Abstract

Objective

Reduced nephron number is hypothesized to be a risk factor for chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Whether reduced nephron number accelerates the early stages of diabetic nephropathy is unknown. This study asked whether the rate of development of diabetic nephropathy lesions was different in type 1 diabetic (T1DM) patients with a single (transplanted) kidney compared to patients with two (native) kidneys.

Research Design and Methods

Three groups of volunteers were studied: 28 T1DM kidney transplant recipients with 8–20 years of good graft function, 39 two-kidney patients with duration of T1DM matched to the time since transplant in the one-kidney group, and 30 age-matched normal controls. Electron microscopic morphometry was used to estimate glomerular structural parameters on 3.0±1.4 glomeruli per biopsy.

Results

Higher in the one vs. two-kidney diabetic groups, respectively, were serum creatinine (1.3±0.4 vs. 0.9±0.2 mg/dl, p<0.001), systolic blood pressure (133±13 vs. 122±11 mmHg, p<0.001) and albumin excretion rate [32.1(2–622) vs. 6.8(2–1,495) μg/min, p=0.006]. There were no differences in the one vs. two-kidney diabetic groups, respectively, in glomerular basement membrane width [511(308–745) vs. 473(331–814) nm], mesangial fractional volume (0.30±0.06 vs. 0.27±0.07), mesangial matrix fractional volume (0.16±0.05 vs. 0.16±0.06), and mesangial matrix fractional volume per total mesangium (0.16±0.07 vs. 0.64±0.09). However, these glomerular structural parameters were statistically significant higher in both diabetic groups compared to normal controls. Results were similar when patients receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were excluded from the analyses.

Conclusions

Reduced nephron number is not associated with accelerated development of diabetic glomerulopathy lesions in T1DM patients.

INTRODUCTION

Decreased nephron number at birth has been proposed as a risk factor for the development of chronic kidney disease and hypertension (1, 2). Oligomeganephronia, representing an early developmental defect of ureteric bud morphogenesis, which results in decreasing nephron number to approximately one-fifth of normal, is associated initially only with glomerular and tubular hypertrophy (3). Ultimately these patients manifest proteinuria, hypertension, declining glomerular filtration rate, and progress to end-stage kidney disease over a period of 10 to 12 years (4). This course, in many ways, is mimicked by the remnant kidney model in rats (5). The impact of lesser reduction in nephron number on human disease is less clear. Children born with a single kidney followed for 7–40 years, however, do not appear to be at increase risk for hypertension or renal disease (6). Living kidney donors, moreover, have little or no increase in risk of long-term adverse consequences to their remaining normal kidney (7–9). This suggests that the association of primary hypertension with reduced nephron number (2) is due to factors other than nephron number alone.

Reduced nephron number has been proposed as a risk factor and is implicated in association with diabetic nephropathy in humans (10), but direct studies so far have been unavailable. This present study addresses the question whether reduced nephron number, decreased by approximately one-half, accelerates the early lesions of diabetic nephropathy, by comparing the rate of development of glomerular lesions in kidneys exposed to the diabetic state for 8–20 years in patients with one transplanted kidney vs. two native kidneys.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Transplant (One-Kidney) Group

Twenty-eight type 1 diabetic patients were studied. Twenty-five received living related donor kidneys (eight were HLA identical), while 3 patients had cadaveric kidney transplants. All patients with at least 8 years of good graft function, serum creatinine ≤ 2.5 mg/dl, and adequate renal tissue for study were included. These patients had volunteered for studies of diabetic nephropathy recurrence in the renal allograft at University of Minnesota, and had their research renal biopsies performed between 1977 and 2000. All had received their renal transplant between 1969 and 1987. None had received a pancreas transplant. At the time of renal biopsy, 8 patients were on cyclosporine (CsA), azathioprine (AZA), and prednisone; 3 on CsA and prednisone; 13 on AZA and prednisone; 1 on CsA and AZA; 1 on AZA; 1 on CsA; and 1 on mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Six patients were receiving angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and no patient was on angiotensin type II receptor blockers (ARB). All studies were approved by the Committee for the Use of Human Subjects in Research at the University of Minnesota.

