Abstract

The major surface glycoprotein (Msg), which is the most abundant protein expressed on the cell surface of Pneumocystis organisms, plays an important role in the attachment of this organism to epithelial cells and macrophages. In the present study, we expressed Pneumocystis jirovecii Msg in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a phylogenetically related organism. Full-length P. jirovecii Msg was expressed with a DNA construct that used codons optimized for expression in yeast. Unlike in Pneumocystis organisms, recombinant Msg localized to the plasma membrane of yeast rather than to the cell wall. Msg expression was targeted to the yeast cell wall by replacing its signal peptide, serine-threonine–rich region, and glycophosphatidylinositol anchor signal region with the signal peptide of cell wall protein α-agglutinin of S. cerevisiae, the serine-threonine–rich region of epithelial adhesin (Epa1) of Candida glabrata, and the carboxyl region of the cell wall protein (Cwp2) of S. cerevisiae, respectively. Immunofluorescence analysis and treatment with β-1,3 glucanase demonstrated that the expressed Msg fusion protein localized to the yeast cell wall. Surface expression of Msg protein resulted in increased adherence of yeast to A549 alveolar epithelial cells. Heterologous expression of Msg in yeast will facilitate studies of the biologic properties of Pneumocystis Msg.

Keywords: Pneumocystis jirovecii, major surface glycoprotein, upstream conserved sequence, antigenic variation, GPI anchored protein

Pneumocystis is a genus of opportunistic pathogens that cause pneumonia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients, as well as other immunocompromised patients [1, 2]. This genus is genetically divergent: each host species is infected by a genetically distinct strain that represents Pneumocystis species, with Pneumocystis jirovecii infecting humans, Pneumocystis carinii infecting rats, and Pneumocystis murina infecting mice [3–6]. Major surface glycoprotein (Msg; also called “gpA”), is the most abundant surface protein of Pneumocystis organisms and is encoded by a multicopy gene family [7–10]. Msg expression is regulated by a single expression site encoding the upstream conserved sequence (UCS), which contains a signal peptide that likely directs the protein to the endoplasmic reticulum for subsequent processing, including cleavage of the UCS, glycosylation, and surface export [11–15]. Msg variants are related but unique and potentially permit the organism to vary its surface antigen as a means of evading host immune defenses [16].

In yeast, many cell surface proteins are glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)–anchored proteins that are covalently linked to cell wall glucans. Msg has features characteristic of GPI-anchored proteins, including a signal peptide at the UCS and a hydrophobic tail at the C-terminus. The latter can function as a GPI anchor in mammalian cell systems [17]. Msg may play an important role in host-parasite interactions by mediating adherence of Pneumocystis organisms to host alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages [18–20]. In vitro studies to better define the interaction of Pneumocystis organisms with host lung alveolar epithelial cells are limited because of the lack of an efficient culture system for Pneumocystis species. Heterologous expression of epithelial adhesion protein (Epa1) of Candida glabrata, a GPI-anchored cell wall protein, has been used to study adherence properties of this protein to cultured human epithelial cells [21]. In the present study, we undertook to express Msg on the cell wall of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, an organism that is phylogenetically related to Pneumocystis organisms and to test its ability to mediate adherence to a lung alveolar epithelial cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Strains, Culture, and Transformation

S. cerevisiae strain YPH 499 was obtained from Stratagene (Santa Clara, CA). Yeasts were grown at 30°C in yeast peptone dextrose adenine medium. For plasmid maintenance, synthetic dextrose medium without uracil (SD dropout medium) was used. Yeast cultures were grown overnight in 2% raffinose instead of dextrose, before inducing protein expression in 2% galactose for 4 hours. Transformation was carried out using lithium acetate as described in the pESC Yeast Epitope Tagging Vectors instruction manual (Stratagene).

Construction of msg Expression Plasmid

A DNA construct using S. cerevisiae codon preference was synthesized (GenScript USA, Piscataway, NJ) to encode full-length Msg, including the UCS (GenBank accession no. AF321555), followed by a P. jirovecii Msg variant, Msg 32 (corresponding to bp 21–3080 of GenBank accession no. AF033212), that was randomly selected from previously cloned Msg variants [22]. A cloning artifact stop codon (TGA) present at 3027–3029 bp of Msg 32 was modified to TGG. A hemagglutinin (HA) tag, a histidine (His) tag, and an enterokinase site were added between the UCS and Msg variable region.

The synthesized insert was cloned into S. cerevisiae vector pESC-URA (Stratagene), which has a GAL1 promoter. The insert with or without the UCS sequence was also cloned into the destination vector, pBC542 (a kind gift from Dr Brendan Cormack) (GenBank accession no. EU418980), using Gateway technology with the Clonase II kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). The 3′ end of the construct (corresponding to 2772–3080 bp of msg 32) was deleted before cloning into pBC542, which contains sequences coding for the serine-threonine–rich region (338–580 amino acids; GenBank accession no. AAQ82691) of epithelial adhesin (Epa1) of C. glabrata, followed by sequences coding for 21–92 amino acids of Cwp2 (GenBank accession no. EEU05144), a cell wall protein of S. cerevisiae. The vector has a tef1 promoter and encodes 3 HA epitopes upstream of Epa1 [23]. We added sequences encoding a FLAG epitope immediately after the signal peptide.

