Abstract

Allele-specific methylation (ASM) has long been studied but mainly documented in the context of genomic imprinting and X chromosome inactivation. Taking advantage of the next-generation sequencing technology, we conduct a high-throughput sequencing experiment with four prostate cell lines to survey the whole genome and identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with ASM. A Bayesian approach is proposed to model the counts of short reads for each SNP conditional on its genotypes of multiple subjects, leading to a posterior probability of ASM. We flag SNPs with high posterior probabilities of ASM by accounting for multiple comparisons based on posterior false discovery rates. Applying the Bayesian approach to the in-house prostate cell line data, we identify 269 SNPs as candidates of ASM. A simulation study is carried out to demonstrate the quantitative performance of the proposed approach.

Keywords: DNA Methylation, ASM, Next-generation Sequencing, SNP

1 Introduction

DNA methylation is the most common epigenetic mechanism that plays a key role in transcription regulation [1], and it has been linked with many complex diseases [2, 3]. Since DNA methylation is reversible, it is a promising target for therapeutic interventions. Allele specific DNA methylation (ASM) is a form of allelic asymmetries where methylation occurs on one specific allele but not on the alternative allele. Locating genomic regions with ASM has been traditionally studied in the field of genome imprinting [4]. If a gene is imprinted, the inactive allele will be significantly more methylated than the actively expressed allele, which is also associated with allele specific expression. Another major type of ASM is X chromosome inactivation for females, where DNA methylation coordinates the random silencing of the X chromosome. X chromosome inactivation in any cell is maintained once established so that the inactivated allele is transcriptionally silenced. To date, only a handful of ASM regions have been identified [5].

The recent development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has the potential to greatly improve the ability to detect and understand ASM [6] since NGS applications are able to achieve high resolution at the level of single nucleotide. Methylation typically occurs at the C5 position of cytosines within CpG sites (a cytosine next to a guanine). Bisulfite sequencing, a DNA sequencing method in combination with bisulfite conversion, is the current gold standard for methylation analysis, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines intact. If bisulfite-based sequencing data are available, investigators can precisely determine the methylation state of each CpG site on the two alleles. Standard statistical tests such as the Fisher’s exact test can then be used to compare the proportion of methylated CpG sites on the two alleles and test the hypothesis whether methylation is significantly associated with one specific allele [7]. However, bisulfite sequencing is costly and most studies using bisulfite sequencing to detect ASM have been restricted to targeted genomic regions. For example, Zhang et al. (2009) [8] analyzed chromosome 21, the shortest autosome in human, and only identified four distinct amplicons with ASM.

Due to the high cost and limitations of bisulfite sequencing, enrichment-based NGS technologies have been developed for whole-genome DNA methylation studies [9, 10], which are more affordable in a general laboratory setting. Popular enrichment-based NGS methods include MeDIP-seq [11] and MBD-seq [12]. A comprehensive comparison of these two sequencing methods and the bisulfite sequencing methods in profiling DNA methylation can be found in Harris et al. (2010) [13]. Unlike the bisulfite-based methods, enrichment-based sequencing methods typically only allow for binary calls of methylation. For general NGS data obtained from enrichment-based methods without bisulfite conversion, there is a lack of formal statistical tools for detecting ASM. In this paper, we propose a novel Bayesian approach to screen single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with ASM by incorporating SNP genotyping information with the sequencing data. Our approach separately models the data from biological samples with different genotypes. For each SNP, a Poisson-Binomial model or a Negative-Binomial-Binomial model with genotype-dependent parameters is applied to the short reads overlapping that SNP locus, leading to a posterior probability of methylation. The overall posterior probability of ASM for that SNP is obtained by combining the methylation probabilities across different genotypes. Source R code is available at http://stat.cwru.edu/~bxh123.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we first introduce the motivating prostate cell line study. Then we define ASM as a probability event and propose the Bayesian approach for posterior inference. In particular, we introduce two hierarchical models, Poisson-Binomial and Negative-Binomial-Binomial, to model the short-read counts. We also describe how to screen SNPs with ASM by controlling for Bayesian false discovery rates. In Section 3, the proposed Bayesian approach is applied to the prostate cell line study, and statistical inference of ASM is conducted based on the in-house MBD-Seq data. A simulation study is also carried out to demonstrate the quantitative performance of our method. Conclusions and discussions are provided in Section 4.

2 Methods

2.1 A Prostate Cell Line Study

We investigated ASM based on DNA-seq data obtained from four prostate cell lines, including PrEC, RWPE, LNCaP, and Du145. These cell lines were processed using the methyl-CpG binding domain protein sequencing (MBD-seq) method, which produced about 14 millions short DNA reads. These short reads were mapped to the human genome Hg18 (NCBI Build 36.1, UCSC) using the BOWTIE algorithm [14].

For SNP calling, each cell line was processed twice on an Illumina array (Illumina Genome-wide DNA analysis BeadChip Human660w-QUAD). SNPs with inconsistent calls between these replicates were removed from further analysis. We also excluded SNPs with a single homozygous genotype in all four cell lines since only one allele was represented for these SNPs. Moreover, the method proposed by Wang et al. (2007) [15] was applied to identify genomic regions with copy number variation (CNV). To limit false discovery due to CNV, SNPs that lie in the regions identified with CNV were also excluded. After these, we surveyed a total of 56,440 SNPs and retrieved the number of uniquely mapped short reads overlapping with each SNP. The SNP coordinates were obtained from the UCSC Hg18 assembly.

