Abstract

The birth canal provides mammals with a primary maternal inoculum, which develops into distinctive body site-specific microbial communities post-natally. We characterized the distal gut microbiota from birth to weaning in mice. One-day-old mice had colonic microbiota that resembled maternal vaginal communities, but at days 3 and 9 of age there was a substantial loss of intestinal bacterial diversity and dominance of Lactobacillus. By weaning (21 days), diverse intestinal bacteria had established, including strict anaerobes. Our results are consistent with vertical transmission of maternal microbiota and demonstrate a nonlinear ecological succession involving an early drop in bacterial diversity and shift in dominance from Streptococcus to Lactobacillus, followed by an increase in diversity of anaerobes, after the introduction of solid food. Mammalian newborns are born highly susceptible to colonization, and lactation may control microbiome assembly during early development.

Keywords: community structure, intestinal microbiota, mammal development

Introduction

Mammals are thought to develop in a bacteria-free environment within the mother's womb. They are born through a birth canal densely populated by lactic acid bacteria (Harrison et al., 1953; Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010; Ravel et al., 2011) and, during a substantial period of their early development, feed exclusively on maternal milk. These conserved traits may be important for the nutrition and protection of the newborn (Sela and Mills, 2010). In this work, we characterized the mouse intestinal microbiota from the early stages of development until weaning.

Materials and methods

Six Friend leukemia virus B (FVB) female mice, 4–5 weeks old, were bred with males, and the intestinal contents of litters and mothers were sampled until weaning (Supplementary Figure S1). This work was approved by the University of Puerto Rico IACUC (604-2008). Owing to the low fecal yield in newborn mice, colon contents were collected at these stages. We confirmed that colon contents were good proxies for feces (Supplementary Figures S2–S5), as reported (Peterson et al., 2008; Turnbaugh et al., 2009).

DNA was extracted from 81 samples using MoBio PowerSoil Kits (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer, including bead beating. Sample DNA was PCR-amplified from the variable V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene, then sequenced using 454 pyrosequencing (Life Sciences Genome Sequencer FLX instrument, Roche, Branford, CT, USA) as described (Andersson et al., 2008; Fierer et al., 2008), (Hamady et al., 2008). Sequences were processed using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) 1.4 (Caporaso et al., 2010). Rarefaction analysis was performed based on the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and the amount of phylogenetic branch length observed in each sample (Hamady et al., 2010). Good's coverage estimator was also calculated. Beta diversity was estimated using the UniFrac metric (Lozupone and Knight, 2005), and hierarchical clustering was performed using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA). Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were made using the statistical program R, version 2.14.0 (2011-10-31), using the R library.

Results

We obtained 121 893 V2 region 16S rRNA gene sequences from 81 samples, with a mean of 1505±274 sequences per sample. Sequences were clustered into 3822 OTUs. Unknown bacteria represented a total of 3.9% of the 121 893 sequences. The global estimated coverage was 98.8%, the coverage values for the offspring at each age were as follows: day 1=96.2% day 3=98.5% day 9=99.3% day 21=97.3% adults (older than 21 days)=96.9%.

Adult mothers harbored 61±21.7 fecal OTUs, with dominance of phyla Firmicutes (52.3%), Bacteriodetes (42.1%) and unclassified OTUs (4.8%) (Supplementary Figure S6; Supplementary Table S1). Bacterial communities of the adults did not vary significantly with age (Supplementary Figure S7), gender (Supplementary Figure S8) or physiological stage associated to parturition (ANOVA, P=0.124; Supplementary Figure S9).

At day 1 after delivery, the vaginas of the six mothers harbored ∼38±11.5 OTUs, with a dominance of Proteobacteria (80%) and Firmicutes (17%) (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table S2). Colonic bacterial communities in newborn mice at early ages were closer to maternal communities in vaginas than to those in feces (ANOVA, P=0.000), but by age 21 days, they clustered closer to maternal feces (ANOVA, P<0.001), as shown by Principal Coordinates Analysis (Supplementary Figure S10) and UPGMA clustering (Supplementary Figure S11).

