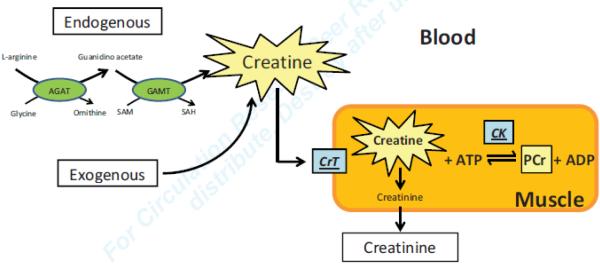

Ask any medical student for a definition of the terms “creatinine” or “creatine kinase”, and he or she will come up with a precise answer. Ask the same person for a definition of “creatine”, and the answer will be less precise. In general terms creatine is regarded as a “muscle energizer”, and in medical terms creatine is considered as the “mother substance” for both phosphocreatine and creatinine (Figure). But what is creatine? Creatine is a nitrogenous organic acid, derived from glycine, L-arginine and S-adenosyl-L-methionine which is involved in energy transfer in the form of phosphocreatine (PCr) and which is metabolized to creatinine to be excreted by the kidney. The bulk of creatine is stored in muscle, hence creatine’s name, derived from the Greek word for flesh (κϱέας). The mammalian body derives about half of its creatine stores from meat sources in food: the other half is made in the kidney and liver (Figure). The first enzyme in the pathway is L-arginine:glycine amidino transferase (AGAT). The second enzyme in the pathway of creatine synthesis is arginine-glycine aminotransferase (GATM)1. Creatine (or β-methyl guanidoacetic acid, a β-amino acid) is non-enzymatically converted to creatinine. Up until now, creatine has been considered essential for muscle energetics and function.

Figure.

The central role of creatine as substrate for the creatine kinase reaction and as substrate for the non-enzymatic conversion to creatinine. AGAT =L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (E.C.2.1.4.1) GAMT = G-Adenosyl-L-methionine:N-guanidino-methyltransferase (E.C.2.1.1.2) PCr =phosphocreatine. Not shown in the figure are the pleotropic functions of creatine, including creatine’s role in amino acid metabolism (see text).

Cardiovascular scientists have long regarded creatine as an essential metabolite in the network of energy transfer 2, 3. Indeed, the evidence for creatine and PCr as intermediaries of energy transfer is compelling and supported by a large body of literature (reviewed in 4-6). Over the years countless studies have described the multifaceted roles of PCr and the creatine kinase (CK) system. Loss of CK in heart or skeletal muscle results in contractile dysfunction. Classical experimental studies have included tissue-specific expression and subcellular location of CK isoforms, high resolution molecular structure-function relationships, and deletion of CK isoforms5. The CK/PCr system is both a buffer and a shuttle for energy-rich phosphates between the sites of ATP utilization and production, and the molecular and cellular basis for the cardioprotective action of PCr is well established7. Not surprisingly, there is also wide ranging evidence for the beneficial effects of creatine supplementation, especially in the elderly8, and in patients with muscle wasting disease9. But even more importantly, the PCr system has long been regarded essential for energy transfer in muscle.

The authors of the paper by Lygate et al. published in this issue10 are among the many who have contributed to this scenario; but they now challenge the concept of an essential role for creatine. Using a combined genetic and dietary model of creatine deficiency in mice. Lygate et al. observed no impairment in maximal exercise capacity, no changes in the response to chronic myocardial infarction, and no evidence for metabolic adaptations. In short, based on a lack of a phenotype, the workers question whether creatine is essential to support either high work load or chronic stress responses in heart and skeletal muscle10. Does this mean that creatine (and with it, the CK system) is a dispensable molecule like there are dispensable α–amino acids11? Are creatine and PCr perhaps akin to wisdom teeth in our mouth, i.e. useful but atavistic? The answer is: Probably not.

Low levels of creatine and PCr, and of CK and creatine transporter activities are all well documented features of failing hearts 2, 3, 12-16. The evidence, deduced first from measurements of creatine levels and CK activity in failing mammalian hearts and subsequently from chemical inhibitors and genetic models, seems to support a causal relation between low creatine and PCr levels and heart failure. However, doubters may raise the question whether disturbances in creatine metabolism are cause or consequence of heart failure. The new results reported by Lygate et al.10 seem to challenge the concept that low creatine concentrations in heart muscle mediate impaired contractile function of failing heart muscle (as has been proposed), or that low creatine transporter levels or low CK activity are mediators of maladaptive responses to hemodynamic and neurohumonal stresses. The data also cast doubt on the usefulness of creatine as a performance enhancing drug in athletes, or as a drug for the treatment of cachexia and the plerotropic effects of creatine, including adenine nucleotide metabolism, cardioprotection and promotion of protein synthesis5.