In a NGS methylation study, the count of short reads mapped to a genomic region typically represents the strength of the underlying methylation signal. In general, a zero count means no methylation for that region. Among the 56,440 SNPs, 44,594 had no reads mapped in all four cell lines. This left a total of 11,846 SNPs for ASM analysis. On the other hand, a genomic region can be considered as being methylated if the tag count is large. However, there is no established threshold of the read count for calling methylation in the literature. Laurent et al. (2010) [16] assumes that three mapped reads would be sufficient for calling methylation while others prefer larger thresholds [17]. When a SNP exhibits ASM, the number of reads mapped to its two alleles should differ greatly. Generally speaking, there should be a large number of reads mapped to one allele but few reads mapped to the alternative allele. Therefore an accurate quantification of the number of reads mapped to two alleles is crucial for ASM analysis.

Degner et al. [18] found that there could be a bias towards higher mapping rate of the allele in the reference genome, which was referred to as allele-specific mapping bias (ASMB). To correct such a bias, we applied the procedures proposed in [18] to the data in our prostate cell line study. With the ASMB-correction procedures, 11,693 SNPs were found to have reads mapped in at least one cell lines and were included in further ASM analysis, of which 11,654 (99.7%) were also found when not using the correction procedures. For our prostate study, applying ASMB-correction results in minor changes. In general, we recommend ASMB-correction as a necessary pre-processing step. More details about the MBD sequencing procedure, read mapping and data pre-processing are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

2.2 Definition of ASM

Suppose that a SNP carries alleles A and B. Then three different genotypes could be observed at this SNP locus, including AA, BB and AB. If this SNP exhibits ASM, either allele A or allele B is methylated while the alternative allele is not. Such a methylation asymmetry of the two alleles would imply two consistent patterns across the three possible genotypes. More specifically, in the case of A-allele specific methylation, this SNP will be methylated in samples with genotypes AA and AB but not methylated in sample with genotype BB. Similarly, this SNP will be only methylated in samples with genotypes BB and AB in the case of B-allele specific methylation.

To define ASM as a probability event, we introduce a set of latent variables sg that represent all possible methylation states (allele-specific or not) of the SNP in samples with genotype g, with g taking a value in {0,1,2}, corresponding to “AA”, “AB” or “BB”, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the values of sg and the corresponding methylation states. For the homozygous genotypes (AA and BB), we only need to consider two methylation states

=

=

= {0, 1}, in which 0 for no methylation and 1 for methylation, since the SNP only carries one particular allele at the SNP locus. For the heterozygous genotype (AB), methylation may occur on neither, one, or both alleles. Therefore we should consider four methylation states

= {0, 1}, in which 0 for no methylation and 1 for methylation, since the SNP only carries one particular allele at the SNP locus. For the heterozygous genotype (AB), methylation may occur on neither, one, or both alleles. Therefore we should consider four methylation states

= {0, 1, 2, 3}, indicating no methylation, methylation on allele A only, methylation on allele B only and methylation on both alleles, respectively.

= {0, 1, 2, 3}, indicating no methylation, methylation on allele A only, methylation on allele B only and methylation on both alleles, respectively.

Table 1.

Definition of the latent variable sg by genotypes

| Methyl. State | Genotype

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| AA (g = 0) | AB (g = 1) | BB (g = 2) | |

| s0 | s1 | s2 | |

| No Methyl. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A Methyl. B Not | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| B Methyl. A Not | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| A and B both Methyl. | 1 | 3 | 1 |

By the definition of sg, the event of A-allele specific methylation (A-ASM) is equivalent to the cross-genotype event,

Similarly, the event of B-allele specific methylation (B-ASM) corresponds to the event {s0 = 0, s1 = 2 and s2 = 1}. Therefore inference on ASM can be made by estimating the latent triplets (s0, s1, s2) when multiple samples of different genotypes are available. It is worth emphasizing that the definition of ASM in this paper is restricted to the cases where one allele is methylated but the alternative allele is not. A broader definition of ASM could include the cases where both alleles are methylated at different levels. However, this requires a precise quantification of methylation level as a continuous variable instead of a binary call of methylation for the two alleles, which can only be achieved using the bisulfite-based sequencing technologies up to date. In the following section, we describe a Bayesian approach that computes the posterior probabilities of A- and B-ASM given the sequencing and genotyping data.

2.3 A Bayesian Approach

Suppose that sequencing data are obtained for m samples. For our data m = 4 representing the four cell lines. For sample j, j = 1, · · ·, m, let Gj be the genotype of the SNP, nj be the total number of short reads overlapping with the SNP locus, and aj and bj be the numbers of short reads on the A allele and the B allele, respectively. Since a short read will be mapped to either allele A or allele B, we should observe nj = aj +bj in general. However, due to a variety of reasons such as sequencing error [19] and the existence of multiple alleles [20], the sum aj + bj could be smaller than nj. In these rare cases, we may restrict the analysis to the reads mapped to the two alleles only and set nj = aj + bj.