Two-Kidney Group

Thirty-nine type 1 diabetic patients who had research kidney biopsies constituted the two-kidney group. Thirteen had volunteered for the Natural History Study of Nephropathy in Type 1 Diabetes (11–13), 12 were in studies of diabetic nephropathy in sibling pairs (14, 15), and 14 were being evaluated for consideration of pancreas transplantation. All patients had at least 8 years of diabetes duration and serum creatinine ≤2.0 mg/dl and/or glomerular filtration rate ≥45 ml/min/1.73m2. Two patients were on ACE inhibitors; no patients were on ARBs.

Duration was defined as time from onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus to renal biopsy in the two-kidney group, and time since transplant for the one-kidney group. Patients in the two-kidney group were matched for duration (8.5–23.6 years) with that in the one-kidney group (8.0–20.2 years). The two and one-kidney groups were also matched, where possible, for kidney gender. Research kidney biopsies were only performed in transplant group subjects with serum creatinine ≤ 2.5 mg/dl, to include patients with well functioning renal allograft. Based on our experiences, patients with serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dl would have many sclerosed glomeruli, often precluding electron microscopy measurements, Serum creatinine < 2.0 mg/dl was selected as cut-off point in the two-kidney group for the same reason.

Controls were 30 normal living kidney donors matched for age (33.3±7.7 years) and gender (15 female) with the two-kidney group.

Clinical Studies

All patients were admitted for 2–3 days to the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at the University of Minnesota for research renal biopsy and renal function studies. Trained nurses measured blood pressure using an oscillometric automatic monitor. The mean values of multiple GCRC measurements were used for deriving the systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressures. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure levels ≥ 140/90 mmHg or the use of antihypertensive medications. Three patients from the one-kidney group did not have available blood pressure data. Glycosylated hemoglobin was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. Two patients from the one-kidney and three from the two-kidney group did not have available glycosylated hemoglobin data. Serum creatinine was measured by an automated method using the Jaffe reaction. Urinary albumin excretion was assessed from at least one, but usually two 24-hour sterile GCRC urine collections by fluorometric assay. Four patients in the one-kidney group did not have urinary albumin excretion measurements available.

Renal Biopsy Morphometric Studies

Renal tissues obtained by percutaneous biopsy in the diabetic groups were processed for electron microscopy as previously described (16, 17). Controls had intra-operative kidney biopsies performed prior to removal of their donated kidney. Stained 1 μm thick sections were used to select the centermost, non-sclerotic glomerulus in the block for study. All tissues were masked prior to study. 3.0±1.4 (range 1–7) non-sclerotic glomeruli per biopsy were photographed with a JEOL 100CX electron microscopy at a final magnification of 3,900× to produced photomontages of the entire glomerular profile. Montages from all patients in the one and two-kidney groups were blindly screened for changes consistent with transplant glomerulopathy (18–21). Cases where transplant glomerulopathy was suspected were excluded.

The electron microscopic photomontages were used to estimated mesangial fractional volume [Vv(Mes/glom)] by counting the number of fine points falling on mesangium in relation to the number of coarse points hitting the glomerular tuft (11, 16, 17). More than 100 course points were counted per each biopsy. Similar methods were used to estimated the mesangial matrix fractional volume [Vv(MM/glom)], as well as mesangial cell fractional volume [Vv(MC/glom)] by counting fine points falling on mesangial matrix and on mesangial cell respectively (17). The mesangial matrix fractional volume per total mesangium [Vv(MM/mes)] was calculated as ratio of mesangial matrix to total mesangium (mesangial matrix and mesangial cell), or Vv(MM/glom)/[Vv(MM/glom) + Vv(MC/glom)] (22). Another set of random systemic images of glomeruli taken at ×12,000 magnification and representing approximately 15–20% of the glomerular cross section were used to measure glomerular basement membrane (GBM) width. Using the orthogonal intercept method, GBM width was estimated using a systematic and unbiased method (23) to measure at least 80 sites along the GBM per biopsy: 145±47 in the one-kidney group, and 149±39 in the two-kidney group.

