Abstract

Flavivirus replication is accompanied by the rearrangement of cellular membranes that may facilitate viral genome replication and protect viral components from host cell responses. The topological organization of viral replication sites and the fate of replicated viral RNA are not fully understood. We exploited electron microscopy to map the organization of tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) replication compartments in infected cells and in cells transfected with a replicon. Under both conditions, 80-nm vesicles were seen within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that in infected cells also contained virions. By electron tomography, the vesicles appeared as invaginations of the ER membrane, displaying a pore that could enable release of newly synthesized viral RNA into the cytoplasm. To track the fate of TBEV RNA, we took advantage of our recently developed method of viral RNA fluorescent tagging for live-cell imaging combined with bleaching techniques. TBEV RNA was found outside virus-induced vesicles either associated to ER membranes or free to move within a defined area of juxtaposed ER cisternae. From our results, we propose a biologically relevant model of the possible topological organization of flavivirus replication compartments composed of replication vesicles and a confined extravesicular space where replicated viral RNA is retained. Hence, TBEV modifies the ER membrane architecture to provide a protected environment for viral replication and for the maintenance of newly replicated RNA available for subsequent steps of the virus life cycle.

INTRODUCTION

Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) is the etiological agent of tick-borne encephalitis, a potentially fatal infection of the central nervous system occurring throughout wide areas in Europe and Asia (1–3). TBEV is the most medically important member of the mammalian tick-borne group of the genus Flavivirus within the family Flaviviridae (4). Flaviviruses are a large group of arboviruses that are responsible for severe diseases in humans and animals. This virus group includes, in addition to TBEV, the dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus (YFV), West Nile virus (WNV), and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV). They have in common an enveloped virus particle that contains a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome, a similar genomic organization, and comparable replication strategies (5, 6). After entry, the incoming viral RNA is translated, giving rise to a polyprotein precursor that is processed by cellular proteases and the viral protease NS2B/3 to obtain three structural and seven nonstructural proteins (NS). The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) residing in NS5 synthesizes complementary negative-strand RNA from genomic RNA, with negative strands serving as the template for the synthesis of new positive-strand viral RNAs.

Like all positive-strand RNA viruses, flaviviruses replicate in the cytoplasm in close association with virus-induced intracellular membrane structures. It is generally accepted that the formation of these replication compartments (RC) provide an optimal microenvironment for viral RNA replication by limiting diffusion of viral/host proteins and viral RNA, thereby increasing the concentration of components required for RNA synthesis, and by providing a scaffold for anchoring the replication complex (7). In addition, these virus-induced membranes may also shield double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) replication intermediates from host cell-intrinsic surveillance (8–10). Elegant electron tomography (ET) studies on DENV- and WNV-infected cells have recently provided the first three-dimensional (3D) view of the architecture of flavivirus RCs (11, 12). In these studies, different virus-induced membrane structures appeared to be part of a highly organized network of ER-derived rearranged membranes. Vesicle packets, containing dsRNA and proteins of the replication complex, have been described as the sites of virus replication and appear in ET as invaginations of the ER membrane bearing pore-like connections to the cytoplasm and possibly between themselves. Convoluted membranes (CM) that are specifically enriched in NS2B/3 have been proposed as the putative sites of protein synthesis and proteolytic cleavage (11, 13–15).

However, although ET images from fixed cells can provide a high-resolution snapshot of the complex network of vesicles and interconnections, they cannot address the dynamic exchange of proteins and viral RNA throughout these compartments. In order to provide a global picture of the spatiotemporal organization of the RCs, it is therefore important to integrate high-resolution imaging approaches with innovative techniques that allow exploring in real time the dynamic interplay between viruses and their hosts. Engineered subgenomic replicons expressing fluorescently tagged nonstructural proteins (16–18) have been exploited to investigate the distribution and dynamics of HCV replicase proteins. However, the only available tool to explore flaviviral RNA trafficking has been reported for TBEV (19). The method is based on TBEV replicons containing multiple high-affinity binding sites for the phage MS2 core protein fused to an autofluorescent protein. Replicated viral RNA could then be visualized in living cells, thus providing the first description of flavivirus RNA dynamics in living cells (19).

In this work, we took advantage of immunoelectron microscopy (immuno-EM), thin-section transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and high-resolution ET in combination with live-imaging approaches for TBEV RNA to identify replication compartments in infected and replicon-transfected cells. We precisely mapped the spatial organization of virus-induced membranes and vesicles and studied the mobility of replicated viral RNA. We propose a model where replication vesicles and the extravesicular space form an optimized environment to support efficient virus replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and plasmids.

Baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) and African green monkey (Vero E6) cell lines were grown under standard conditions in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. BHK21-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)-MS2nls cells are a cell pool stably expressing EYFP-MS2nls and blasticidin S-deaminase, and they were cultured in the presence of 10 μg/ml blasticidin. Lentiviral particles for the transduction of the EYFP-MS2nls gene were prepared in 293T cells exactly as described previously (20) using pWPI-BLR-EYFP-MS2nls and packaging constructs pCMVR8.91 and pMD.G (provided by Didier Trono). Working stocks of TBEV strain Neudoerfl were propagated and titrated on Vero E6 cells. pWPI-BLR-EYFP-MS2nls was used to generate a cell line constitutively expressing the EYFP-MS2nls protein suitable for immuno-EM studies. The EYFP-MS2nls gene was isolated from pEYFP-MS2nls (21) by XbaI digestion and then inserted into the multiple cloning site (MCS) of the pWPI-BLR vector (provided by Volker Lohmann) via the SpeI restriction site. The construct pTNd/ΔME_24×MS2, the replication-deficient TNd/ΔME_24×MS2_GAA replicon carrying the GDD-to-GAA mutation in the viral NS5 protein, and the pMS2-EYFP, pEYFP-MS2nls, and pCherry-MS2nls vectors used for visualization purposes were previously described (19, 21).

RNA transcription and transfection.

Subgenomic replicon RNAs were transcribed in vitro as described in detail elsewhere (19, 22). A total of 4 × 106 cells were resuspended in 400 μl ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and mixed in a 0.4-cm gene-pulser cuvette with 10 μg of RNA to be electroporated with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser apparatus at 0.25 kV with a capacitance of 960 μF (19). After electroporation, cells were washed in complete growth medium without antibiotics and seeded in the same medium.

Sample staining and imaging for indirect immunofluorescence analysis.

Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis was performed 24 h upon infection or transfection. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min, incubated for 5 min with 100 mM glycine, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Subsequently, the cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min with PBS, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.1% Tween 20 before incubation with antibodies. The coverslips were rinsed three times with PBS-0.1% Tween 20 (washing solution) and incubated for 1 h with secondary antibodies. Donkey antibodies specific for rabbit or mouse immunoglobulin G and conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) were used for this analysis. Coverslips were finally washed three times with washing solution and mounted on slides using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). For the detection of viral antigens, we used the following antibodies: mouse monoclonal antibody detecting NS1 (provided by Connie Schmaljohn), polyclonal rabbit anti-TBEV serum that can be used for both structural and nonstructural protein detection (23) (provided by Franz X. Heinz), and polyclonal rabbit anti-prM serum (provided by Franz X. Heinz). The J2 mouse monoclonal anti-dsRNA antibody (English and Scientific Consulting, Szirak, Hungary) was used to detect replication complexes, whereas for the ER staining we used the mouse monoclonal anti- protein disulfide isomerase (PDI; AB2792; Abcam) antibody. Fluorescent images of fixed cells were captured on a Zeiss LSM510 META confocal microscope with a 63× Plan-Apochromat oil objective having a 1.4 numerical aperture (NA). The pinhole of the microscope was adjusted to get an optical slice of less than 1.0 μm for any wavelength acquired.

Epoxy embedding of cells for transmission electron microscopy.

BHK-21 cells grown on 10-cm-diameter dishes were infected with TBEV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 or transfected with in vitro transcribed TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 replicon RNA. After 24 h, cells were washed 3 times with prewarmed PBS and fixed for 30 min with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (GA) in 50 mM Na-cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 M KCl, 0.1 M MgCl2, 0.1 M CaCl2, and 2% sucrose. Cells were washed 5 times for 5 min each with 50 mM Na-cacodylate buffer and postfixed on ice in the dark with 2% OsO4 in 50 mM Na-cacodylate buffer for 40 min. After the cells were washed overnight in distilled water, they were treated with 0.5% uranylacetate (UA; dissolved in water) for 30 min, rinsed thoroughly with water, and dehydrated in a graded ethanol series at room temperature (40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, and 80%, 5 min each; then 95% and 100%, 20 min each). Cells were immersed in 100% propylene oxide and immediately embedded in an Araldite-Epon mixture (Araldite 502/Embed 812 kit; Electron Microscopy Sciences). After polymerization at 60°C for 2 days, embedded cells were sectioned using a Leica Ultracut UCT ultramicrotome and a 35° diamond knife (Diatome, Biel, Switzerland). Sections with a thickness of 60 nm were collected onto 100-mesh copper grids that had been coated with Formvar (Plano, Wetzlar, Germany) and coated with carbon. Sections were counterstained with 2% lead citrate in H2O for 2 min. Samples were analyzed by using a Biotwin CM120 Philips electron microscope (100 kV) equipped with a bottom-mounted 1K charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera (Keen View; SIS, Münster, Germany).