Modeling the read counts requires specifying a joint distribution for the pair (nj, aj). Since aj is the number of reads mapped to allele A among all nj reads, it is natural to assume a Binomial distribution for aj given nj. The remaining piece is to model the marginal count nj. In the literature, Poisson and Negative Binomial distributions are the two common distributions for modeling read counts in NGS data [21]. We first discuss our approach in the context of a Poisson distribution for nj. More specifically, conditional on the observed genotype Gj = g and the underlying methylation state sg = s, the joint distribution of the count pair (nj, aj) is given as

| (1) |

where λgs ≥ 0 is the rate parameter of the Poisson distribution and αgs ∈ [0, 1] is the percentage parameter of the Binomial distribution. The likelihood function for a single sample is given by

where I(·) is the indicator function, and qgs = P (sg = s) represents the probability that the methylation state sg is s. With m independent samples, the overall likelihood function is then given by

| (2) |

Denote , ag = Σj:Gj=g aj and ng = Σj:Gj=g nj for a fixed g, the joint distribution of the read counts a = (a0, a1, a2), n = (n0, n1, n2) and the methylation states S = (s0, s1, s2) can be re-written as

| (3) |

with .

The goal is the posterior probability Pgs = P (sg = s|ng, ag). A full Bayesian implementation requires elicitation and calibration of prior distributions for the model parameters, including qgs, αgs and λgs. Computation cost will increase due to the need of Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations. Since our goal is to perform a fast and preliminary screen for ASM, we delay investigation of the full Bayesian approach for future research. Considering the large data size from NGS and the informative nature of the methylation biology, we decide to simplify the computation by eliciting the values of most parameters based on biological reasoning. Firstly, we assume a Dirichlet prior distribution for the probability vector q̄g = (qgs; s ∈

)T, that is,

with B(dg) = Πs Γ(dgs)/Γ(Σs∈

)T, that is,

with B(dg) = Πs Γ(dgs)/Γ(Σs∈

dgs). The Dirichlet parameters dg = (dgs, s ∈

dgs). The Dirichlet parameters dg = (dgs, s ∈

)T could be chosen to yield a small effect size by imposing the contraint Σs dgs = ε for ε ∈ (0, 1) [22]. For example, we set equal dgs with Σs∈

)T could be chosen to yield a small effect size by imposing the contraint Σs dgs = ε for ε ∈ (0, 1) [22]. For example, we set equal dgs with Σs∈

dgs = 0.5 in our numerical analyses. Similar numerical results (not shown) were obtained by randomly generating dgs in the simulations.

dgs = 0.5 in our numerical analyses. Similar numerical results (not shown) were obtained by randomly generating dgs in the simulations.

Secondly, we specify the value of αgs as given in Table 2, categorized by genotypes and methylation states. The justification of these values is summarized as follows. When ASM occurs at a SNP, the methylated allele will dominate in the sense that a high percentage of short reads will be mapped to the methylated allele. Since αgs reflects the proportion of the short reads mapped to the A allele, we set αgs at 0.9 when either the genotype is AA (i.e., there is no allele B) or only the A allele is methylated. In contrast, αgs takes a small value of 0.1 when either the genotype is BB or only allele B is methylated. When the genotype is AB and there is no methylation, we assume a uniform distribution U[0, 1] for α10. When the genotype is AB and both alleles are methylated, we set α13 = 0.5. A sensitivity analysis is later carried out to examine the specification of αgs on screening SNPs with ASM.

Table 2.

Values of αgs in the Poisson-Binomial and NB-Binomial models by genotypes and methylation states

| Genotype | Methylation state | |

|---|---|---|

| AA (g = 0) | No Methyl. (s0 = 0) | α00 = 0.9 |

| Methyl. (s0 = 1) | α01 = 0.9 | |

| BB (g = 2) | No Methyl. (s2 = 0) | α20 = 0.1 |

| Methyl. (s2 = 1) | α20 = 0.1 | |

| AB (g = 1) | No Methyl. (s1 = 0) | α10 ~ U (0, 1) |

| A Methyl. (s1 = 1) | α11 = 0.9 | |

| B Methyl. (s1 = 2) | α12 = 0.1 | |

| A and B Methyl. (s1 = 3) | α13 = 0.5 |

Finally, to determine the rate parameter λgs that characterizes the strength of the methylation signal when the methylation state is s, we suggest an empirical approach based on the observed data. Recall that the state indicator s = 0 implies that the SNP is not methylated, and a positive value of s implies methylation. Thus λg0 represents the mean read count when the SNP in the samples showing genotype g is not methylated. Its value should be small since if the SNP is not methylated, few reads will be mapped to its genomic location. In contrast, when s is positive, the SNP is methylated and λgs should be large. In summary, the mean read count could be assumed to follow a mixture of two distributions, one centered at a small value around 0 and the other at a large positive value. Therefore we fit a two-component mixture Poisson model to the read counts by pooling nj for all SNPs considered in the study. The density of the mixture Poisson model can be written as