A construct encoding 59 amino acids (corresponding to 917–975 amino acids of Msg 32) of the serine-threonine–rich region of Msg was synthesized by Genscript. Four repeats of the same sequence were used to replace the Epa1 sequence in the vector.

In certain cases, the Msg signal peptide (MRVALFALSAQVGCA) was replaced with the signal peptide (MFTFLKIILWLFSLALA) of α-agglutinin (GenBank accession no. AAA34417.1), a cell wall–anchored surface protein of S. cerevisiae [24], using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

PCR was performed using AccuPrime Pfx (Invitrogen) or High Fidelity PCR master mix (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). For Gateway cloning, the amplification was performed using primers with attB1 sites. General PCR conditions were as described previously [25].

Site-Directed Mutagenesis and DNA Sequencing

All mutations and deletions were done using the QuikChange II or QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the guidelines of the manufacturer. Plasmid DNA preparations made using the QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were sequenced using an ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA).

Preparation of Spheroplasts

To make spheroplasts, the CelLytic Y Plus Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used. Yeast cells transformed with the msg constructs or vector alone were grown to mid-log phase, and the cells were treated with β-1,3 glucanase until spheroplast formation was complete. Spheroplasts were centrifuged at 9300 × g for 5 minutes. The pellet containing spheroplasts was used for immunofluorescent staining and Western blot analysis, and the supernatant was used for Western blot analysis.

Preparation of Cell Membranes and Deglycosylation

Spheroplasts resuspended in extraction buffer (CelLytic Y Plus Kit, Sigma-Aldrich) containing protease inhibitor (P8849, Sigma-Aldrich) were disrupted using glass beads, followed by centrifugation at 1020 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The pellet (cell debris and nuclei) was analyzed by Western blot. The supernatant was centrifuged at 150 000 ×g for 30 minutes at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant (cytosol fraction) and pellet (cell membrane) were also analyzed by Western blot.

To deglycosylate N-linked oligosaccharides, proteins extracted from the cell membrane fraction were denatured for 10 minutes, incubated with N-linked-glycopeptide-(N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminyl)-L-asparagine amidohydrolase (PNGase F) for 1 hour at 37°C (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), and analyzed by Western blot.

β-1,3 Glucanase Digestion and Protein Extraction

Yeast cells expressing Msg on the surface were treated with β-1,3 glucanase (lyticase, CelLytic Y Plus Kit, Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 37°C. The supernatant obtained was analyzed by Western blot, and the pellet was used for immunofluorescence analysis. In some experiments, yeast cells expressing Msg were broken with glass beads to prepare cell extracts for Western blot analysis.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described [25]. The blots were probed with a 1:200 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using BM Blue POD Substrate, precipitating (Roche Diagnostics).

Immunofluorescence Microscopic Analysis

Intact yeast cells or spheroplasts were added to individual wells of 8-well slides and then were heat fixed. Samples were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), followed by incubation with a 1:100 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 37°C for 1 hour. The slides were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), dried, and sealed with coverslips with anti-fade mounting medium. Images were collected using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse E800, Barber Optics, Columbia, MD).

Flow Cytometry

Yeast cells expressing Msg were incubated with 1:10 dilution of FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4°C for 60 minutes, washed with PBS, fixed with 2% formaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry, using FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose CA).

Yeast Cell Adherence Assay

Yeast cells transformed with msg-pESC-URA vector or empty vector were grown overnight at 30°C and then induced with galactose for 4 hours. To fluorescently label the cells, 2 µL of 5 mM carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) solution (CellTrace CFSE cell proliferation kit, Molecular Probes) in 100 µL of 0.5 M sodium acetate (pH 4.0), was added to 900 µL of the cells (1.0 OD600/mL). The cells were incubated at 30°C for 1 hour, 500 µL of cold culture medium was added, and the cells were incubated on ice for 5 minutes. The cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 500 µL of PBS containing 2% dextrose. Labeling efficiency was checked under a fluorescence microscope.

A549 epithelial cells (ATCC, CCL-185) were cultured in 6-well plates in F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Before the adherence assay was performed, the medium was changed to one without FBS. Labeled yeast cells were added to the culture, and adherence was initiated by brief centrifugation. After the cells were incubated for 1 hour, the nonadherent cells were removed by washing 3 times with PBS. The epithelial cells along with adherent yeast cells were scraped in PBS, and the fluorescence was measured by a fluorometer (Wallac Victor 3, PerkinElmer, Santa Clara, CA).

