Abstract

Pluripotency and stemness is believed to be associated with high Oct-3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2 (ONS) expression. Similar to embryonic stem cells (ESCs), high ONS expression eventually became the measure of pluripotency in any cell. The threshold expression of ONS genes that underscores pluripotency, stemness, and differentiation potential is still unclear. Therefore, we raised a question as to whether pluripotency and stemness is a function of basal ONS gene expression. To prove this, we carried out a comparative study between basal ONS expressing NIH3T3 cells with pluripotent mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (mBMSC) and mouse ESC. Our studies on cellular, molecular, and immunological biomarkers between NIH3T3 and mBMSC demonstrated stemness property of undifferentiated NIH3T3 cells that was similar to mBMSC and somewhat close to ESC as well. In vivo teratoma formation with all three germ layer derivatives strengthen the fact that these cells in spite of basal ONS gene expression can differentiate into cells of multiple lineages without any genetic modification. Conclusively, our novel findings suggested that the phenomenon of pluripotency which imparts ability for multilineage cell differentiation is not necessarily a function of high ONS gene expression.

Introduction

Ability to isolate and establish pluripotent or multipotent stem/precursor population is a major objective for the biotechnological industry and clinical translation of regenerative medicine. A major impediment for using stem cells in a clinical setup is poor availability of cells, especially those obtained with noninvasive procedures without raising much ethical issues. These limitations greatly restrict the usage of stem cells in clinics, disabling treatments of many degenerative diseases. This lacuna can be filled if any tissue-specific cells can be verifiably demonstrated to possess pluripotent or multipotent capacity. This may elevate the hope to find a well-suited stem cell-like cell line that can serve as an autologous, noncontroversial, and renewable source for cell therapy without ethical and immunological concerns, which are usually associated with embryonic stem cells (ESCs).

Numerous gene and protein expression criteria have been set for recognizing a cell as pluripotent. Microarray analyses have demonstrated a set of various transcripts that are associated with stemness as in the case of ESCs [1]. Notably, it has been demonstrated by Yamanaka and colleague that the combinations of four major transcription factors, Oct-3/4, Nanog, Sox-2, and Klf-4, is indispensable for the cells to maintain pluripotency as in the case of ESCs [2,3]. However, there are some other reports which indicate that expressions of not all the four genes are essential to maintain the stemness. According to NIH and ISSCR guidelines, teratoma formation is one of the major criteria for classifying a cell to be pluripotent [4]. Apart from this, the presence of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is another reliable property shown for pluripotent cells such as ESCs [1,5].

In principle, a cell that is able to differentiate into cell types of all three germinal layers is considered pluripotent. On the other hand, a multipotent cell can give rise to cells originating from the same germ layer [6]. A classic example of a stem cell with pluripotent and multipotent potential is mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). MSCs can differentiate into various cell types. Depending on isolation procedure and tissue source, both pluripotent and multipotent type of stem cells can be isolated [7]. Mesenchymal cells display fibroblastic cell morphology and express vimentin protein as a characteristic marker along with high Oct-3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2 (ONS) expression [8]. Bone marrow MSC (BMSC) isolated from crude bone marrow are reported to possess pluripotent gene expression and also show tri-lineage differentiation [9–12]. Therefore, it appears that BMSC can serve as a model that is used for screening various cell types for their degree of stemness. Hence, cells which portray specific features that are in accordance with the parameters mentioned earlier can be designated as pluripotent cells.

In a very recent report, Wang et al. exemplify that ONS genes are the core regulators of pluripotency. This group showed that Oct4 regulates and interacts with the BMP4 pathway to specify four developmental fates. High levels of Oct4 enable self-renewal in the absence of BMP4; Nanog represses embryonic ectoderm differentiation but has little effect on other lineages, whereas Sox-2 is redundant and represses mesendoderm differentiation. Thus, instead of being panrepressors of differentiation, each factor controls specific cell fates [13]. Numerous cell types isolated from tissues and organs such as heart, kidney, liver, lungs, brain, pancreas, spleen, muscles, adipose tissue, dental pulp, placenta, and amnion are now being tested on the parameters mentioned earlier with an aim of generating patient-specific pluripotent stem cell lines for treating various incurable degenerative diseases.

With numerous published reports, it becomes a general belief that pluripotency, stemness, and differentiation potential into trigerminal lineages are associated with high levels of ONS genes, but this does not explain the fact that many low ONS expressing cells can also demonstrate multilineage differentiation potential, high ALP staining, and a teratoma-like structure formation and, hence, generate valid questions. (1) What should be the threshold of ONS gene expression for any cell to be pluripotent? (2) Is pluripotency really a function of high ONS gene expression or can basal level expressing cells also show lower but sustained pluripotency? Attempts are made in the present study to answer these questions scientifically using NIH3T3 as a model and are compared with high ONS expressing cells.

NIH3T3 cells, isolated from Swiss albino mice [14], are not known as stem cells due to the reduced expression of pluripotency-associated genes despite being embryonic in nature. These cells have been extensively used as a model system for various molecular, cellular, and toxicological studies [15–18] and are considered differentiated dermal fibroblast cells. Many groups used NIH3T3 as control cells that fail to differentiate [19–21]. However, their differentiation into adipocytes, myocytes, and neural cell types has been reported either after transforming genetically or if differentiated under defined media conditions [19–21]. Piestun et al. reported that NIH3T3 cells after being transfected with Nanog show induced pluripotency and expressed markers that are specific to various differentiating cell types [22]. In 2006, Yamanaka and colleagues also compared pluripotent ESCs and untransformed NIH3T3 by a microarray analysis and concluded that although these cells did not express pluripotency genes, especially the four crucial ones, that is, Oct3/4, Nanog, Sox-2, and Klf4; they expressed c-Myc [3]. However, this group neither examined nor commented on the multipotent nature of these cells. Later, in 2008 and 2009, Deng and colleagues published two reports demonstrating differentiation of untransformed NIH3T3 cells into oesteocytes and neuronal cell types in bone and spinal cord injury mouse models [1,23,24]. Two other groups also reported that NIH3T3 can give rise to neural cells and oesteoblasts, respectively [21,25]. Recently, our group also reported pancreatic islet cell differentiation of untransformed NIH3T3 with appropriate induction [26].

To answer these questions and to understand whether pluripotency can also be associated with basal ONS gene expression, we carried out a comparative study of basal ONS expressing NIH3T3 cells with pluripotent mouse BMSC (mBMSC) and mouse ESC (mESC). We carefully examined NIH3T3 cells for pluripotent and multipotent stem cell specific markers and compared them with those of mBMSC and mESC with regard to morphological features, expression profile of stemness related genes, ability to undergo multilineage differentiation, and in vivo teratoma formation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Balb/c mice, 3–4 weeks old, weighing around 25–30 g, were used for transplantation and bone marrow cell isolation experiments. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with our institutional ‘‘Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments'’ and CPCSEA guidelines and regulations.

Chemicals and cell culture media

All chemicals, media, and antibodies used in this study were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Molecular biology reagents and cDNA and PCR kits were procured from Fermentas Inc. All plasticwares were purchased from Nunc, Inc.

Isolation of marrow-derived MSCs

Bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells were isolated from 4 week-old Balb/c mice according to Zhu et al. [10,27]. Mice were sacrificed after proper anaesthesia. Briefly, tibia and femur bones were dissected under sterile conditions. The metaphyseal ends of the bones were cut, and the marrow plugs were flushed out by passing low glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (L-DMEM) (Sigma) through a needle inserted into one end of the bone. Bone marrow cells from mice were collected; big tissue debris were removed with the help of a cell strainer and were then seeded in low-glucose RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 2 days.