Statistics Analysis

We used SPSS programs for Windows for the statistical analyses (version 12.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, except for urinary albumin excretion and GBM width that were expressed as median (range) and logarithmically transformed prior to analysis. Clinical parameters in the one vs. the two-kidney groups were compared using unpaired independent t-tests. ANOVA, followed by least significant difference post-hoc test was used to compare the structural parameters among one-kidney, two-kidney and the control groups. Chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables. Because of the possibility that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors could modify the natural history of diabetic nephropathy lesions, clinical data and glomerular structural parameters were analyzed once more after excluding patients treated with ACE inhibitor. Partial correlations were performed between glomerular structural variables and diabetes duration, while controlling for the effect of glycemia. Two-sided P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics

Gender and duration of exposure of the kidneys to type 1 diabetes mellitus were, by design, similar in the two diabetic groups, while kidney age and patient age were greater at the time of kidney biopsy in the one-kidney patients (Table 1). Systolic blood pressure, serum creatinine, and urinary albumin excretion were higher in the one-kidney group. Glycosylated hemoglobin was comparable in the two diabetic groups (Table 1). All but one of the group comparisons was similar when patients on ACE inhibitor at the time of study were excluded from the analyses. Kidney age, with these exclusions, was no longer statistically different among the groups.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Subjects

| One-Kidney | Two-Kidneys | Controls | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 28 | 39 | 30 | |

| Kidney gender (n) | ||||

| Female | 13 | 22 | 15 | NA |

| Male | 15 | 17 | 15 | |

| Patient age (years) | 49 ± 8 | 32 ± 9 | 33 ± 8 | < 0.001 |

| Kidney age (years) | 38 ± 13 | 32± 9 | 33 ± 8 | 0.048 |

| Diabetes duration (years)* | 13 ± 4 | 14 ± 3 | NA | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Systolic | 133 ± 13† | 122 ± 11 | < 0.001 | |

| Diastolic | 73 ± 8† | 74 ± 8 | NS | |

| Hypertension (n) | 22 | 7 | < 0.001 | |

| On ACE inhibitor (n) | 6 | 2 | ||

| Glycosylated hemoglobin (%)‡ | 8.4 ± 1.1 | 9.0 ± 1.8 | NS | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.2§ | < 0.001 | |

| Urinary albumin excretion (μg/min)|| | 32.1 (2–622) | 6.8 (2–1,495) | 0.006 | |

| Renal Transplantation (n) | ||||

| Living | 25 | |||

| Cadaver | 3 | |||

| On Cyclosporine (n) | 13 | |||

Results of continuous variables are mean ± SD or median (range).

Diabetes duration in the one-kidney group is defined as the duration from kidney transplant to kidney biopsy, in two-kidneys group it is defined as the duration from type 1 diabetes onset to kidney biopsy.

Blood pressure measurements were available in 25 patients.

Glycosylated hemoglobin was available in 26 patients from the one-kidney group and in 36 patients from the two-kidneys group.

Serum creatinine was available in 37 patients.

Urinary albumin excretion was available in 24 patients from the one-kidney group and was logarithmic transformed prior to statistical analysis.

Abbreviations: not applicable (NA), not significant (NS), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE).

