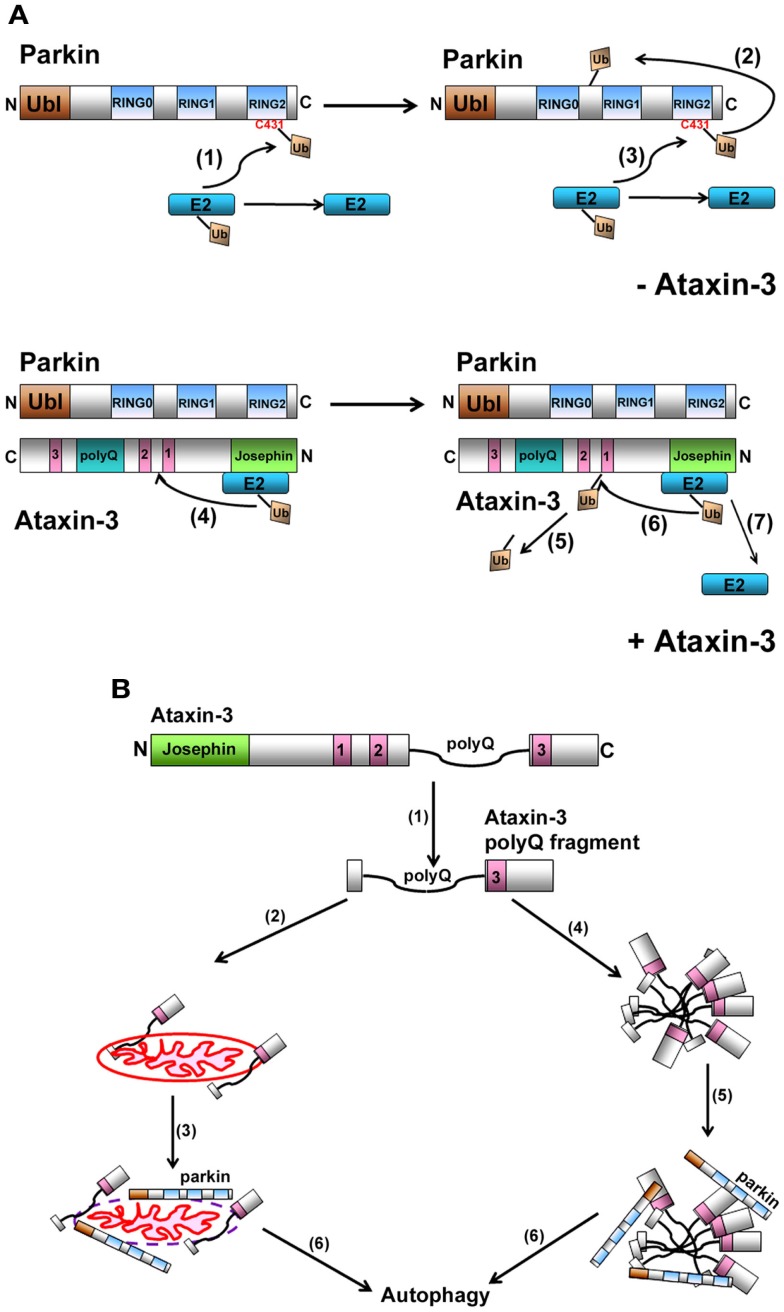

Figure 2.

(A) Model representation of how ataxin-3-mediated deubiquitination regulates parkin self-ubiquitination. When parkin ubiquitinates itself, the charged E2-Ub thioester transfers the Ub onto C431 in parkin to form a transient parkin-Ub thioester complex (1). Parkin now transfers this Ub onto one of its own lysines generating an isopeptide linkage (2). Following the transfer of Ub onto itself, parkin is now free to receive a new Ub and this continues the cycle of parkin self-ubiquitination (3). When ataxin-3 is present, we propose that ataxin-3, through its interaction with the IBR-RING2 domain of parkin, blocks the C431 residue, impeding parkin from forming a parkin-Ub thioester. Instead, ataxin-3 now interacts with the E2, directing the transfer of Ub onto a lysine within ataxin-3 (4). This isopeptide linkage is transient as ataxin-3 can catalyze its removal (5) (unpublished data), allowing ataxin-3 to repeat this cycle of self-ubiquitination/deubiquitination, thereby reducing the ability of parkin to ubiquitinate itself (6 and 7). (B) Proposed model for how the expanded ataxin-3 can promote the autophagic clearance of parkin. In the presence of calcium, calpains cleave full-length ataxin-3, generating fragments containing the expanded polyQ tract (1). These fragments can associate with mitochondria (2), causing mitochondrial damage, parkin recruitment (3), and ultimately parkin-mediated clearance of itself and the mitochondria via the autophagy pathway (6). Alternatively, these expanded polyQ fragments also have a propensity to aggregate (4), recruiting parkin and CHIP (5), which now act to direct these aggregates and themselves for autophagic clearance (6).