| (4) |

where p is the mixing weight; λN is the mean count for the unmethylated SNPs and λM > λN is the mean count for the methylated SNPs. In other words, we assume that nj follows a Poisson distribution with mean λN if the SNP is not methylated, and follows a Poisson distribution with mean λM when it is methylated. Fitting the mixture Poisson models has been implemented in most standard packages. In this paper, we used the R package FlexMix [23]. After obtaining the maximum likelihood estimates for λN and λM in (4), we set λg0 = λ̂N and λgs = λ̂M for any s > 0. Here we apply the two-component mixture Poisson model to make binary calls of methylation based on the count data, which is widely used for general enrichment-based NGS data [13]. For bisulfite-based NGS data where the read counts accurately represent the underlying methylation level, another strategy could be to assume three Poisson distributions for the data, where the smallest λ denotes the mean read count for no methylation, the highest for two-allele methylation, and the middle value for one-allele methylation. These λ parameters can be then estimated by fitting a three-component mixture Poisson model.

Given these prior specifications, a closed form of the posterior probability Pgs = P (sg = s|ng, ag) exists as

| (5) |

The derivation of (5) are provided in the Supplementary Materials. The values of λgs are as discussed above. αgs should be substituted, according to the values in Table 2. The calculation of P10 in (5) integrates out α10 over its uniform prior distribution U(0, 1), leading to

where B(·, ·) is the Beta function. By the definition of A- and B-ASM, the triplets (P01, P11, P20) and (P00, P12, P21) are the posterior probabilities of interests.

Negative Binomial distribution is a popular alternative to the Poisson distribution for modeling NGS count data. The Negative Binomial distribution was proved to fit better to chip-sequencing (chip-seq) data, especially when there is over-dispersion in the count data [24]. Regarding DNA-seq methylation data, Yang et al. [21] showed that the Negative-Binomial distribution yielded more conservative results. Under the probability framework of our Bayesian approach, we can replace the Poisson density in (1) with a Negative-Binomial density, leading to

| (6) |

where ; μgs and φgs > 0 are the mean and dispersion parameters of the Negative-Binomial distribution, respectively. The variance of the Negative-Binomial distribution is . This model is called a Negative Binomial-Binomial (NB-Binomial) model throughout this paper.

Following the derivation of (5), the posterior probability Pgs for the NB-Binomial model is

| (7) |

where the product Πj:Gj=g P(aj, nj |sg = t) is proportional to

Similar to the mixture Poisson model (4), μgs and φgs in (7) can be determined by fitting a two-component mixture Negative-Binomial model to the pooled counts nj’s, where the density f (nj) is

| (8) |

with and , where p is the mixing weight; μM represent the mean read counts for the unmethylated and methylated SNPs, respectively; φN and φM are the two dispersion parameters. Since an unmethylated SNP should have a zero count in theory, one may assume a small μN and a large φN in fitting the mixture model (8). The posterior probability Pgs in (7) is then calculated by substituting the estimates for the corresponding parameters.

2.4 Probability of ASM and False Discovery Rate Control

The probability Pgs in (5) or (7) assesses the likelihood of the occurrence of the methylation state sg = s for genotype g. Since A-allele specific methylation is represented by (s0 = 1, s1 = 1, s2 = 0), statistical inference for A-ASM should be based on (P01, P11, P20). Similarly, the triplets (P00, P12, P12) shall be inspected for the B-allele specific methylation.

Combining probabilities across the three genotypes is analogous to multi-dimension decision making [25]. Each genotype can be considered as a dimension in our setting. Since the probability Pgs is obtained from samples with genotype g and samples with different genotypes are independent of each other, the posterior probabilities of A-ASM and B-ASM are, respectively,

| (9) |

Combining the three probabilities multiplicatively is conservative in the sense that PA and PB become small as long as the data from one genotype show evidence against ASM. If data are missing for one or two genotypes, that is, mg = 0 for some g, the calculation of PA and PB shall be based on the probabilities of the representing genotypes.

Since the event of ASM could be either the A-allele or the B-allele specific methylation and these two events are mutually exclusive, the overall probability of ASM is

| (10) |

For SNP i, i = 1, · · ·, n, let Pi denote the probability of ASM. When screening a large number of SNPs, we need to determine an appropriate cut-off value for selecting significant SNPs with ASM, we adopt the method proposed by Newton et al. (2004) [26], which is a Bayesian analogy of FDR [27] that minimizes the false non-discovery rate subject to maintaining a fixed FDR.

For a targeted FDR of ρ, we compute the expected number of false discoveries as for any given cut-off of k. The optimal cut-off kρ is the largest value among all k such that the observed FDR is smaller than ρ, that is,

| (11) |

After determining the value of kρ in (11), we may select those SNPs with I(Pi ≥ kρ) = 1 as candidate ASM sites for further biological study. This Bayesian FDR control method has been shown to be optimal by Müller et al. (2004) [28] and Müller et al. (2007) [29] in the sense that kρ in (11) and the associated decision rule of I(Pi ≥ kρ) = 1 minimizes the false negative rate among all decisions with FDR less than ρ.