Immunolabeling of thawed cryosections.

TBEV-infected and replicon-transfected cells were fixed by adding an equal amount of 8% PFA and 0.2% GA in 0.2 M PHEM buffer (120 mM Pipes, 100 mM HEPES, 4 mM MgCl2, 40 mM EGTA, pH 6.9) to the culture medium for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then fixed for 1 h with 4% PFA and 0.1% GA in 0.1 M PHEM at room temperature. The fixative was removed and the cells were stored at 4°C in 4% PFA in 0.1 M PHEM until further processing. After extensive washing with 0.1 M PHEM, remaining aldehyde groups were blocked with 30 mM glycine in 0.1 M PHEM. Cells were scraped off the plate, embedded in 10% gelatin, and infiltrated in 2.3 M sucrose overnight at 4°C. Cell pellets were mounted onto sample holder pins, frozen, and stored in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections (60 nm) were prepared using a Leica Ultracut UC6 microtome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and a diamond knife (Diatome, Biel, Switzerland). Sections were picked up with a mixture of 2% methylcellulose and 2.3 M sucrose (1:1) and, after being thawed, were transferred to 100-mesh Formvar- and carbon-coated grids. Labeling of thawed cryosections was performed essentially as described elsewhere (24). In brief, sections were molten by floating on 2% gelatin for 30 min at 37°C and incubated in 30 mM glycine in PBS for 10 min and then at 30 min at room temperature in blocking solution (PBG; 0.8% [wt/vol] BSA [Sigma], 0.1% [wt/vol] fish skin gelatin [Sigma] in PBS). Sections were then incubated with primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer, for 30 min at room temperature. After being washed 5 times, for 5 min each time, in blocking buffer, sections were incubated with rabbit anti-mouse antibody followed by protein A coupled to 10-nm gold particles (Cell Microscopy Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands) diluted in blocking solution. After being washed with PBS and distilled water, grids were contrasted with a mix of 2% methylcellulose and 3% UA (1:6) for 10 min on ice.

Electron tomography.

Sections of 250-nm thickness were collected on palladium-copper slot grids (Science Services, Munich, Germany) coated with Formvar (Plano, Wetzlar, Germany). Protein A-gold (10 nm) was added to both sides of the sections as fiducial markers. Single- and dual-axis tilt series were acquired with an FEI Tecnai TF30 microscope operated at 300 kV and equipped with a 4k FEI Eagle camera (binning factor 2, on the specimen level) over a −65° to 65° tilt range (increment of 1°) and at an average defocus of −0.2 μm. Tomograms were reconstructed using the weighted back projection method implemented in the IMOD software package (version 3.11.5) (25). Rendering of the three-dimensional surface of the tomograms was performed by using the AMIRA visualization software package (version 5.4.2; Visage Imaging, Berlin, Germany). Models were generated from unfiltered and 2× binned tomograms by manually masking areas of interest, thresholding, and smoothing labels.

Microscopy and live imaging acquisition.

BHK-21 cells were electroporated with the TBEV replicons' RNA and plated on glass-bottom plates (MatTek, Ashland, MA). For the visualization of the viral RNA, cells were cotransfected either with MS2-EYFPnls, expressing a hybrid protein composed by the core protein of the MS2 bacteriophage fused to EYFP and to a nuclear localization signal (NLS), or with the same construct without the NLS. At the appropriate time point posttransfection, cells were transferred on a humidified and CO2-controlled on-stage incubator (PeCon GmbH, Erbach, Germany) at 37°C in complete DMEM without phenol red for live cell imaging. For fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments, images of 512 by 512 pixels (29.25 by 29.25 μm) and optical thickness of 1 μm were acquired using 1% or less of the power of the 514-nm laser line. EYFP was bleached at 514 nm (Argon laser; maximum output of 500 of milliwatts) in a circle of 30 pixels of diameter, at full laser power, for 10 passages. For fluorescence loss in photobleaching (FLIP) measurements, images were acquired as described above, and bleaching was performed at every acquisition. Images were analyzed with ImageJ (W. S. Rasband, ImageJ; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

RESULTS

Subcellular localization of TBEV proteins and dsRNA in infected cells.

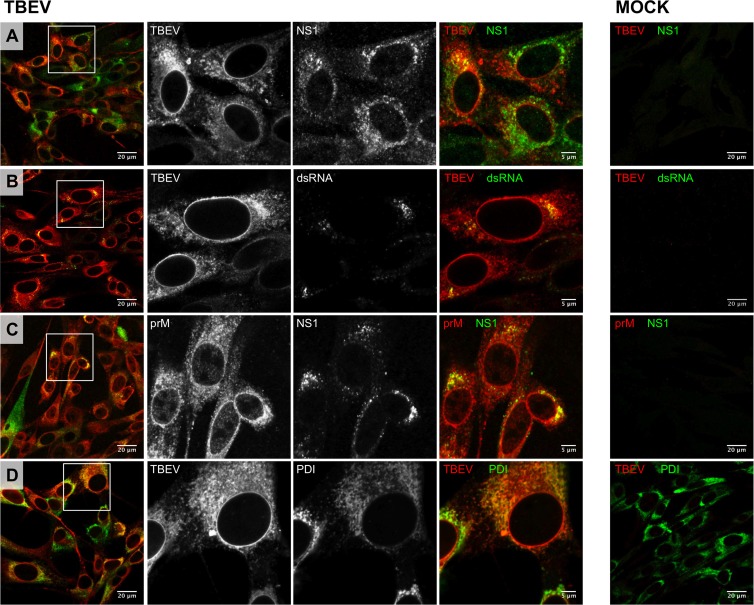

As a first step to study the organization of TBEV replication sites, we characterized by immunofluorescence the subcellular localization of proteins and dsRNA in virus-infected BHK-21 cells. At 24 h postinfection (hpi), viral proteins detected with a polyclonal TBEV-specific antiserum (predominantly recognizing the structural protein E and NS1) were localized in the perinuclear region and in discrete and irregularly shaped foci (Fig. 1A). As expected, these structures partially colocalized with NS1-containing cytoplasmic foci (Fig. 1A) as well as with the dsRNA replication intermediate (Fig. 1B), a well-accepted marker for flaviviral replication vesicles (11, 12, 15, 26). A similar distribution pattern was observed with the prM-specific antibody that also showed partial colocalization with NS1 cytoplasmic foci (Fig. 1C). In addition, coimmunolocalization studies of viral proteins and the rER marker protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) suggested that ER-derived membranes provide the framework for the membranous TBEV replication compartments (Fig. 1D). These data are in agreement with our previous observations for the MS2-tagged TBEV replicon where newly synthesized viral RNA associates with viral proteins and dsRNA replication intermediates in rER-derived cytoplasmic compartments (8, 19).

Fig 1.

Localization of TBEV proteins and dsRNA in BHK-21-infected cells. BHK-21 cells were either mock infected (MOCK; right) or infected with TBEV at an MOI of 2 (TBEV; left). After 24 h, cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Cells costained with the anti-TBEV antiserum (TBEV; Alexa Fluor 594, red) and with the monoclonal anti-NS1 antibody (NS1; Alexa Fluor 488, green); (B) cells costained with the anti-TBEV antiserum (TBEV; Alexa Fluor 594, red) and with the J2 monoclonal anti-dsRNA antibody (dsRNA; Alexa Fluor 488, green); (C) cells costained with the anti-prM antiserum (prM; Alexa Fluor 594, red) and with the monoclonal anti-NS1 antibody (NS1; Alexa Fluor 488, green); (D) cells costained with the anti-TBEV antiserum (TBEV; Alexa Fluor 594, red) and with the anti-PDI monoclonal antibody (PDI; Alexa Fluor 488, green). The zoomed images shown in the middle panels correspond to boxed regions in the left panels.

Electron tomography analysis of TBEV-induced membrane alterations.