Purification and propagation of MSCs

MSCs were purified as described earlier [10,27]. Briefly, the cultured cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/mL in complete medium (high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma), penicillin (100 IU/mL), streptomycin (100 IU/mL; MP Biological, Inc.) in polystyrene T25 culture flasks and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 48 h. Loosely attached hematopoietic cells were discarded on trypsinizing adherent cells for 5 min. Cells that remained adhered were trypsinized for another 7 min [27] and then cultured in complete medium for 10 days. The cell media was replaced with fresh one every third day. The cells were trypsinized using Trypsin-EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and passaged in T75 flasks until the second generation became 70%–90% confluent. Cultured mBMSC were then characterized and used for a comparative study with NIH3T3 after ensuring their pluripotency.

Cell culture and maintenance

NIH3T3 cells were obtained from three different sources (Cell Repository, National Centre for Cell Science, Pune, India, ATCC procured cells from Zydus Pharmaceuticals, Ahmedabad, India and a generous gift from Dr. Girish M. Shah's lab, Laval University. Quebec, Canada) and were maintained in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were split into a 1:1 ratio in new tissue culture flasks on being about 90% confluent. Culture media was changed after every 2 days.

Cell count and growth curve

Fully confluent mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells were trypsinized with 0.1% Trypsin EDTA solution and counted under an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Nikon TE2000). One hundred thousand cells were seeded into each well of 24-well plates for growth curve studies. Cells were eventually trypsinized and counted at different time points (0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h). Cell counts were then plotted versus time to establish the growth curve of cells. Growth curve of NIH3T3 cells was compared with that of mBMSC. Doubling time of both the cells were also determined using the algorithm ln (Nt−N0) ln (t), where Nt and N0 were number of cells at final time point and at initial seeding point, respectively, and t was time period in hours for which cell counts were recorded.

MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay

Cell proliferation rate and effect of cytotoxic agent [dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO)] were determined by MTT assay (Roche). NIH3T3 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 50,000 cells per well in complete medium. MTT reagent was added in culture in each well after 24 h of incubation with different concentrations of DMSO. The optical density values were analyzed 4 h after the MTT reaction using Multiskan PC (Thermo Lab), and cell survival curves were then plotted against time in culture.

H&E staining

Cells were trypsinized and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution. A histological examination was carried out by standard histological techniques. Fixed cells were stained with H&E stain, and observations were recorded under a light microscope.

Transfection and GFP labeling

Before carrying out an in vivo teratoma assay, we transfected NIH3T3 cells with GFP harboring plasmid p-eGFP-N1 (Clontech), so that the cells could be differentiated from those of the host. One hundred thousand cells were transfected with 1 μg p-eGFP-N1 plasmid DNA using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as a transfecting agent in a 1:3 volume ratio in a 3.5 cm2 dish, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following the transfection, stably GFP expressing clones were selected by growing them in media containing G418 at 300 μg/mL concentration for the first 2 days and thereafter in 900 μg/mL G418 for the next 7 days. Clones were purified from isolated colonies using clonal discs and scaled up for subcutaneous transplants with agarose plugs in Balb/c mice.

Teratoma formation

For each graft, ∼0.2 million GFP expressing NIH3T3 cells, washed and resuspended in 300 μL DMEM complete medium, were injected subcutaneously into Balb/c mice (maintained in MSU in-house animal house facility) in 1.5% melted agarose [28–30]. Visible tumors, after 2 weeks of transplantation, were dissected and fixed overnight with 4% PFA solution. The tissues were then paraffin embedded, sectioned, stained with H&E, and, the sections were examined for the presence of cells that were representatives of all three germ layers produced by NIH3T3-eGFP cells [31].

ALP staining

ALP staining of spheroids of both NIH3T3 and mBMSC origin was carried out with BCIP/NBT stain. Cell clusters were mechanically isolated, and cells were dissociated with trypsin EDTA digestion for 5 min at 37°C. After washing with 10% FBS and then with PBS, the cells were fixed with 2% PFA solution for 5 min and stained with NBT/BCIP [1]. 3T3L-1 cells served as controls.

Immunocytochemistry

An immunocytochemical analysis was performed for various stem/progenitor markers in both cell types as previously described [32,33]. Cells were seeded on glass coverslips in high-glucose DMEM complete medium and allowed to adhere for 3–4 h. After attachment, cells were fixed with 4% PFA solution for 10 min at room temperature. After permeabilizing them with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, the cells were incubated in blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin and 4% FBS in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies were added in blocking solution, and coverslips were incubated overnight at 4°C. A list of the antibodies used and their dilutions are given in Table 1. Cells were then washed thrice with washing buffer (1:10 dilution of blocking buffer in PBS) and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to FITC and TRITC flurophores (Sigma Aldrich) in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. For negative controls, cells were incubated with normal IgG. Cells were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). Fluorescence imaging was carried out by using a Nikon TES2000 microscope. All images were analyzed with the help of NIH element software supplied by Nikon Japan.

Table 1.

Antibody Information Chart

| Name of antibody | Company | Mono/polyclonal | Molecular weight (kDa) | Source | Dilution for WB | Dilution for ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-actin | Thermo Scientific | Mono | 42 | Mouse | 1:5,000 | NA |

| E-Cadherin | Cell Signaling | Mono | 135 | Rabbit | 1:1,000 | 1:200 |

| Fibronectin | Sigma | Mono | 220 | Rabbit | 1:1,000 | 1:800 |

| Ki-67 | Sigma | Mono | 345/395 | Mouse | 1:1,000 | 1:800 |

| Ngn-3 | Santa Cruz | Mono | 27 | Mouse | 1:1,000 | NA |

| Nestin | Sigma Aldrich | Mono | 177 | Rabbit | 1:1,000 | 1:250 |

| Pdx1 antibody | Cell Signaling | Mono | 42 | Rabbit | 1:1,000 | 1:250 |

| α-SMA | Sigma | Mono | 42 | Mouse | 1:1,000 | 1:250 |

| Vimentin | Sigma | Mono | 53 | Mouse | 1:1,000 | 1/250 |

| Oct3/4-PE | BD | Mono | 32 | mouse | 1:1,000 | 1:200 |

| Nanog | BD | Mono | 42 | mouse | 1:1,000 | 1:200 |

| Sox-2-APC | BD | Mono | 38 | Mouse | 1:1,000 | 1:200 |

| CD44-PE | BD | Mono | — | Mouse | — | 1:200 |

SMA, smooth muscle actin; PDX-1, pancreatic duodenal homeobox gene-1; Ngn-3, neurogenin-3; WB, western blot; ICC, immunocytochemistry.

RNA extraction and semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRizol Reagent (Sigma Aldrich), and 5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA and subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification for various stem cell genes according to conditions mentioned in Tables 2 and 3. Optimal conditions for PCR were determined by running gradient PCR performed with a range of annealing temperature from 51°C–60°C. One microliters of cDNA products was used to amplify genes using Fermentas 2×master mix containing 1.5 μL Taq Polymerase, 2 mM dNTP, 10×Tris, glycerol reaction Buffer, 25 mM MgCl2, and 20 pM appropriate forward and reverse primers for each gene. PCR products were then resolved on a 1.5% Agarose gel (Sigma Aldrich) and visualized with ethidium bromide staining. Images were analyzed using Alpha Imager software (UVP Image Analysis Software Systems).