3 Numerical Results

3.1 Application to the Prostate Cell Line Study

A total of 11,693 SNPs were analyzed using the Bayesian screening approach described in Sections 2.2 and 2.3. Among them, 11,105 (95%) SNPs have heterozygous genotypes represented, and 3,513 (30%) have all three possible genotypes represented in these cell lines. For the SNPs with heterozygous genotypes, Figure 1 shows a series a box plots of the average read count per cell line stratified by the proportions of the reads mapped to the A alleles. It appears that those SNPs with large read counts and percentages either higher than 80% or less than 20% are potential candidates with ASM since a large count means methylation and a proportion close to one or zero indicates that methylation is associated with one specific allele.

Figure 1.

Box plots of the average number of short reads per cell line stratified by the proportions of reads on the A alleles for the 11,105 SNPs with heterozygous genotypes

We first applied the Poisson-Binomial model to the data. The probabilities of ASM in (10) were shown in Figure 2a. At a Bayesian FDR of 0.05, a total of 269 (2.3%) SNPs were selected as candidates with ASM. Note that without the ASMB correction procedure, the Poisson-Binomial model selected a total of 272 SNPs (96% overlap). The behavior of the Bayesian FDR procedure was shown in Figure 2b. For the selected SNPs, the percentages of the short reads on the methylated alleles are at least 75% (Figure 3). The average read counts per cell line show a negative correlation with the percentages of the reads on the methylated alleles. If more than 90% of the short reads are mapped to the methylated allele, a median of 4 short reads per sample is required for calling ASM. The median count of short reads per sample increases to about 7 if the percentage lies in [80%, 90%], and to about 10 if the percentage is even lower than 80%.

Figure 2.

(a) Fitted probabilities of ASM for all SNPs using the Poisson-Binomial model (b) Bayesian FDR performance

Figure 3.

Read counts and percentages of the reads on the methylated alleles for the selected SNPs using Poisson-Binomial model

The histogram in Figure 4a shows the distribution of the pooled counts of short reads mapped to all SNPs, where 53% of the counts are zero. For all the positive counts, the mean is 3.3, and the variance is 30.9. The much larger variance indicates that there might be over-dispersion in the data. We then applied the NB-Binomial model to the data. At a Bayesian FDR of 0.05, a total of 257 SNPs were detected, and 235 (91%) of them also appear in the set of SNPs identified using the Poisson-Binomial model. 22 SNPs were only detected by the NB-Binomial model while 34 SNPs were only detected by the Poisson-Binomial model. Figure 4b compares the estimated probabilities of ASM from the Poisson-Binomial and NB-Binomial models for the SNPs selected by either or both models. The majority of the probabilities from the two models are highly correlated, with the NB-Binomial model yielding slightly less calls of ASMs than the Poisson-Binomial model.

Figure 4.

(a) Histogram of total read counts (njs) mapped to all SNPs from 4 cell lines; (b) Fitted probabilities of ASM for SNPs selected using Poisson-Binomial and NB-Binomial model

Figure 5 illustrates the sequencing and genotyping data of two SNPs selected by both models. For SNP rs3765696 located on chromosome 1, the genotype is heterozygous (CT) in the PrEC cell line and is homozygous (TT) in other three cell lines. In the PrEC cell line, 10 short reads overlap with this SNP, of which 9 (90%) are on the C allele and only 1 (10%) is on the T allele. This suggests that allele C is more prone to methylation than allele T. The data in other three cell lines are consistent, where only 2 reads are mapped at the SNP locus. The SNP rs2236998 is on chromosome 4 and is represented by all three genotypes in the four cell lines. In the PrEC cell line (genotype AG), 8 (80%) reads are on the G allele and 2 (20%) are on the A allele at the SNP locus, indicating G-allele specific methylation. In the LNCaP cell line with genotype GG, 7 reads are all on the G allele. In the RWPE and Du145 cell lines with genotype AA, only 1 read is mapped. Thus the data are consistent across these cell lines with the final call of G-ASM based on posterior inference. We examined more SNPs and found similar patterns, suggesting a reasonable fit of our proposed model.

Figure 5.

MBD sequencing and genotyping data of two selected SNPs, rs3765696 and rs2236998. (PrEC, RWPE, NCaP, DU145) are the four prostate cell lines in our MBD-Seq experiment

3.2 A Simulation Study

In this simulation study we considered 10,000 SNPs, each replicated in 4 samples. The first stage of the simulation was to simulate the genotypes across multiple samples and the true methylation pattern across the three possible genotypes for each SNP. Due to the small sample size of 4, some SNPs may not have all three genotypes represented as in the prostate cell line study. Therefore, for genotype AA, we considered three cases: (1) genotype missing; (2) allele A methylated and (3) allele A not methylated. Similarly, we considered three cases for genotype BB and five cases for genotype AB. The total number of cross-genotype methylation pattern is then 3 × 3 × 5 = 45. The proportion corresponding to each pattern was determined to approximate the prostate cell line data, and only 28 patterns were given positive proportions (see Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials). For each SNP, its methylation pattern across different genotypes was then randomly chosen from the list of 28 patterns according to the listed proportions.