RESULTS

Characterization of P. jirovecii Msg Expression in S. cerevisiae

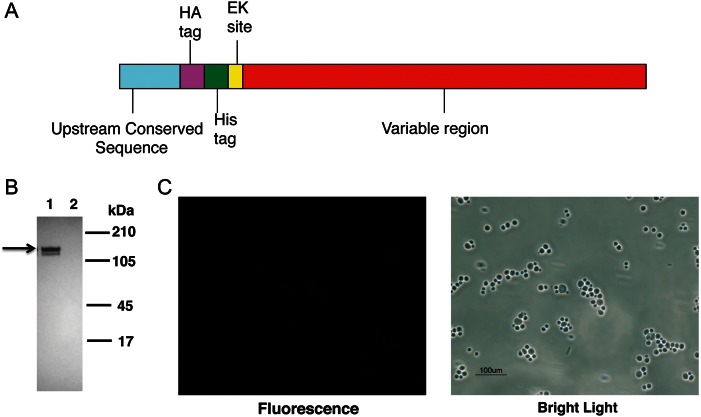

A DNA construct encoding the full-length Msg 32 open reading frame, including the UCS, was synthesized using codons optimized for expression in S. cerevisiae [11, 22]. The schematic diagram of the construct is shown in Figure 1A. The construct was cloned into pESC-URA vector and transformed into yeast. Vector alone (no insert) served as a negative control. After 4 hours of galactose induction, Western blot analysis of cell extracts by using an anti-HA tag antibody identified 2 bands of the expected size, approximately 130 kDa (Figure 1B); no reactivity was seen with the no insert control. To determine whether recombinant Msg is expressed on the cell surface, yeast cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy, using FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody; no fluorescence was seen (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Recombinant Msg protein expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae does not localize to the cell wall. A, Schematic diagram of the Pneumocystis jirovecii msg construct that was inserted in pESC-URA vector. The hemagglutinin (HA) tag, histidine (His) tag, and enterokinase site were added between the upstream conserved sequence and variable region of msg. B, Western blot analysis of expressed protein, using peroxidase-conjugated anti-HA antibody. Protein extracts prepared from cells transformed with msg construct (lane 1) showed immunoreactivity to 2 approximately 130-kDa bands (arrow), while extracts from cells transformed with vector alone (lane 2) showed no immunoreactivity. C, Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis of yeast cells expressing Msg using FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody. The cells expressing Msg showed no fluorescence when viewed under UV light, indicating that Msg is not expressed on the yeast cell wall. Yeast cells can be seen under bright light.

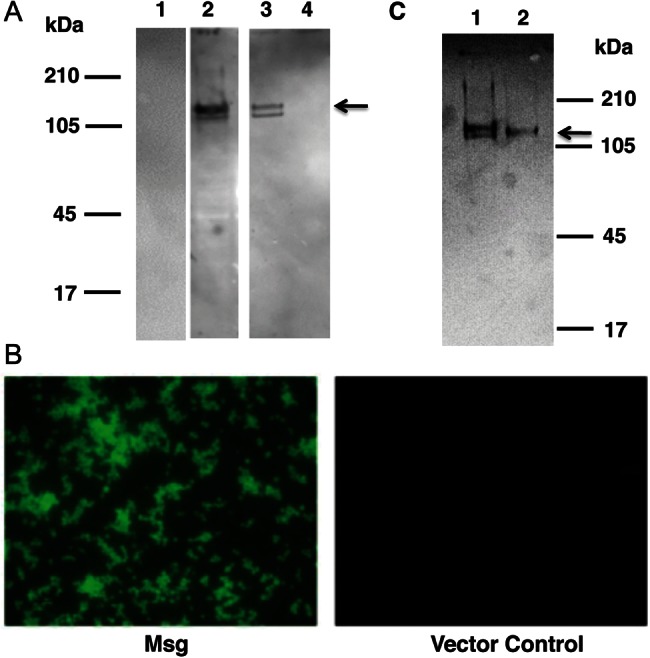

Additional studies were undertaken to localize Msg. Galactose-induced yeast cells were treated with β-1,3 glucanase to digest the cell wall, followed by centrifugation to separate spheroplasts from the digested cell wall products. Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibody showed that Msg is expressed within the spheroplasts and not in the cell wall (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Expressed Msg is localized to the plasma membrane of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and is glycosylated. Yeast cells transformed with Msg or vector alone were treated with β-1,3 glucanase, and the supernatant containing the digested cell wall and the pellet containing spheroplasts were separated by centrifugation. Spheroplasts were further fractionated to yield cell membranes and the cytosol. A, Western blot analysis of the cell fractions, using anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody. Spheroplasts (lane 2) and the cell membrane (lane 3) fraction showed immunoreactivity to 2 approximately 130-kDa bands (arrow). No immunoreactivity was seen with digested cell wall (lane 1) or the cytosol preparation (lane 4). B, Immunofluorescence microscopic analysis of spheroplasts using fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-HA antibody. Spheroplasts prepared from yeast cells expressing Msg showed fluorescence, while cells transformed with vector alone showed no fluorescence. C, Western blot analysis of Msg before and after deglycosylation. Proteins extracted from the cell membrane fraction, which contains Msg, were treated with pNGase F prior to Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibody. Untreated Msg migrates as 2 close bands (lane 1); following deglycosylation, there is a single band (lane 2) that is slightly smaller than the higher molecular weight band seen in lane 1.

To further localize Msg, spheroplasts were fractionated by vortexing with glass beads, followed by low-speed centrifugation to eliminate nuclei and cell debris and then by high-speed centrifugation to separate cell membrane from cytosol. By Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibody, Msg was localized to the cell membrane fraction (Figure 2A); no reactivity was seen with the cytosol fraction. Immunofluorescence microscopy using FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody verified that Msg was expressed on the cell membrane of spheroplasts (Figure 2B). Thus, full-length Msg expressed in yeast is localized to the plasma membrane and not the cell wall.

Because recombinant Msg showed 2 bands in Western blot analysis and because native Msg is known to be glycosylated [19], we explored the possibility that differential glycosylation accounted for the 2 bands. Deglycosylation with pNGase F resulted in the disappearance of the higher-sized band, indicating that recombinant Msg is glycosylated in yeast (Figure 2C).