Table 2.

Primer Sequences for Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

| Name of gene | Gene accession no. | Primer sequence forward | Primer sequence reverse | PCR conditions (Tm) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct-3/4 | NM_013633.2 | GGCGTTCGCTTTGGAAAGGTGTTC | CTCGAACCACATCCTTCTCT | 60 | 431 |

| Nanog | NM_028016.2 | TACCTCAGCCTCCAGCAGAT | GAAGTTATGGAGCGGAGCAG | 57 | 411 |

| α-SMA | NT_039687.7 | AGTCGCCATCAGGAACCTCGAG | ATCTTTTCCATGTCGTCCCAGTTG | 60 | 296 |

| Vimentin | NT_039202.7 | AGCGGGACAACCTGGCCG | GGGAAGAAAAGGTTGGCAGAGGC | 58 | 744 |

| Nestin | NT_039240.7 | GCGGGGCGGTGCGTGACTAC | AGGCAAGGGGGAAGAGAAGGATGT | 58 | 326 |

| PDX-1 | NT_039324.7 | CTC GCT GGG AAC GCT GGA ACA | GCT TTG GTG GAT TTC ATC CAC GG | 55 | 229 |

| Ngn-3 | NT_039500.7 | ACTAGGATGGCGCCTCATCCCTTG | GGTCTCTTCACAAGAAGTCTGAGA | 57 | 658 |

| GAPDH | NT_166349.1 | CAAGGTCATCCATGACAACTTTG | GTCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG | 58 | 496 |

Table 3.

Primer Sequences for mESC Pluripotency Gene Profile by Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

| Serial No. | Gene accession no. | Gene symbol | Primer sequences (forward & reverse) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NT_166349.1 | GAPDH | 5′-TCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCCA-3′ 5′-ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATTCA-3′ |

| 2 | NM_013633.2 | Oct-4 | 5′-GCTCTCCCATGCATTCAAAC-3′ 5′-TGTCTACCTCCCTTGCCTTG-3′ |

| 3 | NM_011443 | Sox-2 | 5′-ATGGCCCAGCACTACCAGAG-3′ 5′-CTTCTCCAGTTCGCAGTCCA-3′ |

| 4 | NM_028016.2 | Nanog | 5′-TTTGGAAGCCACTAGGGAAAG-3′ 5′-AAGCCCAGATGTTGCGTAAGT-3′ |

| 5 | NM_011920 | ABCG2 | 5′-CCATAGCCACAGGCCAAAGT-3′ 5′-GGGCCACATGATTCTTCCAC-3′ |

| 6 | NM_006086 | β-III Tubulin | 5′-GGAACATAGCCGTAAACTGC-3′ 5′-TCACTGTGCCTGAACTAACTTACC-3′ |

| 7 | NM_144841 | Otx2 | 5′-GCTGGCTCAACTTCCTACT-3′ 5′-TCCAAGCAGTCAGCATTGAAG-3′ |

| 8 | NM_008090.5 | GATA-2 | 5′-GCAGAGAAGCAAGGCTCGC-3′ 5′-CAGTTGACACACTCCCGGC-3′ |

| 9 | NM_003181 | Brachyury (T) | 5′-ATAACGCCAGCCCACCTACT-3′ 5′-TGGTACCATTGCTCACAGACC-3′ |

| 10 | NM_008092 | GATA-4 | 5′-TCAAATTCCTGCTCGGACTTGGGA-3′ 5′-GTTTGAACAACCCGGAACACCCAT-3′ |

| 11 | NM_008814 | PDX-1 | 5′-ACTTAACCTAGGCGTCGCACAAGA-3′ 5′-GGCATCAGAAGCAGCCTCAAAGTT-3′ |

Real-time quantitative PCR

cDNA, synthesized by using Maxima First-Strand Reverse Transcription System Kit (Fermentas, Inc.), was used for real-time analysis (Applied- Biosystem Step One™ Real-Time PCR Sequence detection System) of pluripotent stem cell gene expression. The primer sequences used for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) are listed in Table 4. qRT-PCRs were performed in two independent experiments in triplicates. Five microliters of total reaction volume containing 2.5 μL Maxima SYBR-Green Master-mix (Fermentas, Inc.), 20 pM of each forward and reverse primers using 100 ng cDNA (1/20th of total cDNA preparation) was used. PCR amplification program was 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, and 1 min at 54°C–57°C). All qRT-PCR results were normalized to the level of beta-actin determined in parallel reaction mixtures to correct for differences in RNA input. Fold changes by qRT-PCR gene expression were analyzed using Step One™ software V.2.2.2 (Applied Biosystems, Inc.), which led to a possible estimation of the actual fold change (down-regulation after setting mBMSC expression to base in log10). The qRT-PCR results are mean±SEM of RQ values versus target gene.

Table 4.

Primer Sequences for Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

| Name of gene | Gene accession no. | Primer sequence forward | Primer sequence reverse | PCR conditions (Tm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct-3/4 | NM_013633.2 | AACCTTCAGGAGATATGCAAATCG | AACCTTCAGGAGATATGCAAATCG | 54 |

| Nanog | NM_028016.2 | TACCTCAGCCTCCAGCAGAT | GAAGTTATGGAGCGGAGCAG | 57 |

| Sox-2 | NM_011443.3 | CTGCAGTACAACTCCATGACCAG | GGACTTGACCACAGAGCCCAT | 54 |

| Beta-actin | NM_007393.3 | ACGAGGCCCAGAGCAAGAG | GGTGTGGTGCCAGATCTCCTC | 57 |

FACS analysis for ONS markers

Cultures of fixed mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells were examined for the presence of ONS markers in their normal cell culture condition. Cells were stained in solution using a mixture of OCT-3/4-PE, Nanog (unlabeled), and Sox-2-APC-labeled antibodies. Unstained cell samples included unlabeled cells, cells labeled with secondary FITC-conjugated antibody alone (for Nanog only), and single fluorochrome-labeled cells. Cells were analyzed using an FACS Aria III (BD Biosciences) with a 70 μM nozzle and 70 PSI pressure conditions. Cells were first gated based on forward and side scatter properties and then compared with unstained negative cells for levels of OCT-3/4 and Sox-2 labeling. Cells stained with Nanog were compared with secondary antibody control cells at FITC channel. All the calculations and statistics were performed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Inc.).

Protein extraction and western blotting

Western blotting analysis of both NIH3T3 cells and mBMSC at two different passages was performed as previously described [3]. Both NIH3T3 cells and mBMSC were lysed with urea containing lysis buffer (1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 70 mM NaCl, 1% Triton, and 50 mM NaF) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Fermentas, Inc.). Protein estimation in all samples was carried out using Bradford reagent according to the manufacturer's suggestions (Bio-Rad). Cell lysates (50 μg) were separated on Polyacrylamide gel using Mini-tetrapod electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto nitrocellulose blotting membrane (Thermo, Inc.). Blots were then incubated with blocking milk buffer (5% fat-free skimmed milk with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS). Dilutions of primary antibodies used, against various stem cell genes, is listed in Table 1. Primary antibodies were added to blots and incubated overnight at 4°C. Anti-rabbit and Anti-mouse IgG conjugated with HRP were used to develop the blots using ultra-sensitive-enhanced chemiluminiscence reagent (Millipore) and imprinted on X-ray films.