Given a simulated methylation pattern, the second stage was to simulate the read counts. The total number of short reads overlapping with each SNP was generated from a Poisson or a Negative Binomial distribution, where the distribution parameters depend on the simulated genotype and methylation state. In the case of Poisson distribution, the total read count was generated from Poisson(0.5) regardless of the genotypes if a sample was assumed a non-methylation state. Otherwise, the total read count was generated from Poisson(λM ). We varied the value of λM from 3 to 9 to examine the quantitative performance of our approach in calling ASM. Given the total read count, a Binomial distribution with a percentage parameter 0.9 was assumed to generate the count of reads on the corresponding allele when the genotype is homozygous. For a heterozygous genotype, the binomial percentage parameter was 0.5, 0.9, 0.1 and 0.5, respectively, for the four methylation states considered in Table 1.

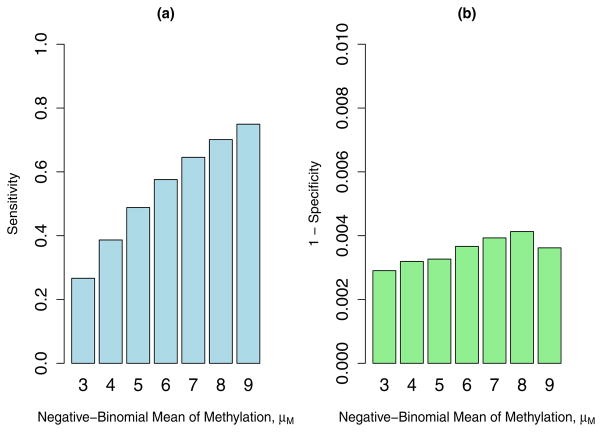

In the simulation study, the sensitivity and specificity of calling ASM were calculated at the Bayesian FDR of 0.05. We simulated the data 200 times for each λM. As the results, the sensitivity (average across 200 simulations) gradually increases with λM, the Poisson rate of the total read count for methylated samples (Figure 6a). The sensitivity is only 0.32 when λM is 3, and it becomes greater than 0.8 when λM is at least 7, which suggests that a read count of 7 is required to satisfactorily separate methylated SNPs from unmethylated ones. Meanwhile the specificity is very close to one in all simulation scenarios (Figure 6b), which confirms that combining probabilities across different genotypes multiplicatively is conservative in the sense that it reduces the false discovery rate. Table 3 summarizes the false positive and false negative rates in the simulations. The false positive rates are all smaller than the nominal level of 0.05 as expected, while the false negative rates decrease with the value of λM.

Figure 6.

Simulation results (Poisson-Binomial model): (a) Sensitivity of calling ASM with respect to λM; (b) Specificity of calling ASM with respect to λM

Table 3.

False positive and false negative rates (means (standard deviations)) of calling ASM with respect to λM (Poisson-Binomial model) in the simulations

| λM | False positive rate | False negative rate |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.041 (0.008) | 0.111 (0.002) |

| 4 | 0.040 (0.006) | 0.079 (0.002) |

| 5 | 0.036 (0.005) | 0.050 (0.002) |

| 6 | 0.031 (0.004) | 0.031 (0.002) |

| 7 | 0.029 (0.004) | 0.018 (0.002) |

| 8 | 0.035 (0.004) | 0.011 (0.001) |

| 9 | 0.033 (0.004) | 0.006 (0.001) |

In the data-generation process, the Binomial percentage parameter αgs was consistent with the suggested values in Table 2. To examine the effect of possible misspecification of the operating parameter αgs on SNP screening, a further sensitivity analysis was performed. Recall that the value of αgs was set at 0.9 to reflect the proportion of short reads on the methylated allele when ASM occurs. In the sensitivity analysis, we varied this value from 0.70 to 0.95. High sensitivity of calling ASM is achieved when αgs = 0.8, 0.85 and 0.90 (Figure 7a). The specificity is very close to one in all scenarios, with best results at 0.95 and slightly unsatisfactory results at 0.75, 0.80 and 0.85. In summary, we recommend a value of 0.9 for αgs.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity (a) and specificity (b) of calling ASM with respect to the operating parameter αgs in the Poisson-Binomial model

To examine the NB-Binomial model, the total read count was generated from NB(0.5, 100) regardless of the genotype if a sample had a non-methylation state. For the methylated samples, the total read count was generated from NB(μM, 3). Similar to the case of Poisson distribution, we examined the model performance by varying the value of μM from 3 to 9. The dispersion parameter was fixed at 3 so that the variance of the read count for the methylated SNPs ranged from 6 to 30. The sensitivity ranges from 0.25 to 0.82 (Figure 8a) as μM goes from 3 to 9, while the specificity is still close to one in all scenarios (Figure 8b). The sensitivity of detecting ASM is generally lower than the case of Poisson distribution, which suggests a higher coverage is needed for ASM detection when the count data present over-dispersion.

Figure 8.