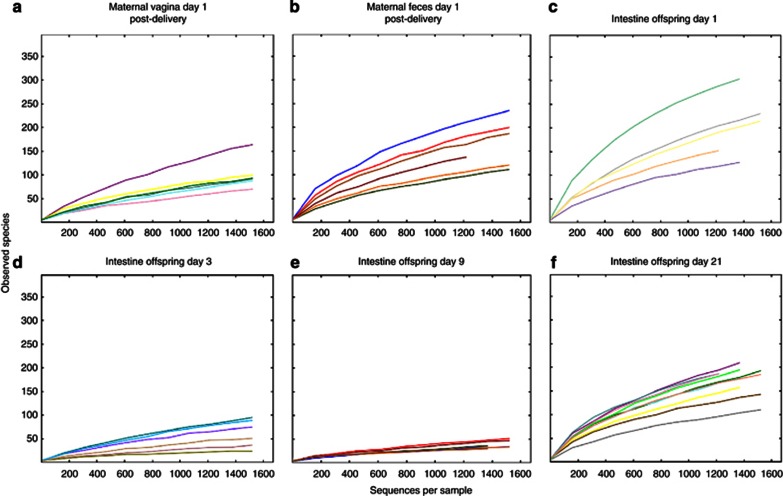

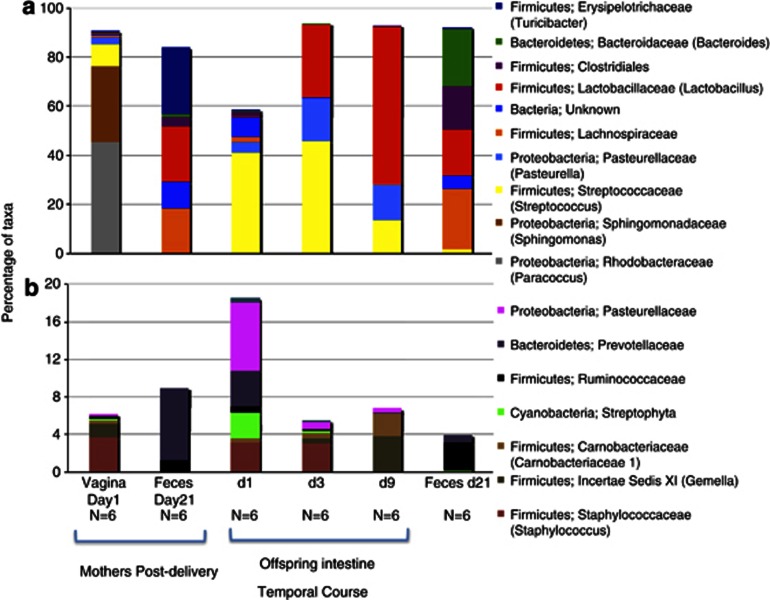

The colonic bacterial diversity decreased considerably at age 3 and 9 days (Figure 1, Supplementary Figures S12–S15, Supplementary Table S3), from nearly complete dominance of Streptococcus to Lactobacillus (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S16, Supplementary Table S2). By the time of weaning (21 days), the fecal diversity had increased to similar levels to those in the mothers (Figure 1, Supplementary Figures S13–S15, Supplementary Table S2), and with nearly complete disappearance of the Streptococcus species (Figure 2). Procrustes analysis shows that these results are robust to the sequence coverage obtained here (Supplementary Materials), and the decrease in diversity during the mid-strict lactation period is supported by other diversity metrics, including phylogenetic diversity (Supplementary Figure S13), Chao1 (Supplementary Figure S14) and Shannon entropy (Supplementary Figure S15).

Figure 1.

Rarefaction curves of observed species from mothers and offspring mice. (a) Maternal vagina, day 1 post delivery; (b), maternal feces, day 1 post delivery; (c), offspring intestine, day 1 of life; (d), offspring intestine, day 3 of life; (e), offspring intestine, day 9 of life; (f), offspring intestine, day 21 of life.

Figure 2.

Proportions of colonic bacterial families in maternal vagina and feces, and during offspring development. (a) dominating taxa. (b) low abundance taxa.