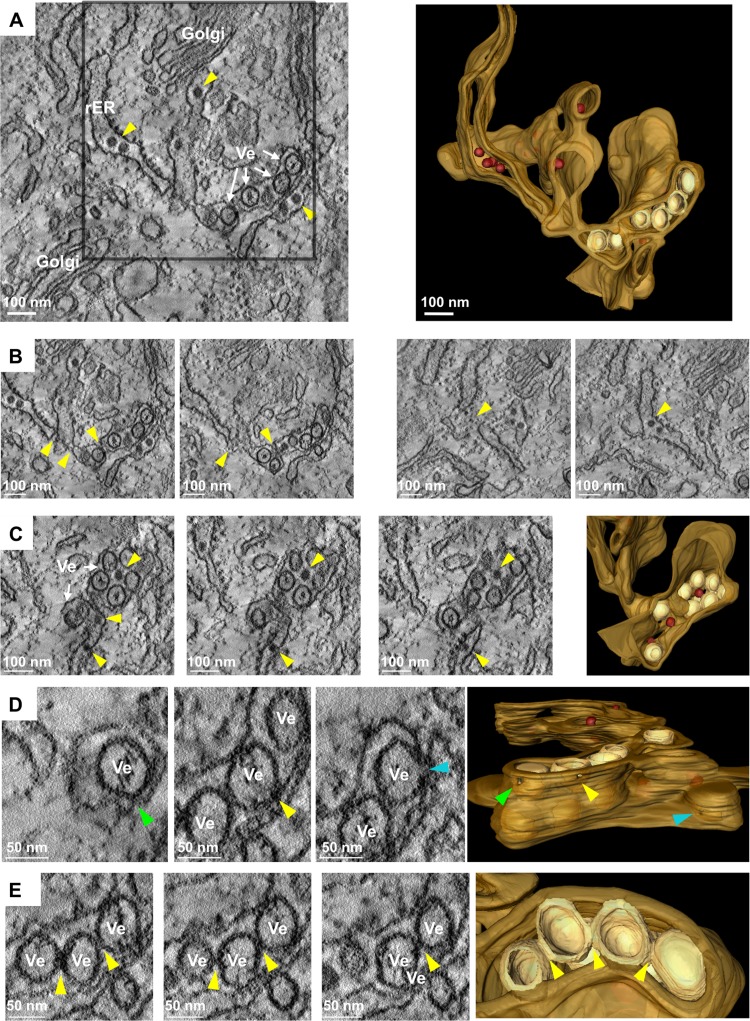

To reveal the three-dimensional organization of virus-induced membrane alterations, we performed a detailed ET analysis of TBEV-infected cells. At 24 hpi, BHK-21 cells were fixed, resin embedded, and sectioned as described in Materials and Methods. Tomograms from 250-nm-thick sections were acquired and reconstructed. As shown in Fig. 2, TBEV infection induced membrane alterations reminiscent of those previously described for mosquito-borne flaviviruses like DENV and WNV (11, 12, 27) and more recently also for Langat virus (LGTV), a naturally attenuated tick-borne flavivirus (28). Virus-induced single-membrane vesicles (Ve) with a diameter of 80 nm (±10.6 nm; n = 70) were observed in the lumen of a dilated rER and appeared to be part of an elaborate reticulovesicular network of interconnected membranes (Fig. 2A and B). ER-derived cisternae filled with viral particles in the proximity of virus-induced vesicles, as well as individual virions trafficking throughout the secretory pathway, could also be detected (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, during our studies, we frequently noticed virus particles with a diameter of about 40 nm (Fig. 2A and C, yellow arrowheads) and TBEV-induced vesicles sharing the same ER lumen (Fig. 2B; see also Movie S1 in the supplemental material). This finding supports the notion that replication, occurring in vesicles, and assembly of new virions takes place in very close proximity (11).

Fig 2.

Ultrastructural analysis of the membrane alterations induced by TBEV infection. (A) BHK-21 cells were infected with TBEV at an MOI of 2, fixed 24 hpi, and processed for ET as described in Materials and Methods. Left, tomographic slice of a dual-axis tomogram, shown in Movie S2 in the supplemental material. Upon infection, vesicles (Ve) and virions (yellow arrowheads) were observed in the lumen of the rough ER. Right, 3D surface reconstruction of the whole tomogram displaying the TBEV-induced vesicles (in light yellow) in the lumen of the ER (in light brown), as well as virions (in dark red). (B) Two examples (left and right) of tomographic slices through the whole tomogram depicting connections between ER tubules (yellow arrows). (C) Left, tomographic slices of the same dual-axis tomogram depicting several of these vesicles in the lumen of the ER in close proximity to newly assembled virions (yellow arrows), also observed in the Golgi apparatus (see Movie S1); right, 3D surface rendering of the same area displaying the TBEV-associated vesicles (in light yellow) sharing the ER lumen with TBE virions (in dark red) and surrounded by ER membranes (in light brown). (D) Left, serial single slices depicting openings of several TBEV-induced vesicles to the cytosol (green, yellow, and blue arrows); right, XZ view of the 3D reconstruction of the whole tomogram displaying these openings toward the cytosol (arrows with matching colors). (E) Left, slices through the tomogram showing tight contacts of TBEV-induced vesicles with their neighboring vesicles (yellow arrows); right, 3D reconstruction displaying these contacts between vesicles. Note that openings connecting vesicles were not observed in these tomograms.

In agreement with earlier reports (11, 12, 28, 29), detailed tomographic analysis revealed pore-like structures (Fig. 2C; yellow arrowheads) connecting the lumen of the vesicles to the cytosol. These pore-like openings could be detected in approximately 50% of the vesicles included in these tomograms (n = 14) (Fig. 2D). In addition, we found that adjacent/neighboring vesicles were frequently tightly packed, but pore-like openings between them were not observed (Fig. 2E). This observation differs from what has been previously reported for WNV (12) or LGTV (28). Whether this depends on the virus or the cell type or the sample preparation method remains to be established.

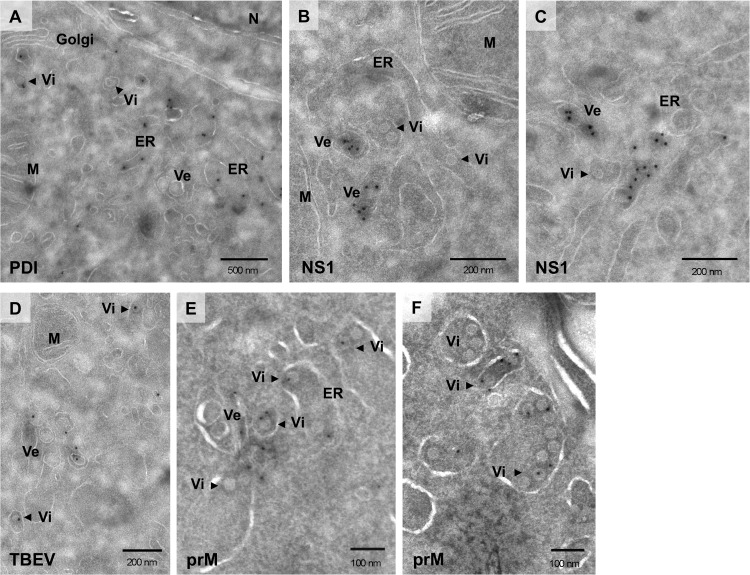

Association of viral proteins with ER-derived membrane alterations induced in infected cells.

To further characterize the ultrastructural modifications induced by TBEV infection and to allocate viral proteins to specific membrane alterations, we performed immuno-EM experiments on TBEV-infected BHK-21 cells. Thawed cryosections labeled with antibodies against the ER marker PDI clearly showed that virus-induced vesicles as well as newly assembled immature virions (Vi; arrowheads) localize in the lumen of a dilated and rearranged ER compartment (Fig. 3A), thus supporting our earlier immunofluorescence microscopy studies (Fig. 1D) (19). A monoclonal antibody to the NS1 protein (30) was used to mark TBEV-induced replication vesicles. As shown in Fig. 3B and C, gold particles predominantly labeled 80-nm virus-induced vesicles that were frequently located in the proximity of ER cisternae containing progeny virions (arrowheads). However, NS1 could also be detected in the lumen of the ER or within the Golgi compartment, consistent with its putative roles in different steps of the viral life cycle (data not shown). TBEV-induced vesicles were also efficiently labeled with the rabbit polyclonal anti-TBEV serum we previously used for immunofluorescence analysis of infected BHK-21 cells, which recognizes both NS1 and the structural protein E (Fig. 3D). Attempts to label replication sites in immuno-EM with the J2 antibody against dsRNA or with other antibodies raised against NS3 or NS5 were unsuccessful. Viral particles trafficking toward the Golgi compartment were also labeled with the polyclonal anti-TBEV serum (Vi; arrowheads). In addition, antibodies against the structural protein prM showed specific labeling of TBEV particles (Fig. 3E and F). These particles were either located in the lumen of the ER, frequently adjacent to virus-induced vesicles, or accumulated within dilated ER cisternae, arguing that they represent newly assembled progeny virions.

Fig 3.

Immunogold EM of TBEV-infected cells. BHK-21 cells were infected with TBEV at an MOI of 2 and fixed 24 hpi, and thawed cryosections were labeled with antibodies against PDI (A), NS1 (B and C), and prM (E and F) and with the anti-TBEV serum (D) that predominantly recognizes the structural protein E and the nonstructural protein NS1. Vesicles within the lumen of dilated ER cisternae (A) are specifically labeled with anti-NS1 (B and C) and anti-TBEV antibodies (D). Arrowheads in all panels highlight TBEV virions, specifically labeled with prM (E and F) and TBEV (D) antibodies, in the lumen of the ER or trafficking toward the Golgi apparatus. Abbreviations: M, mitochondria; N, nucleus; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Ve, vesicles; Vi, virions.

