Abstract

Objectives

An increasingly important concern for clinicians who care for patients at the end of life is their spiritual well-being and sense of meaning and purpose in life. In response to the need for short-term interventions to address spiritual well-being, we developed Meaning Centered Group Psychotherapy (MCGP) to help patients with advanced cancer sustain or enhance a sense of meaning, peace and purpose in their lives, even as they approach the end of life.

Methods

Patients with advanced (stage III or IV) solid tumor cancers (N = 90) were randomly assigned to either MCGP or a supportive group psychotherapy (SGP). Patients were assessed before and after completing the 8-week intervention, and again 2 months after completion. Outcome assessment included measures of spiritual well-being, meaning, hopelessness, desire for death, optimism/pessimism, anxiety, depression and overall quality of life.

Results

MCGP resulted in significantly greater improvements in spiritual well-being and a sense of meaning. Treatment gains were even more substantial (based on effect size estimates) at the second follow-up assessment. Improvements in anxiety and desire for death were also significant (and increased over time). There was no significant improvement on any of these variables for patients participating in SGP.

Conclusions

MCGP appears to be a potentially beneficial intervention for patients’ emotional and spiritual suffering at the end of life. Further research, with larger samples, is clearly needed to better understand the potential benefits of this novel intervention.

Keywords: psychotherapy, meaning, spiritual well-being, palliative care, existential

Introduction

An increasingly important concern for mental health clinicians who care for patients at the end of life is their spiritual well-being and sense of meaning and purpose in life [1–4]. An Institute of Medicine (IOM) report identified spiritual well-being as one of the most important influences on patient quality of life at the end of life [5]. Our research group has demonstrated a central role for meaning, buffering against depression, hopelessness and desire for hastened death among advanced cancer patients [6–8]. Such findings suggest that non-pharmacologic, psychotherapeutic interventions need to be developed to help patients with cancer enhance their sense of meaning and purpose in life despite their illness.

There is strong evidence that group psychotherapy interventions for cancer patients are time-efficient, economical and effective in improving quality of life, reducing psychological distress, improving coping skills and reducing the distress associated with symptoms such as pain [9–13]. However, few interventions have specifically focused on existential or spiritual domains in treatment or measured the impact of treatment on such outcomes, particularly in patients with advanced cancer. Early research by Yalom, Spiegel and colleagues demonstrated that a 1-year supportive group psychotherapy (SGP), which included a focus on existential issues, decreased psychological distress and improved quality of life [14–16]. The authors concluded, based on relatively weaker findings at 4- and 8-month assessments, that ‘participation in the group over a one-year period was necessary to consolidate measurable change [15].’ Moreover, although significant improvement was noted for some of the variables studied, others (e.g. depression) were not impacted by this intervention.

Several recent studies have described short-term interventions that included a spiritual or existential component, including individually based approaches [2,3,17,18]. Lee et al. [2] described a ‘meaning-making’ intervention, based on Folkman’s theory of meaning-making as a coping strategy [19]. They randomly assigned 82 breast and colorectal patients either to a manualized 4-session meaning-making intervention or to a ‘usual care’ arm. Following treatment, they found significant differences in optimism, self-esteem and self-efficacy. However, the investigators did not examine aspects of spiritual well-being, sense of meaning, hopelessness, depression or anxiety.

Chochinov et al. [3] also developed an individualized intervention, dignity therapy, intended to address psychosocial and existential distress among terminally ill cancer patients. In an exploratory study of this brief intervention, which involves a 1 h interview that is transcribed, edited, and given to the patient, Chochinov et al. found significant reductions in suffering and depressed mood (based on single item self-report ratings), but no significant improvement in items measuring dignity, anxiety, desire for death or suicidal ideation. Moreover, the lack of a comparison group limits any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of this intervention.

Kissane et al. analyzed the impact of a group intervention for cancer patients that included existential elements [17]. They developed ‘Cognitive-Existential Group Psychotherapy’, a 2-week intervention for women with breast cancer that focused largely on cognitive reframing, problem solving, fostering hope and examining priorities for the future. They randomly assigned 303 women to this intervention plus 3 weeks of ‘relaxation classes’ or the 3-week relaxation classes alone. However, despite this unbalanced design (in terms of treatment intensity), they found no significant differences in improved psychological distress. They did report a ‘trend’ towards reduced anxiety and significantly greater satisfaction among the treatment arm but no differences in changes in depression or other measures of symptom distress.