Mutation of the GPI Cleavage Site Does Not Change the Localization of Expressed Msg

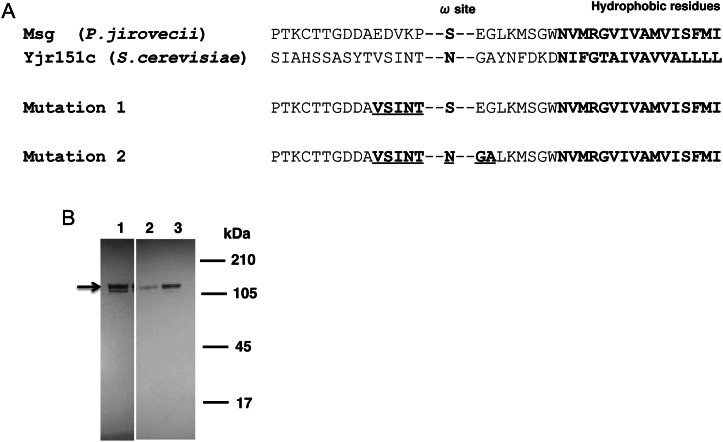

In Pneumocystis organisms, Msg is a cell surface protein that can be released by glucanase treatment [7]. In yeast, most proteins extracted by glucanase treatment are attached to the glucan of the cell wall through a modified GPI moiety [26, 27]. The C-terminal of the precursor to GPI-anchored proteins has an anchor attachment signal with an anchor attachment site (ω-site), a hydrophilic region followed by a hydrophobic region of 10–15 amino acid residues [28]. In yeast, amino acids flanking the ω-site help determine whether protein is localized to the cell wall or cell membrane [29, 30]. We thus mutated the amino acids near or at the putative ω-site of Msg to determine whether that would be sufficient to allow localization to the cell wall, using as a template the sequence in yjr151c, a GPI-dependent cell wall protein of S. cerevisiae [29] (Figure 3A). Two sets of mutations were performed. In the first, amino acid residues EDVKP of Msg at ω-minus site were replaced by VSINT. In the second, the VSINT replacement was maintained, the putative ω-site was changed from S to N, and the 2 amino acid residues downstream of the ω-site, EG, were replaced by GA (Figure 3A), to more closely resemble the ω-site and flanking regions of yjr151c, given that these may be important for GPI anchoring [31]. By Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibody, both mutated proteins were expressed in yeast (Figure 3B). However, no immunoreactivity was detected on the yeast surface (data not shown). To see whether the native signal peptide prevented cell wall localization, we replaced the Msg signal peptide in constructs with mutation 1 and 2 with the signal peptide of α-agglutinin, a cell wall–anchored protein of S. cerevisiae. Again there was no localization to the cell wall (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Mutation of amino acids at the putative ω-site region of Pneumocystis jirovecii Msg does not alter the localization of expressed Msg. A, Alignment of C-terminal amino acid residues of P. jirovecii Msg with that of yjr151c, a glycophosphatidylinositol-dependent cell wall protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The protein sequences for the 2 mutated constructs are shown below the alignment. The hydrophobic amino acid residues and the amino acid at the potential ω-site are shown in bold. The mutated amino acids are shown in bold and underlined. B, Western blot analysis using anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody. Cells transformed with the original construct (lane 1), mutation 1 (lane 2), and mutation 2 (lane 3) all expressed recombinant Msg in yeast, as shown by immunoreactivity to an approximately 130-kDa band (arrow) in Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibody, but showed no surface reactivity by immunofluorescent staining (data not shown).