Results

To determine whether pluripotency is a function of ONS gene expression and whether basal ONS gene expression can contribute to multilineage differentiation potential, a comparative study of NIH3T3 cells was done with pluripotent mBMSC and mESC. Stemness in NIH3T3 was monitored in cells procured from three independent sources (as mentioned earlier, cells showed normal karyotyping, see Supplementary Fig. S3; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd), after which the presence of stemness-related genes was screened separately with cells obtained from each individual source at both mRNA and protein levels. In this study, we have monitored and compared growth curve, doubling time, and growth kinetics of NIH3T3 cells with that of mBMSC. Presence of various proteins and gene expression profile of pluripotent, multipotent, self-renewal, and differentiation-related genes were also carried out. Here, we also examined in vivo differentiation potential and phenotypic features for pluripotent stem cells with specific reference to teratoma formation and trigerminal layer representatives.

BMSC isolation provided purified MSC

We successfully isolated mBMSC from bone marrow of mice by employing the surgical procedure used by Hsiao and Cheng et al. [27]. A homogeneous population of mBMSC, without hematopoietic or macrophage contaminations, was achieved by differential trypsinization technique, one of the major steps in the isolation and purification procedure, and as a result of it, long-term cultures of mBMSC could be established. The number of nucleated marrow cells obtained after isolation was around 3.26±0.31×107 per mouse, which was comparable to that reported by Hsiao and Cheng et al. 2010 [29]. One of the most important factors in determining the establishment of a long-term culture of mBMSC was the cell density in the starting culture. mBMSC were seeded at a density of 0.2 million nucleated cells/cm2 and were then allowed to attach to the surface of the plates for 2 days in low-glucose RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, which prevented the adherence of contaminating undesired cells. Nonadherent cells were easily removed when the medium was changed on day 3, and confluent colonies were observed by day 8 (P1). Once passaged, in addition to mBMSC, a large number of contaminating small spherical cells, called lymphohaematopoietic cells, engaged in mBMSC colonies as a second layer were also observed (Fig. 2. P#3; P#5). Purification of mBMSC was achieved with the property that they can be removed from the plastic surface within 5 min in response to trypsin, while for hematopoietic ones, it takes 8 min. However, trypsin-lifted cells still contained a few hematopoietic cells. When seeded at a density of 50,000 cells/cm2 in the next passage, these hematopoietic cells did not adhere to the plastic surface and were eradicated from the culture on subsequent passaging (Fig. 2: P3 to P10 for gradual purification of mBMSC). The differential trypsinization steps were repeatedly done till P8. To ensure pure population of mBMSC, different characterization and comparative studies were carried out on cells obtained after P10.

FIG. 2.

Phase-contrast images demonstrate step-wise purification of mBMSC from P0 to P10: figure P0 represents mBMSC after isolation at day 1 with heterogeneous population of cells. The other images represent step-wise purification, subsequent removal of stem cells, and gradual depletion of hematopoietic in cultures of mesenchymal cells from P1 to P9. Phase-contrast photomicrograph at P10 shows purified population of bone marrow mesenchymal cells.

Morphological studies and H&E staining showed stem-cell-like features in NIH3T3 cells

Both NIH3T3 and mBMSC were cultured in high-glucose DMEM with 10% FBS in the absence of any growth factor or growth supplements and sub-cultured when they became about 70% confluent to ensure continued availability of log phase culture conditions for both the cell types. All the characterizations for comparative studies were performed in their native and untransformed state. Morphologically, NIH3T3 cells attain basic fibroblastic morphology, as explained by Todaro and Green [14], similar to that of fibroblastic mBMSC (Fig. 1a, d). In confluent cultures, NIH3T3 cells progressively formed a monolayer and got interlaced with each other, which was similar to the case of mBMSC. Since these cells showed neoplastic behavior, we observed an absence of contact inhibition and cells continued to grow to form multiple layers when cultured for a longer period of time. H&E staining of NIH3T3 cells showed rapidly dividing nuclei and cells with high chromatin content (Fig. 1c). All these observations are in congruence with the previous report by Todaro and Green [14]. A comparison of the morphological behavior of NIH3T3 cells with mBMSC demonstrated many similarities between the two cell types in cell shape, pattern of growth, cell contacts, and proliferative nature.

FIG. 1.

Phase contrast and H&E stain photomicrographs of NIH3T3 cells and mBMSC. (a) Represents cells in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium complete medium at 37°C and 5% CO2. (b, c) Represent H&E stained NIH3T3 cells at 200×magnifications. Images represent fibroblastic cell morphology. Encircled arrow marked cells show mitotically dividing nuclei with high chromatin content. (d) Represents phase-contrast photomicrograph of mBMSC at P10. mBMSC, mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells.

Spheroid body formation with ALP staining indicated in vitro differentiation potential in NIH3T3 cells

Next, in order to determine the in vitro differentiation potential of NIH3T3 cells, we carried out ALP staining of the spheroid body from two cell types, as it is more important to characterize these cells based on recent ISSCR guidelines and other reports available from current literature. Spheroid bodies were generated by seeding high cell density in a minimum surface area in plates without any coating with growth factors. As expected, most of the cells adhered, and some of them died; these were excluded from the culture on medium replenishment. Varying sizes of small to large spheroid bodies were formed in each cell type by day 3–5, and these were very similar to embryoid bodies (EBs) formed from ESCs. On comparing, NIH3T3 cells showed similar features to mBMSC, which are in accordance to Yamanaka and Riekstina's group [2]. The floating spheroids from both cell types were collected and stained for ALP. We noticed that NIH3T3 cells formed spheroids and remained intensely positive for ALP, similar to mBMSC and mESC, confirming the pluripotent nature of these cells [2]. Normal 3T3-L1 cells served as a control that was negative for ALP (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

ALP staining in NIH3T3 and mBMSC: (a, b) represents typical spheroid formation after 8 day culture in absence of any growth factor supplement (arrowhead). (c, d) Represent positive ALP staining in cell clusters generated in both cell types (marked with arrowhead). (e, f) Represent magnified view of clusters (marked with arrowhead). (g) Represents stained embryoid bodies from mESC (shown with arrowhead) and (h) represents 3T3-L1 cells as negative control. mESCs, mouse embryonic stem cells; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Growth curve and kinetics (cumulative duplication number and doubling measurement) of NIH3T3 demonstrated growth pattern identical to mBMSCs

Healthy cells from sub-confluent cultures of both cell types were plated in 24-well plates and used for determining the population doubling potential, progression, and proliferative activity. Cumulative population doublings were calculated by considering the initial number of NIH3T3 and mBMSC cells seeded at 0 h and the number of cells harvested at each destined time point, respectively, without passaging (Graph 2). These observations provide a theoretical growth curve that is directly proportional to the cell number. With the help of the curve generated, doubling time was found to be 27.53±3.4 h and 21.87±2.39 h for NIH3T3 and mBMSC, respectively, suggesting that both the cells have more or less a similar population doubling time. A small but insignificant 1.2-fold difference was found in their doubling time (Graph 3), which is in accordance with Todaro and Green [14]. A correlation analysis curve of both cell systems, from a log-scale graph, gave a trendline that agreed with the linear curve equation, that is, y=mx+c. The regression value (R2 value) of both curves was found to be 8.9 and 8.2, respectively, suggesting no significant difference in growth patterns of the two cell systems.

GRAPH. 1–5.