Similarly weak results were also reported by Coward [18], who compared women with breast cancer, who had participated in an 8-week group therapy focused on ‘transcendence’ to women who participated in a support group. Although they found significant improvement for both groups on several outcome measures, there was no difference in the magnitude of change between groups on any variable, including measures specifically focused on self-transcendence and meaning. Given these results, it is unclear whether this intervention adequately addressed issues of meaning and spirituality. Moreover, they used a ‘partial’ randomized design in which most participants choose the treatment arm they preferred rather than being randomly assigned to treatment, further clouding issues of treatment utility.

Thus, despite the seeming importance of enhancing one’s sense of meaning and purpose, few clinical interventions have been developed that attempt to address this critical issue. Those interventions that have been systematically evaluated have typically shown some benefits (e.g. increased optimism, improved mood), but none have examined the impact on spiritual well-being or a sense of meaning and purpose. Moreover, little intervention research has focused on patients with advanced cancer or other terminal illnesses. In response to the need for interventions focused on enhancing spiritual well-being, we developed Meaning Centered Group Psychotherapy (MCGP) [20,21]. Grounded in Viktor Frankl’s writings, [22,23] this intervention was designed to help patients with advanced cancer sustain or enhance a sense of meaning, peace and purpose in their lives, even as they confront death. The present study examined the impact of this novel intervention on spiritual well-being, meaning and psychological distress, compared with a standardized support group utilizing a randomized, controlled design in advanced cancer patients.

Method

Participants

Patients were recruited from outpatient clinics at Memorial Hospital in New York City between July, 2002 and September, 2005. Recruitment was primarily through posted flyers or physician referral. Eligible patients were diagnosed with stage III or IV solid tumor cancers or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, ambulatory, over 18 years old, and English-speaking. Patients were excluded if they had significant cognitive impairment or psychosis (based on clinician assessment), or had physical limitations that precluded participation in an outpatient group setting. Prospective participants were informed of the risks and benefits of study participation and provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Memorial Hospital and Fordham University IRBs.

A total of 160 patients provided informed consent, but because many patients became too ill to engage in treatment or had treatment-related scheduling conflicts (e.g. chemotherapy appointments at the time group was scheduled), only 90 began treatment. There were no significant differences on demographic or illness-related variables between patients who became too ill to participate and those who began treatment; there was also no relationship between participation and whether the patient was assigned to the group they preferred. Of the 90 patients who began treatment, 49 were randomized to MCGP and 41 to SGP; 55 completed the 8-week intervention (MCGP = 35; SGP = 20), 38 of whom (MCGP = 25; SGP = 13) completed the 2-month follow-up assessment (attrition between the two post-treatment assessments was largely due to patient death or physical deterioration). Because there were no differences in demographic or illness-related characteristics across the two treatment arms, the sample description below pertains to the entire sample.

The sample was evenly divided among males (n = 44, 48.9%) and females (n = 46, 51.1%) with an average age of 60.1 years (SD = 11.8, range: 21–84) and 16.6 years of education completed (SD = 2.8). The sample was predominantly Caucasian (n = 72, 80%), with 7 African-American participants (7.8%), 4 Hispanics (4.4%) and 7 participants of other ethnic backgrounds (7.7%). Most participants (n = 57, 63.3%) were diagnosed with stage IV disease and the most common types of cancer were prostate (n = 17, 18.9%), breast (n = 14, 15.6%) colorectal (n = 8, 13.3%) and lung (n = 8, 13.3%).

Procedures

Following informed consent, patients were randomized in groups of 8–10 (a group was formed and then assigned to treatment condition); block randomization was used to insure roughly equal numbers of groups in each treatment arm. Prior to randomization, patients were asked their preference for group assignment (this information did not impact randomization, but was analyzed with regard to attrition as described below). Participants were then administered a series of self-report questionnaires (described below) prior to the first session, following the last group session, and 2 months after completing treatment. Patients were also asked several questions upon completion regarding their perceptions of the treatment.

The assessment battery included the FACIT Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWB) [24], the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) [25], the Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death (SAHD) [26], the Life Orientation Test (LOT) [27] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [28]. Each of these measures has been widely used and well-validated in terminally ill populations. Additional data gathered at baseline included demographic (e.g. age, race, education) and clinical data (e.g. cancer diagnosis, stage of disease, Karnofsky Performance Rating Scale [29]).