Simulation results (NB-Binomial model): (a) Sensitivity of calling ASM with respect to μM; (b) Specificity of calling ASM with respect to μM

4 Discussion

We have proposed a Bayesian approach for screening SNPs with allele specific methylation based on enrichment-based NGS data and genotyping information from multiple samples. Probabilities of methylation are first derived for each genotype, and the overall probability of ASM is then derived by combining the probabilities of methylation across three possible genotypes multiplicatively. Our screening approach is based on a class of hierarchical models for the numbers of reads mapped to each SNP and its two alleles. A Poisson or Negative Binomial model is used to model the total read counts for a binary call of methylation, and a Binomial model is used to determine whether methylation is associated with one specific allele. We applied our approach to the data from a prostate cell line study, leading to 269 SNPs as candidates of ASM. The quantitative performance of the proposed models was also examined in a simulation study. If the count data can be well approximated by a Poisson distribution, satisfactory performance of calling ASM can be achieved when the total read counts for methylated SNPs are at least 7, that is, sequencing depth greater than 7. If there is strong evidence of over-dispersion in the data and the Negative Binomial distribution has to be used, satisfactory sensitivity of calling ASM requires a larger sequencing depth (at least 9).

Our method has the merit of easy and fast computation. After obtaining the read counts from the sequencing data, the probabilities of ASM can be readily computed for multiple SNPs in a parallel fashion since all parameters in the Bayesian models are either pre-specified based on biology background or estimated based on count data before calculating the probabilities of ASM. It took about 15 minutes to run the R script for the prostate cell data on a Mac computer with a 2.4 GHz CPU and 4GB memory.

Our method defines genotype-dependent methylation states, and considers ASM as a cross-genotype event. Inference for ASM combines the posterior probabilities of methylation for different genotypes multiplicatively. An alternative is to set up a hierarchical model and define four overall methylation states for each SNP: no methylation, A-ASM, B-ASM and allele-free methylation. Such a model, when properly constructed coherently, is conceptually appealing. However, for practical data with high noise and often conflicting observations across genotypes, the alternative model could be vulnerable and sensitive to modeling assumptions, and deserves further research. Another extension would be to simultaneously estimate the model parameters and compute the posterior probabilities of ASM. Skelly et al (2011) [30] proposed a Bayesian hierarchical model to profile allele specific gene expression (ASE) based on RNA-seq data. ASE is also a form of allele asymmetry, where the two alleles have differential expression levels. RNA-seq data are similar to bisulfite-based DNA methylation sequencing data. The general hypothesis of ASE is that the proportion of the reads mapped to one allele differs from 0.5. Therefore the model in [30] can be adapted to ASM detection when bisulfite-based methylation data are available. On the other hand, enrichment-based methylation data do not quantify methylation level as RNA-data do for gene expression, since they often require a binary call of methylation, which is represented by the latent variable sg in our model. To develop a full Bayesian approach, we need to consider non-degenerated prior distributions for the parameters, including αgs and λgs for the Poisson-Binomial model (or μgs and φgs for the NB-Binomial model) for g = 0, 1, 2 and sg = s. Such a full Bayesian approach would require careful elicitation of the hyper-parameters in the prior distributions, and the computation cost will increase due to the need of Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations for inference. Since our goal is to perform a fast screen for ASM, we delay the investigation of a full Bayesian approach for future research.

DNA methylation is known to occur mainly in CpG islands [31] or island shores [32]. There are 225,659 known SNPs on the CpG sites. For each SNP identified with ASM, bisulfite sequencing may be applied to further validate the methylation state of each CpG site within a local genomic region around that SNP. Zhang et al (2009) [33] also observed that ASM may occur in genomic regions that do not contain any SNPs based on bisulfite sequencing data. To identify regions unmarked by SNPs based on enrichment-based NGS data, it requires knowing the count of short reads overlapping with each CpG site on the two alleles. However, the sequencing reads currently available are generally not long enough so that for some short reads that overlap with CpG sites, whether they are mapped to A allele or B allele is unknown. For example, for a genomic region marked by a SNP, our model is not able to make use of the short reads that are just one base-pair way from this SNP. The rapid development of the NGS technologies is expected to solve these issues and our future research will include extending the current method to determine arbitrary genomic regions with allele specific methylation. Another future direction is to account for the effect of copy number variation (CNV). An underlying assumption for our model is that read counts are mainly driven by methylation signal but not CNV. In the prostate cell line study, the method proposed by Wang et al. (2007) [15] was applied to identify genomic regions with possible CNV. To limit false discovery due to CNV, SNPs that lie in the regions identified with CNV were not considered in the analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers and the Associated Editor for their helpful comments, which significantly improve the quality of this manuscript. The work is partially funded by National Cancer Institute (CA154356).

Contributor Information

Yuan Ji, Email: yji@northshore.org.

Angela H Ting, Email: tinga@ccf.org.

