Abstract

Objective To characterise the percentage of available outcome data being presented in reports of randomised clinical trials with continuous outcome measures, thereby determining the potential for incomplete reporting bias.

Design Descriptive cross sectional study.

Data sources A random sample of 200 randomised trials from issues of 20 medical journals in a variety of specialties during 2007–09.

Main outcome measures For each paper’s best reported primary outcome, we calculated the fraction of data reported using explicit scoring rules. For example, a two arm trial with 100 patients per limb that reported 2 sample sizes, 2 means, and 2 standard deviations reported 6/200 data elements (1.5%), but if that paper included a scatterplot with 200 points it would score 200/200 (100%). We also assessed compliance with 2001 CONSORT items about the reporting of results.

Results The median percentage of data reported for the best reported continuous outcome was 9% (interquartile range 3–26%) but only 3.5% (3–7%) when we adjusted studies to 100 patients per arm to control for varying study size; 17% of articles showed 100% of the data. Tables were the predominant means of presenting the most data (59% of articles), but papers that used figures reported a higher proportion of data. There was substantial heterogeneity among journals with respect to our primary outcome and CONSORT compliance.

Limitations We studied continuous outcomes of randomised trials in higher impact journals. Results may not apply to categorical outcomes, other study designs, or other journals.

Conclusions Trialists present only a small fraction of available data. This paucity of data may increase the potential for incomplete reporting bias, a failure to present all relevant information about a study’s findings.

Introduction

Bench research produces physical evidence, such as an electrophoresis gel, that can be photographed and published for examination by members of the scientific community. Clinical research yields no such physical evidence, just a complex array of values that cannot be presented in total in print. A bench researcher who presents only the section of the electrophoresis gel that serves his thesis will be accused of incomplete reporting or abject fraud.1 Yet, by necessity, authors of clinical studies routinely select which sections of their dataset to present; they decide which independent and dependent variables are worthy of mention, how each is to be depicted, and whether each variable will be presented stratified on other variables. This process of selecting what to present is not trivial; authors must balance the contradictory principles of comprehensiveness and brevity.

Selective reporting of data can occur on three levels. First, investigators may choose to leave unappealing data unpublished, a phenomenon known as publication bias.2 3 Second, investigators may publish trial results, but report only those outcomes whose results support their desired conclusion, known as outcome reporting bias.4 5 6 7 Finally, authors may selectively report only those descriptive and analytical statistics about each outcome that favour their argument, which we call incomplete reporting bias. For example, authors might report a statistically significant difference between group means but fail to report that group medians were similar. Depicting the distributions for each group would eliminate this ambiguity. Similarly, authors may fail to depict relationships that would help readers understand whether observed results could be due to confounding. The depiction of distributions stratified on potential confounding variables can help readers make this evaluation.

Trial registration, now required by most major journals, is one attempt to address selective reporting at the first two levels.8 Editors at BMJ and Annals of Internal Medicine have suggested that the posting of clinical databases to the web is the best way to address the third by decreasing the likelihood of selective, biased reporting within a paper.9 10 11 While the debate regarding “how much data is enough” is contentious, understanding current practice is an important step in developing plans to address this issue.

To that end we sought to describe how much data are being presented in journal articles and how they are being presented. We chose to study randomised trials with continuous outcomes because randomised trials are the most important form of clinical evidence and because options for depicting continuous data are better developed than those for categorical data.

Methods

Article selection

Based on our experience with similar projects, we decided that 10 articles per journal from 20 high impact journals would provide an adequately stable picture of the state of the literature. Using the 2008 Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) rankings and before looking at tables of contents or articles, we chose the top six general medicine journals and first and fourth ranked journals in each of seven medical specialties to provide a wide cross section of medical and surgical disciplines. We included emergency medicine as one of the specialties, knowing that this would ensure that the two journals we work with closely, Annals of Emergency Medicine (DLS) and BMJ (DGA), would be included in the sample. Our sole inclusion criterion was that each article be a randomised trial with a continuous primary outcome, defined as a variable that could take on five or more distinct values. There were no exclusion criteria.

We used the 2006 issues of our journal pool to determine that more than two thirds of randomised trials contained a continuous primary outcome, and, based on this, we sought to identify 15 randomised trials from each journal to ensure we would have 10 eligible trials. One author (DFS) reviewed all 2007 and 2008 tables of contents to identify all randomised trials, extending the search through to June 2009 if necessary to get 15 trials. If there were still insufficient articles, we moved to the next lower journal in the ISI rankings for that specialty. For each journal, we randomly ordered the potentially eligible articles using the random number feature in Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and selected the first 10 articles that had at least one continuous primary outcome.