Meaning-centered group psychotherapy

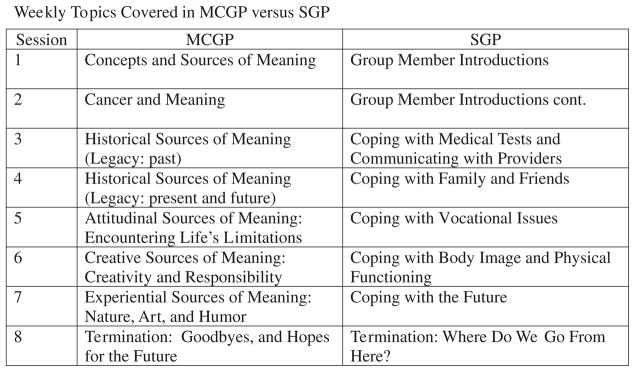

MCGP was developed by Breitbart and colleagues [20,21] to help patients with advanced cancer sustain or enhance a sense of meaning, peace and purpose in their lives even as they approach the end of life. This manualized an 8-week intervention which is influenced by the work of Viktor Frankl [22,23], and utilizes didactics, discussion and experiential exercises that focus around themes related to meaning and advanced cancer (see Figure 1). Each session addresses specific themes related to an exploration of the concepts and sources of meaning, the relationship and impact of cancer on one’s sense of meaning and identity, and placing one’s life in a historical and personal context (i.e. understanding one’s ‘legacy’). For example, for Session 3, to address the historical context of meaning, patients are asked to reflect on their life and identify ‘the most significant memories, relationships, traditions, etc., that have made the greatest impact on who you are today’. During Session 5, to explore attitudinal sources of meaning, patients participated in an experiential exercise where they are asked to respond to questions like ‘What would you consider a good or meaningful death? How can you imagine being remembered by your loved ones?’ Although the focus of each session is on issues of meaning and purpose in life in the face of advanced cancer and a limited prognosis, elements of support and expression of emotion are inevitable in the context of each group session (but limited by the focus on experiential exercises, didactics and discussions related to themes focusing on meaning).

Figure 1.

Weekly topics covered in MGGP versus SGP

All Meaning-Centered groups were conducted by either a psychiatrist or a clinical psychologist, all with experience treating patients with cancer; groups were co-led by a second doctoral-level psychologist or psychology doctoral student. Group facilitators (n = 6) underwent an extensive training in MCGP (approximately 24–28 h of didactic and observational training) prior to the start of the study and received supervision from the developer of the intervention. Because group facilitators typically participated in only 2 or 3 groups, and worked in various combinations with one another, it was not possible to assess whether any differences existed across facilitators.

Supportive psychotherapy

The supportive psychotherapy intervention (SGP) utilized as the comparison was based on the model developed by Cain et al. [30] and manualized by Payne et al. [31]. The eight weekly 90-min sessions focused on discussion of issues themes that emerge for patients coping with cancer. Utilizing a supportive approach, therapists focused on encouraging patients to share concerns related to the cancer diagnosis and treatment, to describe their experiences and emotions related to these experiences, voice problems that they have in coping with cancer, and offer support and advice to other group members. Groups were led by a clinical psychologist or licensed social worker, with a social worker or psychology doctoral student co-therapist; MCGP and SGP facilitators had comparable levels of experience and training in group psychotherapy and treatment of patients with cancer. Group facilitators (n = 8) underwent an extensive training in SGP (approximately 20–28 h) prior to the study and received supervision from the developer of the intervention.

Adherence to treatment format

All group sessions were audiotaped and a random sample of these tapes was reviewed in order to rate adherence to the prescribed treatment. In order to prevent ‘bleed’ across conditions, facilitators were trained and conducted sessions exclusively in only one of the two-study interventions. In addition, following completion of the intervention, patients were asked three questions designed to assess their perception of the content of the group they participated in (a) ‘How much did this group focus on providing support from other cancer patients?’ (b) ‘How much did this group focus on talking about your feelings about cancer?’ and (c) ‘How much did this group focus on finding a sense of meaning and purpose in life despite having cancer?’ These questions were rated on a 0–4 scale where 0 corresponded to ‘Not At All’ and 4 to ‘Very Much’. There we no significant differences (p>0.05) between treatment arms for the first two questions (Focus on Support: MCGP = 3.6, SGP = 3.2; Talking about Feelings: MCGP = 3.8, SGP = 3.5), but MCGP participants were significantly more likely than SGP participants to report a focus on finding a sense of meaning (MCGP = 3.8, SGP = 2.5), t = 2.35, p = 0.03.

