaluation of the pharmacokinetics of medicinal products in patients with impaired renal function. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003123.pdf (accessed 31 Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chin PK, Vella-Brincat JW, Barclay ML, et al. Perspective on dabigatran etexilate dosing—why not follow standard pharmacological principles? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;74:734–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.