Outcome measure

Our primary outcome is the fraction of available data reported for the primary outcome that was most completely reported in each eligible article. The numerator of this fraction, the number of data points presented, is conceptually straightforward, though some operational rules are required to achieve consistent counts. We based counting rules on methods we developed for the determination of data density in scientific figures and tables12 13 (see appendix 1 on bmj.com for details). For each article, we noted whether the majority of values counted in the numerator were reported in text, table, or figure. The numerator was the sum of all unique values presented across the three formats.

The fraction’s denominator is dependent on one’s vision of how much data ought be presented, a topic for which there is no consensus. We defined a series of denominators of differing stringency, the most lenient of which reflects our belief that, at minimum, a trial with one or more continuous primary outcomes should present each subject’s value for at least one outcome. More stringent denominators expect complete reporting of all author-defined continuous primary outcomes, outcome data reflective of the study design (such as the paired data that occur when data are collected and analysed at baseline and at a subsequent time point should be depicted as such), and outcomes stratified on important covariates. We found that reporting was poor even for the most lenient denominator and, for simplicity, report only on this outcome in the main paper. Results for more stringent outcomes can be found in the supplementary figures.

We also noted each study’s compliance with the relevant elements of the 2001 CONSORT statement as an alternative metric of the completeness of data presentation.14 15 The 2001 CONSORT statement suggests that authors specify a primary outcome measure (item No 6) and indicate the number of participants per intervention group (items 13 and 16) and the effect size and its precision (item 17).14 It defines “primary outcome measure” as “the prespecified outcome of greatest importance ... the one used in the sample size calculation” and notes that “some trials may have more than one primary outcome. Having more than one or two outcomes, however, incurs the problems of interpretation associated with multiplicity of analyses and is not recommended.”15

Post hoc, we decided to examine journal records for the 20 papers that were published in BMJ and Annals of Emergency Medicine, the two journals in the sample with which we have affiliations, to try to understand what factors may have affected data presentation. For Annals of Emergency Medicine, we had access to all versions of the manuscript and all reviews and correspondence, and determined whether graphics changed from initial submission to final publication and whether changes were prompted by reviewer comments. For BMJ we had access to the critiques of reviewers and editors but not the original submission and tallied the percentage of words devoted to comments about methodology and to comments specifically about the reporting of results.

Data abstraction

All articles were obtained electronically as .pdf files of the full, final, online version from the journal websites by one author (DFS), who archived them using Bookends software, version 10.5 (Sonny Software, Chevy Chase, MD, USA). Care was taken to review each article for any reference to additional online information such as supplementary text, tables, figures, print, audio, or video appendices, and to print material unavailable online, and to obtain all material that might provide additional information about the study outcomes. We used Skim (version 1.2.1, open source) to annotate the articles, highlighting the relevant text (description of primary outcomes, discussion of study design, and identification of covariates, data, and figure types) in standardised colours (see appendix 2 on bmj.com for an example). We identified all portrayals of outcome data in text, tables, and figures. We then reviewed highlighted text and transferred relevant information onto standardised data forms in Oracle OpenOffice.org (version 3.0, Oracle, Redwood Shores, CA, USA). We (DLS, DFS) performed an interrater reliability assessment on 10 randomly selected 2006 articles by independently scoring each article. We achieved 100% agreement for our primary outcome, the proportion of data presented based on the lenient rule. One author (DFS) performed the remaining abstractions, checking with another (DLS) when he had questions.

Data management and analysis

Data were transferred to Stata 12, which we used for data cleaning, analysis, and graphics creation. Our intent was descriptive. We used graphics to simultaneously present the raw data and summary statistics.

Results

Many journals had insufficient articles; we replaced them with journals ranked second (1), fifth (2), seventh (3), and ninth (2) (see extra table A in appendix 3 on bmj.com for a list of journals and their rankings). The average number of participants in the 200 studies was 331 (median 118, range 12–13 965). Ten per cent of studies had more than 250 participants per arm, 65% less than 100, and 49% had less than 50 (see extra table B and fig A in appendix 3). Individual journals ranged from a median of 46 to 557 participants per study (mean 60 to 2132).