Statistical analysis

The initial analysis of treatment effects was conducted within treatment groups, using matched t-tests to estimate the magnitude of change in spiritual/psychological well-being over time for each treatment arm. We subsequently used a series of repeated measures ANOVA to evaluate whether the treatment effects observed differed across the two groups. Post hoc tests were used to break down the three time points (pre-intervention, post-intervention and follow-up), by contrasting pre-intervention and post-intervention, and post-intervention and follow-up. Descriptive analyses and chi-square tests of association were used as appropriate to analyze sample characteristics (e.g. attrition rates across treatment arm). Because no a priori threshold existed for identifying ‘improvement’ on many of the study outcome measures (e.g. spiritual well-being, hopelessness, desire for hastened death), and participants were not selected based on meeting a threshold level of distress, intent-to-treat analyses were not feasible.

Results

Attrition and completion

Attrition was evaluated first as the proportion of patients who remained in the group throughout the 8-week intervention period (i.e. were available to provide post-intervention data), and second by comparing the number of sessions attended across the two interventions. Participants in MCGP attended significantly more sessions than SGP participants; MCGP: 6.6 (SD = 1.6), SGP: 4.5 (SD = 2.4), t = 5.10, p<0.0001. Of 49 individuals who began MCGP, 17 (34.7%) attended all 8 scheduled sessions and 40 (81.6%) attended 6 or more. Of the 41 individuals who began SGP, only 9 (21.9%) attended all 8 sessions and 13 (31.7%) attended 6 or more. However, the proportion of patients attending all 8 sessions did not differ significantly, 34.7% for MCGP versus 21.9% for SPT; χ2 = 1.76, p = 0.18. Attendance was significantly, albeit modestly associated with overall physical functioning, r = −0.28, p = 0.04, with physically sicker patients attending more sessions.

Because patient preferences for MCGP versus SGP might impact attrition and attendance, we analyzed concordance between pre-treatment preferences and group assignment. Of the 90 patients who began treatment, 80 had expressed a preference prior to randomization; 57 (71.3%) preferred MCGP and 23 (28.8%) preferred SGP. There was no relationship between assignment to the ‘preferred’ treatment arm and attendance, as participants assigned to the preferred treatment attended an average of 6.0 sessions compared with 5.2 sessions for those who were assigned to the non-preferred arm, t = 1.49, p = 0.14. Unfortunately, reasons for attrition were not systematically elicited, in part because ‘drop out’ was often unclear (i.e. participants may have indicated an intent to return to group despite failing to do so).

Impact of treatment on spiritual well-being and meaning

In order to analyze the impact of treatment on spiritual well-being and meaning, we utilized matched t-tests comparing responses with the FACIT SWB before and after treatment within each treatment arm (see Tables 1 and 2). For participants in MCGP, the strongest treatment effects were observed for the SWB total score and Meaning/Peace subscale (see Table 1). Average increases from pre- to post-treatment were substantial and statistically significant for SWB total scores, t(36) = 4.38, p<0.0001 and the Meaning/Peace subscale, t(36) = 4.51, p<0.0001, although more modest (although still significant) for the Faith subscale, t(36) = 2.44, p = 0.02. Participants in SGP did not demonstrate any significant change in spiritual well-being over time (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Changes in spiritual well-being and psychological functioning following MCGP

| M Pre | M Post | d | p | M F/U | d | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual well-being | |||||||

| FACIT total | 2.06 | 2.53 | 0.72 | 0.0001 | 2.80 | 1.46 | 0.0001 |

| Meaning/Peace | 2.28 | 2.79 | 0.74 | 0.0001 | 3.21 | 1.45 | 0.0001 |

| Faith | 1.60 | 1.99 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 2.01 | 0.89 | 0.006 |

| Psychological functioning | |||||||

| Depression | 14.73 | 15.35 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 12.48 | 0.33 | 0.24 |

| Hopelessness | 6.76 | 5.81 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 5.92 | 0.52 | 0.08 |

| Desire for death | 4.59 | 3.70 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 3.64 | 0.63 | 0.04 |

| Optimism | 2.29 | 2.36 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 2.26 | 0.49 | 0.10 |

| Anxiety | 2.29 | 2.16 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 1.88 | 0.72 | 0.02 |

M pre, group mean at baseline; M post, group mean at end of treatment; M F/U, group mean at 2-month follow-up assessment. Because between-group comparisons include only those subjects available for follow-up analyses, n = 37 for M pre and M post; n = 25 for M F/U. d, p correspond to effect size for comparison to baseline score (M pre).