Surface Expression of Msg in Yeast

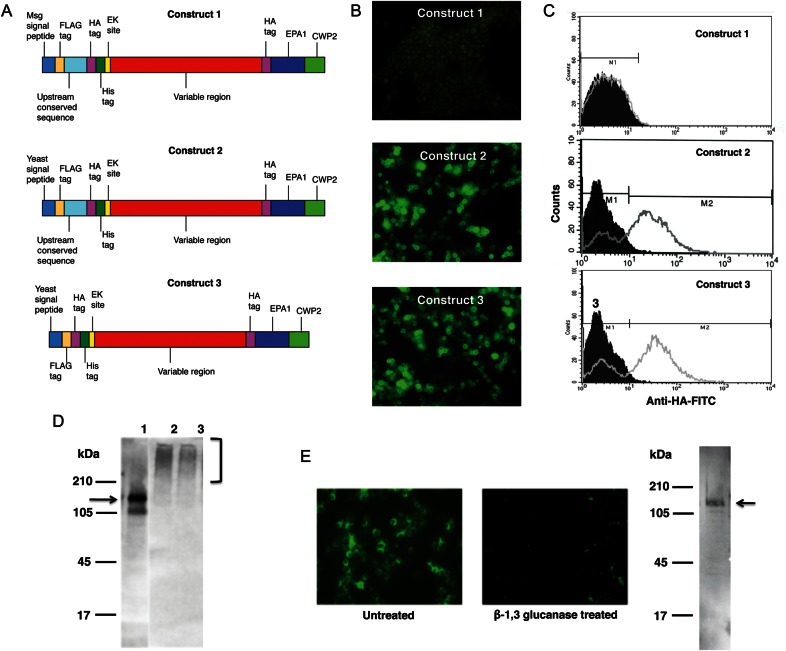

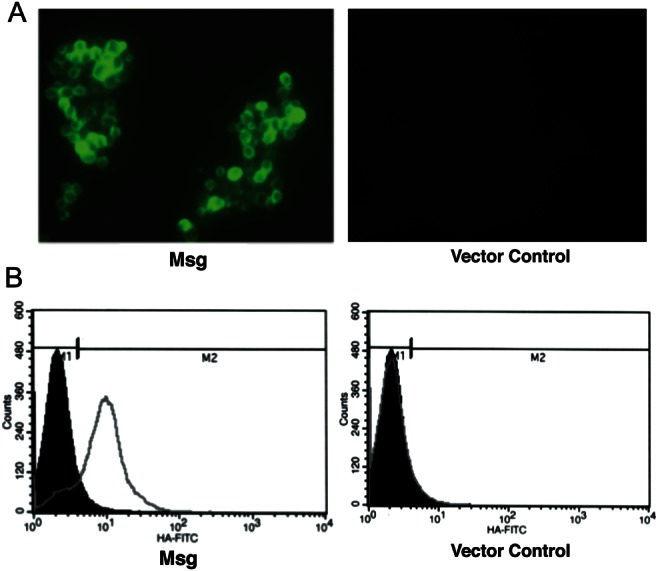

To target the expression of Msg to the cell wall of yeast, we used pBC542, which contains sequences that code for the serine-threonine–rich region of epithelial adhesin (Epa1) of C. glabrata followed by the C-terminal domain of cell wall protein (Cwp2) of S. cerevisiae. Fusion proteins with inserts upstream of these regions are expressed on the cell surface of S. cerevisiae [23]. We generated 3 different constructs to express the Msg fusion protein (Figure 4A). All constructs included a near full-length (1–2771 bp of msg 32) codon–biased msg sequence; the deleted region (2772–3080 bp) encodes a serine-threonine–rich region and a GPI anchor signal. Construct 1 also included a region encoding the Msg signal peptide and UCS. In construct 2 the Msg signal peptide was replaced by a yeast signal peptide, and in construct 3 the UCS sequence was deleted from construct 2. By immunofluorescence, cell surface expression of Msg was observed only for yeast cells transformed with constructs 2 and 3, which included the yeast signal peptide (Figure 4B). To confirm the cell surface expression of the protein, we analyzed the cells by flow cytometry. When cells were transformed with constructs 2 and 3, approximately 70% showed cell surface immunofluorescence, while construct 1 showed no fluorescence (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Targeting Msg to the yeast cell wall using pBC542 vector. A fragment of the msg gene was cloned into pBC542 vector, which contains sequences encoding a serine-threonine–rich region of Epa1 of Candida glabrata followed by sequences encoding the carboxyl region of Cwp2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. A, The schematic diagram of 3 DNA constructs used for expression in pBC542. The Msg fragment (1–2771 bp of msg 32) excludes a serine-threonine–rich region and the glycophosphatidylinositol anchor signal of Msg. Construct 1 includes the entire upstream conserved sequence (UCS) of Msg, as well as most of the variable region. In construct 2, the Msg signal peptide in construct 1 was replaced by a yeast signal peptide. In construct 3, the UCS sequence through the predicted cleavage site was removed from construct 2, while the yeast signal peptide was retained. B, Immunofluorescence microscopic analysis of yeast transformants. Cells transformed with constructs 2 and 3 showed immunofluorescence when stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody, suggesting cell wall localization of expressed Msg fusion protein. No fluorescence was detected when cells were transformed with construct 1. C, Flow cytometric analysis using FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody. FITC-conjugated nonspecific antibody (mouse immunoglobulin G) was used as negative control. The histogram shows the cell counts on the y-axis and fluorescence intensity on the x-axis. The solid histogram shows nonspecific staining with the negative control, and the open histogram shows specific staining with the anti-HA antibody. The staining of cells transformed with construct 1 was similar to that of the negative control, while cells transformed with construct 2 and construct 3 showed immunofluorescence staining of approximately 70% of the cells. D, Western blot analysis of protein extracts prepared from cells following disruption with glass beads. Cells expressing construct 1 showed immunoreactivity to an approximately 150-kDa band (expected size is shown by the arrow) when probed with anti-HA antibody (lane 1), while cells expressing construct 2 (lane 2) and construct 3 (lane 3) showed a high molecular weight smear (bracket), indicating that the protein is still attached to the cell wall. E, Immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis of protein extracts prepared from cells expressing construct 3 following treatment with β-1,3 glucanase. Immunofluorescence reactivity in untreated cells is lost following β-1,3 glucanase treatment. Glucanase treatment solubilizes recombinant Msg, which now migrates as an approximately 150-kDa band (arrow), rather than as the high molecular weight smear that was seen following glass bead disruption.

By Western blot, immunoreactivity to an approximately 150-kDa band was seen with protein extracts prepared from cells transformed with construct 1, while protein extracts prepared from cells transformed with constructs 2 and 3 showed higher molecular weight smears (Figure 4D), indicating that the recombinant protein is still attached to remnants of the cell wall. Thus, construct 1 is expressed but not transferred to the surface, while the other 2 constructs are expressed on the surface of yeast.

Yeast cells expressing Msg were resuspended in buffer with or without β-1,3 glucanase and incubated overnight at 37°C. The pellet (residual yeast cells) obtained after centrifugation was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 4E). Untreated cells showed fluorescence, while glucanase-treated cells showed little fluorescence. By Western blot, an approximately 150-kDa band was detected in the glucanase-treated supernatant after centrifugation, demonstrating that Msg was released from the cell wall.