Morphometric Findings

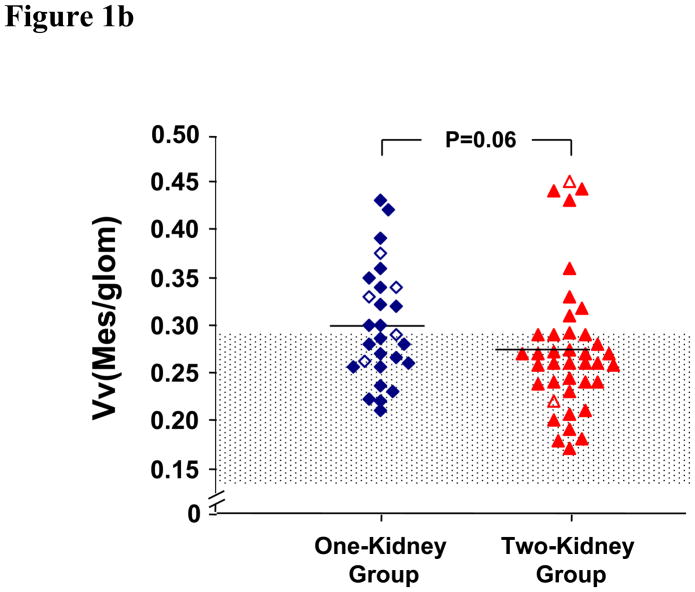

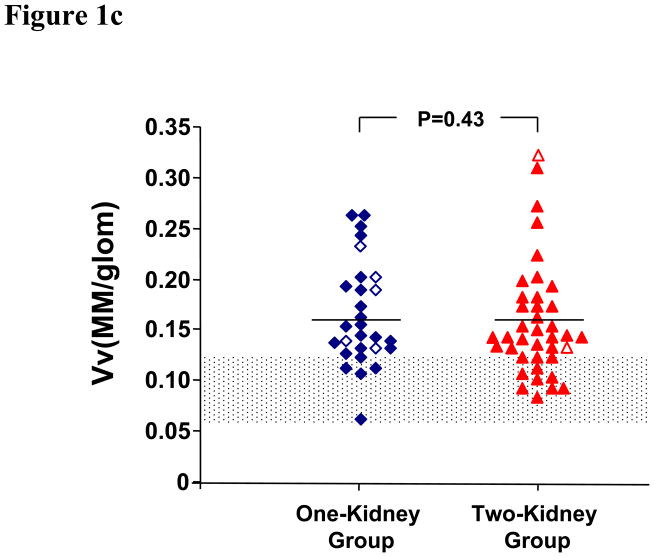

GBM width, Vv(Mes/glom), Vv(MM/glom), and Vv(MM/mes) in the one-kidney group were not different from those in the two-kidney group (Table 2 and Figures 1a–d). These glomerular structural parameters were greater in the diabetic groups than in the normal controls. Vv(MC/glom) was greater in the one-kidney group than in the two-kidney and the control groups (Table 2 and Figure 1e).

TABLE 2.

Glomerular Structural Parameters

| One-Kidney | Two-Kidneys | Controls | ANOVA P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 28 | 39 | 30 | |

| GBM width (nm) | 511 (308–745)† | 473 (331–814) | 314 (250–479)‡ | < 0.001* |

| Vv(Mes/glom) | 0.30±0.06§ | 0.27±0.07 | 0.20±0.04‡ | < 0.001 |

| Vv(MM/glom) | 0.16±0.05† | 0.16±0.06 | 0.09±0.02‡ | < 0.001 |

| Vv(MC/glom) | 0.10±0.02|| | 0.09±0.02 | 0.09±0.02¶ | 0.015 |

| Vv(MM/Mes) | 0.61±0.07† | 0.64±0.09 | 0.51±0.06‡ | < 0.001 |

Results of continuous variables are mean ± SD or median (range).

Denotes log transformation of nonparametric variables prior to statistical analysis.

P=NS comparing one-kidney vs. two-kidney groups.

P<0.0001 comparing one-kidney group vs. controls, as well as two-kidney group vs. controls.

P=NS (0.082) comparing one-kidney vs. two-kidney groups.

P=0.005 comparing one-kidney vs. two-kidney groups.

P=0.03 comparing one-kidney group vs. controls, P=NS comparing two-kidney group vs. controls.

Abbreviations are glomerular basement membrane (GBM), mesangial fractional volume [Vv(Mes/glom)], mesangial matrix fractional volume [Vv(MM)/glom], mesangial cell fractional volume [Vv(MC/glom)], mesangial matrix fractional volume per total mesangium [Vv(MM/mes)].

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Glomerular Basement Membrane Width. One-kidney patients are shown with (◇) and without (◆) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy, and two-kidney patients with (Δ) and without (▲) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The shaded area is 5% and 95% confidence interval for the control.

Figure 1b. Mesangial Fractional Volume. One-kidney patients are shown with (◇) and without (◆) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy, and two-kidney patients with (Δ) and without (▲)angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The shaded area is mean ± 2SD for the control.

Figure 1c. Mesangial Matrix Fractional Volume. One-kidney patient are shown with (◇) and without (◆) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy, and two-kidney patients with (Δ) and without (▲) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The shaded area is mean ± 2SD for the control.

Figure 1d. Mesangial Cell Fractional Volume. One-kidney patients are shown with (◇) and without (◆) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy, and two-kidney patients with (Δ) and without (▲) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The shaded area is mean ± 2SD for the control.

Figure 1e. Mesangial Matrix Fractional Volume per Total Mesangium. One-kidney patients are shown with (◇) and without (◆) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy, and two-kidney patients with (Δ) and without (▲) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The shaded area is mean ± 2SD for the control.

Similar results were obtained when patients on ACE inhibitors were excluded from the analyses. However, Vv(MC/glom) was no longer statistically significant different from controls (Table 3 and Figure 1e).

TABLE 3.