Table 2.

Changes in spiritual well-being and psychological functioning following supportive group therapy

| M Pre | M Post | d | p | M F/U | d | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual well-being | |||||||

| FACIT total | 2.07 | 2.15 | 0.13 | 0.58 | 2.28 | 0.19 | 0.50 |

| Meaning/Peace | 2.35 | 2.53 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 2.70 | 0.33 | 0.26 |

| Faith | 1.51 | 1.37 | −0.24 | 0.33 | 1.42 | −0.22 | 0.45 |

| Psychological functioning | |||||||

| Depression | 14.50 | 16.22 | −0.27 | 0.27 | 16.46 | −0.17 | 0.55 |

| Hopelessness | 8.28 | 7.72 | 0.11 | 0.64 | 8.08 | 0.15 | 0.60 |

| Desire for death | 4.33 | 4.50 | −0.04 | 0.19 | 4.00 | 0.10 | 0.71 |

| Optimism | 2.51 | 2.45 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 2.75 | 0.38 | 0.20 |

| Anxiety | 2.06 | 2.11 | −0.13 | 0.61 | 1.93 | 0.07 | 0.80 |

M pre, group mean at baseline; M post, group mean at end of treatment; M F/U, group mean at 2-month follow-up assessment. Because between-group comparisons include only those subjects available for follow-up analyses, n = 18 for M pre and M post; n = 13 for M F/U. d, p correspond to effect size for comparison to baseline score (M pre).

Effect sizes representing improvement in spiritual well-being were even larger at the 2-month follow-up assessment for the SWB total score, t(25) = 4.98, p<0.0001, the Meaning/Peace subscale, t(25) = 5.29, p<0.0001 and the Faith subscale, t(25) = 2.73, p = 0.006. Changes between baseline and 2-month follow-up assessment remained small and not statistically significant for SGP participants.

Repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated that significant group differences in improvement for SWB total score, F(2,74) = 5.05, p = 0.009 for the group x–time interaction, along with a significant main effect for time, F(2,74) = 8.30, p<0.001. Thus, while both groups showed some improvement in spiritual well-being, the increases were significantly greater for MCGP patients. Post hoc analyses demonstrated that the change in spiritual well-being from baseline to post-treatment differed significantly between groups, F(1,37) = 14.23, p<0.001, whereas there was no significant difference in changes between post-treatment and the 2-month follow-up assessment, F(1,37) = 1.41, p = 0.25.

A similar pattern of findings was observed for the Meaning/Peace subscale of the SWB, with a significant group x–time interaction, F(2,74) = 3.80, p = 0.03 along with a significant main effect for time, F(2,74) = 11.09, p<0.0001. Thus, while both groups showed some increase on the Meaning/Peace subscale, increases were significantly greater for MCGP patients. Post hoc analyses indicated that the largest group differences were between baseline and post-treatment, F(1,37) = 5.76, p = 0.02, with no group difference between post-treatment and follow-up, F(1,37) = 0.76, p = 0.86. The Faith subscale also showed a significant group x–time interaction, F(2, 74) = 4.24, p = 0.02, but no significant main effect for time, F(2, 74) = 1.28, p = 0.28, indicating that only patients participating in MCGP demonstrated improvement on the Faith subscale. Post hoc analyses indicated a significant group difference in change between pre-treatment and post-treatment, F(1, 37) = 2.83, p = 0.03, but not between post-treatment and follow-up, F(1, 37) = 2.33, p = 0.13.