Growth curves and growth kinetics of NIH3T3 and mBMSC: Graphs represent comparative growth pattern and proliferation of NIH3T3 cells and mBMSC. Kinetics graph represents the correlation of growth pattern of both cell systems fitting in a linear curve equation. n=4.

Cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assays revealed stemness behavior of NIH3T3 cells

For determining the proliferative nature of NIH3T3 cells and their tolerance to a cytotoxic material such as DMSO, MTT assay was employed. NIH3T3 cells were cultured in 96-well plates and were allowed to grow for 72 h. At regular time intervals of 24 h each, MTT reagent was added and optical density was recorded. We found that starting from 24 to 72 h, NIH3T3 cells proliferated aggressively with a fold change of 2.8 from 0 to 24 h and of 2.78 from 24 to 72 h, respectively (Graph 4). It has been notably shown that cytotoxicity tolerance of DMSO is evidently much higher in stem cells rather than in normal differentiated ones. It is worth mentioning that differentiated cells can tolerate optimal DMSO concentration up to 0.5%; however, peripheral blood mononuclear cells and MSCs are shown to tolerate DMSO even till 5% [34,35]. When carefully observed, these cells were found to have enormous tolerance for potent cytotoxic agents DMSO. Unexpectedly, NIH3T3 cells showed tolerance to DMSO even at 5% with ∼50% viability. The cells were growing normally in media containing 5% of DMSO. Almost 20% cells even survived in very high doses (upto 10%) of DMSO (Graph 5).

Immunocytochemistry confirms pluripotency in NIH3T3 cells

To determine whether NIH3T3 cells express pluripotent or multipotent markers, cells were cultured on glass coverslips and immunostained after 24 h for ESC (ONS) and various other markers associated with stemness and progenitor state. We observed intense positive staining in both mBMSC and NIH3T3 for Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2, which was similar to mESC (Fig. 4a). Moreover, we also found that NIH3T3 cells were positive for Nestin, Vimentin, Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA), Ki-67, Fibronectin, E-cadherin, and pancreatic duodenal homeobox gene-1 (PDX-1) (Fig. 4b, c). Nestin and Vimentin are markers of neural and MSC, respectively, whereas Fibronectin and SMA confirm MSC-like features. In addition, we noticed that NIH3T3 cells were strongly positive for PDX-1, which is not only a pancreatic progenitor marker but is also expressed by pluripotent stem cells [2].

FIG. 4.

Immunocytochemistry of mESC, mBMSC, and NIH3T3: (a) represents pluripotency marker staining OCT3/4 (red), Nanog (green), and Sox-2 (yellow) in mESC, mBMSC, and NIH3T3 cells, respectively. (b, c) represents comparative immunophenotyping of other stem cell markers in mBMSCs and NIH3T3 cells. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Gene expression analysis indicates pluripotent nature of NIH3T3 cells

Subsequently, when we found NIH3T3 cells to be positive for stemness markers by immunocytochemistry, we tested them for the presence of these pluripotent, multipotent, and differentiation markers at transcript (mRNA) levels by semiquantative reverse transcriptase and qRT-PCR in NIH3T3 cells procured from second-source Zydus Pharmaceuticals, Ahmedabad, India. Expression profiles of all stem cell markers such as Oct3/4, Nanog, Sox-2, Nestin, Vimentin, SMA, PDX-1, and Neurogenin-3 (Ngn-3) were carried out. mBMSC at P10 were found to be positive for all Oct3/4, Nanog, Sox-2 (by q-PCR), Nestin, Vimentin, SMA, and PDX-1, and Ngn-3 (by RT-PCR) (Fig. 5). These marker profiles, determined by q-PCR, clearly demonstrate the pluripotency of mBMSC as Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2 expression were up-regulated in them. Expression profiles of the same markers were screened in NIH3T3 cells of P15. The cells were found to be positive for Oct3/4, Nanog, Sox-2, Vimentin, SMA, Nestin, PDX-1, and Ngn-3 by RT-PCR; whereas contradictorily, down-regulation of Oct3/4, Nanog (100 times), and Sox-2 (1,000 times) was also observed in these cells by q-PCR when compared with mBMSC expression (Fig. 6). To further validate and confirm that NIH3T3 cells retain pluripotent nature, we compared NIH3T3 with mESC by RT-PCR; interestingly, we found these cells to express all three ONS genes, which was similar to mESC. Further, NIH3T3 cells were also found to express ABCG2, which is an important transporter molecule in ESCs. We also examined the expression of tri-lineage germ layer markers such as β-III tubulin, Otx-2 for Neuroectodermal layer, GATA-2, Brachyury (T) for Mesodermal layer, and GATA-4 and Pdx-1 for Endodermal layer in NIH3T3 aggregated clusters, which was similar to EBs generated from mESC (Fig. 5a).

FIG. 5.

Gene expression analysis of mESC, mBMSC, and NIH3T3: (a) represents comparative gene expression profile of pluripotency markers and trigerminal layer markers in mESC and NIH3T3 cells. (b) Represents mRNA expression of other stem cell genes in mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells.

FIG. 6.

Comparative q-PCR Plot for gene expression of NIH3T3 and mBMSC: Figure represents a comparative study of gene expression profile of 3 crucial stem cell markers—Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2, in NIH3T3 and mBMSC by real-time PCR. Results are the mean of triplicates performed independently in two sets of experiments using cells at a different passage number. q-PCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Flow cytometry analysis supports pluripotent nature of NIH3T3 cells

FACS analysis of ONS markers in both mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells was carried out. We clearly observed that both mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells showed ONS positivity. On comparing the percentage population of mBMSC, we found that 7.91% cells were positive for Oct-3/4, 70.87% cells for Nanog, and 75.37% cells for Sox-2 (Fig. 7). Likewise, in the case of NIH3T3, 6.13% cells were positive for Oct-3/4, 70% cells for Nanog, and 7.96% cells for Sox-2 (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

FACS histograms of ONS markers in mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells: figure represents comparative histograms of pluripotency marker profile from mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells. ONS, Oct-3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2.

Western blot profile validates pluripotent stem cell-like nature of NIH3T3 cells

For confirming the presence of ONS genes at the protein level, western blot was carried out with the cell lysate of mBMSC and NIH3T3. As expected, both the cell types from two different passage numbers (P10 and P12 in mBMSC and P31 and P33 in NIH3T3; see Fig. 8) were positive for Vimentin, Fibronectin, SMA, Ki-67, PDX-1, and Ngn-3. Both mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells showed high expression levels of both precursor and mature isoforms of Fibronectin protein, which were 170 and 90 kDa, respectively. The level of SMA expression in NIH3T3, however, was a little lower than that in mBMSC; whereas that of Ki67 isoforms of 395 and 365 kDa was higher in NIH3T3 cells. Further, the expression of Nestin was seen in NIH3T3 cells only but not in mBMSC. In fact, the expression levels of Vimentin, PDX-1, and Ngn-3 were also very high in NIH3T3 compared with those in mBMSC (Fig. 8). More interestingly, we further found that mBMSC cells demonstrated increased protein expression of ONS markers from P10 to P12; nonetheless, NIH3T3 cells showed bands for Oct-3/4 of 34 kDa, Nanog of 42 kDa, and Sox-2 of 38 kDa at both P31 and P33. We also checked expression of ONS in GFP-labeled NIH3T3 cells before teratoma formation during in vivo studies to ensure pluripotency. NIH3T3-eGFP cells as per our expectation showed ONS protein bands even after GFP labeling (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Western blotting profile of NIH3T3 and mBMSC: figure represents comparative protein expression profile of pluripotency and other stem cell markers from mBMSC (P10 and P12) and NIH3T3 (P31 and P33). Figure also represents ONS expression in NIH3T3-eGFP cells post-transfection at P5.