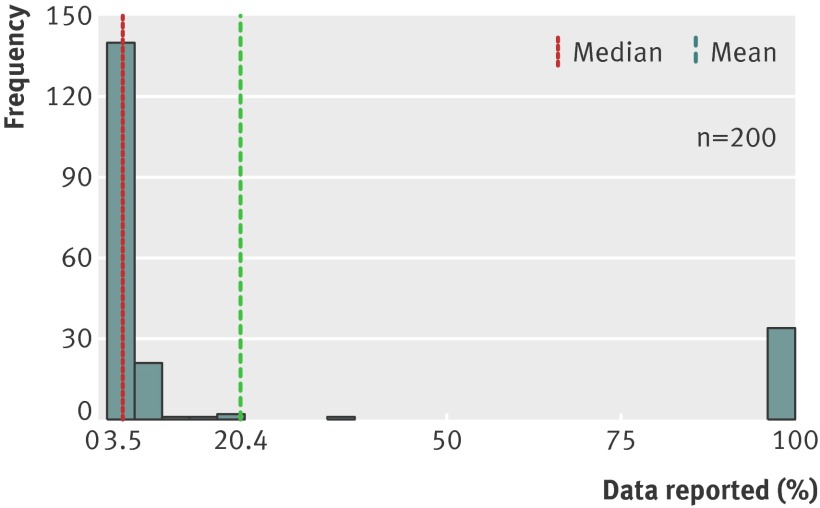

Authors reported a median 9% of data for the best reported outcome (interquartile range 3–26%) (extra fig B in appendix 3). However, there was an unintended artefactual relationship between sample size and our reporting metric. A paper that presents two means, two standard deviations, and two sample sizes as the sole representation of a two arm randomised controlled trial with 100 patients in each arm scores 6/200=1.5%; but a trial with 10 patients per arm that presents the same six values, now out of a possible 20 data points, scores 6/20=30% despite the fact that reporting is no better. To eliminate this problem we also scored each trial as if it had 100 participants per arm with the exception that any arm where all data were presented was scored at 100% regardless of the arm’s actual number of subjects. With this adjustment, median reporting was 3.5% (interquartile range 3.2–6.5%) and mean reporting was 20.4%, both lower than the unadjusted estimates (fig 1). Furthermore, that most studies present either a tiny fraction of the data (mean, variance measure, and sample size for each arm) or all of the data becomes evident. The median per cent reported for more stringent measures ranged from 0.2% to 3% (extra figs C and D in appendix 3).

Fig 1 Histogram of percentage of data reported for best reported continuous outcome, based on 100 subjects per trial arm. We set the sample size (N) for each study limb so that study size did not confound our reporting metric. This histogram, in contrast with the histogram based on actual limb sizes (extra fig B in appendix 3 on bmj.com), shows that almost all papers either reported all of their data for the best reported primary outcome or just Ns, means, and confidence intervals. (See extra figs C and D in appendix 3 for details)

We next examined how the mode of presentation related to the comprehensiveness of data presentation. There were 34 (17%) papers that achieved a 100% score by providing subject-level data for the best reported outcome, including: 14 scatterplots, six Kaplan-Meier plots, five plots of each individual’s change from baseline, four histograms, one line graph, and five tables. Of note, two of the five tables achieved full marks by having one line per patient in studies that had a total of 17 and 40 patients. The other three tables were from the 12 papers that had a “continuous” primary outcome measure that had between five and nine possible values and presented how many patients achieved each value. While tables were the most common method of data presentation (117, 59%), figures (74, 37%) presented a larger fraction of the data regardless of sample size (extra fig E in appendix 3); only figures that showed individual observations or distributions (such as scatterplots, histograms, and survival curves) outperformed tables (extra fig F).

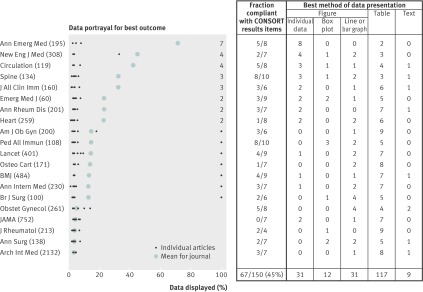

We next examined papers stratified by journal (fig 2, extra fig G in appendix 3). There is evident heterogeneity, with means for the best outcome reported ranging from 3% to 72% (medians 3–100%). In 40% of journals there was not a single figure depicting the distribution of an outcome. Annals of Emergency Medicine had seven papers that had 100% reporting of the primary outcome and two that did so for a secondary outcome. In all nine cases the original manuscript did not include a figure that garnered full marks. The published figures were added at the request of a methodology editor (5), a decision editor (1), or the tables and figures editor (3). At BMJ one paper had full reporting, and the correspondence makes it clear that this figure was added at the request of the methodology editor. Critiques of remaining papers at BMJ had no evidence of requests for more comprehensive data presentation. The BMJ critiques had 30% of words devoted to comments on methodology, 21% of which (6% of all words) were related to the presentation of results.