Impact of treatment on psychological functioning

Analysis of changes in psychological functioning following MCGP participation revealed more modest treatment effects for measures of distress than was observed for spiritual well-being (see Table 1). Effect sizes for changes between pre- and post-treatment approached significance for three of the five distress variables: hopelessness, t(49) = 1.88, p = 0.07; desire for death, t(50) = 1.76; p = 0.09; and anxiety, t(36) = 1.74, p = 0.10. However, at the 2-month follow-up assessment effect sizes were larger and statistically significant for desire for death, t(25) = 2.09, p = 0.04 and anxiety, t(25) = 3.00, p = 0.02. There were no significant changes on any of the psychological functioning variables, either between pre- and post-treatment or between pre-treatment and 2-month follow-up for SGP participants (see Table 2).

Repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated no significant group differences in the magnitude of change between participants in the MCGP and SGP groups. However, differences in treatment effects approached significance for optimism (the LOT), F(2, 33) = 3.23, p = 0.06. In this analysis, the group differences in change in optimism occurred during the post-treatment phase (post-treatment to follow-up), F(1, 34) = 4.43, p = 0.05, with no significant difference in changes between pre- and post-treatment, F(1, 34) = 2.35, p = 0.13. This analysis suggests that improvement on the LOT was greater for MCGP patients than SGP patients, particularly during the 2-month follow-up period. There were neither significant differences in improvement nor any significant main effects for time (i.e. significant improvement regardless of treatment group), for measures of depression or anxiety. Likewise, there was no significant group difference in the Beck Hopelessness Scale or the schedule of attitudes towards hastened death, although there was a significant main effect for time for the latter variable, indicating reduced desire for death between both groups (see Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

Clinical interventions for patients approaching the end of life have the potential to dramatically improve quality of life in this final phase. Few interventions have been developed specifically for terminally ill patients and those who have been developed have rarely addressed spiritual well-being and meaning as primary outcomes. In response to this need, we developed Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy (MCGP) based on research demonstrating the importance of spiritual well-being and meaning, and the need for a brief intervention to address these issues in the terminally ill. This study demonstrated significantly greater benefits from MCGP compared with supportive group psychotherapy (SGP), particularly enhancing spiritual well-being and a sense of meaning. Treatment effects for MCGP appeared even stronger 2-month after treatment ended, suggesting that benefits not only persist, but may also grow after treatment has been completed. Patients who participated in SGP failed to demonstrate any such improvements, either at the post-treatment or at the 2-month follow-up assessment.

In addition to improved spiritual well-being and an enhanced sense of meaning, MCGP appears to reduce psychological distress, albeit to a lesser degree. We observed modest improvements in hopelessness, desire for death and anxiety, and these treatment effects increased over the 2-month follow-up period. Although differences between the two treatments were not observed for many of these variables using repeated measures ANOVA, this likely reflects the modest sample size, as effect sizes were substantial and in a consistent pattern across all measures. These effects may also have been attenuated by our study design, as participants were randomly assigned to treatment regardless of their level of distress (i.e. some participants had low levels of distress at baseline, and thus little room for improvement). Furthermore, prior research evaluating the impact of long-term group psychotherapy in the terminally ill also failed to significantly improve depression [15]. Hence, despite the strong association between depression and spiritual well-being, a meaning-focused intervention may not be the optimal method for treating depression for which other interventions (e.g. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) are stronger.

The failure of SGP to reduce psychological distress or improve spiritual well-being is also noteworthy. Previous research has demonstrated benefits from SGP [14,15], but rarely using short-term interventions or randomized designs with terminally ill patients. A more intensive supportive intervention may have generated greater improvements. Nevertheless, these findings raise questions as to whether short-term supportive psychotherapies provide measurable benefits for terminally ill cancer patients. It may be that interventions focusing on meaning and spiritual well-being are uniquely powerful for patients facing a terminal illness.

The high level of attrition raises concerns regarding feasibility and sample representativeness, and by extension, the interpretation of these results. Although high rates of attrition is common in research with terminally ill patients, the net result is a smaller sample of patients for analysis than would be ideal, precluding sophisticated statistical analyses or even a ‘correction’ for multiple outcome variables. Attrition also raises the possibility of sample bias. However, a large portion of attrition in this study occurred prior to randomization, reflecting the severity of illness in this sample rather than dissatisfaction with the assigned condition (which was unrelated to attrition, but reflected the slow pace of referrals to our study, in part because of limited outreach and limited funding). Clearly, this 8-week intervention designed for ambulatory, terminally ill cancer patients presents challenges with regard to consistent attendance (and even more so for a group-based intervention). Current research is addressing strategies to reduce attrition and improve attendance (e.g. by identifying terminally ill patients earlier in the disease trajectory). Future applications contrasting individual versus group formats for this intervention, determining the optimal number of sessions, or the optimal number of participants in each group may also help address issues of feasibility, optimal treatment delivery format and dissemination strategies. In addition, a larger sample would permit an analysis of treatment response differences across the groups or group leaders. Clearly, a modified version of this intervention may have applications for a variety of patient populations, including cancer survivors or those at an earlier stage of disease, or as a bereavement intervention for surviving family members. We are currently conducting a large, randomized trial to extend these preliminary findings and more thoroughly assess many of the issues raised by this pilot study (described above).

