Figure 2.

Bioinformatic and Experimental Validation of miRNA-mRNA Interactions

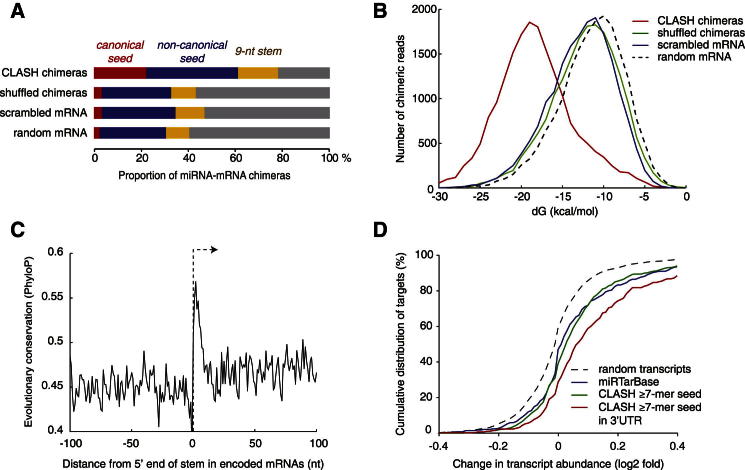

(A) Proportion of canonical seed interactions (exact Watson-Crick pairing of nts 2–7 or 3–8 of the miRNA), noncanonical seed interactions (pairing in positions 2–7 or 3–8, allowing G-U pairs and up to one bulged or mismatched nucleotide), or 9 nt stems (allowing bulged nucleotides in the target) among CLASH chimeras and several randomized data sets; the differences between CLASH and randomized data sets were highly significant (chi-square tests, p < 10−300, p < 10−100, and p < 10−80 for canonical seeds, noncanonical seeds, and stems, respectively).

(B) The mean predicted binding energy between miRNA and matching target mRNA found in chimeras was stronger by over 5 kcal mol−1 than in randomly matched pairs (t test, p < 10−300).

(C) Average conservation score along mRNA 3′ UTRs, centered at the 5′ end of the longest stem predicted within each CLASH target. The mean conservation score within predicted stems was significantly higher than in flanking regions of the 3′ UTR (0.54 versus 0.46, t test, p < 10−26, n = 4634).

(D) Changes in mRNA abundance following the depletion of 25 miRNAs (Hafner et al., 2010a). The graph shows a cumulative distribution of the log2 fold change (LFC) of mRNA abundance upon miRNA depletion for different sets of mRNAs: targets of the 25 miRNAs identified by CLASH with a 7-mer seed match (green line), CLASH targets in the 3′ UTR with 7-mer seed match (red line), targets extracted from the miRTarBase (blue line), and random transcripts with expression levels matching the CLASH targets (dashed line). Displacement of the curve to the right reveals increased abundance following miRNA depletion, which is indicative of mRNA repression in the presence of the tested miRNAs.