Ultrastructural analysis of replicon-transfected BHK-21 cells.

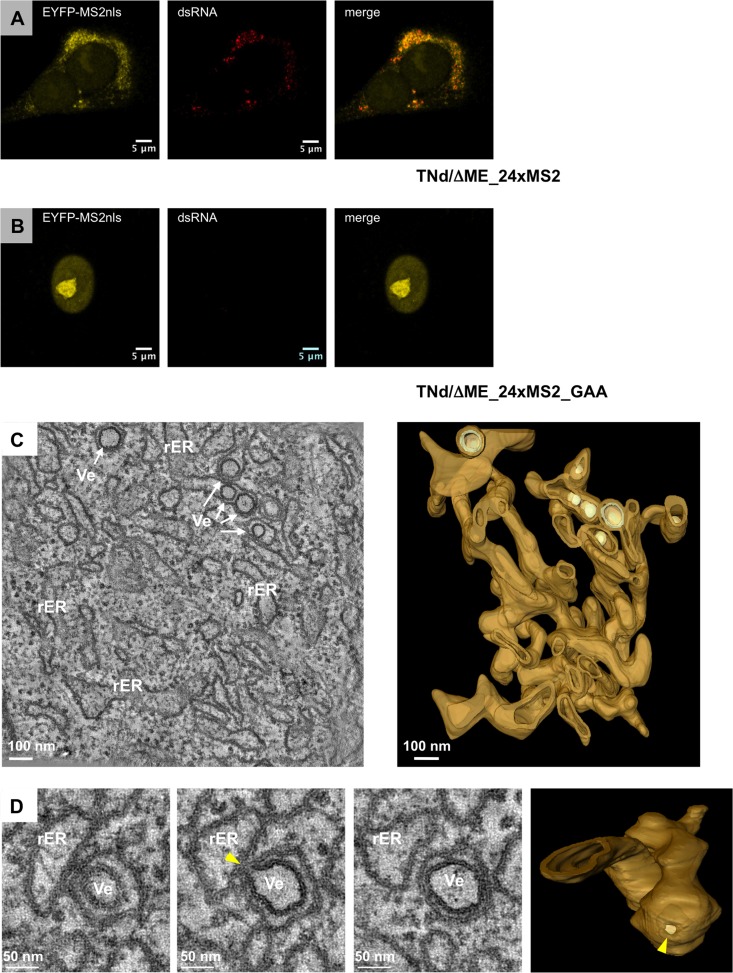

The ultimate goal of this study was to address TBEV RNA trafficking within virus-induced intracellular compartments by exploiting the MS2-based replicon system we previously established (19). In order to ascertain that transfection of MS2-tagged TBEV-derived subgenomic replicons induces the same characteristic membrane alterations observed upon virus infection, we conducted the analogous analysis as described above and compared the morphology of membranous structures by using semithick sections (250 nm) prepared from replicon-transfected or virus-infected cells. For this set of experiments, we used BHK21-EYFP-MS2nls cells transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing the nuclear variant of the EYFP-MS2 fusion protein. Previously, in order to tag TBEV replicons, we always used a form of EYFP-tagged MS2 that localized both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm (8, 19, 31). However, we noticed that the accumulation of tagged TBEV RNA in the cytoplasm corresponded to a depletion of the MS2 nuclear stain. Therefore, in order to increase the signal-to-noise ratio in the cytoplasm, we exploited an EYFP-MS2 protein with a nuclear localization signal (NLS) for exclusive nuclear localization in the absence of TBEV replication. EYFP-MS2nls remains associated with the replicated TBEV RNA carrying the MS2 binding sites in the cytoplasm against a dark background, offering a better tool for both dynamic and ultrastructural studies. As shown in Fig. 4A, extensive colocalization of EYFP-MS2nls with dsRNA was observed in the ER-derived perinuclear compartment in cells transfected with the TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 wild-type replicon, whereas control cells transfected with the replicon carrying an inactive NS5 RdRp showed only nuclear localization of EYFP-MS2nls (Fig. 4B). Detailed tomographic analysis of cells fixed 24 h after transfection revealed rather small rER cisternae in comparison to infected cells. These smaller ER tubules form a network of fragmented ER in the perinuclear region of transfected cells (Fig. 4C; see also Movies S3 and S4 in the supplemental material). Nevertheless, vesicles were observed in the rER lumen, having an average diameter of 85 nm (±19.6 nm; n = 70). In addition, similar to what we found in infected cells, most of the vesicles (75%; n = 35) detected in replicon-transfected cells had a pore-like opening toward the cytosol (Fig. 4D). Based on the similarity between replicon- and infection-induced membranous structures and by analogy to dengue virus (11), we concluded that TBEV-induced vesicles play a role in virus replication.

Fig 4.

Ultrastructural analysis of the membrane alterations induced by pTNd/ΔME_24×MS2. (A) BHK21-EYFP-MS2nls cells were electroporated with the TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 replicon RNA. Twenty-four hours postelectroporation (hpe), cells were fixed, permeabilized with Triton X-100, and incubated with an antibody against dsRNA that was then revealed by a secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa-594. The EYFP channel is shown in the left panel, dsRNA in the middle panel, and the merge in the right panel. (B) BHK21-EYFP-MS2nls cells were electroporated with the TNd/ΔME_24xMS2_GAA replicon RNA and treated as described for panel A. (C) BHK21-EYFP-MS2nls cells were electroporated with TNd/ΔME_24×MS2, fixed 24 hpe, and processed for ET as described in Materials and Methods. Left, slice of a dual-axis tomogram showing the TBEV-induced vesicles (Ve) in the ER lumen; right, 3D reconstruction of the complete tomogram. ER membranes are depicted in light brown and TBEV-induced vesicles in light yellow. This tomogram and its 3D membrane rendering are shown in Movie S4 in the supplemental material. (D) Left, serial single slices through the same tomogram displaying connections between adjacent ER tubules; right, 3D reconstruction of the whole tomogram showing a network of interconnected ER tubules. Note that the ER is highly fragmented in these cells in comparison to infected cells. (E) Left, serial single slices through the same tomogram displaying an opening toward the cytosol of a TBEV-induced vesicle (yellow arrows); right, 3D surface model showing this opening that connects the interior of the vesicle with the cytosol.

Immuno-EM analysis of replicon-transfected BHK-21 cells.

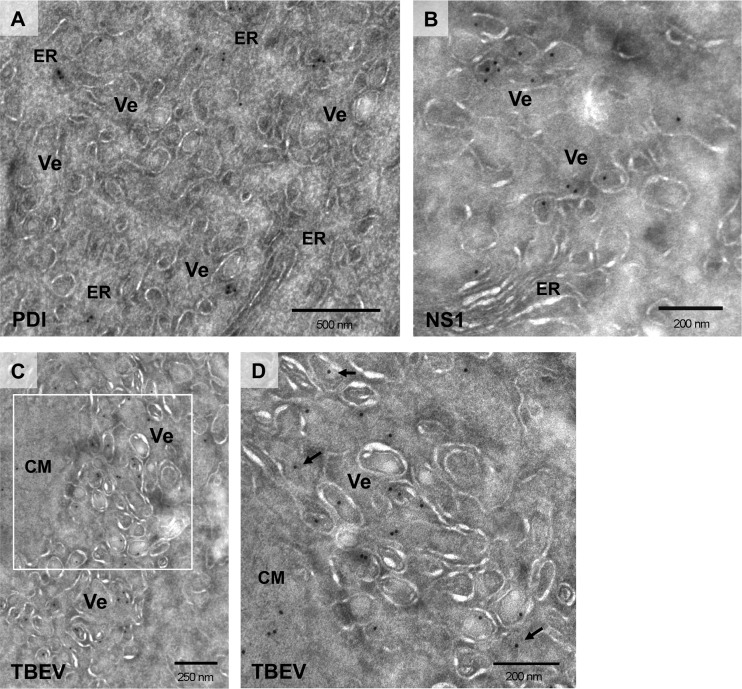

Membrane alterations observed upon transfection of MS2-tagged subgenomic replicons were then further characterized by immuno-EM (Fig. 5). As already suggested by our detailed three-dimensional analysis of replicon-induced ultrastructural changes (Fig. 4; see also Movies S3 and S4 in the supplemental material), PDI labeling clearly confirmed that TBEV-induced vesicles are part of an intricate network of rearranged intracellular membranes that originate from the ER compartment (Fig. 5A). These vesicles were labeled with anti-NS1 antibodies, again supporting their role in virus replication (Fig. 5B). Clusters of vesicles, defined as vesicle packets (14, 15, 32), could be observed in close proximity to highly rearranged membranous structures most likely representing convoluted membranes (CM), the putative sites for synthesis, and processing of the flavivirus polyprotein. As shown in Fig. 5C and D, the TBEV-specific polyclonal antiserum labeled both vesicles and CM (Fig. 5D, arrows). In addition, gold particles for the same antiserum were found also in the lumen of the ER, consistent with our previous findings on TBEV-infected cells.

Fig 5.