Glomerular Structural Parameters Excluding Patients on Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

| One-Kidney | Two-Kidneys | Controls | ANOVA P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 22 | 37 | 30 | |

| GBM width (nm) | 489 (308–745)† | 473 (331–814) | 314 (250–479)‡ | < 0.001* |

| Vv(Mes/glom) | 0.30±0.06† | 0.27±0.07 | 0.20±0.04‡ | < 0.001 |

| Vv(MM/glom) | 0.16±0.06† | 0.16±0.06 | 0.09±0.02‡ | < 0.001 |

| Vv(MC/glom) | 0.10±0.02§ | 0.09±0.02 | 0.09±0.02|| | NS |

| Vv(MM/Mes) | 0.61±0.06† | 0.64±0.09 | 0.51±0.06‡ | < 0.001 |

Results of continuous variables are mean ± SD or median (range).

Denotes log transformation of nonparametric variables prior to statistical analysis.

P=NS comparing one-kidney vs. two-kidney groups.

P<0.0001 comparing one-kidney group vs. controls, as well as two-kidney group vs. controls.

P=0.03 comparing one-kidney vs. two-kidney groups.

P=NS comparing one-kidney group vs. controls, P=NS comparing two-kidney group vs. controls.

Abbreviations are glomerular basement membrane (GBM), mesangial fractional volume [Vv(Mes/glom)], mesangial matrix fractional volume [Vv(MM)/glom], mesangial cell fractional volume [Vv(MC/glom)], mesangial matrix fractional volume per total mesangium [Vv(MM/mes)], not significant (NS).

Adjusted for glycemia, both Vv(MM/glom) and Vv(Mes/glom) were correlated with duration of type 1 diabetes mellitus from onset to renal biopsy in the two-kidney patients not treated with ACE inhibitors (r=0.43, p=0.013 and r=0.39, p=0.026; respectively). The relationships in the total two-kidney cohort [r=0.35, p=0.042 for Vv (MM/glom); and r=0.32, p=0.059 for Vv(Mes/glom)] were weaker. There were no statistically significant correlations between glomerular structural parameters and duration expressed either as time from onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus to transplant or time from transplant to renal biopsy in the one-kidney patients.

DISCUSSION

This study, using quantitative unbiased morphometric techniques, evaluated the role of nephron number in the rate of development of early diabetic nephropathy lesions in type 1 diabetic patients. Given that kidney transplant patients have a one compared to two kidneys in the non-transplant patients creates two groups where nephron number is, on average, twice as high in the two-kidney group. This design obviates the need for counting nephrons in order to create groups that are markedly different for this parameter.

Diabetic nephropathy lesions can reoccur in the renal allograft (24–30). The incidence of recurrent clinical allograft diabetic nephropathy in transplant kidney biopsy samples ranges from 0.4 to 1.8% (26–30). Early pathologic lesions in allograft diabetic nephropathy follow a course similar to native diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetic patients. Thickening of glomerular basement membrane and increase in mesangial fractional volume has been described 2–10 years (25, 30–32) after kidney transplant. Light microscopic studies have shown that the rate of development of diabetic nephropathy lesions in the transplanted kidney is highly variable, ranging from minimal changes over many years to relatively advanced changes leading to allograft failure has been reported in as early as 8 years post-transplant (32), and mostly occur in the second decade post-transplant (26). The major cause of allograft loss in diabetic transplant recipients is chronic allograft nephropathy, death or acute rejection. Recurrent and de novo allograft diabetic nephropathy are rarely documented as a cause of allograft end stage renal disease. The initial studies of allograft diabetic nephropathy suggested that this variability in the rate of development of diabetic nephropathy in the renal allograft can only partially be explained by glycemia (30) and hypothesized that variability in the intrinsic responses of the renal transplant tissues to the diabetic state could be an important explanatory factor. This early work did not suggest that the rate to diabetic nephropathy lesions development in type 1 diabetic patients was faster than in patients with two native kidneys (24). However, the imprecision of the light microscopy methods used in these studies do not allow confidence in the conclusion that reduced nephron number was not associated with acceleration of diabetic nephropathy lesions.

Other histopathologic findings of allograft diabetic nephropathy such as tubulointersitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, hyaline arterial thickening can also be present in other forms of allograft dysfunction including transplant glomerulopathy, chronic cyclosporine toxicity, chronic rejection, hypertension, or related to aging effect. Those histopathology features were not studied due to the non-specificity and overlapping features with allograft diabetic nephropathy.