Discussion

Consistent with prior studies in humans (Matsumiya et al., 2002; Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010), bacterial communities in the colon of newborn mice resemble maternal vaginal communities. Site-specific selective factors exert pressure during development, and divergence of communities occurs in each body location. Previous work based on cultivable bacteria in mice (Schadler, 1973) has shown an initial colonization by Lactobacilli, followed by coliforms, and finally by obligate anaerobes. In the present study, there was an initial bacterial bloom of Streptococcus immediately after birth, which decreased after day 3 to be replaced by Lactobacillus species that are facultative anaerobes that ferment milk lactose and casein, and produce lactic acid (Kunji et al., 1996; Jiang and Savaiano, 1997; Angelakis et al., 2012). Lactate production acidifies (pH<5.5) the intestinal contents and inhibits the growth of anaerobes (Soergel, 1994; Jiang and Savaiano, 1997), including Lachnospiracea, Clostridiales and Bacteroidales, whose abundance was increased by the time of weaning. The introduction of solids to the milk diet increases the diversity of substrates for intestinal bacteria, and the strictly anaerobic colonizers become established with new pathways of fermentation, leading to the production of short-chain fatty acids, hydrogen, methane and CO2 (Ruppin et al., 1980). The importance of select groups of bacteria including SFB, Clostridium, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, in their role on the host mucosal immune system, has been recently reviewed (Reading and Kasper, 2011).

Contrary to the proposed developmental choreography with steady age-associated increase in microbiota alpha diversity (Koenig et al., 2011), the results presented here provide evidence of a biphasic progression toward the adult colonic microbiota, with an early reduction of diversity during suckling with dominance by lactate producers, and a second phase with increased diversity by anaerobes, coinciding with the introduction of solid food.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge undergraduate students Angela Alicea and Diego Borralí Falcón, technicians from the animal facility Luis Rosario and Andrés Rodríguez, for their valuable help and the UPR Sequencing and Genotyping facility, supported by NCRR AABRE grant #P20 RR16470, NIH-SCORE grant #S06GM08102 and NSF-CREST grant #0206200, NINDS-SNRP U54 NS39405 This work was supported by Puerto Rico Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (PR-LSAMP), RISE grant 5R25GM061151, NSF grant HRD0206200, Diane Belfer Program in Human Microbial Ecology, the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Backhed F, Nyren P, Engstrand L. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis E, Armougom F, Million M, Raoult D. The relationship between gut microbiota and weight gain in humans. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:91–109. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, Hamady M, Lauber CL, Knight R. The influence of sex, handedness, and washing on the diversity of hand surface bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17994–17999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807920105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamady M, Lozupone C, Knight R. Fast UniFrac: facilitating high-throughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequencing and PhyloChip data. ISME J. 2010;4:17–27. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamady M, Walker JJ, Harris JK, Gold NJ, Knight R. Error-correcting barcoded primers for pyrosequencing hundreds of samples in multiplex. Nat Methods. 2008;5:235–237. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison W, Jr., Stahl RC, Magavran J, Sanders M, Norris RF, Gyorgy P. The incidence of Lactobacillus bifidus in vaginal secretions of pregnant and non-pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1953;65:352–357. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(53)90438-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Savaiano DA. In vitro lactose fermentation by human colonic bacteria is modified by Lactobacillus acidophilus supplementation. J Nutr. 1997;127:1489–1495. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.8.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 (Suppl 1:4578–4585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunji ER, Mierau I, Hagting A, Poolman B, Konings WN. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:187–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00395933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumiya Y, Kato N, Watanabe K, Kato H. Molecular epidemiological study of vertical transmission of vaginal Lactobacillus species from mothers to newborn infants in Japanese, by arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Chemother. 2002;8:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s101560200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson DA, Frank DN, Pace NR, Gordon JI. Metagenomic approaches for defining the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 (Suppl 1:4680–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading NC, Kasper DL. The starting lineup: key microbial players in intestinal immunity and homeostasis. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:148. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppin H, Bar-Meir S, Soergel KH, Wood CM, Schmitt MG., Jr Absorption of short-chain fatty acids by the colon. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:1500–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadler R. The relationship between the host and its intestinal microflora. Proc Nutr Soc. 1973;32:41–47. doi: 10.1079/pns19730013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela DA, Mills DA. Nursing our microbiota: molecular linkages between bifidobacteria and milk oligosaccharides. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soergel KH. Colonic fermentation: metabolic and clinical implications. Clin Investig. 1994;72:742–748. doi: 10.1007/BF00180540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Knight R, Gordon JI. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:6ra14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.