One question to ask is: Why has evolutionary pressure put creatine into the system of cells with high rates of energy turnover (heart, brain, skeletal muscle)? According to Brosnan et al17 creatine synthesis consumes 20 – 30% of arginine’s amidino groups, regardless of whether provided in the diet or synthesized by the body. Creatine synthesis is indeed a major pathway in amino acid metabolism, especially metabolism of arginine and methionine. So there is an undisputed role for creatine in amino acid and nitrogen metabolism. There is also a role for creatine in protection of the ischemic, reperfused myocardium as the authors of the present study have recently shown 18.

Are we looking for the key under the lamp post? A number of issues come to mind. First, the creatine/PCr system is only one part of the complex and highly regulated system of enzyme catalyzed reactions involved in energy transfer in living tissues19. Just like the stock market reflects the economy, it is not the economy itself. Secondly, only very few of us have considered the problem of how signal transduction events in heart (or any other tissue) are connected to cellular metabolism 20. We probably still do not know enough and all the hard work of the brightest investigators is still not immune from the “IKEA Effect” (a term used by economists to denote the increase in valuation of one’s own work)21. Third, and in spite of what has just been said, CK-catalyzed phosphotransfer is undoubtedly a major component of the energy-rich phosphate transfer coupling ATP production in mitochondria to sites of ATP hydrolysis22.

The big enigma is: Why is the loss of substrate for the CK reaction tolerated by the mouse hearts, while loss of the enzyme CK is not? Both should be physiologically equivalent. The central issue here is whether the adaptive responses to the loss of CK may also exist hearts with no creatine. Deletion of CK induces a shift in substrate utilization networks by redirecting phosphotransfer flux through alternative adenylate kinase23, glycolytic and guanine nucleotide systems22, 24. The present study may not have captured these adaptations. First, the authors have focused on the proteome of Cr-deficient mouse hearts at baseline, and did not assess whether there are differences in the proteome during heart failure. Given that there were little or no changes in the activities of possible compensatory phosphotransfer enzymes in CK-deficient mouse hearts, it is not surprising to see no changes in the proteome of normal creatine-deficient mouse hearts. Secondly, some critical measurements yet to be made are flux through other phosphotransfer pathways and the assessment of changes in the metabolomic profile. Third, as pointed out by the authors, no information is available on any differences in post-translational modifications. Fourth, although the comprehensive in vivo characterization of the creatine-deficient model includes increased hemodynamic loads in response to exercise and myocardial infarction, an acute increase in work load is probably the best way to expose the function of PCr as an intracellular buffer for ATP 25. This was not attempted. Lastly, echoing the recent article suggesting that mice may not be a good model for human diseases26, the mismatch in genotype-phenotype for the CK system in the mouse compared to large mammals including man suggests that the mouse may be an interesting anomaly. In short, the reasons why Cr-deficient mouse hearts do not demonstrate the phenotype observed for CK-deficient mouse hearts by many investigators, including these authors, remain undefined.

The study by Lygate et al 10 thus exposes a new facet of the complexity of energy transfer in the heart. It is not the end, but only the beginning of further investigations into the burning question whether “energy starvation” of the failing heart 4 is cause or consequence of contractile dysfunction. The metabolic derangements in the failing heart are now being assessed by a wide array of tools ranging from metabolomic to proteomic and transcriptionic analyses. They are probably as complex as the system of energy transfer itself27. The paper by Lygate et al.10 heightens our awareness that the study of metabolic regulation in heart and skeletal muscle still yields some big surprises.

Acknowledgements

We thank Roxy A. Tate for expert editorial assistance, and Truong Lam, for the illustration.

Sources of Funding We are grateful for funding support by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: 5R01HL073162 and 5R01HL061483 (HT).