References

- 1.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: How the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nature Genetics. 2003;33:245–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson KD. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature. 2007;447:433–40. doi: 10.1038/nature05919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes & development. 2002;16(1):6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerkel K, Spadola A, Yuan E, Kosek J, Jiang L, Hod E, Li K, Murty VV, Schupf N, Vilain E, Morris M, Haghighi F, Tycko B. Genomic surveys by methylation-sensitive SNP analysis identify sequence-dependent allele-specific DNA methylation. Nature genetics. 2008;40:904–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tycko B. Allele-specific DNA methylation: beyond imprinting. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19:R210–20. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoemaker R, Deng J, Wang W, Zhang K. Allele-specific methylation is prevalent and is contributed by CpG-SNPs in the human genome. Genome research. 2010;20:883–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.104695.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Rohde C, Tierling S, Jurkowski TP, Bock C, Santacruz D, Ragozin S, Reinhardt R, Groth M, Walter J, Jeltsch A. DNA methylation analysis of chromosome 21 gene promoters at single base pair and single allele resolution. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirst M, Marra MA. Next generation sequencing based approaches to epigenomics. Briefings in functional genomics. 2010;9(5–6):455–65. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Down TA, Rakyan VK, Turner DJ, Flicek P, Li H, Kulesha E, Gärf S, Johnson N, Herrero J, Tomazou EM, Thorne NP, Bäckdahl L, Herberth M, Howe KL, Jackson DK, Miretti MM, Marioni JC, Birney E, Hubbard TJ, Durbin R, Tavare S, Beck S. A Bayesian deconvolution strategy for immunoprecipitation-based DNA methylome analysis. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26(7):779–85. doi: 10.1038/nbt1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacinto FV, Ballestar E, Esteller M. Methyl-DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP): hunting down the DNA methylome. BioTechniques. 2008;44(1):35–43. doi: 10.2144/000112708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serre D, Lee BH, Ting AH. MBD-isolated Genome Sequencing provides a high-throughput and comprehensive survey of DNA methylation in the human genome. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:391–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris RA, Wang T, Coarfa C, Nagarajan RP, Hong C, Downey SL, Johnson BE, Fouse SD, Delaney A, Zhao Y, Olshen A, Ballinger T, Zhou X, Forsberg KJ, Gu J, Echipare L, O’Geen H, Lister R, Pelizzola M, Xi Y, Epstein CB, Bernstein BE, Hawkins RD, Ren B, Chung WY, Gu H, Bock C, Gnirke A, Zhang MQ, Haussler D, Ecker JR, Li W, Farnham PJ, Waterland RA, Meissner A, Marra MA, Hirs M, Milosavljevic A, Costello JF. Comparison of sequencing-based methods to profile DNA methylation and identification of monoallelic epigenetic modifications. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28(10):1097–105. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome biology. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang K, Li M, Hadley D, Liu R, Glessner J, Grant SF, Hakonarson H, Bucan M. PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome research. 2007;17(11):1665–74. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laurent L, Wong E, Li G, Huynh T, Tsirigos A, Ong CT, Low HM, Kin Sung KW, Rigoutsos I, Loring J, Wei CL. Dynamic changes in the human methylome during differentiation. Genome research. 2010;20:320–31. doi: 10.1101/gr.101907.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Jeltsch A. The Application of Next Generation Sequencing in DNA Methylation Analysis. Genes. 2010;1:85–101. doi: 10.3390/genes1010085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degner JF, Marioni JC, Pai AA, Pickrell JK, Nkadori E, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. Effect of read-mapping biases on detecting allele-specific expression from RNA-sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(24):3207–12. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaranek AW, Levanon EY, Zecharia T, Clegg T, Church GM. A survey of genomic traces reveals a common sequencing error, RNA editing, and DNA editing. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1000954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaFramboise T. Single nucleotide polymorphism arrays: a decade of biological, computational and technological advances. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37:4181–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Y, Wang W, Li Y, Tu J, Bai Y, Xiao P, Zhang D, Lu Z. Identification of methylated regions with peak search based on Poisson model from massively parallel methylated DNA immunoprecipitation-sequencing data. Electrophoresis. 2010;31(21):3537–44. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu M, Lu AY. The counter-intuitive noninformative prior for the Bernoulli family. Journal of Statistical Education. 2004;12:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leisch F. FlexMix: A general framework for finite mixture models and latent class regression in R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2004;11(8) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji H, Jiang H, Ma W, Johnson DS, Myers RM, Wong WH. An integrated software system for analyzing ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq data. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26(11):1293–300. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Triantaphyllou E. Multi-Criteria Decision Making: A Comparative Study. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers (Springer); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton MA, Noueiry A, Sarkar D, Ahlquist P. Detecting differential gene expression with a semiparametric hierarchical mixture method. Biostatistics. 2004;5:155–76. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/5.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller P, Parmigiani G, Robert C, Rousseau J. Optimal sample size for multiple testing: the case of gene expression microarrays. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2004;99:990–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Müller P, Parmigiani G, Rice K. FDR and Bayesian multiple comparisons rules. In: Bernardo J, et al., editors. Bayesian Statistics. Vol. 8. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skelly DA, Johansson M, Madeoy J, Wakefield J, Akey JM. A powerful and flexible statistical framework for testing hypotheses of allele-specific gene expression from RNA-seq data. Genome research. 2011;21(10):1728–37. doi: 10.1101/gr.119784.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(6):3740–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052410099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, Cui H, Gabo K, Rongione M, Webster M, Ji H, Potash JB, Sabunciyan S, Feinberg AP. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shore. Nature genetics. 2009;41(2):178–86. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Rohde C, Reinhardt R, Voelcker-Rehage C, Jeltsch A. Non-imprinted allele-specific DNA methylation on human autosomes. Genome biology. 2009;10(12):R138. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-12-r138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.