Fig 2 The plot shows the show the percentage of data reported for the best reported outcome for each article and the mean for each journal. (Numbers on the far right of the figure indicate the number of articles that achieved 100% reporting for that journal. Numbers in parentheses represent the mean number of patients in that journal’s papers.) The table shows the method used to present the data by the 10 articles in each journal and the number of eligible articles that were CONSORT compliant (components include description of participant flow through each stage, baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of each group, number of participants in each analysis, and, for each primary outcome, a summary result for each group as well as the estimated effect size and its precision14). The CONSORT assessment was performed only on studies with 2 parallel arms, hence the denominator is <10 at times

With respect to the CONSORT requirements, only 148 (74%) of papers explicitly identified primary outcome(s), and authors and editors are apparently not terribly bothered by the oxymoronic nature of multiple “primary” outcomes, as articles that identified one or more primary outcomes included a median of three (interquartile range 2–6) (mean 6, range 1–120). Only 19% (38/200) of articles specified a single primary outcome. While all but two studies identified the number of participants in each intervention group, 117 (59%) failed to provide a measure of precision (confidence interval or standard error) for the difference in outcome between study arms. Sixty per cent of journals failed to meet the most basic CONSORT requirements in more than half of their articles (fig 2).

Discussion

As proponents of comprehensive data presentation, we believe that our stringent reporting measures are most relevant. Performance on these measures was dismal; less than 1% of available data was reported. We therefore focused on a lenient judging of the paper’s best reported primary outcome, but even by these generous criteria the presentation of a median 3.5% (interquartile range 3–6.5%) of the data cannot be considered adequate.

Limitations of study

We studied continuous outcomes in randomised trials published in a convenience sample of higher impact factor journals. Findings may not extend to other study designs and outcomes and to studies published in lower impact factor journals. We use a cardinal measure, percentage, to describe the comprehensiveness of reporting, but it can be argued that the elements being summed in the numerator—measures of central tendency, measure of variance, sample sizes, individual subject’s values—are not equivalent and that, for example, a mean has more information than one person’s value. This is a valid criticism and another way to look at these data is categorically, “Did the investigators show the distribution of the primary outcome?” With 17% of studies showing the distribution for the best outcome, and 9% of studies showing distributions for all primary outcomes, we believe that conclusions are unchanged.

Implications of results

What level of detail is appropriate for a scientific paper reporting the results of a clinical trial? At the low end of the spectrum are claims presented without supporting evidence (“Drug A is better than Drug B, take our word for it”). This level of reporting is inconsistent with the scientific method and is clearly inadequate. At the other extreme the entire dataset is made available to the scientific community. While there are compelling ethical and epistemological arguments for doing so,9 10 11 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 pragmatic and logistical concerns make authors reluctant to fully share their data.9 24 BMJ’s data sharing initiative has produced little shared data, and no author has posted data in response to Annals of Internal Medicine’s 2007 data sharing initiative (personal communication, Cynthia Mulrow).9 11

If full accessibility to all trial data is not yet feasible, what level of reporting should be required? Ziman offers one approach to defining an acceptable level: “The first priority of science is that meaningful messages should pass among scientists. Each message should not be so obscure or ambiguous that the recipient is unable either to give it whole-hearted assent or to offer well-founded objections.”25 He called this quality “consensibility” and argued that non-consensible communications stall the scientific process by burdening scientists with material that does not lead to clarification of a field’s important questions.25 While the amount of information required to achieve consensibility will vary from paper to paper and reader to reader, Ziman’s line of reasoning would suggest more information is better than less. Tufte shares this view for different reasons: “The deepest reason for displays that portray complexity and intricacy is that the worlds we seek to understand are complex and intricate.”26 Trial registration is one means of discouraging authors from presenting only those results that fit their argument; requiring that detailed information be presented is another.