Immunogold EM of replicon-induced membrane alteration. BHK21-EYFP-MS2nls cells were electroporated with TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 and fixed 24 h after, and thawed cryosections were labeled with antibodies against PDI (A) and NS1 (B) and with the anti-TBEV serum (C and D). All images show TBEV-induced vesicles (Ve) that are specifically labeled with anti-NS1 (B) and anti-TBEV (C and D) antibodies. (D) Higher-magnification image of membrane alterations induced by replicon transfection corresponding to the boxed region in panel C. Vesicles (Ve) and convoluted membranes (CM) labeled with anti-TBEV antibodies are shown.

Replicated viral RNA is not freely diffusible in the cytoplasm.

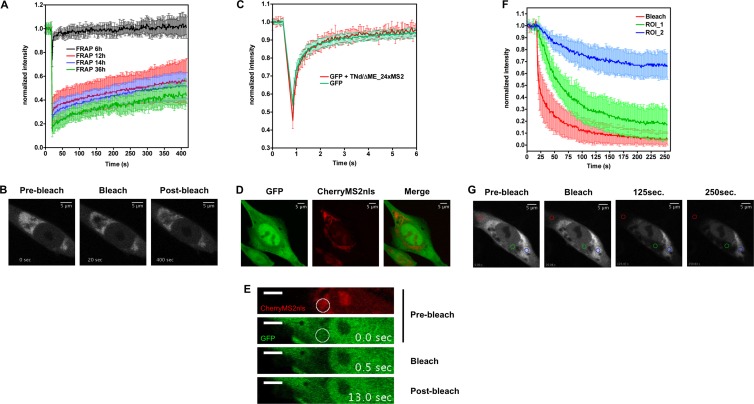

The MS2-tagging method was then further exploited to study the dynamic interchange of newly replicated TBEV RNA between MS2-defined perinuclear compartments and the cytoplasm. To this end, we took advantage of the fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) technique. FRAP is a method for measuring the mobility of fluorescent particles in living cells (33, 34). A defined portion of the system containing mobile fluorescent molecules is exposed to a brief and intense focused laser beam, thereby causing irreversible photochemical bleaching of the fluorophore in that region. The subsequent kinetics of fluorescence recovery in the bleached region, which results from transport of fluorescent proteins into the bleached area from nonirradiated regions of the cell, as well as transport of bleached fluorescent proteins out of the bleached area, provides a quantitative measure of the mobility of the protein of interest. If the fluorescent protein cannot move or is bound to an immobile substrate, the recovery of fluorescence will not reach the prebleach values showing the so-called immobile fraction. In our case, the fluorescent protein is the MS2 phage coat protein fused to EYFP. TBEV-replicated RNA carrying an array of MS2 binding sites previously characterized in our laboratory is detected by high-affinity specific interaction between the RNA stem-loops and the fluorescently labeled MS2 protein (19, 34). The viral RNA is continuously synthesized by the viral polymerase and should be able to diffuse in the cytoplasm in complex with EYFP-MS2 unless bound to an immobile structure or limited in its movements by physical barriers. As shown in Fig. 6A and B and Movie S5 in the supplemental material, BHK-21 cells expressing the TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 replicon RNA and EYFP-MS2 were subjected to FRAP analysis at different time points. Full recovery of the signal within a few seconds was observed 6 h after electroporation, indicating free mobility of EYFP-MS2 at early time points of replicon amplification. In contrast, 12 h after transfection and at later time points, fluorescence recovery was severely impaired. Time points between 12 and 36 h showed very similar recovery profiles, with an initial recovery that quickly tails off and never reaches prebleach values, indicative of the presence of a relevant immobile fraction. The initial portion of the recovery curve represents the unbound EYFP-MS2 that remains free to diffuse in the bleached area. At later time points, the amount of free EYFP-MS2 is reduced, being sequestered by the increasing amount of replicated RNA (compare the red curve in Fig. 6A taken at 12 h postelectroporation [hpe] to the blue and green curves taken at 24 to 36 hpe, respectively). These data suggest that the spatial constraints are established early and maintained thereafter. These results can be interpreted in different ways that were addressed as follows.

Fig 6.

TBEV-replicated RNA is not freely diffusible in the cytoplasm. (A) Analysis of TBEV RNA dynamics by FRAP time course. BHK-21 cells were electroporated with the TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 replicon RNA together with a vector expressing EYFP-MS2. At the indicated time points postelectroporation, the fluorescence recovery of the EYFP-MS2 protein in the area of bleaching was analyzed. The graph shows values of fluorescence intensity normalized to the prebleach values and corrected for the loss of fluorescence due to the imaging procedure (34, 36, 55). Data represent the averages of acquisitions from at least 10 cells ± standard deviations. (B) Image sequence from a FRAP experiment performed in BHK-21 cells 14 h after electroporation (29.25 by 29.25 μm). The bright perinuclear region represents the subcellular compartment into which replicated viral RNA is clustered and where ROIs were drawn. Times were collected before bleaching (prebleach, 0 s), immediately after the bleaching (bleach, 20 s), and at 400 s after the bleaching event (postbleach). A movie is also available as supporting information (see Movie S5 in the supplemental material). (C) Analysis of GFP mobility within the replication compartment. BHK-21 cells were electroporated with a vector expressing CherryMS2nls, to mark the RC, and with a GFP-expressing plasmid (pEGFP-N1), both in the presence (red line, GFP and TNd/ΔME_24×MS2) and in the absence (green line, GFP) of the TBEV replicon RNA. After 24 h, GFP kinetics was investigated by FRAP. In the graph, the recovery curves of the GFP protein in the two different experimental conditions are compared. The values of fluorescence intensity are normalized to the prebleach values and corrected for the loss of fluorescence due to the imaging procedure as already described. Data represent the averages of acquisitions from 10 cells ± standard deviations. (D) Representative image of BHK-21 cells transfected with GFP and CherryMS2nls in the presence of the TBEV replicating RNA. A z-projection of 41 images 0.5 μm apart is shown. (E) Image sequence from the FRAP experiment described in panel C (36.56 by 7.14 μm). Top, prebleach stacks in both channels (0 s). The circle indicates the area of bleach chosen in the RC marked by CherryMS2nls. Middle, time point immediately after the bleaching event (0.5 s); bottom, postbleach stack (13 s). A video is also available as supporting information (see Movie S6 in the supplemental material). (F) BHK-21 cells were electroporated with the TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 replicon RNA together with a vector expressing EYFP-MS2. After 24 h, viral RNA release from the RC was monitored by FLIP. (G) Selected images from a FLIP experiment are shown (36.56 by 36.56 μm). The region for bleaching (red circle in the bottom panels) was chosen in the cytoplasm away from the clustered TBEV RNA. Loss of fluorescence was then measured in the cytoplasm both within (blue circle, ROI_1) and outside (green circle, ROI_2) the RC. In the top graph, the loss in fluorescence intensity within the three different ROIs (bleach; ROI_1 and ROI_2) is compared. Data are normalized as described for panel A and represent the averages of acquisitions from 10 cells ± standard deviations. A video is also available as supporting information (see Movie S7 in the supplemental material).

The first possibility is that the replicated viral RNA is secluded into compartments that are not accessible by the EYFP-MS2. To address this assumption, we exploited the red-shifted variant Cherry-MS2nls to mark viral RNA while the mobility of free green fluorescent protein (GFP) was monitored by FRAP as previously described (21, 34–36). As shown in Fig. 6C, D, and E and Movie S6 in the supplemental material, mobility of GFP within the compartment did not differ significantly from the free mobility of the protein in the cytoplasm. The second possibility is that the viral RNA is only slowly or not at all replicated, resulting in little or no substrate available for free EYFP-MS2. However, bleaching did not affect virus replication (data not shown), and we have earlier shown that replicated viral RNA accumulates continuously up to 72 h posttransfection (19, 31). Therefore, we can exclude that the RCs are inactive with respect to replication. The third possibility is that a slow release of replicated viral RNA bound to bleached EYFP-MS2 residing in the region of interest (ROI) results in an increase of the immobile fraction in the FRAP experiment. To address such a release of replicated, MS2-tagged, viral RNA from this region, we depleted fluorescent EYFP-MS2 from the cytoplasm and measured loss of florescence at the compartment. This approach is called fluorescence loss in photobleaching (FLIP) and is complementary to FRAP (37, 38). As shown in Fig. 6F and Movie S7 in the supplemental material, we chose a region for bleaching in the cytoplasm distant from the MS2-enriched perinuclear compartment and measured loss of fluorescence at a site in the cytoplasm as well as within regions of EYFP-MS2 accumulation in order to assess RNA exchange. Both sites were chosen approximately at the same distance from the bleaching area. After each bleaching, the intensity of fluorescence was measured in every ROI. In principle, each mobile fluorescent molecule that diffuses at the bleaching site will be irreversibly bleached. Hence, regions of freely mobile proteins will be losing fluorescence quickly, whereas regions where the proteins are immobile or secluded into membrane compartments will resist bleaching. This kind of measurements clearly showed that fluorescent TBEV RNA-bound EYFP-MS2 (blue line) is depleted less efficiently than freely diffusible EYFP-MS2 (green line). Importantly, as observed for the FRAP experiments (Fig. 6A) where the immobile fraction decreased at later time points, immobilization of trapped TBEV RNA within the MS2-defined compartment is not complete, since 30% depletion is observed after 4 min of FLIP. This clearly points toward a certain degree of TBEV RNA exchange between the compartments and the cytoplasm.

