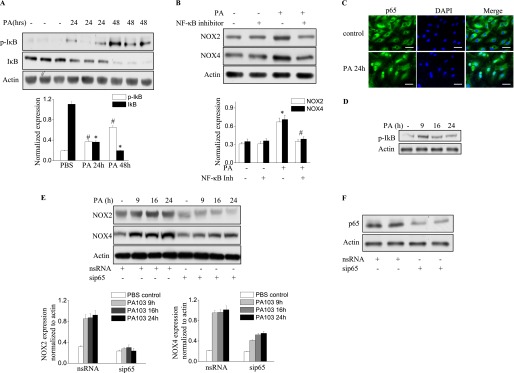

Figure 3.

P. aeruginosa induces NOX2 and NOX4 expression via the NF-κB pathway. (A) Lung tissue from mice exposed to PA103 was used for the immunoblot analysis of IκB and phosphorylated IκB. A significant phosphorylation of IκB (#P < 0.01, compared with PBS control samples) and degradation of IκB occurred in the lungs (*P < 0.01, compared with PBS control samples). (B) The inhibition of NF-κB activity in the lung by an intravenous injection of NF-κB inhibitor at a dose of 1 mg/kg before PA103 stimulation blocked NOX2 and NOX4 induction (*P < 0.05, compared with PBS control samples; #P < 0.05, compared with the PA103 treatment group). (C) Immunofluorescence staining of NF-κB subunit p65 was performed after P. aeruginosa treatment for 6 hours. Images were captured using a fluorescent microscope (×200), and the images shown are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bars, 30 μm. (D) The activation of NF-κB was verified by immunoblotting. HLMVECs were exposed to PA103 for the indicated times. The phosphorylation of IκB was analyzed by Western blotting. *P < 0.01, compared with vehicle control samples. (E) HLMVECs were transfected with scRNA or NF-κB subunit p65 small interfering (si)RNA (sip65) for 72 hours, followed by PA103 challenge for the indicated times. Western blotting was performed to detect NOX4 and NOX2 expression. *P < 0.01, compared with scRNA PA MOI = 10 (n = 3). #P < 0.01, compared with scRNA PA MOI = 10 at 9 hours, 16 hours, and 24 hours (n = 3). (F) The knockdown of p65 was confirmed by Western blotting.