Common arguments against the detailed presentation of trial results contend that it is unnecessary or it is unduly burdensome on authors, readers, or publishers. One form of the argument is that the detailed presentation of data is unnecessary because randomisation has eliminated the possibility of confounding. While this might be true for very large trials, the average number of subjects in the trials we studied was 118, a number far too small to ensure that randomisation produced groups at equivalent risk for the outcome. Consequently, critical readers will need to examine the relationships among potential confounding variables and the outcomes to satisfy themselves that confounding is not responsible for the results.

The concern that the presentation of detailed trial results is too much work for authors, that digestion of such results is too burdensome for reviewers and readers, and that production of these results is too much work for publishers cannot be discounted in a world where Twitter messages of ≤140 characters are a predominant mode of communication. We believe, however, that, through carefully constructed graphics, one can create the best of both worlds—images that convey both detailed information and summaries of the results so that readers can use the graphics at the level they desire.26 27 28 29 Detailed graphics take up no more space than simple ones. Consequently, complete reporting of the primary outcome should not require additional tables, figures, or text. Complete reporting in its fullest sense would likely require additional graphics, but, fortunately, desktop publishing has made the creation and printing of such graphics no more costly than producing text, and the internet provides a fiscally feasible method for providing supplementary information.

While the logistical barriers that resulted in incomplete reporting becoming the dominant presentation style no longer exist, some journals maintain stringent limits on the number of tables and figures that can be included in a manuscript; limits that make complete reporting difficult. However, increasing numbers of journals are allowing web-only supplements, suggesting that logistical impediments to complete reporting are diminishing.30 The BMJ, recognising that different readers have different information needs, now produces several versions of an article, including the pico summary, each geared towards readers with different information requirements.31

The print and supplementary figures in this paper are our attempt to practise what we preach. Each represents not only a complete dataset (200 data points), but also includes summary measures. The graph types we selected were intentional—many commonly used figure types (such as bar or line graphs) do not report high percentages of data (fig 2 and extra figs E and F in appendix 3 on bmj.com), whereas dot plots, scatterplots, and table-figure hybrids convey substantially more information in the same amount of space. Moreover, the inclusion of summary measures allows the casual reader to make a quick perusal while inviting others to look more fully at the data. Our results agree with other studies that suggest that there is much work to be done in educating authors about the principles of data presentation.32 33 34 35

The CONSORT statement, which provides guidance on the reporting of randomised trials, has been adopted by most major journals, yet only 45% of the papers we examined complied with CONSORT’s recommendations regarding the presentation of trial results (fig 2). Our study cannot discern whether differences among journals are due to differences in what is submitted or differences in editorial processes, although our analysis of the 20 papers from BMJ and Annals of Emergency Medicine suggests that the journal must play an active role in ensuring complete reporting. The current (2010) version of CONSORT requires that authors show “the results for each group for each primary and secondary outcome, the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval).”36 It makes no suggestion that authors use distributions to depict each subject’s outcome when that outcome is a continuous. The addition of such an item to CONSORT would stimulate authors to learn more about the effective use of graphics for the presentation of data, and, by doing so, decrease the potential for incomplete reporting bias.

Conclusions

Participants in randomised trials may be dismayed to learn that only a tiny fraction of the data collected in a trial is presented in the trial’s report. Figures seem to the best way to achieve comprehensive reporting, but many of the figures were in formats too simple (such as bar graphs) to convey distributions effectively. Reporting guidelines and more active journal editing of the graphical content of manuscripts may be required to improve the comprehensiveness of reporting.

What is already known on this topic

Clinical research papers present a highly selected subset of the available data

The full dataset is rarely made available to the journal’s readers

What this study adds

This study confirms that, on average, only a small fraction (<5%) of the available data is presented in randomised trials with continuous primary outcomes

Papers that use scatterplots and other graphic formats with high data density show the most data

Until such time when the posting of trial datasets becomes routine, journal editors should encourage authors to use figures to show their data, thereby reducing the possibility of incomplete reporting bias

Contributors: DLS and DGA developed the research question and designed the study. DFS did most of the data abstraction with help from DLS. All authors participated in the data analysis; DLS created the graphics and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with all authors involved in editing the final manuscript.

Funding: DLS has an unrestricted grant from the Korein Foundation, which has no involvement in the selection or conduct of research projects. DGA receives general support from Cancer Research UK programme grant C5529.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. DGA is a methodology editor for BMJ and DLS is a methodology and deputy editor for Annals of Emergency Medicine.