Free diffusion of viral RNA within interconnected regions of virus-induced membrane alterations.

Finally, we wanted to investigate the dynamic interchange of TBEV RNA within the area enriched for the EYFP signal. To this end, we took again advantage of the EYFP-MS2nls reporter that, in the presence of replicating TNd/ΔME_24×MS2, accumulates efficiently in the cytoplasm against a dark background, greatly enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (Fig. 4A). This strategy is also particularly useful when doing dynamic studies, because it allows to selectively measure viral RNA kinetics without taking into account free diffusion of unbound MS2 proteins in the cytoplasm. We designed a FLIP experiment where the bleached area is located within perinuclear regions of EYFP-MS2 accumulation (Fig. 7A, red circle, bottom panels). If the tagged viral RNAs were all interconnected, continuous bleaching would have resulted in depletion of fluorescence from the entire compartment. Conversely, as shown in Fig. 7A and Movie S8 in the supplemental material, depletion of fluorescence was restricted to a portion of the compartment, defined as ROI_1 in Fig. 7A, leaving the rest unaffected. This experiment indicates that the perinuclear region, where replication of TBEV is likely to occur, is not just a continuous network of virus-induced membrane alterations but is rather composed of physically separated subcompartments. Within a subcompartment, the viral RNA is able to freely diffuse (compare decay of ROI_1 in Fig. 7A with ROI_1 in Fig. 6F), indicating that most likely the RNA is not completely associated to membranes.

Fig 7.

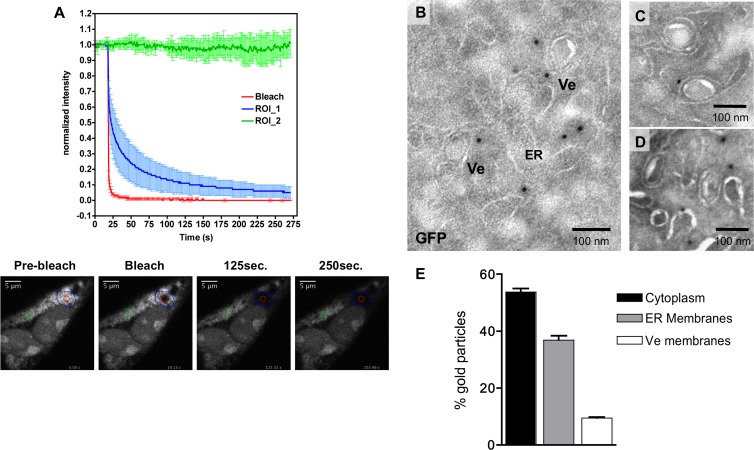

TBEV replication compartments are organized in discrete clusters. (A) BHK-21 cells were electroporated with the TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 replicon RNA and with the EYFP-MS2nls reporter. At 24 h after transfection, viral RNA trafficking within the RC was analyzed by FLIP. For this purpose, as shown in the bottom images (29.25 by 29.25 μm), the area of bleaching (red circle) was located inside the compartment. Loss of fluorescence was then measured in two different regions, one surrounding the bleaching area (blue region; ROI_1) and the other one more distant (green circle; ROI_2). The top panel compares the loss of fluorescence curves of the three selected ROIs. Data are normalized as already described and represent the average of acquisitions from 10 cells ± standard deviation. A video is also available as supporting information (see Movie S8 in the supplemental material). (B) BHK21-EYFP-MS2nls cells were electroporated with TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 and fixed 24 h after, and thawed cryosections were immunogold labeled with antibodies against GFP. Selected examples of the different situations are shown in panels C and D. (E) Quantification of GFP-labeled EM cryosections prepared as described in Fig. 7B. Counting was performed in triplicate, measuring the distribution of >100 gold particles for each grid. Data are plotted as percentages ± SD.

To unambiguously identify the subcellular localization of newly synthesized viral genomes, we selectively labeled the MS2 protein bound to TBEV RNA by using antibodies specific to the fluorescent tag. BHK-21 cells transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing EYFP-MS2nls were either mock electroporated or electroporated with the TNd/ΔME_24×MS2 replicon RNA. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were fixed and processed for immuno-EM as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 7, immunogold-labeled TBEV RNA specifically localized in the cytoplasm of TNd/ΔME_24×MS2-transfected cells, while, as expected, only nuclear MS2 labeling could be detected in mock-transfected cells (data not shown). Strikingly, detailed analysis of GFP-labeled cryosections revealed that more than 50% of the gold particles localized in the cytosol, frequently surrounding virus-induced vesicles (Fig. 7E). In addition, particles associated or in close proximity to ER-derived membranes (∼ 35%), as well as adjacent to vesicle-surrounding membranes (∼ 9%), were also observed. To the contrary, labeled TBEV RNA was never detected within the lumen of the vesicles, indicating that either the EYFP-MS2nls protein is too big to translocate into the vesicle or that actively replicating viral RNA is part of a huge protein/RNA complex that shields the RNA from the MS2 protein and/or anti-GFP antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Flaviviruses hijack cytoplasmic membranes in order to build functional sites for protein synthesis, processing, and RNA replication (7, 39–42). These sites, generally defined as replication compartments, are required to efficiently coordinate different steps of the viral life cycle and to protect replicating RNA from innate immunity surveillance (8–10). Over the last few years, several electron microscopy studies have revealed important information about the ultrastructural organization of these sophisticated intracellular membrane compartments (11, 12, 28). However, this information is rather static and does not provide insights into intracellular trafficking of proteins and viral RNA. In this work, we have combined high-resolution ET and immuno-EM with live-cell imagining studies of TBEV RNA dynamics to provide the first comprehensive picture of the spatiotemporal organization of the flaviviral RC.

Our detailed 3D ultrastructural analysis clearly shows that TBEV infection triggers a remarkable alteration of intracellular membranes (Fig. 2). These virus-induced membranes are derived from the ER since they contain viral proteins and the ER-resident chaperone PDI (Fig. 1). PDI did not directly label the vesicles (Fig. 3A), indicating that this protein is not recruited but most likely excluded from virus-induced membranes, as observed for DENV-induced vesicles (11). Interestingly, we consistently observed packets of vesicles with a diameter of about 80 nm that appear as invaginations of the ER within a highly organized network of interconnected membranes (Fig. 2A and B; see also Movies S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Attempts to label vesicles with antibodies recognizing dsRNA were ambiguous; although we detected immunogold labeling within the vesicles, the signal appeared to be unspecific (data not shown). Nevertheless, labeling of the vesicles with antibodies against the TBEV NS1 protein (Fig. 3B, C, and D) supports the hypothesis that these structures correspond to sites of virus replication. NS1 is an essential gene and modulates early viral RNA replication (13, 43), possibly through its ability to regulate negative-strand synthesis of viral RNA (44) and/or by interacting with NS4B (45). NS1 is located in the ER lumen and is associated with the outer side of the replication vesicles through interaction with other transmembrane viral proteins. Localization of DENV NS1 at replication vesicles was reported by Mackenzie et al. (13) and more recently by Welsch et al. (11). Finally, immunoprecipitation of dsRNA intermediates was shown to contain NS1 in addition to NS5, confirming previous cosedimentation data (46, 47). Therefore, NS1 can be considered a bona fide marker for replication sites. The observation that NS1 is associated to other compartments in addition to replication vesicles may reflect its involvement in different steps of the viral life cycle, beyond RNA replication.

Approximately half of the vesicles showed a single pore-like connection to the cytoplasm. There might be several explanations for this observation. Besides technical problems that may not allow clear detection of pores in all vesicles, there could be a dynamic life cycle of virus-induced vesicles, from their formation, function in replication with a pore connection, and eventual late step where the vesicles are not connected with the cytosol by the pore anymore. This pore likely allows recruitment of cellular cofactors to active sites of virus replication as well as for the release of newly synthesized viral RNA to be used for translation and assembly (Fig. 2D). However, although the vesicles were frequently closely associated, we could never detect direct connections between neighboring vesicles in the same packet, as described for Kunjin virus and more recently also for the naturally attenuated tick-borne LGTV (12, 28). This discrepancy might be due to differences in the sample preparation. Alternatively, it might implicate that the architecture of flaviviral RCs slightly changes based on the specific virus and/or cell line used for the analysis.

We also often observed newly assembled virions sharing the same ER lumen with putative replicative vesicles, suggesting that replication and assembly sites are located in very close proximity. Given the absence of pore-like openings directly connecting vesicles with the ER lumen, it is likely that, once synthesized, the viral RNA is released via the pore to the cytosolic side of these invaginations. The basic C protein would then interact with progeny RNA genomes to form a nucleocapsid that buds back to the lumen of the ER, acquiring the viral envelope. Thereafter, immature viral particles would be either stored in clusters within dilated ER cisternae (Fig. 2A) or transported through the cellular secretory pathway (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material), where maturation occurs, in order to be released to the extracellular milieu (48, 49).