Previous studies addressing the question of nephron number as a risk factor for early diabetic nephropathy lesions were generally based on extrapolations from birth weight and height regarding nephron number endowment (10, 33). A single study with careful glomerular counting using unbiased stereological method in 25 type 1 diabetic patients and 39 type 2 diabetic patients found no difference in glomerular number between patients with overt diabetic nephropathy and normal controls (34). The present study is also consistent with the finding that birth weight, a correlate of nephron number (35, 36), is not a predictor of diabetic nephropathy rate.

As expected, the one-kidney patients were older than the two-kidney patients. Serum creatinine was higher in the one-kidney group, not surprisingly considering that these were single kidney patients and that 46% of the one-kidney patients were receiving cyclosporine. The one-kidney patients had higher systolic blood pressure, and a greater incidence of hypertension. This could be related to prednisone, cyclosporine therapy, or the presence of diseased native kidneys. The greater urinary albumin excretion in the one-kidney group may not reflect diabetic nephropathy in the renal allograft alone, since albuminuria may also have emanated from the diseased native kidneys and not all kidney transplant recipients had native nephrectomy.

GBM width and mesangial fractional volume were greater in both diabetic groups than in the control group indicating that diabetic lesions were developing in both one and two-kidney groups. This is consistent with previous reports of recurrence of diabetic glomerular lesions in the renal allograft (37). The mesangial matrix fractional volume per glomerulus and the mesangial matrix fractional volume per total mesangium were greater in the diabetic patient groups than in the control group, but not different in the one compared to the two-kidney group. Accumulation of the mesangial matrix is a major component of diabetic glomerulopathy (38). These changes are, in fact, characteristic of diabetes, and different from those seen in other diseases. For example, in type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, the dominant cause of mesangial expansion is accumulation of mesangial cellular compartment (22). If, in fact, the mesangial matrix increase in the one-kidney patients were attributable to the chronic allograft nephropathy, this would be a further argument against acceleration of diabetic nephropathy lesions in patients with reduced nephron number. Glomeruli were carefully screened, however, to avoid the inclusion of patients with transplant glomerulopathy in this study.

The slight, but statistically significant increase in mesangial cell fractional volume in the one-kidney patients, compared to the two-kidney patients and normal controls, is unexplained. This may be the consequence of subtle allograft changes related to transplantation per se. However, similar and also unexplained group differences in Vv(MC/glom) were seen between different centers in a type 1 diabetic nephropathy natural history study (11). The biological significance of this subtle structural difference is likely to be very small.

An important underlying assumption in the comparison of the one and the two-kidney groups is that the kidney transplanted into the diabetic environment has the same likelihood to have risk of or protection from the development of diabetic nephropathy as the general population of diabetic patients. This assumption could be wrong on at least three accounts. Firstly, the risk of diabetic nephropathy may not be totally intrinsic to the local tissue responses to the diabetic state, but may also be related to systemic factors which could be more prominent among the one-kidney patients, who, by definition, have all demonstrated their susceptibility to severe diabetic nephropathy. Secondly, the majority of one-kidney patients received living-related donor kidneys. It is possible that diabetic nephropathy susceptibility genes are more common in these related donors than in the general population. Thirdly, the one-kidney patients had higher systolic blood pressure and a greater incidence of hypertension. At any rate, these possibilities, if true, might have been expected to be associated with accelerated lesion development in the one-kidney group, and this was not found.

On the other hand, albeit it uncommon, undiagnosed allograft renal artery stenosis may have provided some protection from diabetic nephropathy to the transplanted kidney (39, 40). Immunosuppressive drugs could also suppress inflammatory processes possibly altering the development of diabetic nephropathy, but there is little direct data linking the lesions studied here with inflammatory processes.

The one-kidney patients had excellent overall graft function considering the mean post-transplant time of 13 years. Thus, it did not appear that the recurrence of diabetic nephropathy lesions in these patients was associated with progressive graft dysfunction and accelerated graft loss 8 to 20 years post-transplant. This could be due to selection bias since one-kidney patients with serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dl were excluded from these studies. However, as noted above, diabetic nephropathy, per se, is an uncommon cause of graft failure in the first decades following renal transplantation (26).

This study found that early diabetic nephropathy lesions occurring in the renal transplant are not different from that in the native kidneys of patients with type 1 diabetes. These results argue that reduced nephron number is not a major risk factor for development of early diabetic glomerular lesions. However, it is quite possible that reduced nephron number could be associated with accelerated progression from overt diabetic nephropathy to terminal uremia.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants DK13083 and DK07087 from the National Institutes of Health, and M01-RR00400 from the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Chang’s pediatric renal research fellowship was supported by a pre-faculty Training grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Caramori was a research fellow of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International (JDRFI) and is currently a JDRFI Career Development Award recipient. We are indebted to John Basgen and Tom Groppoli for performing the renal morphometric measurements, and to Sue Kupcho for urinary albumin excretion measurements.