Data sharing: Our data are available upon request.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e8486

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: Scoring rules for measuring completeness of reporting

Appendix 2: Example of annotated article used in study

References

- 1.Broad W, Wade N. Betrayers of the truth. Oxford University Press, 1982.

- 2.Dickersin K, Min YI. Publication bias: the problem that won’t go away. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993;703:135-46. PMID: 8192291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ioannidis JP. Effect of the statistical significance of results on the time to completion and publication of randomized efficacy trials. JAMA 1998;279:281-6. PMID: 9450711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan A-W, et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e3081. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutton JL, Williamson PR. Bias in meta-analysis due to outcome variable selection within studies. Appl Stat 2000;49:359-70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dwan K, Altman DG, Cresswell L, Blundell M, Gamble CL, Williamson PR. Comparison of protocols and registry entries to published reports for randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;1:MR000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smyth RMD, Kirkham JJ, Jacoby A, Altman DG, Gamble C, Williamson PR. Frequency and reasons for outcome reporting bias in clinical trials: interviews with trialists. BMJ 2011;342:c7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeAngelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1250-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groves T. Managing UK research data for future use. BMJ 2009;338:b1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groves T. The wider concept of data sharing: view from the BMJ. Biostatistics 2010;11:391-2. 10.1093/biostatistics/kxq031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laine C, Goodman SN, Griswold ME, Sox HC. Reproducible research: moving toward research the public can really trust. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:450-3. PMID:17339612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schriger DL, Sinha R, Schroter S, Liu PY, Altman DG: From submission to publication: a retrospective review of the tables and figures in a cohort of randomized controlled trials. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:750-6, e1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper RJ, Schriger DL, Close RJ. Graphical literacy: the quality of graphs in a large-circulation journal. Ann Emerg Med 2002;40:317-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT Group. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:657-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:663-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delamothe T. Whose data are they anyway? BMJ 1996;312:1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vickers AJ. Whose data set is it anyway? Sharing raw data from randomized trials. Trials 2006;7:15. PMID: 16704733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gøtzsche PC. Why we need easy access to all data from all clinical trials and how to accomplish it. Trials 2011;12:249. 10.1186/1745-6215-12-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan A-W, Hróbjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA 2004;291:2457-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 2008. www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html.

- 22.Wendler D, Krohmal B, Emanuel EJ, Grady C, ESPRIT Group. Why patients continue to participate in clinical research. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royal Society. Science as an open enterprise. Royal Society Science Policy Centre, 2012. http://royalsociety.org/uploadedFiles/Royal_Society_Content/policy/projects/sape/2012-06-20-SAOE.pdf.

- 24.Hrynaszkiewicz I, Norton ML, Vickers AJ, Altman DG. Preparing raw clinical data for publication: guidance for journal editors, authors, and peer reviewers. Trials 2010;11:9. 10.1186/1745-6215-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziman JM. Reliable knowledge: an exploration of the grounds for belief in science. Cambridge University Press, 1978:6-7.

- 26.Tufte ER. Envisioning information. Graphics Press, 1990: 51.

- 27.Tufte ER. The visual display of quantitative information. Graphics Press, 1983.

- 28.Schriger DL, Cooper RJ. Achieving graphical excellence: suggestions and methods for creating high quality visual displays of experimental data. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:75-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen EA, Erhardt EB, Calhoun VD. Data visualization in the neurosciences: overcoming the curse of dimensionality. Neuron 2012;74:603-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schriger DL, Chehrazi AC, Merchant RM, Altman DG. Use of the internet by print medical journals in 2003 to 2009: a longitudinal observational study. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:153-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groves T. Innovations in publishing BMJ research. BMJ 2008;337:a3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pocock SJ, Travison TG, Wruck LM. Figures in clinical trial reports: current practice and scope for improvement. Trials 2007;8:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gelman A, Pasarica C, Dodhia R. Let’s practice what we preach: turning tables into graphs. Am Stat 2002;56:121-30. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drummond GB, Vowler SL. Show the data, don’t conceal them. J Physiol 2011;589(Pt 8):1861-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schriger DL, Altman DG, Vetter JA, Heafner T, Moher D. Forest plots in reports of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study reviewing current practice. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, for the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:726-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Scoring rules for measuring completeness of reporting

Appendix 2: Example of annotated article used in study