In this study, we also compared ultrastructural alterations induced by virus infection with those associated with the replication of MS2-tagged TBEV subgenomic replicons. As observed upon TBEV infection, dramatic reorganization of intracellular membranes with the appearance of single membrane vesicles could be detected in the perinuclear region of the cell. Although ER tubules hosting replicon-induced vesicles appeared fragmented and smaller than those observed in virus-infected cells, vesicles were similar in size, and our detailed tomographic analysis revealed that they also originated from the ER and were connected to the cytoplasm via pore-like channels. Interestingly, at variance with virus-infected cells, replicon-induced vesicles did not accumulate in packets but were rather dispersed through the cytoplasm as one or few invaginations of the ER membrane (Fig. 4; see also Movies S3 and S4 in the supplemental material). We also observed a higher fraction of vesicles with pores in replicon-transfected cells. However, the latter observation could be simply related to a better accessibility of dispersed vesicles during ET. These data suggest that replicons, despite the induction of massive ER rearrangements, are less efficient at forming vesicles, which is consistent with the lower level of viral replication previously reported (31, 50, 51). The induction of membrane rearrangements could be due to the altered expression or regulation of viral proteins resulting from the electroporation of large amounts of genomic RNA. For example, it has been shown that the NS4A protein of mosquito-borne KUNV and DENV viruses possesses the intrinsic capacity to induce membrane rearrangements similar to those induced upon virus infection (52, 53). A similar role for TBEV NS4A remains to be clarified.

When we investigated the mobility of viral RNA by FRAP, we found a consistent delay of the recovery of fluorescence within perinuclear regions of EYFP-MS2 accumulation (Fig. 6A). In contrast, GFP did not show significant differences of mobility within the cytosol compared to that within TBEV-induced replication compartments that are marked with cherry-MS2nls (Fig. 6C), suggesting that these compartments are open to the cytosol and allow exchange of proteins. Interestingly, recovery after 36 h did not differ significantly from that at 12 h after replicon transfection. Although we cannot formally exclude that replication rates slow down at late time points, thus masking an increase of recovery in the FRAP curve due to an increased permeability, we can assume that the mobility of viral RNA is similar at early and late time points. In other terms, at later time points there is not a massive disruption or reorganization of these membranous compartments compatible with the liberation of viral RNA. Free accessibility of the fluorescent MS2 concomitant with a slow recovery after photobleaching within the compartment suggests an impaired movement of the genomic RNA out of this area. This could be coupled with a low rate of viral RNA biogenesis and/or with the association of a fraction of the viral RNA to polysomes on ER membranes. To address this hypothesis, we performed a FLIP experiment, and we directly measured trafficking of viral RNA between cytosol and sites of virus replication (Fig. 6F). Strikingly, we could observe a slow release of replicated RNA from the compartment.

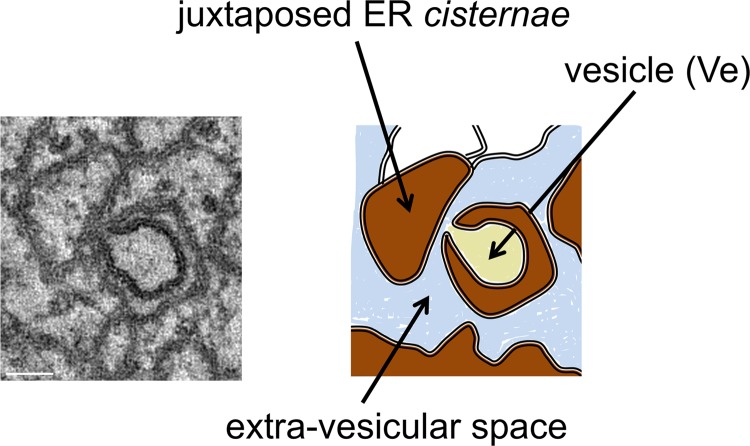

Another important observation relates to the mobility of tagged viral RNA within MS2-defined regions of the cytoplasm. Previous FRAP studies performed with components of the HCV replication complex NS4B and NS5A showed that the internal architecture of the membranous web is relatively static, with limited exchange of viral nonstructural proteins between neighboring factories (17, 18, 54). In the present study, for the first time, we monitored viral RNA dynamics within perinuclear regions of virus replication. By using continuous bleaching of MS2 fluorescence in the region where the RNA is clustered, we could observe a fast depletion of fluorescence, consistent with a high mobility of the viral RNA (Fig. 7A; see Movie S8 in the supplemental material). Mobility within this area was indeed higher than mobility between the compartment and the cytosol, confirming that a physical impediment restricts viral RNA egress rather than an intrinsic slow mobility of the viral RNP (compare the blue lines in Fig. 6F and 7A). However, depletion of fluorescence was clearly restricted only to a discrete region in the cluster, leading us to the conclusion that these TBEV-induced compartments are partitioned with respect to viral RNA mobility. In agreement with this finding, specific labeling of the newly replicated RNA clearly revealed a high proportion of labeled MS2-tagged RNA genomes localized in the cytosolic space surrounding TBEV-induced membrane alterations (Fig. 7E). Therefore, we propose that upon synthesis within ER-derived vesicles, progeny genomes must be released to a larger virus-induced extravesicular subcompartment where RNA translation and virus assembly occur. This subcompartment would be full of viral RNA that travels from replication vesicles to the virion assembly sites and is connected to the cytoplasm (Fig. 8). Such an extremely organized architecture would certainly help in coordinating genomic RNA recruitment for translation and/or packaging.

Fig 8.

Model of TBEV-induced membrane alterations. Left, slice of the dual-axis tomogram shown in Fig. 4B; right, two-dimension schematic model of the possible organization of TBEV replication compartments. TBEV replication leads to the formation of a highly organized network of interconnected and juxtaposed ER membranes in the perinuclear region of the cells. This compartment is composed of vesicles (Ve; in light yellow) connected to the cytoplasm via pore-like channels, of dilated ER cisternae (in brown), and of a cytoplasmic extravesicular space (in light blue). Progeny viral RNAs are synthesized within the lumen of these ER invaginations and are then extruded through the pore into the cytoplasmic extravesicular space. Once released into this area, viral RNAs are available for downstream assembly into new viral particles that bud back into the lumen of ER cisternae of infected cells (Fig. 2). Alternatively, these RNAs may be engaged in further rounds of translation and replication.

In conclusion, we generated a high-resolution structure of the three-dimensional organization of the TBEV-induced replication compartment. In addition, by exploiting the MS2-tagged replicon system, we could combine structural information with dynamic data of newly replicated TBEV-RNA within functional intracellular compartments, providing new insights into the spatiotemporal organization of flavivirus replication compartments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Electron Microscopy Core Facility (EMCF) at the University of Heidelberg and the EM Facility at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL; Heidelberg) for providing access to their equipment, expertise, and technical support. We also thank Anil Kumar for the expert help in handling lentiviral vectors and for useful discussions.