In vivo teratoma formation reconfirms pluripotency in NIH3T3 cells

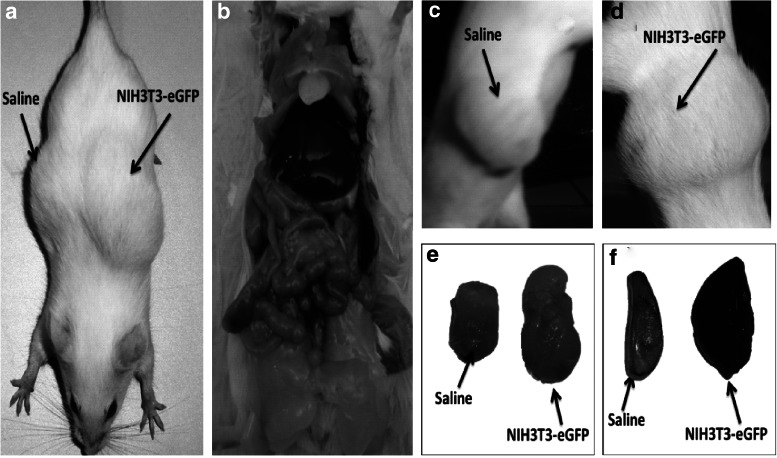

To further validate the phenotypic properties of NIH3T3 cells in terms of pluripotency, an in vivo experiment for teratoma formation in Balb/c mice was carried out. NIH3T3-eGFP cells in a small aliquot of medium with 1.5% warm agarose plugs were transplanted subcutaneously on the left side of ten Balb/c mice [28–30,36,37]. The right side of the same animals was used for control or placebo that is, only agarose plugs were injected at that site. After 15 days of transplantation, mice were sacrificed after teratoma formation from NIH3T3-eGFP cells had been observed in these animals. All of the 10 mice developed evident teratomas (left side) wherein skin bulges were bigger in size than those of agarose plugs alone (right side) (Fig. 9). In addition, we noted that teratomas formed by NIH3T3-eGFP cells injected in agarose plugs were significantly larger (average weight of 0.999±0.1 g and volume 2.70±0.48 mm3) than those formed by agarose plugs alone (average weight 0.70±0.03 g and volume 1.5−0.16 mm3) (Fig. 10). GFP imaging of teratoma sections demonstrated that a major mass of tumor plugs was mainly derived from NIH3T3-eGFP cells only and not from host dermal cells (Fig. 11). Immunohistochemistry of tri-lineage markers clearly depicted the presence of pluripotency markers ONS in developed tumor tissues. Representative regions of slides showed colabeling of Oct-3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2 with GFP staining (Fig. 13). Histological studies confirmed the in vivo functionality and representation of tri-germinal layers in developed teratomas (Fig. 12; see Supplementary Fig. S2 showing Alizarin red and Oil O Red staining in excised teratoma sections after 15 days. Fig. S1 showed staining for oesteo and adipocytic differentiation in vitro). The infused cells were found to be confined to the transplanted areas only, as all other organs in the alimentary canal were normal and no significant metastasis was observed. Since the cells were encapsulated in agarose and transplanted subcutaneously beneath the forearms and not directly in vasculature, hence, the chances of spreading were minimal to begin with. Apart from this, in order to effectively validate the signatures of all three germ layers in the excised teratomas, we confirmed the markers of ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm using immunohistochemistry with GFP colabeling. NIH3T3-eGFP teratoma slices stained positive for Nestin, neurofilament markers for ectodermal germ layer, CD44 specific marker for mesodermal cell types, and PDX-1 for endodermal germ cells (Fig. 14).

FIG. 9.

In vivo study for teratoma formation in Balb/c mice: (a) shows NIH3T3-eGFP produced teratomas in Balb/c mice on the left side of mice, while saline showed no outgrowth on the right side of the body. (b) Represents no other organ affected by teratoma as transplanted cells did not metastasize. (c) and (d) Shows subcutaneous teratoma bulging on left and right peritoneum of mice respectively. (e) Indicates difference in the size of the teratomas between transplanted cells in saline and those in agarose plugs. (f) Represents ALP staining of cells transplanted in agarose plug after 15 day teratoma formation.

FIG. 10.

Comparative graph for weight and volume of NIH3T3-eGFP induced teratoma and agarose plug alone after 15 days. Results are expressed as mean±SEM with n=6–10 animals. * and ** represents P<0.01 and P<0.001 versus control plugs (Saline), respectively.

FIG. 11.

Histological images of teratoma: figure represents histological and GFP fluorescence in panel (a) agarose plug alone and (b) NIH3T3-GFP-developed teratoma. Teratoma sections of agarose plugs with NIH3T3-eGFP cells showing GFP fluorescence with representatives of three germinal layers in teratoma sections. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

FIG. 13.

Immunohistochemistry of NIH3T3-eGFP teratoma sections: figure represents pluripotency markers OCT-3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2 staining in NIH3T3-eGFP teratoma sections with GFP colocalization. Panel represents ONS staining in red, GFP staining in green, and DAPI nuclear staining in blue with merged image. DAPI, 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

FIG. 12.

Histological images of teratoma: figure represents histological representatives for trigerminal lineages, panel (a) ectoderm (b) endoderm (c) mesoderm (skeleton muscles), and (d) mesoderm (adipose tissue). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

FIG. 14.

Immunohistochemistry of NIH3T3-eGFP teratoma sections: figure shows ectodermal; Nestin (red) expression in a few GFP (green) positive cells representing neuroectodermal cell lineage, mesoderm; CD34 (red) positive nuclei marker of chondrocyte cells, and endoderm; PDX-1 positive (red) nuclei depicting presence of pancreatic endodermal layer. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Discussion

NIH3T3 cells, till 2005, were not known to possess stemness properties. Recent studies have shown stemness in NIH3T3, as the cells are capable of differentiating into various cell types such as neural cells, oesteocytes, and adipocytes, including insulin-producing beta cells [1,19–21,24–26].

The present study is an attempt to demonstrate whether pluripotency and stemness is associated with basal levels of ONS genes. Efforts were made to unravel these facts by demonstrating characteristic features of NIH3T3 in terms of stemness by undertaking a comparative analysis of NIH3T3 with mBMSC employing cellular and molecular techniques. Morphologically, NIH3T3 showed more or less similar shape-like fibroblastic mBMSC with the ability to survive in culture conditions for numerous passages. We also found that NIH3T3 became progressively hyperplastic and that they get interlaced with one another with an increase in the number of days in culture. Multiple layers of cells are produced, as the cells' growth is not inhibited by contact inhibition as described earlier [14]. A histological observation also supported the proliferative rate and plasticity of NIH3T3 cells. High chromatin content and frequent appearance of dividing nuclei indicated progenitor-like features, which are in accordance with earlier studies done with pluripotent stem cells [1,5,38–40].

ISSCR guidelines suggest ALP activity as one of the critical criteria of pluripotency, which has also been emphasized by Riekstina et al. [2]. On these grounds, we demonstrated that NIH3T3 cells formed spheroid bodies that stained positive for ALP staining. The purple color in NIH3T3 spheroids indicated a characteristic feature of EBs derived from pluripotent ESCs, reinforcing their enhanced stemness. These findings are in concurrence with those of Li and Riekstina et al. [2,5].