Msg Serine-Threonine–Rich Region Does Not Target the Yeast Cell Wall

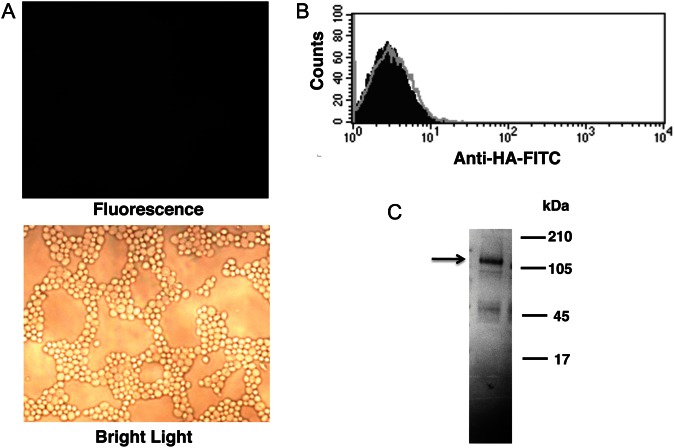

A long serine-threonine–rich region (200–300 amino acids) appears to play an important role in localizing proteins to the yeast cell wall [21]. To see whether sequences encoding the serine-threonine–rich region of P. jirovecii Msg could function in this manner, we replaced the serine-threonine–rich region of Epa1 encoded in construct 2 with 4 repeats (59 amino acids each) of the Msg serine-threonine–rich region. No reactivity was seen by immunofluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry in yeast transformed with this construct (Figure 5A and 5B). Western blot analysis demonstrated that the Msg fusion protein is expressed, with immunoreactivity to an approximately 150-kDa band (Figure 5C). Thus, the serine-threonine–rich region of Msg was unable to target localization of the expressed fusion protein to the cell wall.

Figure 5.

Replacing the Epa1 serine–threonine–rich region with a serine-threonine–rich region of Msg disrupts cell wall localization of Msg fusion protein. The Epa1 sequence of construct 2 (Figure 4) was replaced by a sequence encoding 4 repeats (59 amino acids each) of the Msg serine-threonine–rich region. Protein expression in transformed yeast cells was analyzed by immunofluorescence and Western blot. A, Immunofluorescence microscopic analysis using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody showed no surface fluorescence, while multiple organisms are seen by bright light. B, Flow cytometric analysis of yeast cells stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody. The histogram shows the cell counts on the y-axis and fluorescence intensity on the x-axis. Solid histogram shows nonspecific staining with the negative control (mouse immunoglobulin G), and the open histogram shows specific staining with the anti-HA antibody. Consistent with the microscopic results, no specific staining is seen. C, By Western blot analysis, an approximately 150-kDa band is seen when probed with anti-HA antibody, demonstrating that the fusion protein is expressed.

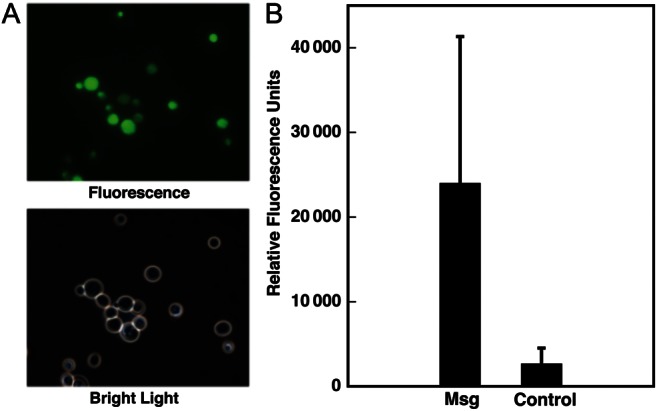

Yeast Expressing Msg Show Increased Adherence

To improve expression, the insert from construct 3 was cloned into pESC–URA vector downstream of the GAL1 promoter. Following induction with galactose, the cell surface expression was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 6A). Cells transformed with the msg construct showed fluorescence when stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody, while cells transformed with vector alone showed no immunoreactivity. Approximately 84% of the cells showed immunofluorescence when analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 6B) as compared to 70% with the tef1 promoter.

Figure 6.

Improved cell surface expression of Msg fusion protein under the control of gal1 promoter. Construct 3 (Figure 4A) was cloned into pESC-URA vector downstream of the gal1 promoter. After 4 hours of galactose induction, the yeast transformants were analyzed for the cell surface expression of Msg by immunofluorescence, using fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody. A, Immunofluorescence microscopic analysis. Cells transformed with the msg construct showed immunofluorescence, whereas cells transformed with vector alone showed no fluorescence. B, Flow cytometric analysis. The histogram shows the cell counts on the y-axis and fluorescence intensity on the x-axis. Solid histogram shows nonspecific staining with the negative control (mouse immunoglobulin G), and the open histogram shows specific staining with the anti-HA antibody. Approximately 84% of the cells showed surface expression of the Msg fusion protein; vector alone showed no staining.