Footnotes

Disclosures None

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Walker JB. Creatine: Biosynthesis, regulation, and function. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1979;50:177–242. doi: 10.1002/9780470122952.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingwall JS, Kramer MF, Fifer MA, Lorell BH, Shemin R, Grossman W, Allen PD. The creatine kinase system in normal and diseased human myocardium. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1050–1054. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510243131704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neubauer S, Remkes H, Spindler M, Horn M, Wiesmann F, Prestle J, Walzel B, Ertl G, Hasenfuss G, Wallimann T. Downregulation of the Na(+)-creatine cotransporter in failing human myocardium and in experimental heart failure. Circulation. 1999;100:1847–1850. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.18.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingwall JS, Weiss RG. Is the failing heart energy starved? On using chemical energy to support cardiac function. Circ Res. 2004;95:135–145. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137170.41939.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallimann T, Tokarska-Schlattner M, Schlattner U. The creatine kinase system and pleiotropic effects of creatine. Amino Acids. 2011;40:1271–1296. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0877-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyss M, Kaddurah-Daouk R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1107–1213. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saks V, Stepanov V, Jaliashvili IV, Konorev EA, Kryzkanovsky SA, Strumia E. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of action for the cardioprotective and therapeutic role of creatine phosphate. In: Conway MA, Clark JF, editors. Creatine and creatine phosphate: Scientific and clinical perspectives. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Candow DG. Sarcopenia: Current theories and the potential beneficial effect of creatine application strategies. Biogerontology. 2011;12:273–281. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME. Creatine: Endogenous metabolite, dietary, and therapeutic supplement. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:241–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lygate CA, Aksentijevic D, Dawson D, Ten Hove M, Phillips D, de Bono JP, Medway DJ, Sebag-Montefiore LM, Hunyor I, Channon K, Clarke K, Zervou S, Watkins H, Balaban R, Neubauer S. Living without creatine: Unchanged exercise capacity and response to chronic myocardial infarction in creatine-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2013;112:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300725. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeds PJ. Dispensable and indispensable amino acids for humans. J Nutr. 2000;130:1835S–1840S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.7.1835S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingwall JS, Atkinson DE, Clarke K, Fetters JK. Energetic correlates of cardiac failure: Changes in the creatine kinase system in the failing myocardium. Eur Heart J. 1990;11(Suppl B):108–115. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/11.suppl_b.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway MA, Allis J, Ouwerkerk R, Niioka T, Rajagopalan B, Radda GK. Detection of low phosphocreatine to atp ratio in failing hypertrophied human myocardium by 31p magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Lancet. 1991;338:973–976. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91838-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nascimben L, Ingwall JS, Pauletto P, Friedrich J, Gwathmey JK, Saks V, Pessina AC, Allen PD. Creatine kinase system in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circulation. 1996;94:1894–1901. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.8.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saupe KW, Spindler M, Tian R, Ingwall JS. Impaired cardiac energetics in mice lacking muscle-specific isoenzymes of creatine kinase. Circ Res. 1998;82:898–907. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.8.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lygate CA, Schneider JE, Neubauer S. Investigating cardiac energetics in heart failure. Exper Physiol. 2012 Sept. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.064709. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brosnan JT, da Silva RP, Brosnan ME. The metabolic burden of creatine synthesis. Amino Acids. 2011;40:1325–1331. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0853-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lygate CA, Bohl S, ten Hove M, Faller KM, Ostrowski PJ, Zervou S, Medway DJ, Aksentijevic D, Sebag-Montefiore L, Wallis J, Clarke K, Watkins H, Schneider JE, Neubauer S. Moderate elevation of intracellular creatine by targeting the creatine transporter protects mice from acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96:466–475. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlstaedt A, Fliegner D, Kararigas G, Ruderisch HS, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Holzhutter HG. Cardionet: A human metabolic network suited for the study of cardiomyocyte metabolism. BMC Sys Biol. 2012;6:114. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson CB. Rethinking the regulation of cellular metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:23–29. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2012.76.010496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norton MI, Mochon D, Ariely D. The “IKEA Effect”: When labor leads to love. J Consumer Psychol. 2012;22:453–460. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingwall JS. Phosphotransfer reactions in the failing heart. In: Patterson C, Willis MS, editors. Translational cardiology. Molecular basis of cardiac metabolism, cardiac remodeling, translational therapies and imaging techniques. Humana Press; New York: 2012. pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dzeja PP, Hoyer K, Tian R, Zhang S, Nemutlu E, Spindler M, Ingwall JS. Rearrangement of energetic and substrate utilization networks compensate for chronic myocardial creatine kinase deficiency. J Physiol. 2011;589:5193–5211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.212829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V, Joubert F. Bioenergetics of the failing heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1360–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin GW, Taylor CS, Taegtmeyer H. Regulation of energy metabolism of the heart during acute increase in heart work. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29530–29539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seok J, Warren HS, Cuenca AG, Mindrinos MN, Baker HV, Xu W, Richards DR, McDonald-Smith GP, Gao H, Hennessy L, Finnerty CC, Lopez CM, Honari S, Moore EE, Minei JP, Cuschieri J, Bankey PE, Johnson JL, Sperry J, Nathens AB, Billiar TR, West MA, Jeschke MG, Klein MB, Gamelli RL, Gibran NS, Brownstein BH, Miller-Graziano C, Calvano SE, Mason PH, Cobb JP, Rahme LG, Lowry SF, Maier RV, Moldawer LL, Herndon DN, Davis RW, Xiao W, Tompkins RG. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Feb. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222878110. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taegtmeyer H. Energy metabolism of the heart: From basic concepts to clinical applications. Curr Prob Cardiol. 1994;19:57–116. doi: 10.1016/0146-2806(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]