Despite these limitations, this pilot study provides preliminary support for the effectiveness of MCGP as a novel intervention for improving spiritual well-being, a sense of meaning, and psychological functioning in patients with advanced cancer. We observed large treatment effects after a short-term intervention and these benefits appear to increase even in the weeks after treatment ended. Although preliminary, MCGP may be an important step towards enhancing quality of life for patients at the end of life.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (R21 AT/CA0103, W. Breitbart, P.I.) and the Fetzer Institute (W. Breitbart, P.I.).

References

- 1.Breitbart W, Gibson C, Poppito S, Berg A. Psychotherapeutic interventions at the end of life: a focus on meaning and spirituality. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:366–372. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee V, Cohen SR, Edgar L, Laizner AM, Gagnon AJ. Meaning-making intervention during breast or colorectal cancer treatment improves self-esteem, optimism, and self-efficacy. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:3133–3145. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5520–5525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rousseau P. Spirituality and the dying patient. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2000–2002. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill cancer patients. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:2907–2911. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClain C, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. The influence of spirituality on end-of-life despair among terminally ill cancer patients. Lancet. 2003;361:1603–1607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson C, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Galietta M. Spirituality, depression and religion in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:213–220. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW. Group therapy in the cancer setting. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Koopmans J, et al. Randomized trial of group psychosocial support in metastatic breast cancer: the BEST (Breast-Expressive Supportive Therapy) study. Can Treat Rev. 1996;22:91–96. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(96)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiegel D, Stein SL, Earhart TZ, Diamond S. Group psychotherapy and the terminally ill. In: Chochinov H, Breitbart W, editors. The Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelman S, Bell DR, Kidman AD. A group cognitive therapy programme with metastatic breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:295–305. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199907/08)8:4<295::AID-PON386>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edmonds CVI, Lockwood GA, Cunningham AJ. Psychological response to long-term group therapy: a randomized trial with metastatic breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:74–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199901/02)8:1<74::AID-PON339>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiegel D, Yalom I. A support group for dying patients. Int J Group Psychoth. 1978;28:233–245. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1978.11491609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:527–533. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780300039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yalom ID, Greaves C. Group therapy with the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1977;134:396–400. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kissane DW, Bloch S, Smith GC, et al. Cognitive-existential group psychotherapy for women with primary breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12:532–546. doi: 10.1002/pon.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coward DD. Facilitation of self-transcendence in a breast cancer support group: II. Onc Nurs Forum. 2003;30:291–300. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenstein M, Breitbart W. Cancer and the experience of meaning: a group psychotherapy program for people with cancer. Am J Psychotherapy. 2000;54:486–500. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2000.54.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breitbart W. Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality and meaning-centered group psychotherapy intervention in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2000;10:272–278. doi: 10.1007/s005200100289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frankl VF. Man’s Search for Meaning. 4. Beacon Press; Massachusetts: 1959/1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frankl VF. The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy (expanded edn) Penguin Books; New York: 1969/1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D. A case of including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;8:417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the Beck Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Stein K, et al. Measuring desire for death among patients with HIV/AIDS: the schedule of attitudes toward hastened death. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:94–100. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: Macleod CM, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; New York: 1949. pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cain EN, Kohorn EI, Quinlan DM, et al. Psychosocial benefits of a cancer support group. Cancer. 1986;57:183–189. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860101)57:1<183::aid-cncr2820570135>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Payne DK, Lundberg JC, Brennan MF, Holland JC. A psychosocial intervention for patients with soft tissue sarcoma. Psyco-Oncology. 1997;6:65–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199703)6:1<65::AID-PON236>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]