This construct was used to determine whether Msg could mediate adherence. Yeast cells expressing Msg were labeled with CFSE to facilitate quantitation of adherent organisms; fluorescent microscopy verified labeling of most cells (Figure 7A). Labeled cells were added to cultured A549 epithelial cells grown in 6-well plates. After incubation for 1 hour, yeast cells expressing Msg showed an approximately 9-fold increase in adherence as compared to the negative control (vector with no insert; Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Yeast cells expressing Msg on the cell surface adhere to A549 epithelial cells. Cells transformed with msg construct 3 expressed in pESC-URA or vector alone were stained with carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and then tested for their ability to adhere to cultured A549 epithelial cells. A, Fluorescence microscopic analysis demonstrates that most of the yeast cells visible under bright light are stained with CFSE. B, Yeast cells expressing Msg show increased adherence to epithelial cells. After 1 hour of incubation with CSFE-labeled yeast, followed by washing, epithelial cells and adherent yeast were scraped, and fluorescence was quantitated with a fluorometer. Results are the mean of 2 experiments. The error bar represents the SD. Although the results are not significant, in both experiments yeast cells expressing Msg showed an approximately 9-fold higher fluorescence as compared to those transformed with vector alone.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we expressed a full-length P. jirovecii Msg for the first time, using a yeast expression system. We found that in this heterologous system the native protein sequence targeted Msg to the cell membrane rather than to the cell wall; we also demonstrated that modification of the signal peptide, as well as the serine-threonine–rich region plus the GPI anchor, resulted in cell wall expression. While the mechanism of expression in yeast is likely different from mechanisms used by Pneumocystis organisms, expression in yeast provides a tool to facilitate studies of the biological properties of Msg.

We were previously unsuccessful in expressing full-length Msg in different expression systems, including bacteria, yeast, and baculovirus, and thus used fragments of the gene to produce recombinant proteins. Possible reasons for the failure may be the large size of Msg, the lack of codon optimization, or the potential toxicity to the cells because of the presence of multiple cysteine residues. In the current study, the msg DNA sequence was optimized to accommodate the S. cerevisiae codon preference.

The goal of our studies was to express Msg in yeast to ultimately allow us to study host cell–Msg interactions. Given the close phylogenetic relationship between the organisms [32], we hypothesized that Msg expressed in S. cerevisiae would be processed as in Pneumocystis organisms, where it is targeted to an external location in the cell wall. However, we found that recombinant Msg using the native protein sequence was not expressed on the surface but localized to the plasma membrane. Msg has a signal peptide at the N-terminal and a hydrophobic tail at the C-terminal, which are characteristics of GPI-anchored proteins. The ferret Pneumocystis Msg hydrophobic tail has been shown to function as a GPI signal in Cos cells [17]. While the GPI anchor targets a plasma membrane location in many organisms, in yeast most GPI proteins are attached to the cell wall, using a GPI remnant that links to the β-glucan of the cell wall [29]. Based on localization of recombinant Msg to the plasma membrane, the native hydrophobic leader and tail sequences appear to serve as true GPI signals in yeast but are inadequate to lead to cell wall localization. In yeast, amino acid residues V, I, or L at the ω-4/5 site and Y or N at the ω-2 site may act as a signal for cell wall incorporation [30]. However, modification of both the leader and the putative ω-site and flanking amino acids to yeast sequences that, in other studies, target a cell wall location in yeast, was insufficient to allow Msg to localize to the cell wall.

We were ultimately able to target the expression of recombinant Msg protein, excluding the serine-threonine–rich region and GPI anchor signal, to the yeast cell wall by using a vector (pBC542) that contains sequences encoding the serine-threonine–rich region of Epa1, an epithelial adhesin of C. glabrata, and the carboxyl region of the cell wall protein (Cwp2) of S. cerevisiae, which contains a yeast GPI-anchor sequence [23]. Cell wall expression also required a yeast signal peptide. The cell wall localization was confirmed by immunofluorescence analyses and by solubilization of the expressed Msg protein with β-1,3 glucanase treatment.

Most GPI cell wall proteins appear to have a long serine-threonine–rich region in the carboxy half of the protein that allows extension of the protein to the cell surface [21]. In C. glabrata, proteins containing <100 amino acids in a serine-threonine–rich region are not expressed on the cell surface [33]. Msg has a serine-threonine–rich region that contains only 59 amino acid residues. To see whether a longer Pneumocystis-specific region could function to target the cell wall in yeast, we replaced the serine-threonine–rich region of Epa1 with 4 tandem repeats of the Msg serine-threonine–rich region; however, this again was insufficient to localize Msg to the cell wall. It thus appears that the domains that presumably allow Msg to be expressed on the surface of Pneumocystis organisms, including the signal peptide, the serine-threonine–rich region, and the carboxy terminal GPI signal, are not processed by yeast in a similar manner.