Molecular and immunological characterization is important to investigate the presence of stem cell-like markers at both mRNA and protein levels. To achieve this, we characterized NIH3T3 cells from all the three different sources as mentioned earlier at gene and protein levels by RT-PCR, q-PCR, immunocytochemistry, flow cytometery, and western blotting. Based on the immunocytochemistry results, we conclude that NIH3T3 cells obtained from the first source, that is, NCCS Pune, India at P4, showed the presence of all characteristic markers which are relevant to pluripotency. They express ESC markers such as Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2. NIH3T3 cells were highly positive for Nestin, a neuroendocrine filament protein, expressed in pluripotent neural stem cells [41,42]. It is also reported that Nestin is widely expressed in pluripotent stem cells from various other tissues such as the ear [5], dermal fibroblast [31], and pancreatic lineage cells [43]. NIH3T3 cells were also found to be positive for mesenchymal lineage markers such as Vimentin, SMA, and Fibronectin, confirming their mesenchymal or multipotent status. Various pluripotent or multipotent MSCs are known to express Vimentin, Fibronectin [1,44], and SMA [7]. PDX-1, a pancreatic progenitor marker present in pluripotent MSC [2], was also found to be expressed by NIH3T3, indicating their predisposition to give rise to definitive endoderm. Pluripotent stem cells are also known to have high E-cadherin content [1], which represents higher self-renewal capacity and undifferentiated status. When we examined mBMSC and NIH3T3 cells, both strongly expressed E-cadherin, a finding in good agreement with that of Conrad and group [1]. These finding clearly suggested that NIH3T3 cells harbor pluripotent characteristics.

We further tested NIH3T3 stemness at the molecular level at P15 obtained from the second source, that is, Zydus Pharmaceuticals. The idea was to demonstrate that the results and observations we had recorded so far in an early passage of NIH3T3 by immunocytochemistry held true in cells of higher passage numbers obtained from another source. The presence of OCT-3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2 represented an ESC-like state as reported by Yamanaka and group [3]. Nanog is known to be responsible for self-renewal, pluripotency, and for maintaining an undifferentiated state of cells [45]. As per our observations evident by RT-PCR, NIH3T3 cells express Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2 albeit at slightly lower levels, thus indicating their pluripotent nature. Further, NIH3T3 cells also expressed ABCG2, an important transporter molecule that is abundant in ESCs. In order to reconfirm our semi-quantitative PCR data, we decided to quantify the levels of the genes by a more sensitive technique such as qRT-PCR. Results showed that NIH3T3 exhibited a 100-fold lesser level of Oct3/4 and Nanog expression, while that of Sox-2 was 1,000 fold less than that in mBMSC. We hypothesize that NIH3T3 cells sustain their pluripotency, through sub-basal levels of Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2 unlike ESCs. However, the presence of ONS can perhaps explain the differentiation potential of NIH3T3 cells into neural cells, oesteocytes, and adipocytes as reported by Deng group [21,23] and pancreatic islets by Gupta et al. [26]. In one of the recent reports, we also demonstrated successful differentiation of NIH3T3 cells into islet-like cell clusters [26], further validating the pluripotent nature of these cells. Even further, flow cytometery and western blotting confirming the presence of ONS proteins in NIH3T3 cells similar to mBMSC provide additional support to the hypothesis and authenticate the fact that NIH3T3 may represent a connecting link to ESCs with regard to pluripotency.

Pluripotent cells have the ability to differentiate into cell types of all three germinal layers, namely ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm, under suitable culture conditions. In vitro pluripotency of cells can be assessed by their ability to form three dimensional structures called EBs or aggregates or spheroids; on the other hand, in vivo pluripotency can be characterized by the ability to form putative tumours when implanted into immunocompromised animals [37]. Noncancerous benign tumors formed by ESCs are called teratomas [36,37]. Our studies demonstrated interesting results in terms of spheroid formation in vitro and teratoma formation in vivo with NIH3T3 cells. GFP-expressing NIH3T3 cells, when engrafted with agarose plugs without any growth factors, showed high incidence of teratoma formation in immune compromised mice such as Balb/c. NIH3T3eGFP cells not only demonstrated the ability to proliferate under in vivo conditions to form noncancerous cell mass, but also stimulated angiogenesis, which was evident by new blood vessel formation within 15 days. The behavior of NIH3T3 cells in vivo was fairly identical to ESC-induced teratoma formation. An immunological confirmation of three lineage markers such as Nestin, CD44, and PDX-1 for ecto-, meso-, and endoderm layers further verified in vivo pluripotency of NIH3T3 cells. All these results demonstrate the pluripotent nature of NIH3T3 cells representing a connecting link between mBMSC and mESC.