L.M. benefited from a short-term EMBO fellowship (ASTF 217-2012). Work on flaviviruses in A.M.'s laboratory is supported by the Beneficientia Stiftung. R.B. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 638, TPA5, TRR83, TP13).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 April 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.03456-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gritsun TS, Lashkevich VA, Gould EA. 2003. Tick-borne encephalitis. Antiviral Res. 57:129–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lindquist L, Vapalahti O. 2008. Tick-borne encephalitis. Lancet 371:1861–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mansfield KL, Johnson N, Phipps LP, Stephenson JR, Fooks AR, Solomon T. 2009. Tick-borne encephalitis virus—a review of an emerging zoonosis. J. Gen. Virol. 90:1781–1794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gubler DJ, Kuno G, Markoff L. 2007. Flaviviruses, p 1153–1252 In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA. (ed), Fields virology, fifth ed Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lindenbach BD, Thiel HJ, Rice CM. 2007. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 1101–1152 In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA. (ed), Fields virology, fifth ed Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fernandez-Garcia MD, Mazzon M, Jacobs M, Amara A. 2009. Pathogenesis of flavivirus infections: using and abusing the host cell. Cell Host Microbe 5:318–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller S, Krijnse-Locker J. 2008. Modification of intracellular membrane structures for virus replication. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:363–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miorin L, Albornoz A, Baba MM, D'Agaro P, Marcello A. 2012. Formation of membrane-defined compartments by tick-borne encephalitis virus contributes to the early delay in interferon signaling. Virus Res. 163:660–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Overby AK, Popov VL, Niedrig M, Weber F. 2010. Tick-borne encephalitis virus delays interferon induction and hides its double-stranded RNA in intracellular membrane vesicles. J. Virol. 84:8470–8483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoenen A, Liu W, Kochs G, Khromykh AA, Mackenzie JM. 2007. West Nile virus-induced cytoplasmic membrane structures provide partial protection against the interferon-induced antiviral MxA protein. J. Gen. Virol. 88:3013–3017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Welsch S, Miller S, Romero-Brey I, Merz A, Bleck CK, Walther P, Fuller SD, Antony C, Krijnse-Locker J, Bartenschlager R. 2009. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe 5:365–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gillespie LK, Hoenen A, Morgan G, Mackenzie JM. 2010. The endoplasmic reticulum provides the membrane platform for biogenesis of the flavivirus replication complex. J. Virol. 84:10438–10447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mackenzie JM, Jones MK, Young PR. 1996. Immunolocalization of the dengue virus nonstructural glycoprotein NS1 suggests a role in viral RNA replication. Virology 220:232–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA, Jones MK, Westaway EG. 1998. Subcellular localization and some biochemical properties of the flavivirus Kunjin nonstructural proteins NS2A and NS4A. Virology 245:203–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Westaway EG, Mackenzie JM, Kenney MT, Jones MK, Khromykh AA. 1997. Ultrastructure of Kunjin virus-infected cells: colocalization of NS1 and NS3 with double-stranded RNA, and of NS2B with NS3, in virus-induced membrane structures. J. Virol. 71:6650–6661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moradpour D, Evans MJ, Gosert R, Yuan Z, Blum HE, Goff SP, Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. 2004. Insertion of green fluorescent protein into nonstructural protein 5A allows direct visualization of functional hepatitis C virus replication complexes. J. Virol. 78:7400–7409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jones DM, Gretton SN, McLauchlan J, Targett-Adams P. 2007. Mobility analysis of an NS5A-GFP fusion protein in cells actively replicating hepatitis C virus subgenomic RNA. J. Gen. Virol. 88:470–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wolk B, Buchele B, Moradpour D, Rice CM. 2008. A dynamic view of hepatitis C virus replication complexes. J. Virol. 82:10519–10531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miorin L, Maiuri P, Hoenninger VM, Mandl CW, Marcello A. 2008. Spatial and temporal organization of tick-borne encephalitis flavivirus replicated RNA in living cells. Virology 379:64–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koutsoudakis G, Kaul A, Steinmann E, Kallis S, Lohmann V, Pietschmann T, Bartenschlager R. 2006. Characterization of the early steps of hepatitis C virus infection by using luciferase reporter viruses. J. Virol. 80:5308–5320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boireau S, Maiuri P, Basyuk E, de la Mata M, Knezevich A, Pradet-Balade B, Backer V, Kornblihtt A, Marcello A, Bertrand E. 2007. The transcriptional cycle of HIV-1 in real-time and live cells. J. Cell Biol. 179:291–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mandl CW, Ecker M, Holzmann H, Kunz C, Heinz FX. 1997. Infectious cDNA clones of tick-borne encephalitis virus European subtype prototypic strain Neudoerfl and high virulence strain Hypr. J. Gen. Virol. 78(Part 5):1049–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Orlinger KK, Hoenninger VM, Kofler RM, Mandl CW. 2006. Construction and mutagenesis of an artificial bicistronic tick-borne encephalitis virus genome reveals an essential function of the second transmembrane region of protein E in flavivirus assembly. J. Virol. 80:12197–12208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Griffiths G, Simons K, Warren G, Tokuyasu KT. 1983. Immunoelectron microscopy using thin, frozen sections: application to studies of the intracellular transport of Semliki Forest virus spike glycoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 96:466–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116:71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Westaway EG, Khromykh AA, Mackenzie JM. 1999. Nascent flavivirus RNA colocalized in situ with double-stranded RNA in stable replication complexes. Virology 258:108–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mackenzie JM, Jones MK, Westaway EG. 1999. Markers for trans-Golgi membranes and the intermediate compartment localize to induced membranes with distinct replication functions in flavivirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 73:9555–9567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Offerdahl DK, Dorward DW, Hansen BT, Bloom ME. 2012. A three-dimensional comparison of tick-borne flavivirus infection in mammalian and tick cell lines. PLoS One 7:e47912 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kopek BG, Perkins G, Miller DJ, Ellisman MH, Ahlquist P. 2007. Three-dimensional analysis of a viral RNA replication complex reveals a virus-induced mini-organelle. PLoS Biol. 5:e220 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iacono-Connors LC, Smith JF, Ksiazek TG, Kelley CL, Schmaljohn CS. 1996. Characterization of Langat virus antigenic determinants defined by monoclonal antibodies to E, NS1 and preM and identification of a protective, non-neutralizing preM-specific monoclonal antibody. Virus Res. 43:125–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoenninger VM, Rouha H, Orlinger KK, Miorin L, Marcello A, Kofler RM, Mandl CW. 2008. Analysis of the effects of alterations in the tick-borne encephalitis virus 3′-noncoding region on translation and RNA replication using reporter replicons. Virology 377:419–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA, Westaway EG. 2001. Stable expression of noncytopathic Kunjin replicons simulates both ultrastructural and biochemical characteristics observed during replication of Kunjin virus. Virology 279:161–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Axelrod D, Koppel DE, Schlessinger J, Elson E, Webb WW. 1976. Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics. Biophys. J. 16:1055–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maiuri P, Knezevich A, Bertrand E, Marcello A. 2010. Real-time imaging of the HIV-1 transcription cycle in single living cells. Methods 53:62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Molle D, Maiuri P, Boireau S, Bertrand E, Knezevich A, Marcello A, Basyuk E. 2007. A real-time view of the TAR:Tat:P-TEFb complex at HIV-1 transcription sites. Retrovirology 4:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maiuri P, Knezevich A, De Marco A, Mazza D, Kula A, McNally JG, Marcello A. 2011. Fast transcription rates of RNA polymerase II in human cells. EMBO Rep. 12:1280–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lippincott-Schwartz J, Snapp E, Kenworthy A. 2001. Studying protein dynamics in living cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:444–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dundr M, Misteli T. 2003. Measuring dynamics of nuclear proteins by photobleaching. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 13:Unit 13.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mackenzie J. 2005. Wrapping things up about virus RNA replication. Traffic 6:967–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. den Boon JA, Diaz A, Ahlquist P. 2010. Cytoplasmic viral replication complexes. Cell Host Microbe 8:77–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ahlquist P. 2006. Parallels among positive-strand RNA viruses, reverse-transcribing viruses and double-stranded RNA viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:371–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Novoa RR, Calderita G, Arranz R, Fontana J, Granzow H, Risco C. 2005. Virus factories: associations of cell organelles for viral replication and morphogenesis. Biol. Cell 97:147–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Khromykh AA, Sedlak PL, Guyatt KJ, Hall RA, Westaway EG. 1999. Efficient trans-complementation of the flavivirus kunjin NS5 protein but not of the NS1 protein requires its coexpression with other components of the viral replicase. J. Virol. 73:10272–10280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. 1997. Trans-complementation of yellow fever virus NS1 reveals a role in early RNA replication. J. Virol. 71:9608–9617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Youn S, Li T, McCune BT, Edeling MA, Fremont DH, Cristea IM, Diamond MS. 2012. Evidence for a genetic and physical interaction between nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS4B that modulates replication of West Nile virus. J. Virol. 86:7360–7371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chu PW, Westaway EG. 1987. Characterization of Kunjin virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: reinitiation of synthesis in vitro. Virology 157:330–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grun JB, Brinton MA. 1987. Dissociation of NS5 from cell fractions containing West Nile virus-specific polymerase activity. J. Virol. 61:3641–3644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mackenzie JM, Westaway EG. 2001. Assembly and maturation of the flavivirus Kunjin virus appear to occur in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and along the secretory pathway, respectively. J. Virol. 75:10787–10799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lorenz IC, Kartenbeck J, Mezzacasa A, Allison SL, Heinz FX, Helenius A. 2003. Intracellular assembly and secretion of recombinant subviral particles from tick-borne encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 77:4370–4382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Khromykh AA, Westaway EG. 1997. Subgenomic replicons of the flavivirus Kunjin: construction and applications. J. Virol. 71:1497–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jones CT, Patkar CG, Kuhn RJ. 2005. Construction and applications of yellow fever virus replicons. Virology 331:247–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Miller S, Kastner S, Krijnse-Locker J, Buhler S, Bartenschlager R. 2007. The non-structural protein 4A of dengue virus is an integral membrane protein inducing membrane alterations in a 2K-regulated manner. J. Biol. Chem. 282:8873–8882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Roosendaal J, Westaway EG, Khromykh A, Mackenzie JM. 2006. Regulated cleavages at the West Nile virus NS4A-2K-NS4B junctions play a major role in rearranging cytoplasmic membranes and Golgi trafficking of the NS4A protein. J. Virol. 80:4623–4632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gretton SN, Taylor AI, McLauchlan J. 2005. Mobility of the hepatitis C virus NS4B protein on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and membrane-associated foci. J. Gen. Virol. 86:1415–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Phair RD, Misteli T. 2000. High mobility of proteins in the mammalian cell nucleus. Nature 404:604–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.