The recombinant Msg protein that was expressed on the yeast cell wall increased adhesion of yeast to A549 alveolar epithelial cells, as measured by a binding assay using CFSE-labeled yeast cells. Msg has previously been reported to mediate the binding of Pneumocystis organisms to alveolar epithelial cells [18, 20]. This adherence assay could be used to further investigate the role of Msg in host-organism interactions.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Kovacs JA, Masur H. Evolving health effects of Pneumocystis: one hundred years of progress in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2009;301:2578–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas CF, Jr, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stringer JR, Stringer SL, Zhang J, Baughman R, Smulian AG, Cushion MT. Molecular genetic distinction of Pneumocystis carinii from rats and humans. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:733–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinclair K, Wakefield AE, Banerji S, Hopkin JM. Pneumocystis carinii organisms derived from rat and human hosts are genetically distinct. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;45:183–4. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazars E, Guyot K, Durand I, et al. Isoenzyme diversity in Pneumocystis carinii from rats, mice, and rabbits. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:655–60. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma L, Imamichi H, Sukura A, Kovacs JA. Genetic divergence of the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase genes in Pneumocystis carinii from 7 different host species. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1358–62. doi: 10.1086/324208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovacs JA, Powell F, Edman JC, et al. Multiple genes encode the major surface glycoprotein of Pneumocystis carinii. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6034–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garbe TR, Stringer JR. Molecular characterization of clustered variants of genes encoding major surface antigens of human Pneumocystis carinii. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3092–101. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3092-3101.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haidaris PJ, Wright TW, Gigliotti F, Haidaris CG. Expression and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding an immunodominant surface glycoprotein of Pneumocystis carinii. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1113–23. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright TW, Bissoondial TY, Haidaris CG, Gigliotti F, Haidaris PJ. Isoform diversity and tandem duplication of the glycoprotein A gene in ferret Pneumocystis carinii. DNA Res. 1995;2:77–88. doi: 10.1093/dnares/2.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutty G, Ma L, Kovacs JA. Characterization of the expression site of the major surface glycoprotein of human-derived Pneumocystis carinii. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:183–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edman JC, Hatton TW, Nam M, et al. A single expression site with a conserved leader sequence regulates variation of expression of the Pneumocystis carinii family of major surface glycoprotein genes. DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15:989–99. doi: 10.1089/dna.1996.15.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunkin SM, Stringer JR. Translocation of surface antigen genes to a unique telomeric expression site in Pneumocystis carinii. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:283–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.375905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada M, Sunkin SM, Stringer JR, Nakamura Y. Antigenic variation by positional control of major surface glycoprotein gene expression in Pneumocystis carinii. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1563–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunkin SM, Linke MJ, McCormack FX, Walzer PD, Stringer JR. Identification of a putative precursor to the major surface glycoprotein of Pneumocystis carinii. Infect Immun. 1998;66:741–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.741-746.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop LR, Helman D, Kovacs JA. Discordant antibody and cellular responses to Pneumocystis major surface glycoprotein variants in mice. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-13-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guadiz G, Haidaris CG, Maine GN, Simpson-Haidaris PJ. The carboxyl terminus of Pneumocystis carinii glycoprotein A encodes a functional glycosylphosphatidylinositol signal sequence. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26202–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.26202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limper AH, Pottratz ST, Martin WJ., 2nd Modulation of Pneumocystis carinii adherence to cultured lung cells by a mannose-dependent mechanism. J Lab Clin Med. 1991;118:492–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lundgren B, Lipschik GY, Kovacs JA. Purification and characterization of a major human Pneumocystis carinii surface antigen. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:163–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI114966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pottratz ST, Paulsrud J, Smith JS, Martin WJ., 2nd Pneumocystis carinii attachment to cultured lung cells by Pneumocystis gp 120, a fibronectin binding protein. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:403–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI115318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frieman MB, Cormack BP. Multiple sequence signals determine the distribution of glycosylphosphatidylinositol proteins between the plasma membrane and cell wall in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 2004;150:3105–14. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mei Q, Turner RE, Sorial V, Klivington D, Angus CW, Kovacs JA. Characterization of major surface glycoprotein genes of human Pneumocystis carinii and high-level expression of a conserved region. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4268–73. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4268-4273.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zupancic ML, Frieman M, Smith D, Alvarez RA, Cummings RD, Cormack BP. Glycan microarray analysis of Candida glabrata adhesin ligand specificity. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:547–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipke PN, Wojciechowicz D, Kurjan J. AG alpha 1 is the structural gene for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin, a cell surface glycoprotein involved in cell-cell interactions during mating. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3155–65. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutty G, Achaz G, Maldarelli F, et al. Characterization of the meiosis-specific recombinase Dmc1 of Pneumocystis. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1920–9. doi: 10.1086/657414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Groot PW, Ram AF, Klis FM. Features and functions of covalently linked proteins in fungal cell walls. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:657–75. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapteyn JC, Montijn RC, Vink E, et al. Retention of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall proteins through a phosphodiester-linked beta-1,3-/beta-1,6-glucan heteropolymer. Glycobiology. 1996;6:337–45. doi: 10.1093/glycob/6.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pittet M, Conzelmann A. Biosynthesis and function of GPI proteins in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:405–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamada K, Terashima H, Arisawa M, Kitada K. Amino acid sequence requirement for efficient incorporation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-associated proteins into the cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26946–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamada K, Terashima H, Arisawa M, Yabuki N, Kitada K. Amino acid residues in the omega-minus region participate in cellular localization of yeast glycosylphosphatidylinositol-attached proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3886–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3886-3889.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nuoffer C, Horvath A, Riezman H. Analysis of the sequence requirements for glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchoring of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gas1 protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10558–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edman JC, Kovacs JA, Masur H, Santi DV, Elwood HJ, Sogin ML. Ribosomal RNA sequence shows Pneumocystis carinii to be a member of the fungi. Nature. 1988;334:519–22. doi: 10.1038/334519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frieman MB, McCaffery JM, Cormack BP. Modular domain structure in the Candida glabrata adhesin Epa1p, a beta1,6 glucan-cross-linked cell wall protein. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:479–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]