Conclusions

Several lines of evidence in our study lend credence for the pluripotent nature of NIH3T3 cells. The most striking evidence that provided functional confirmation for their pluripotency were strong ALP staining, basal Nanog expression, and high teratoma-forming capacity of these cells in mice without any growth supplements. Interestingly, the acquisition of pluripotency in NIH3T3 cells was concurrent with the lower levels of Nanog expression in comparison with mESC rather than complete silencing of the gene as witnessed in mBMSC cells. Their potential to differentiate into neurons and insulin-producing cells furnished functional evidence of their pluripotentiality. Thus, our findings demonstrate that NIH3T3 cells have pluripotent characteristics and can be differentiated into cells of all three germ lines, which suggest that basal level of ONS gene expression can also lead to pluripotent stem cell-like feature, thereby conferring pluripotency and tri-lineage differentiation potential. These promising findings offer a new hope to look for pluripotent/multipotent stem cells from different human tissue-specific cell types already in culture that could potentially be used in clinics for autologous cell therapy in degenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Authors would like to acknowledge Department of Biotechnology, government of India, New Delhi for funding the project (grant no:- BT/TR-7721/MED/14/1071/2006) and providing financial grant for establishing central instrumental facility for confocal microscopy, FACS etc. at Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda, India under DBT-MSUB-ILSPARE programme (grant no:- BT/PR14551/INF/22/122/2010). We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Salil Vaniawala, gene lab, Surat, Gujarat, India for helping us in karyotyping analysis.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Conrad S. Renninger M. Hennenlotter J. Wiesner T. Just L. Bonin M. Aicher W. Buhring HJ. Mattheus U, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult human testis. Nature. 2008;456:344–349. doi: 10.1038/nature07404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riekstina U. Cakstina I. Parfejevs V. Hoogduijn M. Jankovskis G. Muiznieks I. Muceniece R. Ancans J. Embryonic stem cell marker expression pattern in human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, heart and dermis. Stem Cell Rev. 2009;5:378–386. doi: 10.1007/s12015-009-9094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyun I. Lindvall O. Ahrlund-Richter L. Cattaneo E. Cavazzana-Calvo M. Cossu G. De Luca M. Fox IJ. Gerstle C, et al. New ISSCR guidelines underscore major principles for responsible translational stem cell research. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:607–609. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H. Liu H. Heller S. Pluripotent stem cells from the adult mouse inner ear. Nat Med. 2003;9:1293–1299. doi: 10.1038/nm925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner RL. Stem cells: potency, plasticity and public perception. J Anat. 2002;200:277–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medici D. Shore EM. Lounev VY. Kaplan FS. Kalluri R. Olsen BR. Conversion of vascular endothelial cells into multipotent stem-like cells. Nat Med. 2010;16:1400–1406. doi: 10.1038/nm.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phinney DG. Prockop DJ. Concise review: mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair—current views. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2896–2902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang Y. Jahagirdar BN. Reinhardt RL. Schwartz RE. Keene CD. Ortiz-Gonzalez XR. Reyes M. Lenvik T. Lund T, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu H. Guo ZK. Jiang XX. Li H. Wang XY. Yao HY. Zhang Y. Mao N. A protocol for isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse compact bone. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:550–560. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mezey E. Key S. Vogelsang G. Szalayova I. Lange GD. Crain B. Transplanted bone marrow generates new neurons in human brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1364–1369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Ippolito G. Diabira S. Howard GA. Menei P. Roos BA. Schiller PC. Marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible (MIAMI) cells, a unique population of postnatal young and old human cells with extensive expansion and differentiation potential. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2971–2981. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z. Oron E. Nelson B. Razis S. Ivanova N. Distinct lineage specification roles for NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:440–454. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todaro GJ. Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu SF. Chen TM. Chen YH. Apoptosis and necrosis are involved in the toxicity of Sauropus androgynus in an in vitro study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:537–547. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(07)60004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patki PS. Evaluation of in vitro toxicity of Rumalaya liniment using mouse embryonic fibroblasts and human keratinocytes. Int J Green Pharm. 2011;5:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Groene EM. Seinen W. Horbach GJ. A NIH/3T3 cell line stably expressing human cytochrome P450-3A4 used in combination with a lacZ' shuttle vector to study mutagenicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;293:47–53. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(95)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhar S. Mali V. Bodhankar S. Shiras A. Prasad BL. Pokharkar V. Biocompatible gellan gum-reduced gold nanoparticles: cellular uptake and subacute oral toxicity studies. J Appl Toxicol. 2010;31:411–420. doi: 10.1002/jat.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russo S. Tomatis D. Collo G. Tarone G. Tato F. Myogenic conversion of NIH3T3 cells by exogenous MyoD family members: dissociation of terminal differentiation from myotube formation. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 6):691–700. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.6.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuo X. Li G. Luo T. Li J. Liu Y. Luo M. Differentiation of NIH3T3 fibroblasts into adipocytes induced by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma 2 expression. Chin Med J (Engl) 2001;114:916–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z. Sugano E. Isago H. Hiroi T. Tamai M. Tomita H. Differentiation of neuronal cells from NIH/3T3 fibroblasts under defined conditions. Dev Growth Differ. 2011;53:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2010.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piestun D. Kochupurakkal BS. Jacob-Hirsch J. Zeligson S. Koudritsky M. Domany E. Amariglio N. Rechavi G. Givol D. Nanog transforms NIH3T3 cells and targets cell-type restricted genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo WC. Hsu CH. Wu AT. Yang LY. Chen WH. Chiu WT. Lai WF. Wu CH. Gelovani JG. Deng WP. A novel cell-based therapy for contusion spinal cord injury using GDNF-delivering NIH3T3 cells with dual reporter genes monitored by molecular imaging. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1512–1519. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo WC. Chiou JF. Gelovani JG. Cheong ML. Lee CM. Liu HY. Wu CH. Wang MF. Lin CT. Deng WP. Transplantation of embryonic fibroblasts treated with platelet-rich plasma induces osteogenesis in SAMP8 mice monitored by molecular imaging. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:765–773. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdallah BM. Osteoblast differentiation of Nih3t3 fibroblasts is associated with changes in the Igf-I/Igfbp expression pattern. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2006;11:461–474. doi: 10.2478/s11658-006-0038-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta S. Dadheech N. Singh A. Soni S. Ramesh RB. Enicostemma littorale: a noval therapeutic target for islet neogenesis. Int J Integr Biol. 2010;9:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsiao FS. Cheng CC. Peng SY. Huang HY. Lian WS. Jan ML. Fang YT. Cheng EC. Lee KH, et al. Isolation of therapeutically functional mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells within 3 h by an effective single-step plastic-adherent method. Cell Prolif. 2010;43:235–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen SS. Fitzgerald W. Zimmerberg J. Kleinman HK. Margolis L. Cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions regulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2007;25:553–561. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Awad HA. Wickham MQ. Leddy HA. Gimble JM. Guilak F. Chondrogenic differentiation of adipose-derived adult stem cells in agarose, alginate, and gelatin scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3211–3222. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ando T. Yamazoe H. Moriyasu K. Ueda Y. Iwata H. Induction of dopamine-releasing cells from primate embryonic stem cells enclosed in agarose microcapsules. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2539–2547. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byrne JA. Nguyen HN. Reijo Pera RA. Enhanced generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from a subpopulation of human fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugano E. Tomita H. Ishiguro S. Abe T. Tamai M. Establishment of effective methods for transducing genes into iris pigment epithelial cells by using adeno-associated virus type 2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3341–3348. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das AV. Mallya KB. Zhao X. Ahmad F. Bhattacharya S. Thoreson WB. Hegde GV. Ahmad I. Neural stem cell properties of Muller glia in the mammalian retina: regulation by Notch and Wnt signaling. Dev Biol. 2006;299:283–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liseth K. Abrahamsen JF. Bjorsvik S. Grottebo K. Bruserud O. The viability of cryopreserved PBPC depends on the DMSO concentration and the concentration of nucleated cells in the graft. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:328–333. doi: 10.1080/14653240500238251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi W. Ding D. Salvi RJ. Cytotoxic effects of dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) on cochlear organotypic cultures. Hear Res. 2008;236:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blum B. Bar-Nur O. Golan-Lev T. Benvenisty N. The anti-apoptotic gene survivin contributes to teratoma formation by human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:281–287. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prokhorova TA. Harkness LM. Frandsen U. Ditzel N. Schroder HD. Burns JS. Kassem M. Teratoma formation by human embryonic stem cells is site dependent and enhanced by the presence of Matrigel. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:47–54. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowry WE. Richter L. Yachechko R. Pyle AD. Tchieu J. Sridharan R. Clark AT. Plath K. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from dermal fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2883–2888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711983105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanatsu-Shinohara M. Inoue K. Lee J. Yoshimoto M. Ogonuki N. Miki H. Baba S. Kato T. Kazuki Y, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from neonatal mouse testis. Cell. 2004;119:1001–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reiisi S. Esmaeili F. Shirazi A. Isolation, culture and identification of epidermal stem cells from newborn mouse skin. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2010;46:54–59. doi: 10.1007/s11626-009-9245-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lendahl U. Zimmerman LB. RD M. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell. 1990;60:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dahlstrand J. Zimmerman LB. McKay RD. Lendahl U. Characterization of the human nestin gene reveals a close evolutionary relationship to neurofilaments. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:585–597. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L. Hong TP. Hu J. Liu Y-N. Wu Y-H. Li L-S. Nestin-positive progenitor cells isolated from human fetal pancreas have phenotypic markers identical to mesenchymal stem cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2906–2911. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i19.2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawase Y. Yanagi Y. Takato T. Fujimoto M. Okochi H. Characterization of multipotent adult stem cells from the skin: transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) facilitates cell growth. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei L. Dou L. Wang H. Knock-down Nanog gene expression by siRNA affects the differentiation of cardiomyocytes in P19 cell. Cell Res. 2008;18:36. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.