References

- 1.Brenner BM, Mackenzie HS. Nephron mass as a risk factor for progression of renal disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 1997;63:S124–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller G, Zimmer G, Mall G, Ritz E, Amann K. Nephron number in patients with primary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:101–108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner BM, Chertow GM. Congenital oligonephropathy and the etiology of adult hypertension and progressive renal injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert T, Cibert C, Moreau E, Geraud G, Merlet-Benichou C. Early defect in branching morphogenesis of the ureteric bud in induced nephron deficit. Kidney Int. 1996;50:783–795. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hostetter TH, Olson JL, Rennke HG, Venkatachalam MA, Brenner BM. Hyperfiltration in remnant nephrons: a potentially adverse response to renal ablation. American Journal of Physiology. 1981;241:F85–93. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1981.241.1.F85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wikstad I, Celsi G, Larsson L, Herin P, Aperia A. Kidney function in adults born with unilateral renal agenesis or nephrectomized in childhood. Pediatr Nephrol. 1988;2:177–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00862585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Najarian JS, Chavers BM, McHugh LE, Matas AJ. 20 years or more of follow-up of living kidney donors. Lancet. 1992;340:807–810. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saran R, Marshall SM, Madsen R, Keavey P, Tapson JS. Long-term follow-up of kidney donors: a longitudinal study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1615–1621. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.8.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldfarb DA, Matin SF, Braun WE, Schreiber MJ, Mastroianni B, Papajcik D, Rolin HA, Flechner S, Goormastic M, Novick AC. Renal outcome 25 years after donor nephrectomy. J Urol. 2001;166:2043–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossing P, Tarnow L, Nielsen FS, Hansen BV, Brenner BM, Parving HH. Low birth weight. A risk factor for development of diabetic nephropathy? Diabetes. 1995;44:1405–1407. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.12.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond K, Mauer M. The early natural history of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: II. Early renal structural changes in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:1580–1587. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mauer M, Drummond K. The early natural history of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: I. Study design and baseline characteristics of the study participants. Diabetes. 2002;51:1572–1579. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinke JM, Sinaiko AR, Kramer MS, Suissa S, Chavers BM, Mauer M, Drummond K. The early natural history of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: III. Predictors of 5-year urinary albumin excretion rate patterns in initially normoalbuminuric patients. Diabetes. 2005;54:2164–2171. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fioretto P, Steffes MW, Barbosa J, Rich SS, Miller ME, Mauer M. Is diabetic nephropathy inherited? Studies of glomerular structure in type 1 diabetic sibling pairs. Diabetes. 1999;48:865–869. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caramori ML, Kim Y, Fioretto P, Huang C, Rich SS, Miller ME, Russell GB, Mauer M. Cellular basis of diabetic nephropathy: IV. Antioxidant enzyme mRNA expression levels in skin fibroblasts of type 1 diabetic sibling pairs. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3122–3126. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fioretto P, Steffes MW, Mauer M. Glomerular structure in nonproteinuric IDDM patients with various levels of albuminuria. Diabetes. 1994;43:1358–1364. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.11.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caramori ML, Kim Y, Huang C, Fish AJ, Rich SS, Miller ME, Russell G, Mauer M. Cellular basis of diabetic nephropathy: 1. Study design and renal structural-functional relationships in patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:506–13. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maryniak RK, First MR, Weiss MA. Transplant glomerulopathy: evolution of morphologically distinct changes. Kidney Int. 1985;27:799–806. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habib R, Zurowska A, Hinglais N, Gubler MC, Antignac C, Niaudet P, Broyer M, Gagnadoux MF. A specific glomerular lesion of the graft: allograft glomerulopathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1993;42:S104–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solez K, Axelsen RA, Benediktsson H, Burdick JF, Cohen AH, Colvin RB, Croker BP, Droz D, Dunnill MS, Halloran PF, et al. International standardization of criteria for the histologic diagnosis of renal allograft rejection: the Banff working classification of kidney transplant pathology. Kidney Int. 1993;44:411–422. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, Bonsib SM, Castro MC, Cavallo T, Croker BP, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Fogo AB, Furness P, Gaber LW, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Goldberg JC, Grande J, Halloran PF, Hansen HE, Hartley B, Hayry PJ, Hill CM, Hoffman EO, Hunsicker LG, Lindblad AS, Yamaguchi Y, et al. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int. 1999;55:713–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hattori M, Kim Y, Steffes MW, Mauer SM. Structural-functional relationships in type I mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis. Kidney International. 1993;43:381–386. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen EB, Gundersen HJ, Osterby R. Determination of membrane thickness distribution from orthogonal intercepts. J Microsc. 1979;115:19–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1979.tb00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauer SM, Barbosa J, Vernier RL, Kjellstrand CM, Buselmeier TJ, Simmons RL, Najarian JS, Goetz FC. Development of diabetic vascular lesions in normal kidneys transplanted into patients with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:916–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197610212951703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauer SM, Steffes MW, Connett J, Najarian JS, Sutherland DE, Barbosa J. The development of lesions in the glomerular basement membrane and mesangium after transplantation of normal kidneys to diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1983;32:948–952. doi: 10.2337/diab.32.10.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Najarian JS, Kaufman DB, Fryd DS, McHugh L, Mauer SM, Ramsay RC, Kennedy WR, Navarro X, Goetz FC, Sutherland DE. Long-term survival following kidney transplantation in 100 type I diabetic patients. Transplantation. 1989;47:106–113. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198901000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salifu MO, Nicastri AD, Markell MS, Ghali H, Sommer BG, Friedman EA. Allograft diabetic nephropathy may progress to end-stage renal disease. Pediatr Transplantation. 2004;8:351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hariharan S, Peddi VR, Savin VJ, Johnson CP, First MR, Roza AM, Adams MB. Recurrent and de novo renal diseases after renal transplantation: A report from the renal allograft disease registry. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:928–931. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9631835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hariharan S, Adams MB, Brennan DC, Davis CL, First MR, Johnson CP, Ouseph R, Peddi VR, Pelz CJ, Roza AM, Vincenti F, George V. Recurrent and de novo glomerular disease after rneal transplantation: A report from renal allograft disease registry. Transplantation. 1999;68:635–641. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199909150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mauer SM, Goetz FC, McHugh LE, Sutherland DE, Barbosa J, Najarian JS, Steffes MW. Long-term study of normal kidneys transplanted into patients with type I diabetes. Diabetes. 1989;38:516–523. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osterby R, Nyberg G, Hedman L, Karlberg I, Persson H, Svalander C. Kidney transplantation in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Early glomerulopathy. Diabetologia. 1991;34:668–674. doi: 10.1007/BF00400997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hariharan S, Johnson CP, Bresnahan BA, Taranto SE, McIntosh MJ, Stablein D. Improved graft survival after renal transplantation in the United States, 1988 to 1996. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:605–612. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossing P, Tarnow L, Nielsen FS, Boelskifte S, Brenner BM, Parving HH. Short stature and diabetic nephropathy. BMJ. 1995;310:296–297. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6975.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bendtsen TF, Nyengaard JR. The number of glomeruli in type 1 (insulin-dependent) and type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 1992;35:844–850. doi: 10.1007/BF00399930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eshoj O, Vaag A, Borch-Johnsen K, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Beck-Nielsen H. Is low birth weight a risk factor for the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes? A population-based case-control study. J Intern Med. 2002;252:524–528. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobsen P, Rossing P, Tarnow L, Hovind P, Parving HH. Birth weight--a risk factor for progression in diabetic nephropathy? J Intern Med. 2003;253:343–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbosa J, Steffes MW, Sutherland DE, Connett JE, Rao KV, Mauer SM. Effect of glycemic control on early diabetic renal lesions. A 5-year randomized controlled clinical trial of insulin-dependent diabetic kidney transplant recipients [see comments] Jama. 1994;272:600–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steffes MW, Bilous RW, Sutherland DE, Mauer SM. Cell and matrix components of the glomerular mesangium in type I diabetes. Diabetes. 1992;41:679–684. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mauer SM, Steffes MW, Azar S, Sandberg SK, Brown DM. The effects of Goldblatt hypertension on development of the glomerular lesions of diabetes mellitus in the rat. Diabetes. 1978;27:738–744. doi: 10.2337/diab.27.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berkman J, Rifkin H. Unilateral nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis (Kimmelstiel-Wilson): report of a case. Metabolism. 1973;22:715–22. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(73)90243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]